A Comparative Analysis of Ch'orti' Verbal Art and the Poetic Discourse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

With the Protection of the Gods: an Interpretation of the Protector Figure in Classic Maya Iconography

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography Tiffany M. Lindley University of Central Florida Part of the Anthropology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Lindley, Tiffany M., "With The Protection Of The Gods: An Interpretation Of The Protector Figure In Classic Maya Iconography" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2148. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2148 WITH THE PROTECTION OF THE GODS: AN INTERPRETATION OF THE PROTECTOR FIGURE IN CLASSIC MAYA ICONOGRAPHY by TIFFANY M. LINDLEY B.A. University of Alabama, 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Anthropology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2012 © 2012 Tiffany M. Lindley ii ABSTRACT Iconography encapsulates the cultural knowledge of a civilization. The ancient Maya of Mesoamerica utilized iconography to express ideological beliefs, as well as political events and histories. An ideology heavily based on the presence of an Otherworld is visible in elaborate Maya iconography. Motifs and themes can be manipulated to convey different meanings based on context. -

The Rulers of Palenque a Beginner’S Guide

The Rulers of Palenque A Beginner’s Guide By Joel Skidmore With illustrations by Merle Greene Robertson Citation: 2008 The Rulers of Palenque: A Beginner’s Guide. Third edition. Mesoweb: www. mesoweb.com/palenque/resources/rulers/PalenqueRulers-03.pdf. Publication history: The first edition of this work, in html format, was published in 2000. The second was published in 2007, when the revised edition of Martin and Grube’s Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens was still in press, and this third conforms to the final publica- tion (Martin and Grube 2008). To check for a more recent edition, see: www.mesoweb.com/palenque/resources/rulers/rulers.html. Copyright notice: All drawings by Merle Greene Robertson unless otherwise noted. Mesoweb Publications The Rulers of Palenque INTRODUCTION The unsung pioneer in the study of Palenque’s dynastic history is Heinrich Berlin, who in three seminal studies (Berlin 1959, 1965, 1968) provided the essential outline of the dynasty and explicitly identified the name glyphs and likely accession dates of the major Early and Late Classic rulers (Stuart 2005:148-149). More prominent and well deserved credit has gone to Linda Schele and Peter Mathews (1974), who summarized the rulers of Palenque’s Late Classic and gave them working names in Ch’ol Mayan (Stuart 2005:149). The present work is partly based on the transcript by Phil Wanyerka of a hieroglyphic workshop presented by Schele and Mathews at the 1993 Maya Meet- ings at Texas (Schele and Mathews 1993). Essential recourse has also been made to the insights and decipherments of David Stuart, who made his first Palenque Round Table presentation in 1978 at the age of twelve (Stuart 1979) and has recently advanced our understanding of Palenque and its rulers immeasurably (Stuart 2005). -

THE MYTH of ORPHEUS and EURYDICE in WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., Universi

THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN LITERATURE by MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A., University of Toronto, 1953 M.A., University of Toronto, 1957 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OP PHILOSOPHY in the Department of- Classics We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, i960 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada. ©he Pttttrerstt^ of ^riitsl} (Eolimtbta FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES PROGRAMME OF THE FINAL ORAL EXAMINATION FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of MARK OWEN LEE, C.S.B. B.A. University of Toronto, 1953 M.A. University of Toronto, 1957 S.T.B. University of Toronto, 1957 WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 21, 1960 AT 3:00 P.M. IN ROOM 256, BUCHANAN BUILDING COMMITTEE IN CHARGE DEAN G. M. SHRUM, Chairman M. F. MCGREGOR G. B. RIDDEHOUGH W. L. GRANT P. C. F. GUTHRIE C. W. J. ELIOT B. SAVERY G. W. MARQUIS A. E. BIRNEY External Examiner: T. G. ROSENMEYER University of Washington THE MYTH OF ORPHEUS AND EURYDICE IN WESTERN Myth sometimes evolves art-forms in which to express itself: LITERATURE Politian's Orfeo, a secular subject, which used music to tell its story, is seen to be the forerunner of the opera (Chapter IV); later, the ABSTRACT myth of Orpheus and Eurydice evolved the opera, in the works of the Florentine Camerata and Monteverdi, and served as the pattern This dissertion traces the course of the myth of Orpheus and for its reform, in Gluck (Chapter V). -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

A Multifaceted Nuptial Blessing: the Use of Ruth 4:11–12 Within Medieval Hebrew Epithalamia

