Rats of Tobruk”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dates to Remember APRIL 2019 1-5 Year 12 Exams

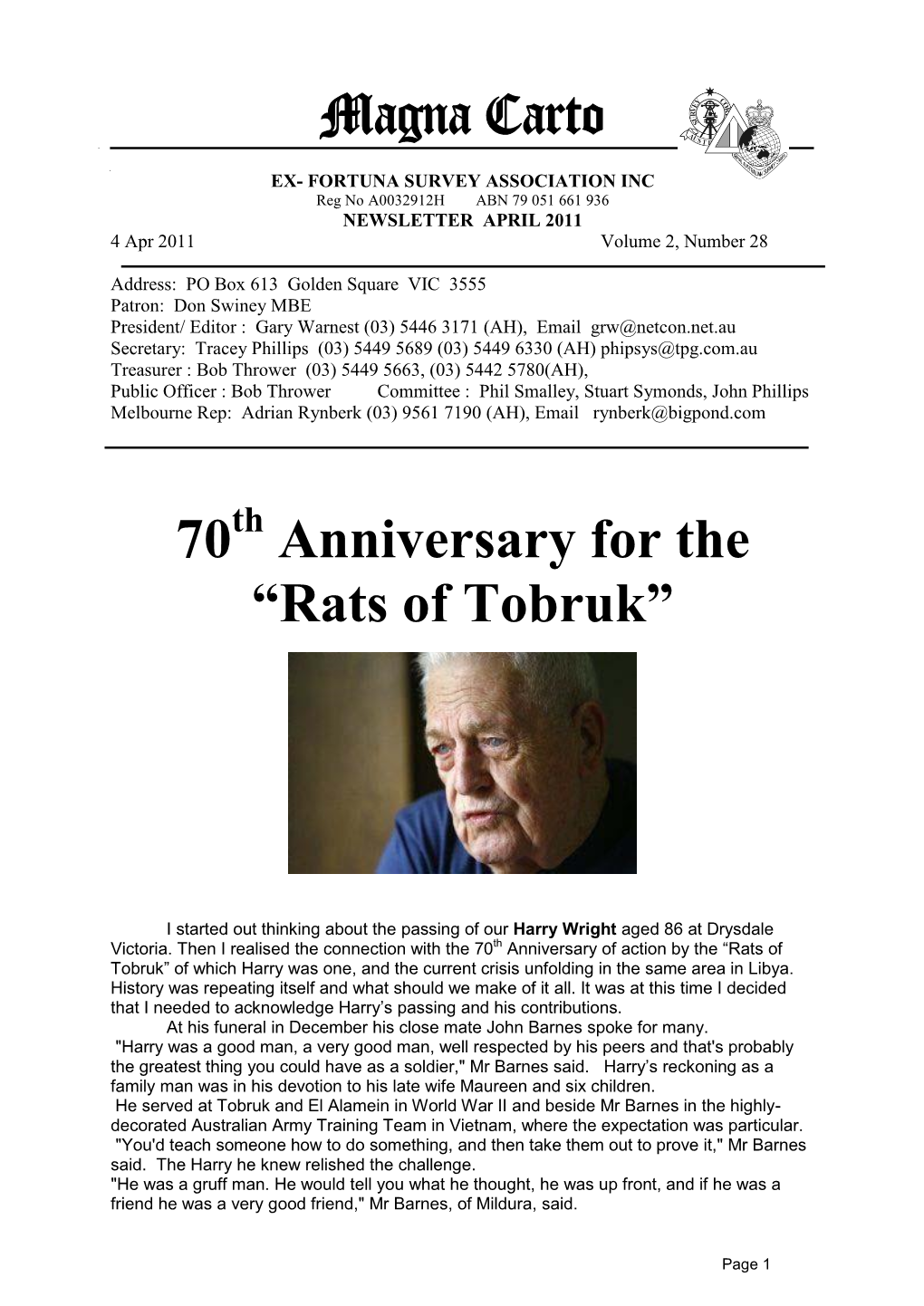

Dates to remember APRIL 2019 1-5 Year 12 exams 2 Rats of Tobruk Service May I take this opportunity to wish everyone a Happy Easter. I pray that this year’s Easter will bring you new 5 Industry Placement finishes faith, new hope and new goals – “May the joy of the Risen 19 Good Friday Christ be yours”. 21 Easter Saturday I invite you all to take time 22 Easter Sunday in your very hectic lives to take the opportunity to 25 Anzac Day attend one the many Masses that are being offered throughout our local parish churches 26 Reports uploaded during Holy Week, the Easter Vigil on Saturday 26 ECSI survey closes night or the Easter Sunday Mass of the MAY 2019 Resurrection of the Lord. It is a time of renewal and awakening for all. I would also like to wish our community a safe and happy holiday. 1-3 Year 11 Hamilton Island Camp 1-3 Year 12 QCS preparation I remind parents and students, that the first day of Term 2 is Tuesday 23 April. 6 Labour Day Holiday ATAR 2019 7-9 Year 12 Indigenous Camp I am very happy with the progress that students and teachers have made in the 10 Rice House Day transition to The Australian Tertiary Admission Rank (ATAR). There can be no 15 School Photograph Day doubt that the new system promises to be very fair to all students. If anyone has any queries or concerns, please do not hesitate to contact me personally. 16 Parent Teacher Interviews 17-19 CEY Pilgrimage Diocesan Principals’ Conference Last week, myself and Mr Geoghegan took part in the Diocesan Leadership NEW PHONE NUMBER Conference which was held in the Kevin Castles Centre in Rockhampton. -

