Accounting Historians Journal, 1997, Vol. 24, No. 1 [Whole Issue]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entire Issue (PDF)

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 114 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 162 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, MARCH 17, 2016 No. 43 House of Representatives The House met at 9 a.m. and was point of order that a quorum is not Gunny Stanton first began his train- called to order by the Speaker. present. ing, he attended the basic EOD course f The SPEAKER. Pursuant to clause 8, at Eglin Air Force Base. While in train- rule XX, further proceedings on this ing, his block tests and final examina- PRAYER question will be postponed. tion scores were so high that his The Chaplain, the Reverend Patrick The point of no quorum is considered records remain intact to this day. J. Conroy, offered the following prayer: withdrawn. In the course of his 18 years in the Marine Corps, Stanton earned many Merciful God, thank You for giving f us another day. awards too numerous to list in this Your care and wisdom are shown to PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE space. He is preceded in death by his fa- us by the way You extend Your king- The SPEAKER. Will the gentleman ther, Michael Dale Stanton Sr.; and a dom into our world down to the present from Texas (Mr. VEASEY) come forward brother, Brian Stanton. Gunny Stanton day. Your word reveals every aspect of and lead the House in the Pledge of Al- is survived by his loving family: his Your saving plan. You accomplish Your legiance. wife, Terri Stanton; his mother, Gloria designed purpose in and through the Mr. -

GAO: Reporting the Facts, 1981-1996, the Charles A. Bowsher Years

GAO: REPORTING THE FACTS, 1981-1996 The Charles A. Bowsher Years Maarja Krusten, GAO Historian A GAO: REPORTING THE FACTS, 1981-1996 The Charles A. Bowsher Years Maarja Krusten, Historian U.S. Government Accountability Office Washington, DC January 2018 Contents 1. PREFACE: GAO Sounds the Alarm on a Major Financial Crisis ................................................... 1 2. Setting the Scene ........................................................... 8 GAO’s evolution from 1921 to 1981 .............................. 9 Charles A. Bowsher’s background, 1931-1981 ..............14 3. Bowsher’s Early Assessments of GAO’s Organization and Operations ...................................... 25 4. Managing the Cost of Government and Facing the Facts on the Deficit .................................... 48 5. Early Examinations of Reporting and Timeliness ....................................................................57 6. Managing and Housing a Diverse and Multi-Disciplinary Workforce .................................... 66 7. Pay for Performance .................................................... 89 8. Re-Establishment of GAO’s Investigative Function ....................................................................... 94 9. Looking at the Big Picture .........................................101 10. The Broad Scope of GAO’s Reports ..........................106 11. GAO’s Position Within the Government ....................119 12. Client Outreach and Quality Management .................125 GAO’s quality management initiative ........................128 -

LCD-74-110 Ways to Improve Management of Automated Data

111111111llllllll11111Ill11lllll llllllllllllll Ill1 LM097054 Oegartment of the Navy COYFI’ROLL?ZR GENCRAL OF TIcIT UN:TCD S’hATCS WAmiIN6TOH. DC 20840 B-146796 ho the President of the Senate and the Speaker of the House of Representatives This is our report on ways for the Department of the Navy to improve its management of automated data processing resources. We made our review pursuant to the Budget and Account- ing Act, 1921 !31 U.S.C. 53), and the Accounting and Audit- ing Act of 1950 (31 G.S.C. 67). We are sending copies of this report to Off ice of Management and Budget; the and the Secretary of the Navy. Comptroller General of the onited States -. contents *. Page DIGEST i CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION - 1 Department of the Navy's automatic data processing prograim 1 Cbjectivcs and principles of the Navy program 1. 2 ADVERSE EFFECTS OF PROLONGEDSYSTEMS DEVELOPMENT 3 Has the program been successful? 3 How has prolonged systems development affected automated data processing resources and benefits? 6 3 OPPORTUNITIES TO IMPROVE NAVY'S MANAGEMENT OF AUTOMATED DATA PROCESSING RESOURCES 9 Why hasn't standardization been successful? 9 How can the program be improved? 10 Need for studies before acquiring computer equipment 10 Need to imprcve and extend stand- ard systems 12 Need to enforce redesign policy 18 Need to improve process af justi- fying system projects 20 4 CONCLUSIONS, AGENCY COMMENTSAND OUR EVALUATION, AND RECOY%%ENDATIONS 23 Conclusions 23 Agency co.mments and our evaluation 24 Recommendations to the Secretary ot the Navy 30 5 SCOPE -

