The Search for the Kidnapped Children of Argentina's Disappeared

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mothers and Grandmothers of Plaza De Mayo and Influences on International Recognition of Human Rights Organizations in Latin America

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ETD - Electronic Theses & Dissertations The Mothers and Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo and Influences on International Recognition of Human Rights Organizations in Latin America By Catherine Paige Southworth Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Latin American Studies December 15, 2018 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: W. Frank Robinson, Ph.D. Marshall Eakin, Ph.D. To my parents, Jay and Nancy, for their endless love and support ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I must express my appreciation and gratitude to the Grandmoth- ers of the Plaza de Mayo. These women were so welcoming during my undergraduate in- ternship experience and their willingness to share their stories will always be appreciated it. My time with the organization was fundamental to my development as a person as an aca- demic. This work would not have been possible without them. I am grateful everyone in the Center for Latin American Studies, who have all sup- ported me greatly throughout my wonderful five years at Vanderbilt. In particular, I would like to thank Frank Robinson, who not only guided me throughout this project but also helped inspire me to pursue this field of study beginning my freshman year. To Marshall Eakin, thank you for all of your insights and support. Additionally, a thank you to Nicolette Kostiw, who helped advise me throughout my time at Vanderbilt. Lastly, I would like to thank my parents, who have supported me unconditionally as I continue to pursue my dreams. -

Transfiguraciones Urbanas Y Arquitectónicas De La Avenida Rio Branco En Rio De Janeiro Y De La Avenida De Mayo En Buenos Aires En El Siglo XX

CCIA’2008 1 Transfiguraciones urbanas y arquitectónicas de la Avenida Rio Branco en Rio de Janeiro y de la Avenida de Mayo en Buenos Aires en el siglo XX. José Kós, Roberto Segre, Erivelton Muniz, Maria Laura Rosenbusch, Nathália Alcantara Abstract. It was developed a deep research on the two main sociales de las nacientes burguesías locales, que eran avenues built at the beginning of 20th Century in Buenos Aires asumidos del modelo haussmaniano francés. El lema “París en and Rio de Janeiro, as an expression of the urban symbolism América”, constituía el objetivo de la sustitución de la needed by the local bourgeoisie, against the traditional colonial subdesarrollada ciudad colonial, para crear las bases de la image of architecture and urbanism. Avenida de Mayo started at modernidad del siglo XX; y fue aplicado en la mayoría de las the end of 19th Century in Buenos Aires and inspired Avenida Central (now Rio Branco Avenue) in Rio de Janeiro, built in the ciudades capitales de la región: México DF; La Habana, first decade of 20th Century. Even the functional purpose and Santiago de Chile, Montevideo, Caracas, entre otras. No se the aesthetic particularities of buildings are similar – under the trataba solamente de un cambio estético ni de escala – las French influence – but there are strong differences that lead to apretadas calles coloniales eran inservibles para el tránsito de the perdurability of Avenida de Mayo and the loss of its original vehículos a motor, que ya comenzaban a difundirse en characteristics in Rio Branco Avenue from the Thirties on. In América Latina –, sino también de albergar las nuevas this work, with the help of various programs –MySql and Adobe funciones administrativas, comerciales, políticas y recreativas, Flash CS3 combined with 3D Papervision and PHP – it will be adecuadas a las demandas de una población urbana en possible for users to learn about the evolution and constante crecimiento. -

