Australian Army Chaplains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chaplaincy in Anglican Schools

CHAPLAINCY IN ANGLICAN SCHOOLS GUIDELINES FOR THE CONSIDERATION OF BISHOPS, HEADS OF SCHOOLS, CHAPLAINS, AND HEADS OF THEOLOGICAL COLLEGES THE REVEREND DR TOM WALLACE ON BEHALF OF THE AUSTRALIAN ANGLICAN SCHOOLS NETWORK ANGLICAN CHURCH OFFICE 26 KING WILLIAM ROAD NORTH ADELAIDE SA 5006 AUGUST 1999 1 CHAPLAINCY IN ANGLICAN SCHOOLS GUIDELINES FOR BISHOPS, HEADS OF SCHOOLS AND CHAPLAINS 1. BACKGROUND At the National Anglican Schools Conference held at Melbourne Girls’ Grammar in April 1997 the National Anglican Schools Consultative Committee was asked to conduct a survey on Religious Education and Chaplaincy in Anglican schools in Australia. The Survey was conducted on behalf of the Committee by Dr Peter Coman, Executive Director of the Anglican Schools Office in the Diocese of Brisbane in February 1998. An Interim Report was presented to the National Conference in May 1998. The Rev’d Dr Tom Wallace of the Anglican Schools Commission in Western Australia was asked to give consideration to ways in which the Report may be followed up and a small consultative committee, representative of all the States, was appointed to work with him. It was agreed that Dr Wallace would prepare a discussion paper on Chaplaincy in Anglican Schools, which would be considered initially by members of the representative committee with a view to wider circulation to Principals, Chaplains and Diocesan Bishops. That discussion paper was prepared and feedback on it was received from several Chaplains from three Australian States. As a result of the feedback the Paper was revised with a view to it being considered at a national gathering of Chaplains at the National Anglican Schools Conference in May 1999. -

Dates to Remember APRIL 2019 1-5 Year 12 Exams

Dates to remember APRIL 2019 1-5 Year 12 exams 2 Rats of Tobruk Service May I take this opportunity to wish everyone a Happy Easter. I pray that this year’s Easter will bring you new 5 Industry Placement finishes faith, new hope and new goals – “May the joy of the Risen 19 Good Friday Christ be yours”. 21 Easter Saturday I invite you all to take time 22 Easter Sunday in your very hectic lives to take the opportunity to 25 Anzac Day attend one the many Masses that are being offered throughout our local parish churches 26 Reports uploaded during Holy Week, the Easter Vigil on Saturday 26 ECSI survey closes night or the Easter Sunday Mass of the MAY 2019 Resurrection of the Lord. It is a time of renewal and awakening for all. I would also like to wish our community a safe and happy holiday. 1-3 Year 11 Hamilton Island Camp 1-3 Year 12 QCS preparation I remind parents and students, that the first day of Term 2 is Tuesday 23 April. 6 Labour Day Holiday ATAR 2019 7-9 Year 12 Indigenous Camp I am very happy with the progress that students and teachers have made in the 10 Rice House Day transition to The Australian Tertiary Admission Rank (ATAR). There can be no 15 School Photograph Day doubt that the new system promises to be very fair to all students. If anyone has any queries or concerns, please do not hesitate to contact me personally. 16 Parent Teacher Interviews 17-19 CEY Pilgrimage Diocesan Principals’ Conference Last week, myself and Mr Geoghegan took part in the Diocesan Leadership NEW PHONE NUMBER Conference which was held in the Kevin Castles Centre in Rockhampton. -

The History of the New York State Association of Fire Chaplains, Inc

The History of the New York State Association of Fire Chaplains, Inc. Celebrating the Association’s 2016 (Updated October 7, 2017) Table of Contents SS Dorchester .............................................................................................. 3 Chaplains’ Seminar at FASNY - 1966 ......................................................... 4 Incorporation ................................................................................................ 7 Support of Fire Chiefs and FASNY .............................................................. 8 Chaplain’s Manual........................................................................................ 8 1970’s Conferences ..................................................................................... 9 Fire Academy Established ........................................................................... 9 Women in Fire Service ............................................................................... 10 1980’s Conferences ................................................................................... 10 Lay Chaplains ............................................................................................ 11 1994 - Lay Chief Chaplain ......................................................................... 12 2000’s Conferences ................................................................................... 14 FASNY Chaplains’ Committee ................................................................... 16 Marriage Renewal Service - 2006 ............................................................ -