12 Werona Street Email:[email protected] Sunnybank Qld 4109 Dear Old Boys

September 2020 Dan McErlean Bryan McSweeney 12 Werona Street email:[email protected] Sunnybank Qld 4109 Dear Old Boys The timing of the next meeting of the Brisbane Sub-Branch of the Toowoomba (St Mary’s) Brothers Old Boys’ Association has still not been decided as we wait for further advice on the current COVID-19 health warnings. News from the College is that our Principal Michael Newman has been appointed Principal of Ashgrove Marist Brothers Boarding and Day College for Boys and will be farewelled from St Mary’s College on the 18th September 2020. His replacement in 2021 will be Mr Brendan Stewart currently the Deputy Principal of St Ignatius Park College, Townsville. For the final term in 2020 Mr Stephen Monk our Deputy Principal will act as St Mary’s College Principal. Please remember in your prayers Old Boys & Friends of the College recently deceased; Rev Fr Tom Keegan, former P.P. of Holy Name Parish. Brian Bianchi (year 1980) husband of Andrea (Meehan), son of Darcy (RIP) and Clare, son-in-law of Shirley & Jim Meehan father & father-in-law of Josh & Jade, Emily, Luke & Nadine. Life Member Kerry Taylor (1950-1956) husband of Carol, father of Michelle and Christopher. John Bagget (1945-1954) husband of Janet, father of Sue, Paula and Karen, brother of Bill (dec), Joe (dec) and Paul. Cecil Hogan (91 years) husband of Marjory and brother of Jack & Darcy (both dec). Daphne (Martin) Quinn, wife of John (dec) mother of Elizabeth and Margaret, sister of Mavis, Brian and Nancy. Anne Mary (Hede) Wilson, wife of Life Member John, mother and mother-in-law of Christopher, Elizabeth and Kent, and David, sister of Dr John, Andrew, Damien and Paul. -

