The Future of Books Related to the Law?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 2010, Corrected 3/31/10 ISSN: 0195-4857

TECHNICAL SERVICE S LAW LIBRARIAN Volume 35 No. 3 http://www.aallnet.org/sis/tssis/tsll/ March 2010, corrected 3/31/10 ISSN: 0195-4857 INSIDE: Technical Services Law Librarian From the Officers OBS-SIS ..................................... 3 to be added to HeinOnline! TS-SIS ........................................ 4 AALL Headquarters and William S. Hein & Co. signed an agreement Announcements on December 2, 2009 that will permit TSLL to become available in a Renee D. Chapman Award ....... 31 fully-searchable image-based format as part of HeinOnline’s Law Librarian’s TS SIS Educational Grants ...... 13 Reference Library. TSLL to be added to Hein ........... 1 The Law Librarian’s Reference Library, currently in beta version, is accessible by subscription at http://heinonline.org/HOL/Index?collection=lcc&set_ as_cursor=clear. At present if a library subscribes to Larry Dershem’s print Columns version of the Library of Congress Classification Schedules it has free access Acquisitions ............................... 5 to this reference library. As part of this HeinOnline library TSLL will join such Classification .............................. 6 classic works as Library of Congress Classification schedules, Cataloging Collection Development ............ 8 Service Bulletin, Subject Headings Manual, and the Catalog of the Library of Description & Entry ................... 9 the Law School of Harvard University (1909). For more information about the The Internet .............................. 10 Law Librarian’s Reference Library see Hein’s introductory brochure at http:// Management ............................. 14 heinonline.org/HeinDocs/LLReference.pdf. MARC Remarks....................... 15 OCLC ....................................... 18 We’re hopeful TSLL will be accessible on HeinOnline in time for the AALL Preservation .............................. 19 Annual Meeting in July, but no timetable has yet been set … so stay tuned! Private Law Libraries .............. -

Vortrag ICIC Wien 2010

A new type of Knowledge Transfer: The Knowledge Marketplace Dr. Gernot Gmelin, Novartis Knowledge Center , Basel Switzerland [email protected] Agenda . NOVARTIS Campus . Knowledge Marketplace . New Types of Information Retrieval and Infrastructure Services . Outlook / Discussion 2 A new Type of Knowledge Transfer: The Knowledge Marketplace © Dr. Gernot Gmelin Novartis Campus A former Industrial Area …. 3 A new Type of Knowledge Transfer: The Knowledge Marketplace © Dr. Gernot Gmelin Novartis Campus A former Industrial Area …. 4 A new Type of Knowledge Transfer: The Knowledge Marketplace © Dr. Gernot Gmelin Novartis Campus A former Industrial Area …. 5 A new Type of Knowledge Transfer: The Knowledge Marketplace © Dr. Gernot Gmelin Novartis Campus A former Industrial Area …. 6 A new Type of Knowledge Transfer: The Knowledge Marketplace © Dr. Gernot Gmelin Novartis Campus A former Industrial Area …. 7 A new Type of Knowledge Transfer: The Knowledge Marketplace © Dr. Gernot Gmelin NOVARTIS Campus Transformed into a Campus of Knowledge 8 A new Type of Knowledge Transfer: The Knowledge Marketplace © Dr. Gernot Gmelin NOVARTIS Campus Transformed into a Campus of Knowledge 9 A new Type of Knowledge Transfer: The Knowledge Marketplace © Dr. Gernot Gmelin NOVARTIS Campus Transformed into a Campus of Knowledge 10 A new Type of Knowledge Transfer: The Knowledge Marketplace © Dr. Gernot Gmelin NOVARTIS Campus Transformed into a Campus of Knowledge 11 A new Type of Knowledge Transfer: The Knowledge Marketplace © Dr. Gernot Gmelin Knowledge Marketplace Concept The Knowledge Marketplace (part of the Knowledge Center) . Serves as platform for information exchange . Consultancy in information retrieval regarding complex scientific, medical, technical, business information . Training in information retrieval technologies . -