Standards for the Work Of. the .Chaplain in the General Hospital

fillicia11y Adopted by the Am . .Ptot..estant H09P,;+~ 1 A encal1 '.B' _Lal. BSll. at th . OBton Conven~ion c_ te be Q v. ~p m r 194(}. Standards for the Work of. the .Chaplain in the General Hospital REV. RUSSELL L. DICKS, D.O. T has come to the attention of the American The Author Protestant Hospital Association that the • Rev. Russell L. Dicks, D.D., is Chaplain I spiritual needs of many patients, both in pri of the Presbyterian Hospital, Chic~go, and vate and public institutions, are not receiving Chairman of the Special Study Committee proper attention. In some instances patients are that prepared these Standards. not receiving any spiritual care, in others they are receiving altogether too much. We know of with the clergyman's ordination vows or his institutions where as many as seven or eight higher loyalties. different religious workers may speak to the same patient in a given afternoon while hundreds of In the past when treatment of the soul was other patients in the same institution receive no considered as apart from medical care of the pa ,. attention. It has also come to our attention that tient; and was believed to have nothing to do with many religious workers in hospitals attempt to his health, the hospital and the physician were force their own religious views upon the patient not greatly concerned with the spiritual condition whether he desires them or not. of the patient, although some medical men have always recognized a close alliance between body It is our hope that through the following sug and soul. -

Housing Allowance and Other Clergy Tax Issues Revised December 2015

Housing Allowance and Other Clergy Tax Issues Revised December 2015 By Dennis R. Walsh, CPA This is a summary of special income tax issues applicable to clergy employed by units of government and serving in other non-traditional settings. All information provided is intended for educational purposes. As laws are constantly changing, the reader should seek competent guidance as necessary and be aware of applicable legislative, administrative, and judicial action that may have occurred since preparation of this document. Q1: When is an individual a minister for tax purposes? Whether the services of a duly ordained, licensed, or commissioned clergyperson are classified as in the “exercise of ministry” for federal tax purposes determines if tax rules unique to clergy are applicable. o For services other than as an employee of a theological seminary or church- controlled organization, in order to be considered in the exercise of ministry the services must involve either: o The ministration of sacerdotal functions (.e.g. communion, baptism, funerals, etc.), or o The conduct of religious worship The following should also be considered: o The determination of what constitutes the performance of “sacerdotal functions” and the conduct of religious worship depends on the tenets and practices of the individual’s church. Treas. Reg. § 1.1402(c)-5(b)(2)(i). o A minister who is performing the conduct of worship and ministration of sacerdotal functions is performing service in the exercise of his/her ministry, whether or not these services are performed for a religious organization. Treas. Reg. § 1.1402(c)-5(b)(2)(iii). o The service of a chaplain in the Armed Forces is considered to be those of a commissioned officer and not in the exercise of his or her ministry. -

12 Werona Street Email:[email protected] Sunnybank Qld 4109 Dear Old Boys

September 2020 Dan McErlean Bryan McSweeney 12 Werona Street email:[email protected] Sunnybank Qld 4109 Dear Old Boys The timing of the next meeting of the Brisbane Sub-Branch of the Toowoomba (St Mary’s) Brothers Old Boys’ Association has still not been decided as we wait for further advice on the current COVID-19 health warnings. News from the College is that our Principal Michael Newman has been appointed Principal of Ashgrove Marist Brothers Boarding and Day College for Boys and will be farewelled from St Mary’s College on the 18th September 2020. His replacement in 2021 will be Mr Brendan Stewart currently the Deputy Principal of St Ignatius Park College, Townsville. For the final term in 2020 Mr Stephen Monk our Deputy Principal will act as St Mary’s College Principal. Please remember in your prayers Old Boys & Friends of the College recently deceased; Rev Fr Tom Keegan, former P.P. of Holy Name Parish. Brian Bianchi (year 1980) husband of Andrea (Meehan), son of Darcy (RIP) and Clare, son-in-law of Shirley & Jim Meehan father & father-in-law of Josh & Jade, Emily, Luke & Nadine. Life Member Kerry Taylor (1950-1956) husband of Carol, father of Michelle and Christopher. John Bagget (1945-1954) husband of Janet, father of Sue, Paula and Karen, brother of Bill (dec), Joe (dec) and Paul. Cecil Hogan (91 years) husband of Marjory and brother of Jack & Darcy (both dec). Daphne (Martin) Quinn, wife of John (dec) mother of Elizabeth and Margaret, sister of Mavis, Brian and Nancy. Anne Mary (Hede) Wilson, wife of Life Member John, mother and mother-in-law of Christopher, Elizabeth and Kent, and David, sister of Dr John, Andrew, Damien and Paul. -