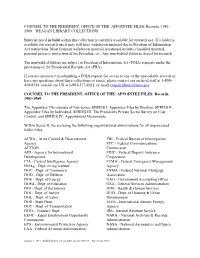

APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981- 1989 – REAGAN LIBRARY COLLECTIONS

COUNSEL TO THE PRESIDENT, OFFICE OF THE: APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981- 1989 – REAGAN LIBRARY COLLECTIONS Material noted in bold within this collection is currently available for research use. If a folder is available for research use it may still have withdrawn material due to Freedom of Information Act restrictions. Most frequent withdrawn material is national security classified material, personal privacy, protection of the President, etc. Any non-bolded folder is closed for research. The non-bolded folders are subject to Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests under the provisions of the Presidential Records Act (PRA). If you are interested in submitting a FOIA request for access to any of the unavailable records or have any questions about these collections or series, please contact our archival staff at 1-800- 410-8354, outside the US at 1-805-577-4012, or email [email protected] COUNSEL TO THE PRESIDENT, OFFICE OF THE: APPOINTEE FILES: Records, 1981-1989 The Appointee File consists of four series: SERIES I: Appointee Files by Position; SERIES II: Appointee Files by Individual; SERIES III: The President's Private Sector Survey on Cost Control, and SERIES IV: Appointment Memoranda Within Series II, we are using the following organizational abbreviations for all unprocessed folder titles: ACDA - Arms Control & Disarmament FBI - Federal Bureau of Investigation Agency FCC - Federal Communications ACTION Commission AID - Agency for International FDIC - Federal Deposit Insurance Development Corporation CIA - Central Intelligence Agency FEMA - Federal Emergency Management DOAg - Dept. of Agriculture Agency DOC - Dept. of Commerce FNMA - Federal National Mortgage DOD - Dept. of Defense Association DOE - Dept. -

B-172632 Too Many Crew Members Assigned Too Soon to Ships Under

REPORT TO THE CONGRESS Too Many Crew Members Assigned Too Soon To Ships Under Construction 80172632 Department of the Navy BY THE COMPTROLLER GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES 5s COMPTROLLER GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES WASHINGTON DC 20242 B-172632 To the President of the Senate and the ii Speaker of the House of Representatives This IS our report on too many crew members assigned / t too soon by the Department of the Navy to ships under con- / struction Our review was made pursuant to the Budget and Account- mg Act, 1921 (31 U S C 53), and the Accounting and Audltmg Act of 1950 (31 U S C 67) Copies of this report are being sent to the Dlrector, Of- fice of Management and Budget, the Secretary of Defense, and the Secretary of the Navy 4. Comptroller General of the United States 50 TH ANNIVERSARY 1921-1971 I I i I I .qOMPTROLLERGEflER4L'S TOO MANY CREW MEMBERSASSIGNED TOO SOON TO 1 REPORTTO THE COflGRESS SHIPS UNDER CONSTRUCTION I I Department of the Navy B-172632 I I I I ------DIGEST I I I I WHYTHE REVIEW WASM4DE I I I The Navy assigns nucleus or skeleton crews for temporary duty periods I up to 6 months to ships under construction to ensure delivery of ships I I with tralned, well-organized crews I I I Since the assignment of nucleus crews of experienced personnel to ships I at construction sites involves a significant amount of valuable man- I I power and since the payment of per diem to these crew members while on temPorarv duty increases ship construction costs, the General Ac- I I counti iig of+1 ce ]GAO) examined into whether personnel -

A Nação E O Nacionalismo (Neo) Conservador Nos Estados Unidos (1981-1988)

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL FLUMINENSE INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIA HUMANAS E FILOSOFIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA CURSO DE MESTRADO EM HISTÓRIA Reaganation: a nação e o nacionalismo (neo) conservador nos Estados Unidos (1981-1988) Roberto Moll Neto Niterói, 2010 Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL FLUMINENSE INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIA HUMANAS E FILOSOFIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA CURSO DE MESTRADO EM HISTÓRIA Reaganation: a nação e o nacionalismo (neo) conservador nos Estados Unidos (1981-1988) Dissertação de mestrado apresentada ao programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Universidade Federal Fluminense como pré-requisito à obtenção do diploma de mestrado. Orientador: Profª. Drª Cecília Azevedo Roberto Moll Neto Niterói, 2010 2 Reaganation: a nação e o nacionalismo (neo) conservador nos Estados Unidos (1981-1988) Dissertação de mestrado apresentada ao programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Universidade Federal Fluminense como pré-requisito à obtenção do diploma de mestrado. Roberto Moll Neto BANCA EXAMINADORA ______________________________________________________________________ Profª. Drª. Cecília Azevedo - Orientadora Universidade Federal Fluminense ______________________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Marco Antonio Pamplona - Arguidor Universidade Federal Fluminense ______________________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Flávio Limoncic - Arguidor Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro 3 AGRADECIMENTOS -