Compatible Ebook Devices

Current as of 5/1/2012. For the most up-to-date list, visit overdrive.com/eBookdevices. Library Compatible eBook Devices eBooks from your library’s ‘Virtual Branch’ website powered by OverDrive® are currently compatible with a variety of readers, computers and devices. eBook readers Amazon® Kindle Sony® Other devices (U.S. libraries only) • Kindle • Daily Edition • Aluratek LIBRE • Kindle 2 • Pocket Edition Air/Color/Touch • Kindle 3 • PRS-505 • En Tourage Pocket eDGe™ • Kindle DX • PRS-700 • iRiver Story HD • Kindle Touch • Touch Edition • Literati™ Reader • Kindle Keyboard • Wi-Fi PRS-T1 • Pandigital® Novel ® ™ • PocketBook Pro 602 Barnes & Noble Kobo • Skytex Primer • NOOK™ 3G+Wi-Fi • Kobo eReader The process to download • NOOK Wi-Fi • Kobo Touch or transfer eBooks to these • NOOKcolor™ devices may vary by device, most require Adobe • NOOK Touch™ Digital Editions. • NOOK Tablet Mobile devices ™ Get the FREE OverDrive Media Console app for: Other devices BlackBerry® iPad®, iPhone® & iPod touch® Android™ • Acer Iconia • Nextbook™ Next 2 ™ ® • Agasio Dropad • Pandigital Nova Windows ™ ™ Phone 7 • Archos Tablets • Samsung Galaxy Tab • ASUS® Transformer • Sony Tablet S • Coby Kyros • Sylvania Mini Tablet • Cruz™ Reader/Tablet • Toshiba Thrive™ • Dell Streak • ViewSonic gTablet • EnTourage eDGe™ • Kindle Fire ...or use the FREE Available in Mobihand™ Available in the Available in • Kobo Vox Kindle reading app on ™ SM & AppWorld App Store Android Market • Motorola® Xoom™ many of these devices. Computers Install the FREE Adobe Digital Editions software to download and read eBooks on your computer and transfer to eBook readers. Windows® XP, Vista or 7 Mac OS X v10.4.9 (or newer) OverDrive and your library are not affiliated with and do not endorse any of the devices or manufacturers listed above. -

REACH: Leading Learning in Libraries June 2, 2010 Minutes

REACH: Leading Learning in Libraries June 2, 2010 Minutes Location: Douglas County Libraries Philip S. Miller Library 100 South Wilcox Street Castle Rock, CO 80104 Attendees: First Last Affiliation Shelly Drumm CDE – State Library – Digital Services Mary Beth Faccioli CDE – State Library – Instructional Design & Technology Su Eckhardt University of Colorado Denver Michelle Gebhart CDE – State Library – Library Development Don Jenkins Pikes Peak Library District Mindy Kittay Anythink Libraries (Rangeview) Sharon Morris CDE – State Library – Library Development Nance Nassar CDE – State Library – Schools Joseph Sanchez Red Rocks Community College Library Missy Shock Douglas County Libraries Sandra Smith Denver Public Library Elizabeth Snow Trenkle DU Student (doing practicum w/ Mary Beth & Sharon Kelly Visnak Emporia State University Roles Facilitator – Missy Shock, Sharon Morris Meeting minutes – Michelle Gebhart Participants – All involved in CE for Colorado library staff Outcomes Updates from various libraries Hands-on sharing of tech tools and toys. Minutes: 1. Updates a. Sandra i. Training pages: one-stop shop for staff development. Would be glad to share database with group once it is finished. ii. ALA roundtable – Learn. www.alalearning.org iii. ALA presentations: competencies in libraries, and trainers as leaders within their library. b. Missy i. Just switched over to active directory. ii. All public service staff is doing the Colorado Libraries 2.0 training. Wide range of ability. Staff have enjoyed doing this. c. Mindy i. First batch of staff finished the Colorado Libraries 2.0 training, and they loved it. Very positive comments. Great mix of skill levels. Plans on doing another round of training later on. ii. -

