Abstract Expressionism 1 Abstract Expressionism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barnett Newman's

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Art and Art History Faculty Research Art and Art History Department 2013 Barnett ewN man's “Sense of Space”: A Noncontextualist Account of Its Perception and Meaning Michael Schreyach Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/art_faculty Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Repository Citation Schreyach, M. (2013). Barnett eN wman's “Sense of Space”: A Noncontextualist Account of Its Perception and Meaning. Common Knowledge, 19(2), 351-379. doi:10.1215/0961754X-2073367 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art and Art History Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art and Art History Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES BARNETT NEWMAN’S “SENSE OF SPACE” A Noncontextualist Account of Its Perception and Meaning Michael Schreyach Dorothy Seckler: How would you define your sense of space? Barnett Newman: . Is space where the orifices are in the faces of people talking to each other, or is it not [also] between the glance of their eyes as they respond to each other? Anyone standing in front of my paint- ings must feel the vertical domelike vaults encompass him [in order] to awaken an awareness of his being alive in the sensation of complete space. This is the opposite of creating an environment. This is the only real sensation of space.1 Some of the titles that Barnett Newman gave to his paintings are deceptively sim- ple: Here and Now, Right Here, Not There — Here. -

Patel Spring 2017 GL ARH 4470 Syllabus

Do not copy without the express written consent of the instructor. Syllabus Spring 2017 ARH 4470/ARH 5482 Contemporary Art A Discipline-Specific Global Learning Course1 Tuesday and Thursday 2-3:15pm Green Library, Room 165 Instructor: Dr. Alpesh Kantilal Patel Assistant Professor, Contemporary Art and Theory Director, MFA in Visual Arts Affiliate Faculty, Center for Women’s and Gender Studies Affiliate Faculty, African and African diaspora Program Contact information for instructor: Department of Art + Art History MM Campus, VH 235 Preferred mode of contact: [email protected] Office hours: Thursday: 12:45-1:45pm Course description: This course examines major artists, artworks, and movements after World War II; as well as broader visual culture—everything from music videos and print advertisements to propaganda and photojournalism—especially as the difference between ‘art’ and non-art increasingly becomes blurred and the objectivity of aesthetics is called into question. Movements studied include Abstract Expressionism, Pop, and Minimalism in the 1950s and 1960s; Post-Minimalism/Process Art, and Land art in the late 1960s and 1970s; Pastiche/Appropriation and rise of interest in “identity” in the 1980s; and the emergence of Post-Identity, Relational Art, Internet/New Media art, and Post- Internet art in the 1990s/post-2000 period. This course will explore the expansion of the art world beyond “Euro- America.” In particular, we will consider the shift from an emphasis on the international to transnational. We will focus not only on artistic production in the US, but also that in Europe, South and East Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. -

Teaching Strategies: How to Explain the History and Themes of Abstract Expressionism to High School Students Using the Integrative Model

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Honors Theses Undergraduate Research 2014 Teaching Strategies: How to Explain the History and Themes of Abstract Expressionism to High School Students Using the Integrative Model Kirk Maynard Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/honors Part of the Art and Design Commons Recommended Citation Maynard, Kirk, "Teaching Strategies: How to Explain the History and Themes of Abstract Expressionism to High School Students Using the Integrative Model" (2014). Honors Theses. 92. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/honors/92 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. 2014 Kirk Maynard HONS 497 [TEACHING STRATEGIES: HOW TO EXPLAIN THE HISTORY AND THEMES OF ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONISM TO HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS USING THE INTEGRATIVE MODEL] Abstract: The purpose of my thesis is to create a guideline for teachers to explain art history to students in an efficient way without many blueprints and precedence to guide them. I have chosen to focus my topic on Abstract Expressionism and the model that I will be using to present the concept of Abstract Expressionism will be the integrated model instructional strategy. -

ADOLPH GOTTLIEB (New York, 1903 – New York, 1974)

