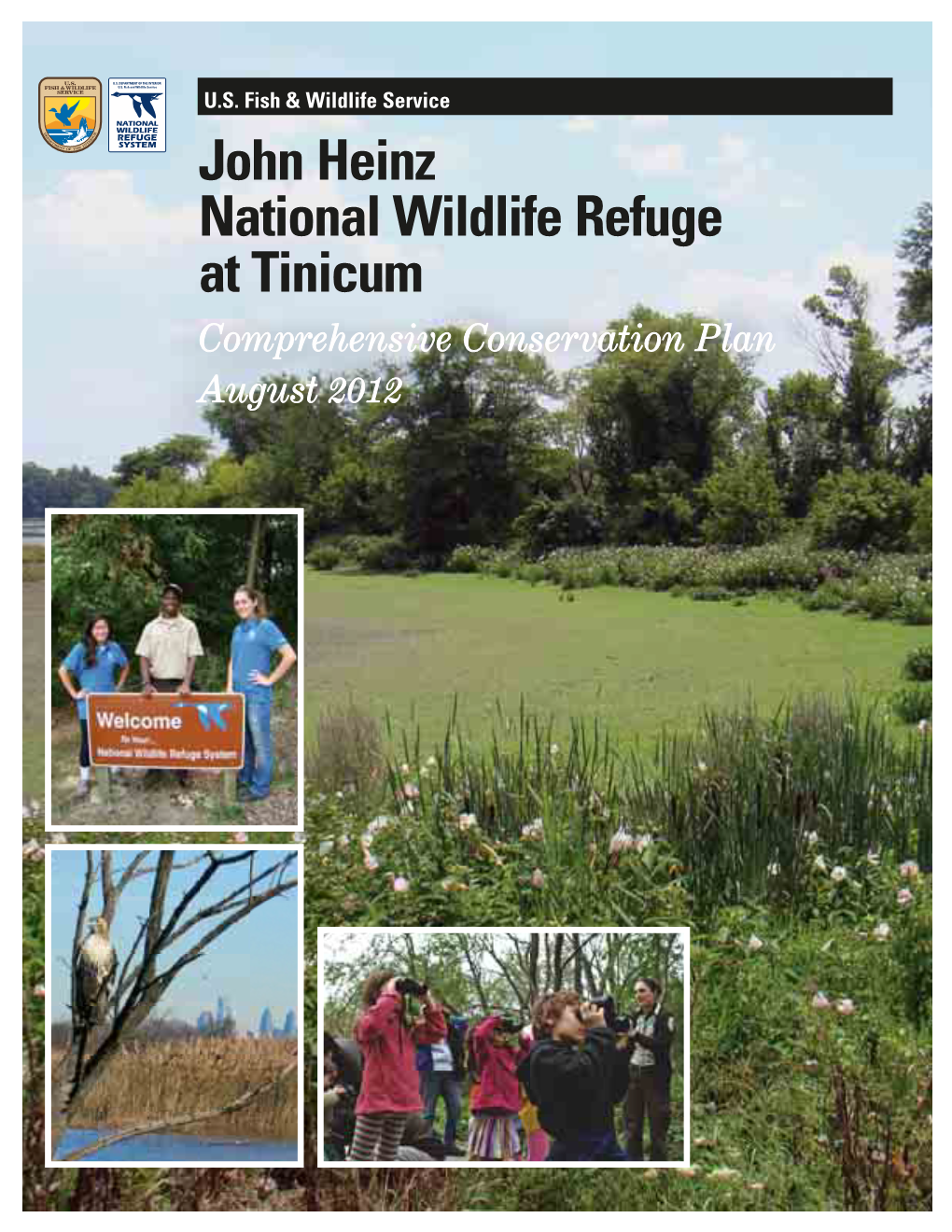

John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4 Reproductive Biology of Cerambycids

4 Reproductive Biology of Cerambycids Lawrence M. Hanks University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, Illinois Qiao Wang Massey University Palmerston North, New Zealand CONTENTS 4.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 133 4.2 Phenology of Adults ..................................................................................................................... 134 4.3 Diet of Adults ............................................................................................................................... 138 4.4 Location of Host Plants and Mates .............................................................................................. 138 4.5 Recognition of Mates ................................................................................................................... 140 4.6 Copulation .................................................................................................................................... 141 4.7 Larval Host Plants, Oviposition Behavior, and Larval Development .......................................... 142 4.8 Mating Strategy ............................................................................................................................ 144 4.9 Conclusion .................................................................................................................................... 148 Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................. -