Jaque103.Pdf

ara el buen funcionamiento de un equipo de aire acondicionado, hace falta algo más que elegir bien la marca. En Centro Eléctrico disponemos de un Departamento Especializado, que no sólo lo asesorará gratuitamente, sino que le brindará desde el punto de vista técnico, cual es la solución más adecuada para sus necesidades, sean domésticas o comerciales. Un buen asesoramiento técnico que incluya correcto balance térmico y potencia (en toda la gama de BTU) o número de aparatos necesarios, hará que la optimización de resultados no sólo se refleje en el_ rendimiento de su aparato, sino también de su economía. El Aire Acondicionado no es un gasto, es una inversión que Ud. puede disfrutarla todo el año. En Montevideo 8 sucursales y Montevideo Shopping Center, y 28 sucursales en el interior del país. ctor DIRECTOR: Al Felipe Flores Silva REDACTOR RESPONSABLE: Enrique Alonso Fernández (25 de Mayo esq. Independencia, Pando). posiciones públicas rechazo a un modo de pública y sondea en los EDITOR: del pasado fin de conducción que ca MarcoMaggi icie mb re fenómenos culturales pro mete ser semana en las que Wil lificaron como "pre más significativos. tan agita.do son Ferreira Aldunate potente y so beroio ". Hechos, personas, SE'CRETARIO DE REDACCION: como los recordó un año de su El episodio es sucesos que también Enrique Alonso Fernández mesesque lo pre- liberación y el Partido muy importante y_ son noticia y que con NACIONALES: Información y Report<:jes: Emiliano cedieron. Sobre los Colorado, un año de sobre él informamos tribuyen a trazar el per cotelo,,Luis Rico, José·Marii'lo. -

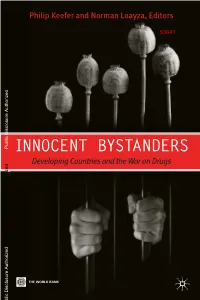

Drug Prohibition and Developing Countries: Uncertain Benefi Ts, Certain Costs 9 Philip Keefer, Norman Loayza, and Rodrigo R

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized INNOCENT BYSTANDERS INNOCENT Philip Keefer and Norman Loayza, Editors andNormanLoayza, Philip Keefer Developing Countries and the War onDrugs War Countriesandthe Developing INNOCENT BYSTANDERS INNOCENT BYSTANDERS Developing Countries and the War on Drugs PHILIP KEEFER AND NORMAN LOAYZA Editors A COPUBLICATION OF PALGRAVE MACMILLAN AND THE WORLD BANK © 2010 The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved 1 2 3 4 13 12 11 10 A copublication of The World Bank and Palgrave Macmillan. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the United Kingdom is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the United States is a division of St. Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe, and other countries. This volume is a product of the staff of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. The fi ndings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this volume do not nec- essarily refl ect World Bank policy or the views of the Executive Directors of The World Bank or the governments they represent. The publication of this volume should not be construed as an endorse- ment by The World Bank of any arguments, either for or against, the legalization of drugs. -

Episcopalciiuriimen

EPISCOPALCIIURIIMEN soUru VAFR[CA Room 1005 * 853 Broadway, New York, N . Y. 10003 • Phone : (212) 477-0066 , —For A free Southern Afilcu ' May 1982 MISSIONS MOVEMENTS NAMIBIA 'The U .S. 'overnment has become an agent in South Africa's "holy crusade" against Communism . ' - The Rev Dr Albertus Maasdorp, general secretary of the Council of Churches in Namibia, THE NEW YORK TIMES, 25 April 1982. It was a . mission of frustration and a harsh learning experience . Four Namibian churchmen made a month-long visit to Western nations to express their feelings about the unending, agonizing occupation of their country by the South African regime and the fruitless talks on a Namibian settlement which the .Western Contact Group - the USA, Britain, France ,West Germany and Canada - has staged for five long years . Anglican Bishop James Kauluma, presi- dent of the Council of Churches in Namibia ; Bishop Kleopas Du neni of the Evangelical Luth- eran Ovambokavango Church ; Pastor Albertus Maasdorp, general secretary of the CCN ;, and the, assistant to Bishop D,mmeni, Pastor Absalom Hasheela, were accompanied by a representative of the South African Council of Churches and the general secretary of the All Africa Coun- cil of Oburches which sponsored the trip . They visited France, Sweden, Britain and Canada, end terminated their journey in the United States . It was here that the Namibian pilgrims encountered the steely disregard for Namibian aspirations by functionaries of a major power mapped up in its geopolitical stratagems. They met with Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Chester .Crocker, whose time is primarily devoted to pursuing the mirage of a Pretorian agreement to the United Nations settlement plan for Namibia . -

