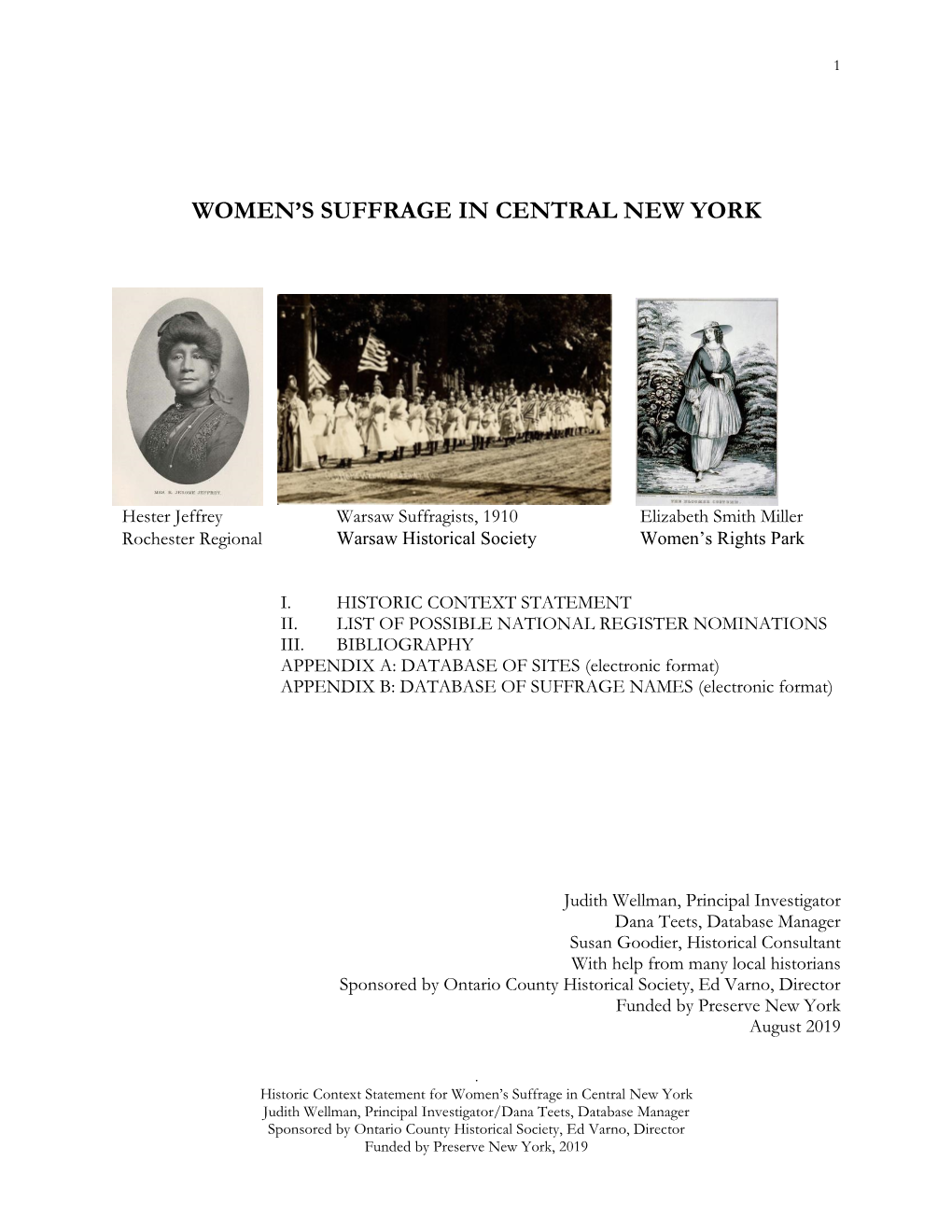

Women's Suffrage in Central New York

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Working Mothers and the Postponement of Women's