ADOLPH GOTTLIEB (New York, 1903 – New York, 1974) I use color in terms of emotional quality, as a vehicle for feeling... feeling is everything I have experienced or thought. Adolph Gottlieb was a prominent American painter and member of the first generation of Abstract Expressionists. Characterized by an idiosyncratic use of abstraction that utilized pictographs, tribal and mythological symbols and with a Surrealism influence. He was born in New York in 1903. He studied at public schools but at the age of 17 he left high school to travel around Europe and decided to be an artist. Gottlieb lived in Paris for six months where he visited The Louvre Museum daily and went to drawing classes at the Academie de la Grande Adolph Gotlieb, 1953 © Arnold Newman Chaumiere. He also spent another year visiting museums and galleries in Berlin, Munich, Vienna, Prague and Dresden, among other major European cities. He returned to New York in 1924. Gottlieb studied at The Art Students League, Parson School of Design, Educational Alliance and other local schools where he met his friends Barnet Newman, both shared a studio, Mark Rothko, John Graham, Milton Avery and Chaim Gross. He began producing works influenced by the stylized figuration of Milton Avery. Interested in Surrealism, Gottlieb’s art became more abstract with the incorporation of ideas as the automatic drawing. He was a founding member of some artists’ groups: “The Ten” (1935), the Federation of American Painters and Sculptors (1939) and New York Artist-Painters (1943). In 1951 Gottlieb is one of the main organizers of the protest that, would give him and his colleagues, the name of "The Irascibles". -

Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU 18th Annual Africana Studies Student Research Africana Studies Student Research Conference Conference and Luncheon Feb 12th, 1:30 PM - 2:45 PM Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art Shelby Miller Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons Miller, Shelby, "Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art" (2017). Africana Studies Student Research Conference. 1. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf/2016/004/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Events at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies Student Research Conference by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Shelby Miller Theories of Space and Place in Abstract Caribbean Art Bibliographic Style: MLA 1 How does one define the concepts of space and place and further translate those theories to the Caribbean region? Through abstract modes of representation, artists from these islands can shed light on these concepts in their work. Involute theories can be discussed in order to illuminate the larger Caribbean space and all of its components in abstract art. The trialectics of space theory deals with three important factors that include the physical, cognitive, and experienced space. All three of these aspects can be displayed in abstract artwork from this region. By analyzing this theory, one can understand why Caribbean artists reverted to the abstract style—as a means of resisting the cultural establishments of the West. To begin, it is important to differentiate the concepts of space and place from the other. -

Art in 1960S

Abstract Expressionism 1940s-1960s A form of abstract art that emphasized spontaneous, intuitive creation of unstructured expressions of the artist’s unconscious Action Painting: emphasized the dynamic handling of paint and techniques that were partly dictated by chance. The act of painting was as significant as the finished work: Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning Jackson Pollock, Blue Poles, 1952 William de Kooning, Untitled, 1975 Color-Field Painting: used large, soft-edged fields of flat color: Mark Rothko, Ab Reinhardt Mark Rothko, Lot 24, “No. 15,” 1952 “A square (neutral, shapeless) canvas, five feet wide, five feet high…a pure, abstract, non- objective, timeless, spaceless, changeless, relationless, disinterested painting -- an object that is self conscious (no unconsciousness), ideal, transcendent, aware of no thing but art (absolutely no anti-art). Ad Reinhardt, Abstract Painting,1963 –Ad Reinhardt Minimalism 1960s rejected emotion of action painters sought escape from subjective experience downplayed spiritual or psychological aspects of art focused on materiality of art object used reductive forms and hard edges to limit interpretation tried to create neutral art-as-art Frank Stella rejected any meaning apart from the surface of the painting, what he called the “reality effect.” Frank Stella, Sunset Beach, Sketch, 1967 Frank Stella, Marrakech, 1964 “What you see is what you see” -- Frank Stella Postminimalism Some artists who extended or reacted against minimalism: used “poor” materials such felt or latex emphasized process and concept rather than product relied on chance created art that seemed formless used gravity to shape art created works that invaded surroundings Robert Morris, Felt, 1967 Richard Serra, Cutting Device: Base Plat Measure, 1969 Hang Up (1966) “It was the first time my idea of absurdity or extreme feeling came through. -