Argentina-And-South-Africa.Pdf

1 2 Argentina and South Africa facing the challenges of the XXI Century Brazil as the mirror image 3 4 Argentina and South Africa facing the challenges of the XXI Century Brazil as the mirror image Gladys Lechini 5 Lechini, Gladys Argentina and South Africa facing the challenges of the XXI Century: Brazil as the mirror image. 1a ed. Rosario: UNR Editora. Editorial de la Universidad Nacional de Rosario, 2011. 300 p. ; 23x16 cm. ISBN 978-950-673-920-1 1. Política Económica. I. Título CDD 320.6 Diseño de tapa y diseño interior UNR Editora ISBN 978-950-673-920-1 © Gladys Lechini. 2011 IMPRESO EN LA ARGENTINA - PRINTED IN ARGENTINA UNR EDITORA - EDITORIAL DE LA UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE ROSARIO SECRETARÍA DE EXTENSIÓN UNIVERSITARIA 6 To my son and daughter, Ramiro and Jimena, for their patience and love To Edgardo, my companion along this journey, for his love, support and understanding To my parents, for creating a comfortable environment to be myself. 7 8 Contents Acknowledgements | 11 Prologue | 13 Dedicatory | 15 Introduction | 17 Chapter I An Approach to Argentine-African Relations (1960-2000) | 30 Chapter II From Policy Impulses to Policy Outlines (1960-1989) | 52 Chapter III The Politics of No-Policy (1989-1999) | 75 Chapter IV The Mirror Image: Brazil’s African Policy (1960-2000) | 105 Chapter V Argentina and South Africa: Dual Policy and Ambiguous Relations (1960-1983) | 140 Chapter VI Defining the South African Policy: the Alfonsín Administration (1983-1989) | 154 Chapter VII Menem and South Africa: between Presidential Protagonism -

A History of Political Murder in Latin America Clear of Conflict, Children Anywhere, and the Elderly—All These Have Been Its Victims

Chapter 1 Targets and Victims His dance of death was famous. In 1463, Bernt Notke painted a life-sized, thirty-meter-long “Totentanz” that snaked around the chapel walls of the Marienkirche in Lübeck, the picturesque port town outside Hamburg in northern Germany. Individuals covering the entire medieval social spec- trum were represented, ranging from the Pope, the Emperor and Empress, and a King, followed by (among others) a duke, an abbot, a nobleman, a merchant, a maiden, a peasant, and even an infant. All danced reluctantly with grinning images of the reaper in his inexorable procession. Today only photos remain. Allied bombers destroyed the church during World War II. If Notke were somehow transported to Latin America five hundred years later to produce a new version, he would find no less diverse a group to portray: a popular politician, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, shot down on a main thoroughfare in Bogotá; a churchman, Archbishop Oscar Romero, murdered while celebrating mass in San Salvador; a revolutionary, Che Guevara, sum- marily executed after his surrender to the Bolivian army; journalists Rodolfo Walsh and Irma Flaquer, disappeared in Argentina and Guatemala; an activ- ist lawyer and nun, Digna Ochoa, murdered in her office for defending human rights in Mexico; a soldier, General Carlos Prats, murdered in exile for standing up for democratic government in Chile; a pioneering human rights organizer, Azucena Villaflor, disappeared from in front of her home in Buenos Aires never to be seen again. They could all dance together, these and many other messengers of change cut down by this modern plague. -