New Technologies

Department of Curriculum, Instruction and Technology CIT ESPONS E R April 2010 What’s Inside New Technologies New Technologies and Resources by Cliff Steinberg Spotlight n February, we saw the release of a Tech Toys I device that could hold many exciting A is for Apple. NASTECH News possibilities for education. Sure, it’s a little too early to talk about what its Upcoming Events impact will be, but it definitely is fun to and more... give it some thought. Of course, this device is the iPad from Watch for our May issue Apple. Being touted as “the best way to featuring Creativity and experience the Web, e-mail, photos, and Balance video,” the potential uses for the device in the classroom are many. That being Since we are true believers in educating said, one of the most anticipated features students to be 21st Century learners, the of the device, from an educational per- discussion moves to competencies such spective, is its ability to handle ebooks as creation and innovation. With all of this Board of Cooperative ... or should we say textbooks! Its ability said, the new iPad is slightly disappoint- Educational Services of to store either a simple textbook supple- ing. The device still seems targeted to the Nassau County ment or a full replacement is extremely consumer market and consuming content Stephen B. Witt, President compelling. The iPad is able to do many rather than to the educational market. Eric B. Schultz, Vice President things in a small and compact form. We, as educators, want something that Susan Bergtraum, District Clerk Add the capability to browse the Web, will allow students to produce and experi- Michael Weinick, view video (no Flash), and perform basic ence content in new and innovative ways. -

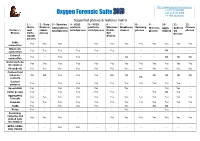

Oxygen Forensic Suite

http://www.oxygen-forensic.com +1 877 9 OXYGEN Oxygen Forensic Suite +44 20 8133 8450 +7 495 222 9278 Supported phones & features matrix 1 – 2 - Sony 3 – Symbian 4 - UIQ2 5 – UIQ3 6 - 7 - 8- 9- 10- 11- 12- Nokia Ericsson S60 platform platform platform Windows Blackberry Samsung Motorola Apple Android Chinese Feature \ and classic smartphones smartphones smartphones Mobile devices phones phones devices OS phones Phones Vertu phones 5/6 devices classic devices phones Cable Yes Yes Yes - Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes connection Bluetooth Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes - - - NA - - connection Infrared Yes - Yes Yes - - NA - - NA NA NA connection General phone Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes information Phonebook Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Custom field labels for NA NA Yes Yes Yes NA NA NA NA NA NA contacts NA Contact Yes - Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes - pictures Speed dials Yes - Yes Yes Yes - Yes - - Yes Yes - Caller groups Yes - Yes Yes Yes Yes - - Yes NA Yes - Aggregated Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Contacts Calendar Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Tasks Yes - Yes Yes Yes - Yes - NA NA - - Notes Yes - - - - - Yes - - Yes - - Incoming, outgoing and Yes Yes Yes - - Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes missed calls information GPRS, EDGE, - - Yes Yes - - - - - - - CSD, HSCSD - and Wi-Fi traffic and sessions log Sent and received SMS, - Sent SMS - Yes Yes Yes(2) - - - - - - MMS, E-mail messages log Deleted - messages - - Yes(1) - Yes(1) - - - Yes(8) - - information Flash SMS -

FOR MORE INFORMATION CONTACT: for IMMEDIATE RELEASE Caroline Sherman May 25, 2010 312-245-9805 Ext

FOR MORE INFORMATION CONTACT: FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Caroline Sherman May 25, 2010 312-245-9805 ext. 110 [email protected] ENTOURAGE SYSTEMS PARTNERS WITH THE DOUGLAS STEWART COMPANY FOR EDUCATION DISTRIBUTION OF THE ENTOURAGE EDGE™ World’s first dualbook™ to enhance learning with innovative, interactive platform McLean, VA – enTourage Systems, Inc., creator of the world’s first dualbook™ – the enTourage eDGe™ – announced today that it has partnered with The Douglas Stewart Company, a leading distributor and marketer of computer products, consumer electronics and school supplies, to exclusively serve the education market and boost interactive learning for school systems’ students, faculty and staff. The enTourage eDGe is the first device to merge an e-paper and LCD screen to create a dual- screen device that combines the functionality of an e-reader, tablet netbook, notepad and audio/video recorder and player in one inclusive device. These two displays work together to allow students to access and enrich information in a way that they previously couldn’t. Students can access their textbooks and make notes in the margins or highlight text while they simultaneously look up further information on the subject via the Web on the LCD side. Last year, The Douglas Stewart Company began including hardware in its distribution, and this is the first time the company has partnered with a manufacturer of an e-reading device to offer retailers the most current technology that students need. “Our partnership with The Douglas Stewart Company strengthens our mission to bring the enTourage eDGe directly to students and educational institutions and allows us to reach the right resellers and end users,” said Asghar Mostafa, CEO of enTourage Systems, Inc. -