April 2008 VOL

Registered by AUSTRALIA POST NO. PP607128/00001 THE april 2008 VOL. 31 no.2 The official journal of The ReTuRned & SeRviceS League of austraLia POSTAGE PAID SURFACE ListeningListening Branch incorporated • Po Box 3023 adelaide Tce, Perth 6832 • established 1920 PostPostAUSTRALIA MAIL ANZAC Day In recognition of the great sacrifice made by the men and women of our armed forces. 2008ANZAC DAY 2008 Trinity Church SALUTING DAIS EX-SERVICE CONTINGENTS VIP PARKING DAIS 2 JEEPS/HOSPITAL CARS JEEPS/HOSPITAL ADF CONTINGENTS GUEST PARKING ANZAC Day March Forming Up Guide Page 14-15 The Victoria Cross (VC) Page 12, 13 & 16 A Gift from Turkey Page 27 ANZAC Parade details included in this Edition of Listening Post Rick Hart - Proudly supporting your local RSL Osborne Park 9445 5000 Midland 9267 9700 Belmont 9477 4444 O’Connor 9337 7822 Claremont 9284 3699 East Vic Park Superstore 9470 4949 Joondalup 9301 4833 Perth City Mega Store 9227 4100 Mandurah 9535 1246 RSL Members receive special pricing. “We won’t be beaten on price. Just show your membership card! I put my name on it.” 2 The Listening Post april 2008 www.northsidenissan.com.au ☎ 9409 0000 14 BERRIMAN DRIVE, WANGARA ALL NEW MICRA ALL NEW DUALIS 5 DOOR IS 2 CARS IN 1! • IN 10 VIBRANT COLOURS • HATCH AGILITY • MAKE SURE YOU WASH • SUV VERSATILITY SEPARATELY • SLEEK - STYLISH DUALIS FROM FROM $ * DRIVE $ * DRIVE 14,990 AWAY 25,990 AWAY * Metallic Paint Extra. Manual Transmission. $ * DRIVE $ * DRIVE 15576 AWAY 38909 AWAY Metallic paint (as depicted) $300 extra. TIIDA ST NAVARA ST-X SEDAN OR HATCH MANUAL TURBO DIESEL MANUAL • 6 speed manual transmission • Air conditioning • CD player • 126kW of power/403nm torque • 3000kg towing capacity • Remote keyless entry • Dual SRS airbags • ABS brakes • Alloy wheels • ABS brakes • Dual airbags $ * DRIVE $ * DRIVE 43888 AWAY 44265 AWAY NOW WITH ABS BRAKES FREE BULL BAR, TOW BAR FREE & SPOTTIES $ 1000 FUEL Metallic paint (as depicted) $300 extra. -

The Story of Tobruk House

The Story of Tobruk House A Dream, which through determination and hard work, turned into reality. „At precisely 3:55 pm, on Saturday, 29th September 1956, Lt-Gen. Sir James Leslie Morshead, alias “Ming the Terrible”, alias “Rat Number One”, turned the specially inscribed gold key to open the door of TOBRUK HOUSE‟ 1 What if these walls could talk, what a story they would tell! (This story is in mainly based on information contained in articles published in various editions of the Tobruk Echo and its successor the Tobruk House News.) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ The first General Meeting of ROTA Melbourne Branch, was held at Tobruk House on 28th March 1956.2 This was the start of a tradition that continues to this day, with the current General Meetings being normally held monthly on the fourth Friday of the Month. However the story starts before the 28th March 1956. The Victorian Branch of the Rats of Tobruk Association was formed on the 2nd October 1945. A few years after this, the then Members decided that they wanted „a place of their own – to eat, sleep, drink, play, relax, and being a multi level building comprising:- Top Floor. Sleeping Quarters, Showers, Bathrooms, etc. Third Floor. Bar, Dining Room, Card Room. Second Floor. Library, Meeting Room and Billiards. First Floor. Office, Lounge, Reading Room. Ground Floor. Large hall for Dancing, Memorial and Remembrance Services, Concerts. Basement. Car Park3 Page 1 of 6 If this was being planned today, there is no doubt that a floor to be filled with poker machines would have been included. -

The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918"