A MULTIFACETED NUPTIAL BLESSING: THE USE OF RUTH 4:11–12 WITHIN MEDIEVAL HEBREW EPITHALAMIA Avi Shmidman* ABSTRACT: When bestowing poetic blessings upon newly married couples, the medieval Hebrew poets often advance analogies to biblical figures, indicating their wish that the couple should merit the good fortune of, for instance, the forefathers Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, or of later biblical figures such as Moses, Zipporah, Phinehas, or Hannah. The most common analogy offered, however, is that of the matriarchs Rachel and Leah, as per Boaz’s nuptial blessing from Ruth 4:11: “May the Lord make the woman who is coming into your house like Rachel and Leah, both of whom build up the House of Israel!” In this study, the usage of this recurring motif throughout medieval Hebrew epithalamia will be considered, so as to demonstrate its role as a focal point of poetic creativity. The medieval Hebrew poets composed hundreds of epithalamia, celebrating nuptial occasions within the Israelite nation, while offering blessings on behalf of the newly married couples.1 Many of these blessings center upon comparisons with biblical figures. For instance, ozrem uvarkhem ke’ish) עָזְרֵם ּובָרְכֵםּכְאִיׁש נִתְּבָרְֵךּבַּכֹל :one anonymous Palestinian poet writes nitbarekh bakkol, “assist them and bless them as he who was blessed in all things”),2 praying that the bride and groom should merit the blessings of Abraham. Similarly, the Palestinian * Lecturer in the Department of Literature of the Jewish People at Bar-Ilan University. Email: avi.shmidman@ biu.ac.il. I would like to thank my colleague Dr Tzvi Novick for his insightful comments on an earlier draft of this paper. -

Look Homeward, Angel"

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1994 The Problem of Time in Thomas Wolfe's "Look Homeward, Angel" Patrick M. Curran College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Curran, Patrick M., "The Problem of Time in Thomas Wolfe's "Look Homeward, Angel"" (1994). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625884. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-7tbv-bk17 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PROBLEM OF TIME IN THOMAS WOLFE'S LOOK HOMEWARD, ANGEL A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements of the Degree of Master of Arts by Patrick M. Curran, Jr. 1994 ProQuest Number: 10629309 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10629309 Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

Creation Cosmos

Creation, Cosmos, and the Imagery of Palenque and Copan Linda Schele and Khristaan D. Villela University of Texas, Austin At the 1992 Texas Meetings, Schele published in Schele (1992) and Freidel, (1992) presented a new interpretation of the Schele, and Parker (1993), we discuss here creation myth and the imagery associated only the main features of the story and its with it, as they are recorded in Classic Period association to astronomical phenomena. inscriptions. There is continuing debate The story of creation on Quirigua about some of the details in this reconstruc- Stela C (fig. 1) gives us the most detailed tion, but various researchers (Schele, Grube, information about the first moment. The text Nahm, R. Johnson, and Quenon) have tested describes the first event as the “appearance some of its patterns and found them to be or manifestation of an image” (halhi productive. This new reconstruction resulted k’ohba). Here the image that appeared was from the decipherment of texts at Quirigua, of three stone-settings (u tz’apwa tun), Palenque, and elsewhere, relating the events described as a jaguar throne stone placed by of creation and associating them with the Paddler Gods at a place called Na-Ho- various constellations, the Milky Way, and Chan, ‘House (or First or Female) Five- their movement through the sky. Since a Sky’; a snake throne stone set up by an detailed discussion of the creation story is unknown god at Kab-Kah,1 ‘Earth-town’; Fig. 1. The Creation Passage from Quirigua Stela C. 1 a. A council of gods aiding in the setting of the jaguar throne. -

Maya Hieroglyphic Writing

MAYA HIEROGLYPHIC WRITING Workbook for a Short Course on Maya Hieroglyphic Writing Second Edition, 201 1 J. Kathryn Josserandt and Nicholas A. Hopkins Jaguar Tours 3007 Windy Hill Lane Tallahassee, 32308-4025 FL (850) 385-4344 [email protected] This material is based on work supported in partby Ihe NationalScience Foundation (NSF) under grants BNS-8305806 and BNS-8520749, administered by Ihe Institute for Cultural Ecology of Ihe Tropics (lCEr), and by Ihe National Endowment for Ihe Humanities (NEH), grants RT-20643-86 and RT-21090-89. Any findingsand conclusions or recommendationsexpressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect Ihe views of NSF, NEH, or ICEr. Workbook © Jaguar Tours 2011 CONTENTS Contents Credits and Sources for Figures iv Introductionand Acknowledgements v Bibliography vi Figure 1-1. Mesoamerican Languages x Figure 1-2. The Maya Area xi Figure 1-3. Chronology Chart for tbe Maya Area xii P ART The Classic Maya Maya Hieroglypbic Writing 1: and Figure 14. A FamilyTree of Mayan Languages 2 Mayan Languages 3 Chronology 3 Maya and Earlier Writing 4 Context and Content S Tbe Writing System 5 Figure 1-5. Logographic Signs 6 Figure 1-6. Phonetic Signs 6 Figure 1-7. Landa's "Alphabet" 6 Figure 1-8. A Maya Syllabary 8 Figure 1-9. Reading Order witbin tbe Glyph Block 10 Figure 1-10. Reading Order of Glypb Blocks 10 HieroglyphicTexts II Word Order II Figure 1-11. Examples of Classic Syntax 12 Figure 1-12. Unmarked and Marked Word Order 12 Figure 1-13. Backgrounding and Foregrounding 12-B Figure 1-14. -