From the Editor

From the Editor Guanrong (Ron) Chen Editor-in-Chief, IEEE Circuits and Systems Magazine -publishing: appalling or appealing? tional newspaper publishing business. The 146-year-old On March 17 this year, Arthur Sulzberger Jr., well-established Seattle Post published its last print ver- Epublisher of The New York Times (NYT) and chair- sion on March 17, 2009 and was then converted entirely man of the board of the NYT company, wrote in “A Let- to an e-newspaper, followed by another popular cen- ter to Our Readers About Digital Subscriptions” on the tury-old newspaper, the Christian Science Monitor. Two website www.nytimes.com: other longstanding U.S. newspapers, the Tucson Newspa- per People and the Ann Arbor News, also stopped their “Today marks a significant transition for The New mechanical printers in 2009, prior to the now-declining York Times as we introduce digital subscriptions. print version of the NYT. More recently in February … On March 28, we will begin offering digital sub- this year, the second-largest U.S. bookstore chain Bor- scriptions in the U.S. and the rest of the world.” ders filed for bankruptcy protection, while the largest U.S. bookstore chain Barnes & Noble stays intact mainly The NYT was founded in New York City in 1851 and con- due to the success of its Nook e-book reader sales and tinuously published as the largest local metropolitan online services. newspaper in the U.S. It has been considered a model On the bright side, e-publishing brings to the whole and flagship newspaper worldwide, with the motto “All of society (not just to academia) many advantages and the News That’s Fit to Print” appearing in the upper left- benefits as well as resources and opportunities. -

Download This PDF File

Chapter X Resources http://www.alatechsource.org/blog/2008/08/library Dybwad, Barb. “9 Upcoming Tablet Alternatives to -technology-in-a-slow-economy.html the Apple iPad.” Mashable: The Social Media Guide website, Jan. 28, 2010, http://mashable. com/2010/01/27/9-upcoming-tablet-alternatives-to- E-readers and Tablets the-apple-ipad (accessed Feb. 6, 2010). E Ink. “First-Generation Electronic Paper Display Allen, Danny. “The Intel Reader Photographs Text and from Philips, Sony and E Ink to Be Used in New Reads It Back to You.” Gizmodo website, Nov. 10, Electronic Reading Device” (press release). March 2009, http://gizmodo.com/5401168/the-intel- 24, 2004, www.eink.com/press/releases/pr70.html reader-photographs-text-and-reads-it-back-to-you (accessed Feb. 6, 2010). (accessed Feb. 6, 2010). E Ink Press Archives. http://eink.com/press/archives. Amazon Kindle Team. “Announcement: Macmillan html (accessed Feb. 6, 2010). E-books.” Amazon.com website, Kindle Community section, Jan. 31, 2010, www.amazon.com/tag/ enTourage eDGe Store. www.entourageedge.com kindle/forum/ref=cm_cd_tfp_ef_tft_tp?_encodin (accessed Feb. 6, 2010). g=UTF8&cdForum=Fx1D7SY3BVSESG&cdThrea Golijan, Rosa. “Borders and Kobo Team Up to Develop d=Tx2MEGQWTNGIMHV&displayType=tagsDetail a New Reader.” Gizmodo website, Dec. 15, 2009, (accessed Feb. 6, 2010). http://gizmodo.com/5427513/borders-and-kobo- Best Tablet Review. “Kindle Claims 45% of eReader team-up-to-develop-a-new-reader (accessed Feb. 6. April 2010 April Market, Sony Claims 30%.” Sept. 1, 2009. http:// 2010). besttabletreview.com/kindle-claims-45-percent-of- Jhonsa, Eric. “Amazon Has an Early Lead, but the ereader-market-sony-claims-30-percent (accessed Feb. -