Abstraction in 1936: Barr's Diagrams

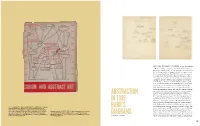

ALMOST SINCE THE MOMENT OF ITS FOUNDING, in 1929, The Museum of Modern Art has been committed to the idea that abstraction was an inherent and crucial part of the development of modern art. In fact the 1936 exhibition Cubism and Abstract Art, organized by the Museum’s founding director, Alfred H. Barr, Jr., made this argument its central thesis. In an attempt to map how abstraction came to be so important in modern art, Barr created a now famous diagram charting the history of Cubism’s and abstraction’s development from the 1890s to the 1930s, from the influence of Japanese prints to the aftermath of Cubism and Constructivism. Barr’s chart, which was published on the dust jacket of the exhibition’s catalogue (plate 452), began in an early version as a simple outline of the key factors affecting early modern art, and of the development of Cubism in particular, but over successive iterations became increasingly complex in its overlapping and intersecting lines of influence ABSTRACTION 1 (plates 453–58). The chart has two principal axes: on the vertical, time, and on the horizontal, styles or movements, with both lead- ing inexorably to the creation of abstract art. Key non-Western IN 1936: influences, such as “Japanese Prints,” “Near-Eastern Art,” and “Negro Sculpture,” are indicated by a red box. “Machine Esthetic” is also highlighted by a red box, and “Modern Architecture,” by 452. The catalogue for Cubism and Abstract Art, an exhibition at the Museum BARR’S which Barr meant the International Style, by a black box. -

Emuseum of Modernart, 11 West 53 Street, Newyork, N, Y

..~ Museum of Modern Art No.4; 53 Street, NewYork, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5·8900 Cable, Modernart FOR RELEASE: Tuesday, May 11, 1965 PRESS PREVIEW: Monday,Mey 10, 1965 11 a.m, - 4 p.m. ICANCOLLAGES,anexhibition from The Museumof Modern Art's special program of traveling exhibitions, will interrupt its current tour end be shCMnat the Museum from May11 through July 25. Twice as manyexhibitions are circulated in the United States and Canada by the Museum'SDapartment of Circulating Exhibitions as are shown yearly at the Museum in NewYork. Last year the exhibitions "lere seen in 139 com- MoMAExh_0766_MasterChecklist munities. The same department, in charge of the Kuseum's foreign program of Circu- lating Exhibitions sponsored by the International Council of the Museum, has prepared 75 exhibitions secu in 65 countries. I The<lOrksin the collage sbow, dating from 1950 to the present, deal with a I i The term I mediumwhich has grown in importance only during the last fifty years. "collage," from the French for pasting or paper-hanging, has been broad ly interpreted I as a technique of cutting and pasting various materials which are aometimes combined with drawing, watercoloor or oil. The exhibition includes the work of someof the foremost makers of collage in I li I this country __ Robert Motherwell, Esteban Vicente, Conred Marca-Rel and Joseph Cornell _ as well as other artists who have broadened the medium. Kynaston McShine, whodirected the exhibition, writes, "[Collage] has been a means of creative liberation, leading us to recogGize not only the beauty of ephemera but also that of texture and spatial effects different from those of painting and sculpture. -