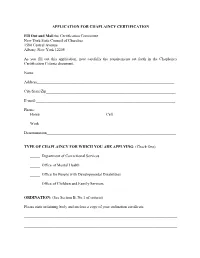

APPLICATION for CHAPLAINCY CERTIFICATION Fill out and Mail To

APPLICATION FOR CHAPLAINCY CERTIFICATION Fill Out and Mail to: Certification Committee New York State Council of Churches 1580 Central Avenue Albany, New York 12205 As you fill out this application, note carefully the requirements set forth in the Chaplaincy Certification Criteria document. Name________________________________________________________________________ Address______________________________________________________________________ City/State/Zip__________________________________________________________________ E-mail:_______________________________________________________________________ Phone: Home__________________________________Cell________________________________ Work______________________________________________________________________ Denomination__________________________________________________________________ TYPE OF CHAPLAINCY FOR WHICH YOU ARE APPLYING: (Check One) _____ Department of Correctional Services _____ Office of Mental Health _____ Office for People with Developmental Disabilities _____ Office of Children and Family Services ORDINATION: (See Section B, No.1 of criteria) Please state ordaining body and enclose a copy of your ordination certificate. ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ OFFICIAL ECCLESIASTICAL ENDORSEMENT: (Section B, No.2 of criteria) Give name of agency or official authorized by your denomination to endorse its clergy for chaplaincy positions. (This agency or person -

800 Navy Chaplains

A calling within a calling CHAPLAIN CHAPLAIN The ability to minister outside of the conventional setting. NAVY POLICY Navy Chaplains are expected to support and ensure the free The chance to interact with members of diverse faith practice of religion for all. Therefore, you must be: groups. The opportunity to make a profound difference in • Willing to function in the diverse and pluralistic environment of the military the lives of individuals on a regular basis. These are some • Tolerant of diverse religious traditions of the things that make the work of Navy Chaplains so • Respectful of the rights of individuals to determine their own religious convictions rewarding and so unique. The specialized environment of the military requires Navy Chaplains The Navy Chaplain Corps is made up of over 800 Navy Chaplains. Chaplains confirm more to embrace these guidelines without compromising the tenets of than 100 different faith groups currently represented (Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist their own religious traditions. Also, it is important to note that and many others). Each Chaplain is also a Navy Officer – meaning each holds an important Navy Chaplains are officially considered noncombatants and not leadership role. authorized to bear arms. Together, Navy Chaplains enable the free practice of religion for all the Sailors, Marines and NOTES Coast Guardsmen who serve. But their impact goes far beyond the mere exercise of religion. JOB DESCRIPTION As a Navy Chaplain, you will nurture the spiritual well-being of those around you. Living with them. Working with them. Eating with them. Praying with them. Understanding their needs and challenges like no one else – in a ministry that is truly 24/7. -

April 2008 VOL

Registered by AUSTRALIA POST NO. PP607128/00001 THE april 2008 VOL. 31 no.2 The official journal of The ReTuRned & SeRviceS League of austraLia POSTAGE PAID SURFACE ListeningListening Branch incorporated • Po Box 3023 adelaide Tce, Perth 6832 • established 1920 PostPostAUSTRALIA MAIL ANZAC Day In recognition of the great sacrifice made by the men and women of our armed forces. 2008ANZAC DAY 2008 Trinity Church SALUTING DAIS EX-SERVICE CONTINGENTS VIP PARKING DAIS 2 JEEPS/HOSPITAL CARS JEEPS/HOSPITAL ADF CONTINGENTS GUEST PARKING ANZAC Day March Forming Up Guide Page 14-15 The Victoria Cross (VC) Page 12, 13 & 16 A Gift from Turkey Page 27 ANZAC Parade details included in this Edition of Listening Post Rick Hart - Proudly supporting your local RSL Osborne Park 9445 5000 Midland 9267 9700 Belmont 9477 4444 O’Connor 9337 7822 Claremont 9284 3699 East Vic Park Superstore 9470 4949 Joondalup 9301 4833 Perth City Mega Store 9227 4100 Mandurah 9535 1246 RSL Members receive special pricing. “We won’t be beaten on price. Just show your membership card! I put my name on it.” 2 The Listening Post april 2008 www.northsidenissan.com.au ☎ 9409 0000 14 BERRIMAN DRIVE, WANGARA ALL NEW MICRA ALL NEW DUALIS 5 DOOR IS 2 CARS IN 1! • IN 10 VIBRANT COLOURS • HATCH AGILITY • MAKE SURE YOU WASH • SUV VERSATILITY SEPARATELY • SLEEK - STYLISH DUALIS FROM FROM $ * DRIVE $ * DRIVE 14,990 AWAY 25,990 AWAY * Metallic Paint Extra. Manual Transmission. $ * DRIVE $ * DRIVE 15576 AWAY 38909 AWAY Metallic paint (as depicted) $300 extra. TIIDA ST NAVARA ST-X SEDAN OR HATCH MANUAL TURBO DIESEL MANUAL • 6 speed manual transmission • Air conditioning • CD player • 126kW of power/403nm torque • 3000kg towing capacity • Remote keyless entry • Dual SRS airbags • ABS brakes • Alloy wheels • ABS brakes • Dual airbags $ * DRIVE $ * DRIVE 43888 AWAY 44265 AWAY NOW WITH ABS BRAKES FREE BULL BAR, TOW BAR FREE & SPOTTIES $ 1000 FUEL Metallic paint (as depicted) $300 extra. -