SUK_FINAL PROOF_REDLINE.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 3/13/2021 4:13 AM WORKING MOTHERS AND THE POSTPONEMENT OF WOMEN’S RIGHTS FROM THE NINETEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT JULIE C. SUK* The Nineteenth Amendment’s ratification in 1920 spawned new initiatives to advance the status of women, including the proposal of another constitutional amendment that would guarantee women equality in all legal rights, beyond the right to vote. Both the Nineteenth Amendment and the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) grew out of the long quest to enshrine women’s equal status under the law as citizens, which began in the nineteenth century. Nearly a century later, the ERA remains unfinished business with an uncertain future. Suffragists advanced different visions and strategies for women’s empowerment after they got the constitutional right to vote. They divided over the ERA. Their disagreements, this Essay argues, productively postponed the ERA, and reshaped its meaning over time to be more responsive to the challenges women faced in exercising economic and political power because they were mothers. An understanding of how and why *Professor of Sociology, Political Science, and Liberal Studies, The Graduate Center of the City University of New York, and Florence Rogatz Visiting Professor of Law (fall 2020) and Senior Research Scholar, Yale Law School. Huge thanks to Saul Cornell, Deborah Dinner, Vicki Jackson, Michael Klarman, Jill Lepore, Suzette Malveaux, Jane Manners, Sara McDougall, Paula Monopoli, Jed Shugerman, Reva Siegel, and Kirsten Swinth. Their comments and reactions to earlier iterations of this project conjured this Essay into existence. This Essay began as a presentation of disconnected chunks of research for my book, WE THE WOMEN: THE UNSTOPPABLE MOTHERS OF THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT (2020) , but the conversations generated by law school audiences nudged me to write a separate essay to explore more thoroughly how the story of suffragists’ ERA dispute after the Nineteenth Amendment affects the future of constitutional lawmaking. -

H.Doc. 108-224 Black Americans in Congress 1870-2007

“The Negroes’ Temporary Farewell” JIM CROW AND THE EXCLUSION OF AFRICAN AMERICANS FROM CONGRESS, 1887–1929 On December 5, 1887, for the first time in almost two decades, Congress convened without an African-American Member. “All the men who stood up in awkward squads to be sworn in on Monday had white faces,” noted a correspondent for the Philadelphia Record of the Members who took the oath of office on the House Floor. “The negro is not only out of Congress, he is practically out of politics.”1 Though three black men served in the next Congress (51st, 1889–1891), the number of African Americans serving on Capitol Hill diminished significantly as the congressional focus on racial equality faded. Only five African Americans were elected to the House in the next decade: Henry Cheatham and George White of North Carolina, Thomas Miller and George Murray of South Carolina, and John M. Langston of Virginia. But despite their isolation, these men sought to represent the interests of all African Americans. Like their predecessors, they confronted violent and contested elections, difficulty procuring desirable committee assignments, and an inability to pass their legislative initiatives. Moreover, these black Members faced further impediments in the form of legalized segregation and disfranchisement, general disinterest in progressive racial legislation, and the increasing power of southern conservatives in Congress. John M. Langston took his seat in Congress after contesting the election results in his district. One of the first African Americans in the nation elected to public office, he was clerk of the Brownhelm (Ohio) Townshipn i 1855. -

The Writings, Reforms, and Lectures of Frances Wright

Constructing the Past Volume 8 Issue 1 Article 7 Spring 2007 A Courage Untempered by Prudence : The Writings, Reforms, and Lectures of Frances Wright Erin Crawley Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing Recommended Citation Crawley, Erin (2007) "A Courage Untempered by Prudence : The Writings, Reforms, and Lectures of Frances Wright," Constructing the Past: Vol. 8 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing/vol8/iss1/7 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by editorial board of the Undergraduate Economic Review and the Economics Department at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. A Courage Untempered by Prudence : The Writings, Reforms, and Lectures of Frances Wright Abstract Wright was careful in her approach to slavery, saying it “is not for a young and inexperienced foreigner to suggest remedies for an evil which has engaged the attention of native philanthropists and statesmen and hitherto baffled their efforts.” This changed and eventually she would have no problem asserting her views as well as the accompanying remedies, as is evidenced in Nashoba. -