Eastern Delaware County Stormwater Collaborative Pollutant Reduction Plan Supplemental Intergovernmental Agreement

Eastern Delaware County Stormwater Collaborative Pollutant Reduction Plan Date: April 10, 2018 C o n e s t o g a W a t e r s Prepared for: h Eastern Delawaree County Stormwater Collaborative d P.O. Box 315 A Morton, PA 19070 l l Prepared by: i a LandStudies, Inc. n 315 North Street c Lititz, PA 17543 e 717-627-4440 P www.landstudies.com O B o x 6 L 3 i 5 t 5 t Lancaster, PA 17607 l e L C i o t n t e l s e t Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 1 A. Public Participation ........................................................................................................... 2 C. Pollutants of Concern ........................................................................................................ 5 D. Existing Load for Pollutants of Concern ............................................................................ 6 D.1 Cobbs Creek Existing Load .............................................................................................................................. 7 D.2. Darby Creek Watershed Existing Load ........................................................................................................... 8 D.3 Total Existing Load and Percent Share of Loading for Budget Ratios and Pollution Reduction Credit ....... 9 E. BMPs Selected to Achieve the Minimum Required Reductions in Pollutant Loading .... 10 E.1. Background Information and Rationale ...................................................................................................... -

Range of Attraction of Pheromone Lures and Dispersal Behavior of Cerambycid Beetles

Annals of the Entomological Society of America Advance Access published August 6, 2016 Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 2016, 1–9 doi: 10.1093/aesa/saw055 Ecology and Population Biology Research article Range of Attraction of Pheromone Lures and Dispersal Behavior of Cerambycid Beetles E. Dunn,1,2 J. Hough-Goldstein,1 L. M. Hanks,3 J. G. Millar,4 and V. D’Amico5 1Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology, University of Delaware, 531 S. College Ave., Newark, DE 19716 ([email protected]; [email protected]), 2Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected], 3Department of Entomology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 505 S. Goodwin Ave. MC-118, Urbana, IL 61801 ([email protected]), 4Department of Entomology, University of California, 900 University Ave., Riverside, CA 92521 ([email protected]), and 5U. S. Forest Service, Northern Research Station, 531 S. College Ave., Newark, DE 19716 ([email protected]) Received 13 April 2016; Accepted 12 July 2016 Downloaded from Abstract Cerambycid beetles (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) can locate suitable hosts and mates by sensing pheromones and plant volatiles. Many cerambycid pheromone components have been identified and are now produced syn- thetically for trap lures. The range over which these lures attract cerambycids within a forest, and the tendency for cerambycids to move out of a forest in response to lures, have not been explored previously. We conducted http://aesa.oxfordjournals.org/ two field experiments using baited and unbaited panel traps in northern Delaware to investigate these ques- tions. Within forest fragments, unbaited traps that were 2 m from a baited trap captured more beetles than unbaited control traps, suggesting increased cerambycid activity leading to more by-catch in unbaited traps at 2 m from the pheromone source. -

5 Chemical Ecology of Cerambycids

5 Chemical Ecology of Cerambycids Jocelyn G. Millar University of California Riverside, California Lawrence M. Hanks University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urbana, Illinois CONTENTS 5.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 161 5.2 Use of Pheromones in Cerambycid Reproduction ....................................................................... 162 5.3 Volatile Pheromones from the Various Subfamilies .................................................................... 173 5.3.1 Subfamily Cerambycinae ................................................................................................ 173 5.3.2 Subfamily Lamiinae ........................................................................................................ 176 5.3.3 Subfamily Spondylidinae ................................................................................................ 178 5.3.4 Subfamily Prioninae ........................................................................................................ 178 5.3.5 Subfamily Lepturinae ...................................................................................................... 179 5.4 Contact Pheromones ..................................................................................................................... 179 5.5 Trail Pheromones ......................................................................................................................... 182 5.6 Mechanisms for -