5/05/2017 #NAME? Item Title Volume 1 "The Official History of Australia in the War of 11914-1918".I 2 "The Official History of Australia in the War of 21914-1918".II 3 "The Official History of Australia in the War of 31914-1918".III 4 "The Official History of Australia in the War of 41914-1918".IV 5 "The Official History of Australia in the War of 51914-1918".V 6 "The Official History of Australia in the War of 61914-1918".IV – The Australian Imperial Force in France, 1917 7 "The Official History of Australia in the War of 71914-1918".VII 8 "The Official History of Australia in the War of 81914-1918".VIII The Australian Flying Corps 9 "The Official History of Australia in the War of 91914-1918".IX 10 "The Official History of Australia in the War of10 1914-1918".X 11 "The Official History of Australia in the War of11 1914-1918".XI 12 "The Official History of Australia in the War of12 1914-1918".XII 390 "Tin Shed " Days 306 100 years of Austrlians atpaper war 49 2/14 Australian Infantry Battalion 166 200 Shots: Damien Parer and George Silk with the Australians at War in New Guinea 224 2194 days of war 87 A Bridge to Far 129 A Time of War 204 A Voyage with an Australian Sailer 327 A world at war: aglobal history of World War II 162 Above the Trenches: A Complete Record of the Fighter Aces and Units of the British Empire Air Forces 1915-1920, Volume 1 22 Active Service 1941, 185 Adolf Hitler 274 Advance: Official Journel Highett Sub- Branch RSS&AILAVolume 1 No1 September 1960 213 Age shall not weary them 110 Air War Pacific: The Fight for Supremacy in the Far East, 1937 to 1945 152 Air warfare 287 Aircraft Carriers 148 Aircraft Carriers: fron 1914 to present 459 AIRCRAFT W/T Operation Handbook Air Board RAAF Publication 122 October 1940 196 All hands on Deck 219 All the King's Enimies: A History of the 2/5th Australian Infantry Battalion 1939-1945 74 ALMANACCO R. -

BATTLE for AUSTRALIA NEWSLETTER a PROUD SUPPORTER of the RAAMC ASSOCIATION Inc

Semper Paratus 5 FIELD AMBULANCE RAAMC ASSOCIATION Established 1982 SPRING ISSUE 2019 BATTLE FOR AUSTRALIA NEWSLETTER A PROUD SUPPORTER OF THE RAAMC ASSOCIATION Inc. WEB SITE: www.raamc.org.au 2 5 Field Ambulance RAAMC Association Patron: COL Ray Hyslop OAM RFD Office Bearers PRESIDENT: LTCOL Derek Cannon RFD– 31 Southee Road, Richmond NSW 2753 (M) 0415 128 908 HON SECRETARY: Alan Curry OAM—35/1a Gordon Close, Anna Bay NSW 2316 (H) (02)4982.2189 (M) 0427 824 646 Email: [email protected] HON TREASURER: Brian Tams—453/1 Scaysbrook Drive, Kincumber NSW 2251 (H) (02) 4368 6161 COMMITTEE: WO 1 Warren Barnes OAM Mobile: 0409 909 439 Fred Bell (ASM) Mobile: 0410 939 583 Barry Collins OAM Phone: (02) 9398 6448 Ron Foley Mobile: 0422 376 541 Ann Jackson Mobile: 0407 236 724 CONTENTS VALE (Reg Lawrence, Garry Flood, Peter Paisley) -------------------------------------------- Pages 3-5 POEM --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Page 5 LIFE MEMBERS ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Page 6 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE/POEM/SICK PARADE ---------------------------------------------------- Page 7 SECRETARY’S MESSAGE/POEM/Story/KIND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS -------------------- Page 8 ITEMS OF INTEREST ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Pages 9-13 POEM/Story ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Page 14 MESSAGES FROM -

CHS84-Rats-Of-Tobruk-Association

QUEEN VICTORIA MUSEUM AND ART GALLERY CHS 84 RATS OF TOBRUK ASSOCIATION, NORTHERN SUB-BRANCH COLLECTION War Veterans, Northern Tasmania INTRODUCTION THE RECORDS 1.Legal Records 2.Minutes of Meetings 3.Correspondence 4.Annual Reports 5.Financial Records 6.Miscellaneous Items OTHER SOURCES INTRODUCTION The Rats of Tobruk Association, Northern Sub-branch, was established in 1946, following the formation of the Rats of Tobruk Association in Tasmania in July 1945. Material in the collection dates from 1964. Regular monthly meetings were held by the Northern Sub-branch at the RSL Headquarters, Anzac Hostel/House in Paterson Street, from at least 1972 until 1990, then for some months at the Newstead Hotel before moving to Kings Meadows Hotel, and finally to Anzac House, Wellington Street. An annual Tobruk luncheon and pre Christmas function at the Longford RSL Club were held. The Sub-branch was represented at community activities associated with ex-service personnel, particularly at Cenotaph commemorations and a close association was maintained with the Department of Veterans Affairs. Schools were also visited. For some years the Rats Review, published by the Tasmanian Rats of Tobruk Association from 1948, was edited by a member of the Northern Sub-branch. In the late 1990s meetings were held every three months, with members enjoying monthly counter lunches at various hotels during the intervening months. The Rats of Tobruk Association world convention and reunion was held in Launceston in 1989. That year the Northern Sub-branch established the Tobruk Bursary to be awarded to a boy and girl in their final primary school year who contributed in some worthy way to the general welfare of the school. -