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American Culture, 1830-1900 Ana Lucette Stevenson BComm (dist.), BA (HonsI) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics I Abstract During the 1830s, Sarah Grimké, the abolitionist and women’s rights reformer from South Carolina, stated: “It was when my soul was deeply moved at the wrongs of the slave that I first perceived distinctly the subject condition of women.” This rhetorical comparison between women and slaves – the woman-slave analogy – emerged in Europe during the seventeenth century, but gained peculiar significance in the United States during the nineteenth century. This rhetoric was inspired by the Revolutionary Era language of liberty versus tyranny, and discourses of slavery gained prominence in the reform culture that was dominated by the American antislavery movement and shared among the sisterhood of reforms. The woman-slave analogy functioned on the idea that the position of women was no better – nor any freer – than slaves. It was used to critique the exclusion of women from a national body politic based on the concept that “all men are created equal.” From the 1830s onwards, this analogy came to permeate the rhetorical practices of social reformers, especially those involved in the antislavery, women’s rights, dress reform, suffrage and labour movements. Sarah’s sister, Angelina, asked: “Can you not see that women could do, and would do a hundred times more for the slave if she were not fettered?” My thesis explores manifestations of the woman-slave analogy through the themes of marriage, fashion, politics, labour, and sex. -

Central New York State Women's Suffrage Timeline

Central New York State WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE TIMELINE Photo – courtesy of http://humanitiesny.org TIMELINE OF EVENTS IN SECURING WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE IN CENTRAL NEW YORK STATE A. Some New York State developments prior to the July 1848 Seneca Falls Convention B. The Seneca Falls Convention C. Events 1850 – 1875 and 1860s New York State Map D. Events 1875 – 1893 Symbols E 1-2. Women’s Suffrage and the Erie Canal. Events around F-1. 1894 Ithaca Convention Ithaca, New York F-2. 1894 Ithaca Convention (continued) Curiosities G. Events 1895 – 1900 H. Events 1900 – 1915 I. Events 1915 – 1917 – Final Steps to Full Women’s Suffrage in New York J. Events Following Women’s Suffrage in New York 1918 – 1925 K. Resources New York State Pioneer Feminists: Elizabeth Cady Stanton & Susan Brownell Anthony. Photo – courtesy of http://www.assembly.state.ny.us A. SOME NEW YORK STATE DEVELOPMENTS PRIOR TO THE JULY 1848 SENECA FALLS CONVENTION • 1846 – New York State constitutional convention received petitions from at least three different counties Abigail Bush did NOT calling for women’s right to vote. attend the Seneca Falls convention. Lucretia Mott 1846 – Samuel J. May, Louisa May Alcott’s uncle, and a Unitarian minister and radical abolitionist from • was the featured speaker Syracuse, New York, vigorously supported Women’s Suffrage in a sermon that was later widely at the Seneca Falls circulated. convention. • April, 1848 – Married Women’s Property Act Passed. • May, 1848 – Liberty Party convention in Rochester, New York approved a resolution calling for “universal suffrage in its broadest sense, including women as well as men.” • Summer 1848 – Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Staton, and Matilda Joslyn Gage were all inspired in their suffrage efforts by the clan mothers of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Nation of New York State. -

Selected Highlights of Women's History

Selected Highlights of Women’s History United States & Connecticut 1773 to 2015 The Permanent Commission on the Status of Women omen have made many contributions, large and Wsmall, to the history of our state and our nation. Although their accomplishments are too often left un- recorded, women deserve to take their rightful place in the annals of achievement in politics, science and inven- Our tion, medicine, the armed forces, the arts, athletics, and h philanthropy. 40t While this is by no means a complete history, this book attempts to remedy the obscurity to which too many Year women have been relegated. It presents highlights of Connecticut women’s achievements since 1773, and in- cludes entries from notable moments in women’s history nationally. With this edition, as the PCSW celebrates the 40th anniversary of its founding in 1973, we invite you to explore the many ways women have shaped, and continue to shape, our state. Edited and designed by Christine Palm, Communications Director This project was originally created under the direction of Barbara Potopowitz with assistance from Christa Allard. It was updated on the following dates by PCSW’s interns: January, 2003 by Melissa Griswold, Salem College February, 2004 by Nicole Graf, University of Connecticut February, 2005 by Sarah Hoyle, Trinity College November, 2005 by Elizabeth Silverio, St. Joseph’s College July, 2006 by Allison Bloom, Vassar College August, 2007 by Michelle Hodge, Smith College January, 2013 by Andrea Sanders, University of Connecticut Information contained in this book was culled from many sources, including (but not limited to): The Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame, the U.S. -