Public Support for Democracy and the Rule of Law in the Southern Cone

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Winter 2018 Public Support for Democracy and the Rule of Law in the Southern Cone Patrick James Baga University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Baga, Patrick James, "Public Support for Democracy and the Rule of Law in the Southern Cone" (2018). Master's Theses and Capstones. 1228. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/1228 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PUBLIC SUPPORT FOR DEMOCRACY AND THE RULE OF LAW IN THE SOUTHERN CONE BY PATRICK J. BAGA Baccalaureate Degree (BA) in Political Science, University of New Hampshire, 2017 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Political Science December, 2018 i This thesis was examined and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Political Science by: Thesis Director, Mary Frances Malone, Associate Professor of Political Science Madhavi Divya Devasher, Assistant Professor of Political Science Jeannie Sowers, Associate Professor of Political Science On December 3, 2018 Approval signatures are on file with the University of New Hampshire Graduate School. ii Acknowledgements I have been fortunate throughout my life to have been surrounded by people who have encouraged me to pursue whatever it is that I wish to pursue. -

Argentina | Freedom House Page 1 of 5

Argentina | Freedom House Page 1 of 5 Argentina freedomhouse.org Popular support for President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner continued its decline in 2014, due primarily to inflation and insecurity. Officials devalued the peso by 19 percent in January in order to shore up international currency reserves (which fell to a seven-year low in 2014), prompting a surge in inflation. An estimated 24 to 30 percent annual inflation rate during the year eroded the purchasing power of Argentines and increased the incentive to buy black market dollars. Inflation rose in spite of the government’s price watch agreement—Precios Cuidados (“protected prices”)—which mandated reduced prices on more than 150 products sold in the largest supermarket chains. Argentina also struggled with declining public safety in 2014 as the country played an increasing role in the international drug trade. In April, a 24-hour general strike by labor unions brought large portions of the country to a standstill, affecting public transportation and government offices, and threatening the movement of the soybean harvest. Strikers demanded higher pay, lower taxes, and an increase in living standards amid the rising inflation. The Fernández administration attempted to meet the country’s persistent economic uncertainty with pragmatism. By agreeing to a $5 billion settlement, the government resolved a two-year dispute with Repsol, a Spanish company whose controlling stake in an Argentine oil firm had been nationalized in 2012. The national statistics agency made efforts to increase transparency by reporting more credible inflation data, and the government exercised fiscal restraint by cutting expensive and unsustainable water and natural gas subsidies. -

Weapons for Pensions 25 Was a Soviet Spy) on the Original 9/11 (1973)

Minns 1/9/04 1:35 AM Page 24 24 Weapons A Dedication To the people of Argentina whose pensions for helped pay for the so-called ‘odious’ debt1 Pensions used to buy British, French and US helicopters, which were then used to throw How social security their tortured children and friends into the became Atlantic and Pacific – the 30,000 national security ‘disappeared’ in Argentina, 9,000 in Chile, and countless others in neighbouring countries. This especially includes Jewish Richard Minns citizens under Argentinian and Chilean governments, which welcomed ex-Nazis planning the Third World War – against communism (Goni, 2003; Mount, 2002). Jewish deaths were over-represented in the final toll of ‘the disappeared’, while Israel supplied weapons (Rein, 2003). The US Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger, condoned these crimes against humanity in the battle against alleged communism and dissidence (The Guardian, December 12, 2003, ‘Kissinger Approved Argentinian Dirty War’) and helped to supply the weapons by various means. The UK Labour governments, under Harold Wilson and James Callaghan, prior to that Conservative Edward Heath, and latterly Margaret Thatcher, and the labour movement were variously preoccupied with three-day weeks, public sector strikes and confrontation with trade unions. Like Israel and its supply of weapons which killed Jews, the weapons flowed to dictatorships Richard Minns is an where trade unionists were being killed. independent researcher The US Central Intelligence Agency based in Buenos Aires and orchestrated a coup in Chile which brought London. He is the author Augusto Pinochet to power, and killed of The Cold War in (euphemistically called suicide) Welfare: Stock Markets democratically-elected Salvador Allende versus Pensions (Verso). -