Intosai at a Glance

Bujar BUJAR LESKAJ Leskaj Goverment Najwyższa Accountability Izba Office Kontroli GAO NIK dhe Experentia mutua Omnibus prodest Leksionet e DODAROS Seria botime KLSH -011/2019/113 Adresa: Rruga “Abdi Toptani”, Nr.1, Tiranë email: [email protected] Shtypur: Shtypshkronja “Classic Print: ISBN: GAO, NIK dhe Leksionet e DODAROS Tiranë, 2020 BUJAR LESKAJ GAO, NIK DHE LEKSIONET E DODAROS Institucionet Supreme të Auditimit të SHBA (GAO), Republikës së Polonisë (NIK) dhe Leksionet e Kontrollorit të Përgjithshëm të GAO-s, z. GENE L. DODARO Seria : botime KLSH: 11/2019/112 ISBN: 978-9928-4573-2-5 Tiranë, Janar 2020 BUJAR LESKAJ GAO, NIK dhe Leksionet e DODAROS Tiranë, Janar 2020 Dedikim: Drejtuesve më të lartë të NIK-ut polak në vitet 2007-2019, Presidentëve Jacek Jezierski, Krzysztof Kwiatkovski, zv. Presidentit Wojciech Kutyla dhe Drejtorit të Planifikimit dhe Zhvillimit Strategjik në GAO, James-Christian Blockwood Autori Titulli: GAO, NIK DHE LEKSIONET E DODAROS Redaktoi: Fatos Çoçoli Elsona Papadhima Realizoi në kompjuter: Benard Haka Erald Kojku Kopertina: Kozma Kondakçiu Seria: botime KLSH 11/2019/112 ©Copyright AUTORI ISBN: 978-9928-4573-2-5 Shtypur në Shtypshkronjën “Classic Print” Tiranë, Janar 2020 Shënim: Ky libër botohet në kolanën Seria “Botime KLSH”, por me kontributin financiar të Autorit dhe do të shpërndahet falas për audituesit e KLSH-së, Zyrës Kombëtare të Auditimit të Kosovës, si dhe për partnerët e KLSH-së. PËRMBAJTJA Hyrje: Triptik auditi me vlera universale .......................................................... 7 PJESA E PARË Kapitulli I – GAO: Integritet, pavarësi dhe profesionalizëm .........1111 1. Vështrim tangencial mbi jetën politike dhe institucionale në SHBA ........... 14 2. GAO – Misioni, qëllimi, parimet dhe strategjia e zhvillimit ........................ -

National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Updated 19-March-2010 (release letter added to file) Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

1989-1990.Pdf

1989-90 Institute of Politics Jotiii FeKeniiedy School of Governmeiit Harvard University PROCEEDINGS Institute of Politics 1989-90 John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University FOREWORD The Institute of Politics participates in the democratic process through the many and varied programs it sponsors. The programs include fellowships for individuals from the world of polihcs and the media, a program to encourage undergraduate and graduate students to get involved in the practical aspects of political activity, training programs for elected officials, seminars and conferences, and a public events series in the ARCO Forum of Public Affairs presenting speakers and panel discussions address ing contemporary political and social issues. On Janury 1,1990, as a new year—and a new decade—opened, the Institute began a new chapter with the arrival of Charles Royer, three-term Mayor of Seattle, as Institute Director. On that same date, Shirley Williams, having completed her one-year tenure as Acting Director, returned full time to her teaching responsibilities as Public Service Professor of Electoral Politics at the Kennedy School of Government. Programs and activities sponsored by the Institute during academic year 1989-90 are reflected in this twelfth edition of Proceedings. The Readings section provides a sense of the actors encountered and the issues discussed. The programs section details the people involved and subjects covered by the many undertakings of the student program—study groups, twice-weekly suppers, visits by distinquished visiting fel lows, internships, grants for summer research, a quarterly magazine, the Harvard Political Review, and a variety of special projects. Also included is information on fellows, participants in seminars and conferences and public events held in the Forum. -