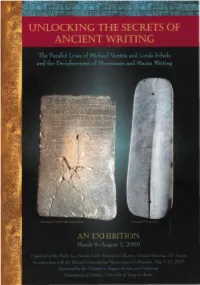

Unlocking the Secrets of Ancient Writing

Figure 1: Left Cover Photograph Linear B tablet, Pylos Tn 316 Mycenaean, Late Helladic III B, 1200 B.C.E. Clay, accidental ly fired H 7.8 in. x W 5.0 in. x D 0.9 in. National Archaeological Museum, Athens Photograph © PASP slide archives OLM) On the front side of Pylos T n 3 16, the famous 'human sacrifice' tablet, the scribe experimented with the layout for entering information about ceremonial offerings made by the community of Pylos (pu-ro in large characters twice at left) to sanctuaries in the palatial territory of Bronze Age Messenia. Note the ideographic characters for golden vases and for human beings. Entries continue on the verso. It is debated whether the MAN and WOMAN entries j,,-, ,/ ; / were 'sacrificial victims' or 'sacristans' bringing the vases. The lower \11 part of the rectosurface has graffiti, possibly the Linear B abc's or y:L iroha, written by the scribe in testing the readiness of the clay. Cf. ~-- - ---.'.._ )/ /11:v T.G. Palaima, "Kn02-Tn 316," in S. Deger-Jalkoczy eta!. eds., FloreantStudia Mycenaea(Vienna 1999) Band II, 437-461. Figure 2: Drawing of the front of tablet PYTn 316. Line drawing by Emmett L. Bennett, Jr. Figure3: Right Cover Photograph Jade celt, the Leiden Plaque Maya, Early Classic period, C.E. 320 . Incised jade = H 8.5 in. x W 3.4 in. x D 0.4 in. Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde, Leiden, Holland Photograph © Justin Kerr, K2909 This incised jade, once used as a royal belt ornament , carries an inscription on the versothat tells of the accession (the "seating") of a Maya ruler which occurred on September 17, C.E. -

Breaking the Maya Code : Michael D. Coe Interview (Night Fire Films)

BREAKING THE MAYA CODE Transcript of filmed interview Complete interview transcripts at www.nightfirefilms.org MICHAEL D. COE Interviewed April 6 and 7, 2005 at his home in New Haven, Connecticut In the 1950s archaeologist Michael Coe was one of the pioneering investigators of the Olmec Civilization. He later made major contributions to Maya epigraphy and iconography. In more recent years he has studied the Khmer civilization of Cambodia. He is the Charles J. MacCurdy Professor of Anthropology, Emeritus at Yale University, and Curator Emeritus of the Anthropology collection of Yale’s Peabody Museum of Natural History. He is the author of Breaking the Maya Code and numerous other books including The Maya Scribe and His World, The Maya and Angkor and the Khmer Civilization. In this interview he discusses: The nature of writing systems The origin of Maya writing The role of writing and scribes in Maya culture The status of Maya writing at the time of the Spanish conquest The impact for good and ill of Bishop Landa The persistence of scribal activity in the books of Chilam Balam and the Caste War Letters Early exploration in the Maya region and early publication of Maya texts The work of Constantine Rafinesque, Stephens and Catherwood, de Bourbourg, Ernst Förstemann, and Alfred Maudslay The Maya Corpus Project Cyrus Thomas Sylvanus Morley and the Carnegie Projects Eric Thompson Hermann Beyer Yuri Knorosov Tania Proskouriakoff His own early involvement with study of the Maya and the Olmec His personal relationship with Yuri -

Reassessing Shamanism and Animism in the Art and Archaeology of Ancient Mesoamerica

religions Article Reassessing Shamanism and Animism in the Art and Archaeology of Ancient Mesoamerica Eleanor Harrison-Buck 1,* and David A. Freidel 2 1 Department of Anthropology, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH 03824, USA 2 Department of Anthropology, Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63105, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Shamanism and animism have proven to be useful cross-cultural analytical tools for anthropology, particularly in religious studies. However, both concepts root in reductionist, social evolutionary theory and have been criticized for their vague and homogenizing rubric, an overly romanticized idealism, and the tendency to ‘other’ nonwestern peoples as ahistorical, apolitical, and irrational. The alternative has been a largely secular view of religion, favoring materialist processes of rationalization and “disenchantment.” Like any cross-cultural frame of reference, such terms are only informative when explicitly defined in local contexts using specific case studies. Here, we consider shamanism and animism in terms of ethnographic and archaeological evidence from Mesoamerica. We trace the intellectual history of these concepts and reassess shamanism and animism from a relational or ontological perspective, concluding that these terms are best understood as distinct ways of knowing the world and acquiring knowledge. We examine specific archaeological examples of masked spirit impersonations, as well as mirrors and other reflective materials used in divination. We consider not only the productive and affective energies of these enchanted materials, but also the Citation: Harrison-Buck, Eleanor, potentially dangerous, negative, or contested aspects of vital matter wielded in divinatory practices. and David A. Freidel. 2021. Reassessing Shamanism and Keywords: Mesoamerica; art and archaeology; shamanism; animism; Indigenous ontology; relational Animism in the Art and Archaeology theory; divination; spirit impersonation; material agency of Ancient Mesoamerica.