Pensar La Dictadura: Terrorismo De Estado En Argentina Presidenta De La Nación Dra

Pensar la dictadura: terrorismo de Estado en Argentina Presidenta de la Nación Dra. Cristina Fernández de Kirchner Ministro de Educación de la Nación Prof. Alberto Sileoni Secretaria de Educación Prof. María Inés Abrile de Vollmer Subsecretaria de Equidad y Calidad Lic. Mara Brawer Pensar la dictadura: terrorismo de Estado en Argentina PEGUNTAS, RESPUESTAS Y PROPUESTAS PARA SU ENSEÑANZA. Coordinación Programa «Educación y Memoria» Federico Lorenz, María Celeste Adamoli Equipo Programa «Educación y Memoria» Matías Farías, Cecilia Flachsland, Pablo Luzuriaga, Violeta Rosemberg, Edgardo Vannucchi Revisión editorial Roberto Pittaluga Diseño y producción visual Juan Furlino Foto de tapa Gonzalo Martínez, Fototeca de ARGRA (Buenos Aires, 2004) Primera edición marzo de 2010 © 2010. Ministerio de Educación de la Nación Argentina. Impreso en Argentina. Publicación de distribución gratuita Prohibida su venta. Se permite la reproducción total o parcial de este libro con expresa mención de la fuente y autores. PENSAR LA DICTADURA: terrorismo de Estado en Argentina PEGUNTAS, RESPUESTAS Y PROPUESTAS PARA SU ENSEÑANZA. ÍNDICE Un fundamento para la esperanza Fuentes CAPÍTULO 2. Alberto Sileoni. Ministro de Educación 9 I. La voz de los responsables 36 DICTADURA Y SOCIEDAD II. Diálogo entre Jacobo Timerman y el Educar en Derechos Humanos represor Ramón Camps 39 9. La última dictadura, ¿tuvo apoyo Mara Brawer. Subsecretaría de Equidad y III. Carta Abierta de un escritor a la Junta social? 61 Calidad 11 Militar, por Rodolfo Walsh 40 10. ¿Cuál fue el rol de los trabajadores IV. La deuda externa 42 durante la última dictadura? 64 Programa Educación y Memoria 13 V. Memorias de una presa política 11. -

Argentina's Reparations Bonds: an Analysis of Continuing Obligations

Fordham International Law Journal Volume 28, Issue 3 2004 Article 9 Argentina’s Reparations Bonds: An Analysis of Continuing Obligations Christina M. Wilson∗ ∗ Copyright c 2004 by the authors. Fordham International Law Journal is produced by The Berke- ley Electronic Press (bepress). http://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ilj Argentina’s Reparations Bonds: An Analysis of Continuing Obligations Christina M. Wilson Abstract This Note will address the various avenues along which the reparation recipients might pur- sue the vindication of their right to reparations. Part I will provide background information on the Dirty War, reconciliation process, reparation laws and the economic events that resulted in Ar- gentina’s sovereign debt crisis. Part I will also describe the various sources of law both domestic and international upholding the right to reparations. Part II will explore the various cases that have interpreted this right and the implications they have on the reparation recipients’ possible reme- dies. Part III will analyze which of these remedies seems most likely to yield a favorable result for the reparation recipients. NOTES ARGENTINA'S REPARATION BONDS: AN ANALYSIS OF CONTINUING OBLIGATIONS ChristinaM. Wilson* INTRODUCTION Born in 1925, Elsa Oesterheld grew up an only child in Ar- gentina.1 She married a comic book scriptwriter and had four daughters who, in 1976, were all married and ranged in age from eighteen to twenty-three.2 Two of her daughters were pregnant and the other two had children.' Within months, they were all gone.4 The military abducted her husband, her four daughters, and two of her sons-in-law, leaving Elsa to raise her * Associate at Shearman & Sterling, LLP, New York, New York.