A Check-List and Keys to the Primitive Sub-Families of Cerambycidae of Illinois

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1967 A Check-list and Keys to the Primitive Sub-families of Cerambycidae of Illinois Michael Jon Corn Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Zoology at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Corn, Michael Jon, "A Check-list and Keys to the Primitive Sub-families of Cerambycidae of Illinois" (1967). Masters Theses. 2490. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2490 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CHECK-LIST AND KEYS TO THE PRIMITIVE SUBFAMILIES OF CEHAMBYCIDAE OF ILLINOIS (TITLE) BY MICHAEL JON CORN B.S. in Ed., Eastern Illinois University, 1966 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Science IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL, EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON, ILLINOIS 1967 YEAR I HEREBY RECOMMEND THIS THESIS BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE GRADUATE DEGREE CITED ABOVE 21 rl.\I\( l'i "1 PATE ADVISER DEPARTMENT HEAD ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank Dr. Michael A. Goodrich for.his advice and guidance during the research and writing of this paper. The author is also indebted to the following curators of the various museums and private individuals from whom material was borrowed: Mr. John K. Bouseman; Dr. Rupert Wenzel and Dr. Henry Dybas, Field Museum ,...-._, of Natural History; Dr.'M. -

Habitat Management Plan

Appendix C Frank Miles/USFWS Frank Yellow-rumped warbler Habitat Management Plan John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum Habitat Management Plan August 2012 The National Wildlife Refuge System, managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, is the world’s premier system of public lands and waters set aside to conserve America’s fish, wildlife and plants. Since the designation of the first wildlife refuge in 1903, the System has grown to encompass more than 150 million acres, over 550 national wildlife refuges and other units of the Refuge System, plus 37 wetland management districts Appendix C. Draft Habitat Management Plan C-1 U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum Final Habitat Management Plan August 2012 Submitted by: Gary M. Stolz Date Refuge Manager John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum Concurrence by: Jan D. Taylor Date Chief, Division of Natural Resources, Region 5 National Wildlife System Susan R. McMahon Date Deputy Regional Chief, Region 5 National Wildlife System Approved by: Scott B. Kahan Date Regional Chief, Region 5 National Wildlife System Draft Habitat Management Plan – TOC Table of Contents Chapter 1. Introduction C-5 1.1 Scope and Rationale C-6 1.2 Legal Mandates C-6 1.3 Relation to Other Plans C-7 Chapter 2. Background C-11 2.1 Refuge Location and Description C-12 2.2 Geographical Setting C-12 2.3 Historical Perspective C-16 2.4 Climate Influences and Natural andAnthropogenic Disturbances C-20 2.5 Current Refuge Conditions C-20 Resources of Concern C-35 3.1 Introduction C-36 3.2 Potential Resources of Concern C-36 3.3 Biological Integrity, Diversity, and Environmental Health C-38 3.4 Priority Resources of Concern C-42 3.5 Priority Habitat Types and Associated Focal Species C-44 3.6 Conflicting Habitat Needs C-49 3.7 Adaptive Management C-50 Chapter 4. -

Eastern Delaware County Stormwater Collaborative Pollutant Reduction Plan Supplemental Intergovernmental Agreement

Eastern Delaware County Stormwater Collaborative Pollutant Reduction Plan Date: September 7, 2017 C o n e s t o g a W a t e r s Prepared for: h Eastern Delawaree County Stormwater Collaborative d P.O. Box 315 A Morton, PA 19070 l l Prepared by: i a LandStudies, Inc. n 315 North Street c Lititz, PA 17543 e 717-627-4440 P www.landstudies.com O B o x 6 L 3 i 5 t 5 t Lancaster, PA 17607 l e L C i o t n t e l s e t Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 1 A. Public Participation .............................................................................................................. 2 C. Pollutants of Concern ........................................................................................................... 5 D. Existing Load for Pollutants of Concern .............................................................................. 6 D.1 Cobbs Creek Existing Load .............................................................................................................................. 7 D.3 Existing Load and Percent Share of Loading for Budget Ratios and Pollution Reduction Credit ................ 8 E. BMPs Selected to Achieve the Minimum Required Reductions in Pollutant Loading .... 10 E.1. Background Information and Rationale ....................................................................................................... 10 E.2. BMP Sediment Reduction Calculations ...................................................................................................... -

The External Morphology of Prionus Laticollis Drury (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae)