CUBISM and ABSTRACTION Background

015_Cubism_Abstraction.doc READINGS: CUBISM AND ABSTRACTION Background: Apollinaire, On Painting Apollinaire, Various Poems Background: Magdalena Dabrowski, "Kandinsky: Compositions" Kandinsky, Concerning the Spiritual in Art Background: Serial Music Background: Eugen Weber, CUBISM, Movements, Currents, Trends, p. 254. As part of the great campaign to break through to reality and express essentials, Paul Cezanne had developed a technique of painting in almost geometrical terms and concluded that the painter "must see in nature the cylinder, the sphere, the cone:" At the same time, the influence of African sculpture on a group of young painters and poets living in Montmartre - Picasso, Braque, Max Jacob, Apollinaire, Derain, and Andre Salmon - suggested the possibilities of simplification or schematization as a means of pointing out essential features at the expense of insignificant ones. Both Cezanne and the Africans indicated the possibility of abstracting certain qualities of the subject, using lines and planes for the purpose of emphasis. But if a subject could be analyzed into a series of significant features, it became possible (and this was the great discovery of Cubist painters) to leave the laws of perspective behind and rearrange these features in order to gain a fuller, more thorough, view of the subject. The painter could view the subject from all sides and attempt to present its various aspects all at the same time, just as they existed-simultaneously. We have here an attempt to capture yet another aspect of reality by fusing time and space in their representation as they are fused in life, but since the medium is still flat the Cubists introduced what they called a new dimension-movement. -

A Finding Aid to the Anne Ryan Papers, Circa 1905-1970, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Anne Ryan papers, circa 1905-1970, in the Archives of American Art Rihoko Ueno 2018/01/25 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Biographical Material, circa 1920-circa 1970............................................ 4 Series 2: Correspondence, circa 1922-1968............................................................ 5 Series 3: Diaries and Journals, 1924-1942.............................................................. 7 Series 4: Writings, circa 1923-circa 1954............................................................... -

An Examination of an Analogic-Metaphoric Approach to Museum Education and Art Appreciation

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1983 An examination of an analogic-metaphoric approach to museum education and art appreciation. Marilyn JS Goodman University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Goodman, Marilyn JS, "An examination of an analogic-metaphoric approach to museum education and art appreciation." (1983). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 3879. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/3879 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UMASS/AMHERST 31EDbbQ1353Tt)t)4 AN EXAMINATION OF AN ANALOGIC- METAPHORIC APPROACH TO MUSEUM EDUCATION AND ART APPRECIATION A Dissertation Presented By MARILYN JS GOODMAN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION February 1983 Education Marilyn JS Goodman 1983 All Rights Reserved AN EXAMINATION OF AN ANALOGIC- METAPHORIC APPROACH TO MUSEUM EDUCATION AND ART APPRECIATION A Dissertation Presented By MARILYN JS GOODMAN Approved as to style and content by: 7f"i / 1 J Richard D. Konicek, Chairperson of Committee Liane Brandon, Member Ms Charles S. Chetham, Member Mario D. Fantini, Dean 9 School of Education iii DEDICATION To my mother, who, when I was seven years old, took me to the Museum of Modern Art and asked me how I felt about the paintings. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College Of

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture CUT AND PASTE ABSTRACTION: POLITICS, FORM, AND IDENTITY IN ABSTRACT EXPRESSIONIST COLLAGE A Dissertation in Art History by Daniel Louis Haxall © 2009 Daniel Louis Haxall Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2009 The dissertation of Daniel Haxall has been reviewed and approved* by the following: Sarah K. Rich Associate Professor of Art History Dissertation Advisor Chair of Committee Leo G. Mazow Curator of American Art, Palmer Museum of Art Affiliate Associate Professor of Art History Joyce Henri Robinson Curator, Palmer Museum of Art Affiliate Associate Professor of Art History Adam Rome Associate Professor of History Craig Zabel Associate Professor of Art History Head of the Department of Art History * Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii ABSTRACT In 1943, Peggy Guggenheim‘s Art of This Century gallery staged the first large-scale exhibition of collage in the United States. This show was notable for acquainting the New York School with the medium as its artists would go on to embrace collage, creating objects that ranged from small compositions of handmade paper to mural-sized works of torn and reassembled canvas. Despite the significance of this development, art historians consistently overlook collage during the era of Abstract Expressionism. This project examines four artists who based significant portions of their oeuvre on papier collé during this period (i.e. the late 1940s and early 1950s): Lee Krasner, Robert Motherwell, Anne Ryan, and Esteban Vicente. Working primarily with fine art materials in an abstract manner, these artists challenged many of the characteristics that supposedly typified collage: its appropriative tactics, disjointed aesthetics, and abandonment of ―high‖ culture.