Australian Memory and the Second World War

Journal of Military and Strategic VOLUME 14, ISSUE 1, FALL 2011 Studies The Second War in Every Respect: Australian memory and the Second World War Joan Beaumont The Second World War stands across the 20th century like a colossus. Its death toll, geographical spread, social dislocation and genocidal slaughter were unprecedented. It was literally a world war, devastating Europe, China and Japan, triggering massive movements of population, and unleashing forces of nationalism in Asia and Africa that presaged the end of European colonialism. The international order was changed irrevocably, most notably in the rise of the two superpowers and the decline of Great Britain. For Australia too, though the loss of life in the conflict was comparatively small, the war had a profound impact. The white population faced for the first time the threat of invasion, with Australian territory being bombed from the air and sea in 1942.1 The economy and society were mobilized to an unprecedented degree, with 993,000 men and women, of a population of nearly seven million, serving in the military forces. Nearly 40,000 of these were killed in action, died of wounds or died while prisoners of war.2 Gender roles, family life and social mores were changed with the mobilization of women into the industrial workforce and the friendly invasion of possibly a million 1 The heaviest raid was on the northern city of Darwin on 19 February 1942. Other towns in the north of Western Australia and Queensland were bombed across 1942; while on 31 May 1942 three Japanese midget submarines entered Sydney Harbour and shelled the suburbs. -

Book a Facilitated Program for 2011 and We Will Provide a Much Deeper

EDUCATION SERVICES 2 011 Tobruk Ray Ewers and George Browning, 1954-56 AWM ART41035 Book a facilitated program for 2011 and we will provide a much deeper learning experience. RelAWM31948.004 Tobruk 1941 – A Gallant Information For Teachers and Tenacious Defence Book a facilitated program for your school group; a program will provide a much deeper learning experience. New programs, aligned to the Australian The whole empire is watching your steadfast and Curriculum for History, are now available. spirited defence … with gratitude and admiration. Prime Minister Winston Churchill The Australian War Memorial provides a wide range of REL07652 Teacher’s checklist educational programs aligned with the new Australian Curriculum for History. These programs are designed to Log on to www.awm.gov.au/education and read about the Memorial’s curriculum-based programs and choose The fate of the war in North Africa hung on the possession protect it ran in a rough semicircle across the desert suit your classroom and curriculum needs. which program best suits the needs of your students. of a small harbour town in the far corner of the Libyan desert from coast to coast, and consisted of dozens of concrete- When you visit the Memorial, and book a facilitated – Tobruk. It was vital for the Allies’ defence of Egypt and the sided strong-points protected by barbed-wire fences and program, students gain a much deeper learning Book your visit online and record your booking Suez Canal to hold the town with its harbour, as this forced anti-tank ditches. experience. Our trained educators draw on personal reference number. -