MILITANT ABOLITIONIST GERRIT SMITH }Udtn-1 M

MILITANT ABOLITIONIST GERRIT SMITH }UDtn-1 M. GORDON·OMELKA Great wealth never precluded men from committing themselves to redressing what they considered moral wrongs within American society. Great wealth allowed men the time and money to devote themselves absolutely to their passionate causes. During America's antebellum period, various social and political concerns attracted wealthy men's attentions; for example, temperance advocates, a popular cause during this era, considered alcohol a sin to be abolished. One outrageous evil, southern slavery, tightly concentrated many men's political attentions, both for and against slavery. and produced some intriguing, radical rhetoric and actions; foremost among these reform movements stood abolitionism, possibly one of the greatest reform movements of this era. Among abolitionists, slavery prompted various modes of action, from moderate, to radical, to militant methods. The moderate approach tended to favor gradualism, which assumed the inevitability of society's progress toward the abolition of slavery. Radical abolitionists regarded slavery as an unmitigated evil to be ended unconditionally, immediately, and without any compensation to slaveholders. Preferring direct, political action to publicize slavery's iniquities, radical abolitionists demanded a personal commitment to the movement as a way to effect abolition of slavery. Some militant abolitionists, however, pushed their personal commitment to the extreme. Perceiving politics as a hopelessly ineffective method to end slavery, this fringe group of abolitionists endorsed violence as the only way to eradicate slavery. 1 One abolitionist, Gerrit Smith, a wealthy landowner, lived in Peterboro, New York. As a young man, he inherited from his father hundreds of thousands of acres, and in the 1830s, Smith reportedly earned between $50,000 and $80,000 annually on speculative leasing investments. -

Guide to Women's History Resources at the American Heritage Center

GUIDE TO WOMEN'S HISTORY RESOURCES AT THE AMERICAN HERITAGE CENTER "'You know out in Wyoming we have had woman suffrage for fifty years and there is no such thing as an anti-suffrage man in our state -- much less a woman.'" Grace Raymond Hebard, quoted in the New York Tribune, May 2, 1920. Compiled By Jennifer King, Mark L. Shelstad, Carol Bowers, and D. C. Thompson 2006 Edited By Robyn Goforth (2009), Tyler Eastman (2012) PREFACE The American Heritage Center holdings include a wealth of material on women's issues as well as numerous collections from women who gained prominence in national and regional affairs. The AHC, part of the University of Wyoming (the only university in the "Equality State") continues a long tradition of collecting significant materials in these areas. The first great collector of materials at the University, Dr. Grace Raymond Hebard, was herself an important figure in the national suffrage movement, as materials in her collection indicate. Hebard's successors continued such accessions, even at times when many other repositories were focusing their attentions on "the great men." For instance, they collected diaries of Oregon Trail travelers and accounts of life when Wyoming was even more of a frontier than it is today. Another woman, Lola Homsher, was the first formally designated University archivist and her efforts to gain materials from and about women accelerated during the service of Dean Krakel, Dr. Gene Gressley, and present director Dr. Michael Devine. As a result of this work, the AHC collections now contain the papers of pioneering women in the fields of journalism, film, environmental activism, literature, and politics, among other endeavors. -

View of the Many Ways in Which the Ohio Move Ment Paralled the National Movement in Each of the Phases

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While tf.; most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted you will find a target note listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in "sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