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1938 The external morphology of Prionus laticollis Drury (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae). Charles H. Daniels University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Daniels, Charles H., "The external morphology of Prionus laticollis Drury (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae)." (1938). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 3097. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/3097 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. * UMASS/AMHERST * i r 12()66 0306 7791 9 FIVE COLLEGE | DEPOSITORY Ihe i xicrnai Morphology of l: non us iaticoliis Drury .(■ oleoptci a: Cora mb V/vc ida 9) ARCH I VE'Sj THESIS M 1938 0186 The External Morphology of Prionus laticollis Drury (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) Charles H. Daniels Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science Massachusetts State College A.mherst 1938 CONTENTS Page Introduction . 1 Species Studied - Prionus laticollis Drury . 2 General Morphology .*. 5 Head. 5 Head Capsule . 5 Antennae . 9 Mandibles *. 10 Maxillae ...... 11 Labium. 12 Thorax. 14 Pro thorax. 14 Pro thoracic leg... 16 Mesothorax .. 20 Mesothoracic leg -. 24 Me tathorax.. *... 24 Metathoracic leg .. 29 Wings and Axillaries .. 30 Abdomen. 35 Male Genitalia .. 38 Bibliography. 41 INTRODUCTION A coleopterist, Tanner, has pointed out that of the twenty thousand species of beetles listed by Leng in his Catalogue of the Coleoptera, probably not more than one-fourth can be identified positively from the original description. -

(Npl) Listing Package

NPL LISTING PACKAGE FOR THE LOWER DARBY CREEK AREA DELAWARE AND PHILADELPHIA COUNTIES, PENNSYLVANIA June 2001 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region III 1650 Arch Street Philadelphia, PA 19103 AR300147 1.0 INTRODUCTION Contained within this listing package are two complete documentation records for two separate sites. These sites are being grouped into a single listing consistent with CERCLA 105(a)(8)(B). The sections below present general information about the listing, the location of the sites, operations at the sites, the environmental conditions of Lower Darby Creek, other potentials sources of contamination to Lower Darby Creek and the geology of the area. General Information The Lower Darby Creek Area (LDCA) site as originally proposed consisted of multiple sources releasing or potentially releasing into the waters of Darby Creek and other nearby streams: the Clearview Landfill (Source 1), the Industrial Drive properties (Source 2), the Oily Sludge Disposal Area (Source 3), the Catalyst Disposal Area (Source 4), the former Delaware County Sewage Treatment Plant (Source 5), the former Delaware County Incinerator (Source 6), and the Folcroft Landfill and Annex (Source 7). After considering the public comments received for the LDCA (see the Support Document for the Revised National Priorities List Final Rule-June 14, 2001 for the public comments received), EPA decided to promulgate the LDCA as a grouping of two separate sites, the Clearview Landfill site and the Folcroft Landfill and Annex site, for administrative purposes. The single NPL listing facilitates the management of the investigation and cleanup of the releases to Darby Creek, which have affected or might affect the same portion of the creek, which includes fisheries, wetlands, and other sensitive environments, including the John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge (NWR) at Tinicum. -

Short-Term Response of Ground-Dwelling Macroarthropods to Shelterwood Harvests in a Productive Southern Appalachian Upland Hardwood Forest

Short-term Response of Ground-dwelling Macroarthropods to Shelterwood Harvests in a Productive Southern Appalachian Upland Hardwood Forest John Westby-Gibson, Jr., Cathryn H. Greenberg, Christopher E. Moorman, T.G. Forrest, Tara L. Keyser, Dean M. Simon, and Gordon S. Warburton Forest Service Southern Research Station e-Research Paper RP-SRS-59 December 2017 AUTHORS: John Westby-Gibson, Jr., Student, University of North Carolina at Asheville, Department of Biology, One University Heights, Asheville, NC 28804; Cathryn H. Greenberg, Research Ecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Bent Creek Experimental Forest, Asheville, NC 28806; Christopher E. Moorman, Professor, North Carolina State University, Fisheries, Wildlife, and Conservation Biology Program, Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources, Raleigh, NC 27695; T.G. Forrest, Professor, University of North Carolina at Asheville, Department of Biology, One University Heights, Asheville, NC 28804; Tara L. Keyser, Research Forester, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Bent Creek Experimental Forest, Asheville, NC 28806; Dean M. Simon, Wildlife Forester (retired), North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, 8676 Will Hudson Road, Lawndale, NC, 28090; and Gordon S. Warburton, Director of Western North Carolina Region (retired), North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, 783 Deepwoods Dr., Marion, NC 28752. Corresponding author: Cathryn H. Greenberg, Research Ecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station, Bent Creek Experimental Forest, Asheville, NC 28806; [email protected]. Product Disclaimer The use of trade, firm, or model names in this publication is for reader information and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture of any product or service. -