Neo)Conservador Nos Estados Unidos (1981-1988

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL FLUMINENSE INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIA HUMANAS E FILOSOFIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA CURSO DE MESTRADO EM HISTÓRIA Reaganation: a nação e o nacionalismo (neo) conservador nos Estados Unidos (1981-1988) Roberto Moll Neto Niterói, 2010 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL FLUMINENSE INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIA HUMANAS E FILOSOFIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA CURSO DE MESTRADO EM HISTÓRIA Reaganation: a nação e o nacionalismo (neo) conservador nos Estados Unidos (1981-1988) Dissertação de mestrado apresentada ao programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Universidade Federal Fluminense como pré-requisito à obtenção do diploma de mestrado. Orientador: Profª. Drª Cecília Azevedo Roberto Moll Neto Niterói, 2010 2 Reaganation: a nação e o nacionalismo (neo) conservador nos Estados Unidos (1981-1988) Dissertação de mestrado apresentada ao programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Universidade Federal Fluminense como pré-requisito à obtenção do diploma de mestrado. Roberto Moll Neto BANCA EXAMINADORA ______________________________________________________________________ Profª. Drª. Cecília Azevedo - Orientadora Universidade Federal Fluminense ______________________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Marco Antonio Pamplona - Arguidor Universidade Federal Fluminense ______________________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Flávio Limoncic - Arguidor Universidade Federal do Estado do Rio de Janeiro 3 AGRADECIMENTOS Sou grato a todos os professores do departamento de História da Universidade Federal Fluminense, que de alguma forma contribuíram para a fertilização das idéias que floresceram neste trabalho. Agradeço aos funcionários do departamento de história da Universidade Federal Fluminense, que sempre foram prestativos, eficientes e simpáticos em todos os momentos que puderam ajudar. Agradeço ao Prof. Dr. Marco Antônio Pamplona, com quem comecei a pesquisar historia, mais especificamente a história dos Estados Unidos, e que contribuiu com críticas e idéias para a feitura deste trabalho. -

Pull Together Spring 2014

Preservation, Education, and Commemoration Vol. 53, No. 2 Spring 2014 PULL TOGETHER Newsletter of the Naval Historical Foundation Operation Sea Orbit 50th Anniversary Join Us in Norfolk! Details Page 10 News from Our Shipmate, the Director of Naval History: Page 3 Also in this issue: Submarine Seminar Recap, pp. 7-9; Navy Museum News STEM-H Update, pp. 11-14; News from the NHF, pp. 16; NHF Annual Report, pp 19-22; Thank You End-of-Year Donors! p. 23 Message From the Chairman If you were surprised to fi nd this early spring Pull Together in your mailbox, we hope it was a pleasant surprise! There is much activity occurring at your Naval Historical Foundation— and at the Naval History and Heritage Command, whose programs and museum we support. With the pending retirement of the Director of Naval History, Capt. Henry J. (Jerry) Hendrix, this summer, we thought it would be appropriate to feature his views on the progress the com- mand has made over his two-year tenure. We congratulate Captain Hendrix on a fi ne career and commend him for what he has been able to accomplish. Coming up quickly on April 3 is the annual Submarine History Seminar that is the out- growth of a continuing partnership with the Naval Submarine League. Dr. David A. Rosenberg has taken over the direction of this year’s seminar, following Rear Adm. Jerry Holland’s de- cade of great programs. Dave has assembled an outstanding panel to discuss “A Century of US Navy Torpedo Development.” There are details in this issue; I hope to see you there! Dr. -

1991 Journal

OCTOBER TERM, 1991 Reference Index Contents: Page Statistics n General m Appeals in Arguments in Attorneys in Briefs iv Certified Questions iv Certiorari iv Costs and Damages iv Judgments, Mandates and Opinions iv Original Cases v Parties v Records v Rehearings v Stays v Conclusion vi (i) II STATISTICS AS OF JUNE 29, 1992 In Forma Paid Pauperis Total Original Cases Cases 12 2,451 4,307 6,770 1 2,072 3,755 5,828 11 379 552 942 Cases docketed during term: 2 086 Paid cases • • —— ' In forma pauperis cases 3,779 Original cases... • 5,866 Total........ • • 904 Cases remaining from last term 6 ,770 Total cases on docket • • 5 ,828 Cases disposed of • 942 Number remaining on docket • Petitions for certiorari granted: 98 In paid cases • 17 In in forma pauperis cases Appeals granted: 5 In paid cases..... ••••• 0 In in forma pauperis cases 120 Total cases granted plenary review 127 Cases argued during term 120 Number disposed of by full opinions Number disposed of by per curiam opinions 3 4 Number set for reargument next term 69 Cases available for argument at beginning of term... 3 Disposed of summarily after review was granted 2 Original cases set for argument 75 Cases reviewed and decided without oral argument 66 Total cases available for argument at start of next term 10? Number of written opinions of the Court Per curiam opinions in argued cases Number of lawyers admitted to practice as of October 5, 1992: On written motion - 1 159 On oral motion.... > Total iz§!? OCTOBER TERM, 1991 Reference Index Contents: page Statistics n General in Appeals