Introducing the World's First Dualbooktm

Introducing the world’s first dualbookTM The enTourage eDGeTM is a multi- cations, with new applications media organizer, allowing you to being developed every day. carry books, documents, presenta- You can customize the enTou- tions, movies, and music in a mid- rage eDGe with applications, sized mobile Internet device com- tools, and games just like a cell bining an electronic document phone. reader with a tablet netbook. The No worries multimedia library allows you to Dual functionality With the enTourage eDGe you nev- organize all of your files by class, The enTourage eDGe’s dual dis- er forget your books, documents client, subject, or customer and play enables the flexibility to read or notes because they are stored mix documents, books, music, and surf simultaneously on one on the device. You can never and video together as integrated small device. With the 9.7” diago- lose your notes because they are attachments to each other that nal e-paper display you can read backed up on enTourage’s servers. can then be shared with other us- PDF files or e-books. On the 10.1” Should you ever lose or break a ers. The enTourage eDGe replaces LCD screen you can surf the In- device, all of your information can thirty pounds of books and docu- ternet, send emails, check Face- be easily restored right from our ments with a single 3-pound de- book®, play MP3s, or watch mov- servers. vice for all reading, writing, email, ies. and Internet access needs. Use it all day The e-reader Have it all The enTourage eDGe is designed The e-paper display incorporates with a battery incorporating ad- The enTourage eDGe combines Penabled® technology for digi- vanced power-saving modes to the readability of an e-reader with tally annotating documents and maximize battery life, providing the services of a tablet netbook. -

A Mano Alzada

UNIVERSITAT POLITÈCNICA DE VALÈNCIA Departamento de Informática de Sistemas y Computadores Propuesta Metodológica para el Uso de las Tecnologías de Tinta Digital en los Procesos Formativos del Ámbito de la Educación Superior Tesis Doctoral Autor José-V. Benlloch-Dualde Directores Dr. Félix Buendía García Dr. Juan Carlos Cano Escribá Junio de 2014 A mis padres, Isabel y José María, en deuda de gratitud por todo lo que hicieron por mí. Agradecimientos En primer lugar quiero agradecer toda su dedicación, paciencia y constante aliento a mis directores de tesis, Félix y Juan Carlos. Estoy seguro de que sin ellos esta aventura, ni siquiera hubiera comenzado. A los colegas del equipo de innovación iNNOVATiNK y, muy especialmente, a Lenin Lemus, Pedro Gil, Nati Prieto, Ángel Perles, Jorge Más, Sara Blanc, Carlos Herrero, Daniela Gil, y Adelina Bolta, pues su colaboración ha sido fundamental para la realización de este trabajo. A la dirección de la ETSINF, y muy especialmente a su director, Eduardo Vendrell, y a Miguel Sánchez, que siempre creyeron en nuestro proyecto y lo apoyaron constantemente. A Emilio Bayo, a Juanma García, y al resto de técnicos de la ETSINF y del DISCA, que siempre tuvieron a punto las infraestructuras necesarias para poder desarrollar este trabajo. A Vicky Gutiérrez, por su inestimable colaboración en la parte experimental del mismo. A mi buen colega Oscar Martínez Bonastre, al que tuve la suerte de conocer en un evento hace ya bastantes años y ha sido, sin duda, uno de los que más me ha enseñado en este ámbito. A Vicent Esteban Chapapría, Miguel Ferrando y Miguel Ángel Fernández de Prada, por ofrecerme la oportunidad de presentar el proyecto de innovación a Hewlett Packard, que se convirtió en el germen de todo este trabajo. -

Digital Course Materials: a Case Study of the Apple Ipad in the Academic Environment

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations 2011 Digital course materials: a case study of the Apple iPad in the academic environment Michael H. Bush Andrea H. Cameron Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd Recommended Citation Bush, Michael H. and Cameron, Andrea H., "Digital course materials: a case study of the Apple iPad in the academic environment" (2011). Theses and Dissertations. 133. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd/133 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Pepperdine University Graduate School of Education and Psychology DIGITAL COURSE MATERIALS: A CASE STUDY OF THE APPLE IPAD IN THE ACADEMIC ENVIRONMENT A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Educational Technology by Michael H. Bush and Andrea H. Cameron May, 2011 Ray Gen, Ed.D. – Dissertation Chairperson This dissertation, written by Michael H. Bush and Andrea H. Cameron under the guidance of a Faculty Committee and approved by its members, has been submitted to and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Doctoral Committee: Ray Gen, Ed.D., Chairperson Paul Sparks, Ph.D. John Garofano, Ph.D. © Copyright by Michael H. Bush and Andrea H. Cameron (2011) All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................