The Story of Tobruk House

The Story of Tobruk House A Dream, which through determination and hard work, turned into reality. „At precisely 3:55 pm, on Saturday, 29th September 1956, Lt-Gen. Sir James Leslie Morshead, alias “Ming the Terrible”, alias “Rat Number One”, turned the specially inscribed gold key to open the door of TOBRUK HOUSE‟ 1 What if these walls could talk, what a story they would tell! (This story is in mainly based on information contained in articles published in various editions of the Tobruk Echo and its successor the Tobruk House News.) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ The first General Meeting of ROTA Melbourne Branch, was held at Tobruk House on 28th March 1956.2 This was the start of a tradition that continues to this day, with the current General Meetings being normally held monthly on the fourth Friday of the Month. However the story starts before the 28th March 1956. The Victorian Branch of the Rats of Tobruk Association was formed on the 2nd October 1945. A few years after this, the then Members decided that they wanted „a place of their own – to eat, sleep, drink, play, relax, and being a multi level building comprising:- Top Floor. Sleeping Quarters, Showers, Bathrooms, etc. Third Floor. Bar, Dining Room, Card Room. Second Floor. Library, Meeting Room and Billiards. First Floor. Office, Lounge, Reading Room. Ground Floor. Large hall for Dancing, Memorial and Remembrance Services, Concerts. Basement. Car Park3 Page 1 of 6 If this was being planned today, there is no doubt that a floor to be filled with poker machines would have been included. -

Chaplains in Canon Law and Contemporary Practice

C A N O N L A W CHAPLAINS IN CANON LAW AND CONTEMPORARY PRACTICE anon law defines a chaplain as “a priest to whom is entrusted in a stable manner the pastoral care, at least in part, of some community or special group of Christ’s faithful, C to be exercised in accordance with universal and particular law” (Canon 564). The law establishes the chaplain as a canonical figure in the person of a priest who is account- able to the diocesan bishop. A deacon cannot be named a chaplain in the canonical sense. “Stable manner” implies the Consultation between the local ordinary formal appointment to a par- and a religious superior in a house of a lay reli- ticular group associated with gious institute before appointing a chaplain for various apostolates such as the purpose of directing liturgical functions (567 educational institutions or ser- gives the superior the right to propose a particu- vices with long-standing social lar priest) traditions such as prisons or Appointment of chaplains for those who are hospitals. The office is no lon- not able to avail themselves of the ordinary care SR. MARLENE ger linked to foundations or of parish priests, e.g. migrants, exiles, fugitives, WEISENBECK non-parochial churches as was nomads, seafarers (568) and armed forces (569) the practice in the past. “Pas- which must take into account state relationships toral care” refers to the role of with armed forces the priest having a canonical office for full care Circumstances in which a non-parochial of souls, which includes preaching, sacramental church is attached to a center of a community or minister of baptism, penance, anointing of the group (570) sick, marriage, Eucharist and celebration of the The requirement of the chaplain to maintain Mass. -

Finding the Balance in Chaplain Roles As Both Clergy and Military Officers

Volume 89 • Number 2 • Summer 2016 Finding the balance in chaplain roles as both clergy and military officers “Voices of Chaplaincy” Book Series – Your Stories Needed The Military Chaplains Association is seeking short, personal stories of chaplain ministry from MCA members in the core ministry functions of nurturing the living, caring for the wounded, and honoring the fallen. Help the MCA share and preserve the inspirational stories of chaplains who served or currently serve in the U.S. Armed Forces, Civil Air Patrol and VA Chaplain Service. Stories will be compiled, edited and published by MCA in paperback and e-book format and made available for worldwide distribution. All proceeds from book sales will benefit the MCA Chaplain Candidate Scholarship Fund. This new book series will expand the ability of the MCA to mentor and connect chaplains as we tell our story as personal advocates and voices of chaplaincy. Stories should be limited to 500-1000 words (2-3 double-spaced pages) and specifically focus on one of the three core ministry functions. You may submit more than one story. All submissions are subject to approval by the editorial board. See below for more information and helpful guidelines for writing your story. If you have further questions, please send an email to: [email protected] Helpful Guidelines for Writing Your Story 1. Keep your story clear and concise. State the facts but avoid revealing any personal or confidential details (names of certain individuals, security sensitive info, etc.) that would detract from your story. 2. Limit your story to 500-1000 words or less (about 2-3 double-spaced pages if using 12 point New Times Roman font).