Project Listings

Chapter 9: Project Listings Highway Projects for the FY2021 TIP 8LMW4EKI-RXIRXMSREPP]0IJX&PERO DVRPC FY2021-2024 TIP for PA Final Version Pennsylvania - Highway Program (Status: TIP) Bucks MPMS# 12923 Bristol Road Extension SR:2025 LIMITS US 202 to Park Avenue Est Let Date: 12/8/2022 IMPROVEMENT Roadway New Capacity NHPP: MRPID:119 MUNICIPALITIES: Chalfont Borough; New Britain Borough; New Britain Township FC: 16 AQ Code:2035M PLAN CENTER: Town Center IPD: 14 PROJECT MANAGER: HNTB/N. Velaga CMP: Major SOV Capacity CMP Subcorridor(s): 8G, 12B Provide a two lane extension of Bristol Road from Business Route 202 to Park Avenue. When completed, this improvement will provide a two-lane bypass around Chalfont Borough which will eliminate trips on Business Route 202 and turning movements at the Business Route 202/PA 152 intersection. Project may involve relocation of SEPTA siding track, a bridge across the wetlands, widening the intersection at Bristol Road and Business Route 202 to provide right and left turning lanes, providing maintenance of traffic during construction, redesigning traffic signals and rail road crossing gates at Business Route 202 and Bristol Road extension and coordination with SEPTA. Project CMP (Congestion Management Process) commitments include sidewalks, signal and intersection improvements, turning movement enhancements, and coordination with SEPTA. See DVRPC’s 2016-2017 memorandum on supplemental strategies for details related to this project. TIP Program Years ($ 000) Phase Fund FY2021 FY2022 FY2023 FY2024 FY2025 FY2026 -

Forest Insect and Disease Conditions in Vermont 2019

FOREST INSECT AND DISEASE CONDITIONS IN VERMONT 2019 AGENCY OF NATURAL RESOURCES DEPARTMENT OF FORESTS, PARKS & RECREATION MONTPELIER - VERMONT 05620-3801 STATE OF VERMONT PHIL SCOTT, GOVERNOR AGENCY OF NATURAL RESOURCES JULIE MOORE, SECRETARY PETER WALKE, DEPUTY SECRETARY DEPARTMENT OF FORESTS, PARKS & RECREATION Michael C. Snyder, Commissioner Sam Lincoln, Deputy Commissioner Danielle Fitzko, Director of Forests http://www.vtfpr.org/ We gratefully acknowledge the financial and technical support provided by the USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Area State and Private Forestry that enables us to conduct the surveys and publish the results in this report. This document serves as the final report for fulfillment of the Cooperative Lands – Survey and Technical Assistance and Forest Health Monitoring programs. In accordance with federal law and U.S. Department of Agriculture policy, this institution is prohibited from discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, or disability. This document is available upon request in large print, Braille or audio cassette. FOREST INSECT AND DISEASE CONDITIONS IN VERMONT CALENDAR YEAR 2019 PREPARED BY: Barbara Schultz, Joshua Halman, and Elizabeth Spinney AGENCY OF NATURAL RESOURCES DEPARTMENT OF FORESTS, PARKS & RECREATION STATE OF VERMONT – DEPARTMENT OF FORESTS, PARKS & RECREATION FOREST RESOURCE PROTECTION PERSONNEL Barbara Schultz Joshua Halman Elizabeth Spinney Forest Health Program Manager Forest Health Specialist Invasive Plant Coordinator Dept. of Forests, Parks & Recreation Dept. of Forests, Parks & Recreation Dept. of Forests, Parks & Recreation 100 Mineral Street, Suite 304 111 West St. 111 West Street Springfield, VT 05156-3168 Essex Junction, VT 05452 Essex Junction, VT 05452-4695 Cell Phone: 802-777-2082 Work Phone: 802-279-9999 Work Phone: 802-477-2134 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Savannah Ferreira Mary Burnham Forest Health Specialist Environmental Scientist II Dept of Forests, Parks & Recreation Dept.