The 19Th Amendment

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Women Making History: The 19th Amendment Women The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. —19th Amendment to the United States Constitution In 1920, after decades of tireless activism by countless determined suffragists, American women were finally guaranteed the right to vote. The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. It was ratified by the states on August 18, 1920 and certified as an amendment to the US Constitution on August 26, 1920. Developed in partnership with the National Park Service, this publication weaves together multiple stories about the quest for women’s suffrage across the country, including those who opposed it, the role of allies and other civil rights movements, who was left behind, and how the battle differed in communities across the United States. Explore the complex history and pivotal moments that led to ratification of the 19th Amendment as well as the places where that history happened and its continued impact today. 0-31857-0 Cover Barcode-Arial.pdf 1 2/17/20 1:58 PM $14.95 ISBN 978-1-68184-267-7 51495 9 781681 842677 The National Park Service is a bureau within the Department Front cover: League of Women Voters poster, 1920. of the Interior. It preserves unimpaired the natural and Back cover: Mary B. Talbert, ca. 1901. cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work future generations. -

Restoring the Right to Vote | 2 Criminal Disenfranchisement Laws Across the U.S

R E S T O R I N G T H E RIGHT TO VOTE Erika Wood Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE The Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law is a non-partisan public policy and law institute that focuses on fundamental issues of democracy and justice. Our work ranges from voting rights to redistricting reform, from access to the courts to presidential power in the fight against terrorism. A singular institution – part think tank, part public interest law firm, part advocacy group – the Brennan Center combines scholarship, legislative and legal advo- cacy, and communications to win meaningful, measurable change in the public sector. ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER’S RIGHT TO VOTE PROJECT The Right to Vote Project leads a nationwide campaign to restore voting rights to people with criminal convictions. Brennan Center staff counsels policymakers and advocates, provides legal and constitutional analysis, drafts legislation and regulations, engages in litigation challenging disenfranchising laws, surveys the implementation of existing laws, and promotes the restoration of voting rights through public outreach and education. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Erika Wood is the Deputy Director of the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice where she lead’s the Right to Vote Project, a national campaign to restore voting rights to people with criminal records, and works on redistricting reform as part of the Center’s Government Accountability Project. Ms. Wood is an Adjunct Professor at NYU Law School where she teaches the Brennan Center Public Policy Advocacy Clinic. -

Catherine Blaine

Catherine Blaine http://columbia.washingtonhistory.org/lessons/blaineMSHS.aspx SEARCH: Home Visit Us Get Involved Education Research WA Collections Heritage Services The Society The Journey of Catharine Paine Blaine FOR MIDDLE/HIGH SCHOOL Summary: Women played a vital role in the settlement of the West, both in the creation of frontier towns and in promoting political ideals. Many of the women who settled in the West brought with them ideals that they had learned at home in the East Coast. Reform movements that had begun back East often took root in the territories in which these women came to live. This lesson plan examines the life of Catharine Paine Blaine, missionary, schoolteacher, and women’s rights activist who traveled from Seneca Falls, New York to Washington Territory in the 1850s. Students will examine primary sources and make connections to their own experiences, mapping the route that the Blaines took to reach Seattle from Seneca Falls. Using everyday items that Catharine brought with her to the Pacific Northwest, your students will explore how eastern settlers brought both objects and ideas with them as they traveled. Essential Academic Learning Requirements (EALRs): This lesson plan satisfies Washington state standards in Social Studies, Civics, Reading, Writing, and Art. It may also be used to fulfill a Dig Deep Classroom-Based Assessment. This lesson plan also meets New York state’s Social Studies standards 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 3.2, 5.1, and 5.3. Essential Questions for Students: What did Catharine experience when she traveled from New York to Washington Territory? What dangers did women settlers face when moving west? How can people change the places in which they live? What kind of change did Catharine Paine Blaine bring to the Pacific Northwest? What is a reform movement? How did eastern ideas change the lives of people in the West? What were some of the specific problems that American reformers wanted to solve in the late-19th century? Primary Sources for Student Understanding: 1.