The Story of My Grandfather PRIVATE KEN MCKAY WX3836

The Story of My Grandfather PRIVATE KEN MCKAY WX3836 By Melissa Zappelli Official Army Photograph of Private Kenneth McKay, WX 3836 This is the story of of my Grandfather, Ken McKay, my Dad’s Dad. When Australia joined Great Britain by declaring war on Nazi Germany in September 1939, my Grandfather was a young man enjoying the prime of his life with a beautiful wife and new born baby son. Like almost all men of the right age, he answered the call to arms and signed up to join the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), as an adventurous young soldier eager to see the world and prove himself by fighting for King and Country. It was barely a choice, yet that action would profoundly change his destiny and that of those who loved him. This is a story of courage and love, of the enduring brutality of war and the effects of tragedy on one family. It is the story of a fallen boyish hero with an impish face, pieced together from the fragmented glimpses that have survived the relentless erosion of time. A synthesis of faded memories, decaying letters, battered photographs, family stories, war history and military documentation. There is just enough to establish a sense of who my Grandfather was. It is all that we have. Copyright First Published in 2018 by Melissa Zappelli Website; www.melissazappelli.com © Melissa Zappelli 2018 The moral rights of the author have been asserted. All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the Australian Copyright Act 1968 and detailed in the disclaimer below. All inquiries should be made to the author. -

Vietnam Veterans

Latest news VIETNAM VETERANS DAY - 18TH AUGUST 2020 We have decided that due to the current COVID situation, and with no clear direction from authorities as to when all restrictions will be lifted, the service on Vietnam Veterans Day (18 August) will be cancelled. Like Anzac Day, President Alan Harcourt and David Smock (President of Vietnam Veterans Group) will lay a wreath on behalf of everyone. If any of the families of our Honour Roll personnel are attending they may lay their own wreath. As there is no organized service, the usual laying of wreaths will not be held also chairs will not be available. However, you are most welcome to pay your respects at a time suitable to you. Future Vietnam Veterans Day service will be moved to 10.00am to coincide with other celebrations around the country. This will become the norm from now on. On behalf of Suzie (the secretaries secretary) and myself please stay safe and keep well. MICHAEL MCDONNELL, LEAGUE SECRETARY excursion - toowoomba carnival of flowers It’s so nice to be back with some good news on the Vets and Wellbeing Excursions . The overnight trip to the Carnival of Flowers on 22/9/2020 is all locked in and tickets are selling fast! The trip is great value so book and pay at Redlands RSL reception - first in best dressed. See page 20 for more info. GREG SAUNDERS, CONVENOR OF SOCIAL EVENTS President’s Report Fellow members Well this is our second Bugle since the Pandemic shutdown and still no cure in sight. I hope all are avoiding the virus, you must be, as we have heard no reports. -

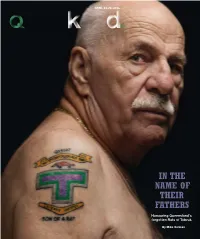

Rats of Tobruk

APRIL 21-22L 2012L IN THE NAME OF THEIR FATHERS Honouring Queensland’s forgotten Rats of Tobruk By Mike Colman BQW21APR12COV_01.indd 1 13/04/2012 01:50:42 history FOR 70 YEARS HISTORIANS TOLD THE STORY OF THE SIEGE OF TOBRUK – AND FOR 70 YEARS THEY GOT IT WRONG, STARTING WITH THE ROLE OF THE 2/15TH BATTALION. Story Mike Colman s 21-year-old Jack Anning looked across the Libyan desert in the early morning light and saw the Panzer tanks coming toward him, with elite German soldiers either riding on the tanks or fanned Aout jogging behind them, he felt no fear. “I was wildly excited,” he says. “I was sick of running. We all were. We were anxious to have a go.” It was Easter Monday, 1941, on the outskirts of Tobruk, Libya’s Mediterranean port town near the Egyptian border. Over the next few hours Anning and the rest of A Company from the all- Queensland 2/15th Battalion would indeed “have a go” at Lieutenant General Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps. In their first experience of combat they would take on one of Rommel’s favourite A job well done … commanders and his battle-hardened troops. Cpl. Jack Anning By mid-morning the fighting was all but over. towards the end of S his military service. The German commander lay dead in a ditch, BQW21APR12RAT_16-21.indd 16 13/04/2012 06:06:22 BQW21APR12RAT_16-21.indd 17 13/04/2012 06:06:37 history his body covered by a bloodied Nazi flag as his when he stepped on a “Jumping Jack” landmine form a last line of defence.