Maxwell Relations: a Wealth of Partial Derivatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thermodynamic Potentials and Natural Variables

Revista Brasileira de Ensino de Física, vol. 42, e20190127 (2020) Articles www.scielo.br/rbef cb DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1806-9126-RBEF-2019-0127 Licença Creative Commons Thermodynamic Potentials and Natural Variables M. Amaku1,2, F. A. B. Coutinho*1, L. N. Oliveira3 1Universidade de São Paulo, Faculdade de Medicina, São Paulo, SP, Brasil 2Universidade de São Paulo, Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária e Zootecnia, São Paulo, SP, Brasil 3Universidade de São Paulo, Instituto de Física de São Carlos, São Carlos, SP, Brasil Received on May 30, 2019. Revised on September 13, 2018. Accepted on October 4, 2019. Most books on Thermodynamics explain what thermodynamic potentials are and how conveniently they describe the properties of physical systems. Certain books add that, to be useful, the thermodynamic potentials must be expressed in their “natural variables”. Here we show that, given a set of physical variables, an appropriate thermodynamic potential can always be defined, which contains all the thermodynamic information about the system. We adopt various perspectives to discuss this point, which to the best of our knowledge has not been clearly presented in the literature. Keywords: Thermodynamic Potentials, natural variables, Legendre transforms. 1. Introduction same statement cannot be applied to the temperature. In real fluids, even in simple ones, the proportionality Basic concepts are most easily understood when we dis- to T is washed out, and the Internal Energy is more cuss simple systems. Consider an ideal gas in a cylinder. conveniently expressed as a function of the entropy and The cylinder is closed, its walls are conducting, and a volume: U = U(S, V ). -

PDF Version of Helmholtz Free Energy

Free energy Free Energy at Constant T and V Starting with the First Law dU = δw + δq At constant temperature and volume we have δw = 0 and dU = δq Free Energy at Constant T and V Starting with the First Law dU = δw + δq At constant temperature and volume we have δw = 0 and dU = δq Recall that dS ≥ δq/T so we have dU ≤ TdS Free Energy at Constant T and V Starting with the First Law dU = δw + δq At constant temperature and volume we have δw = 0 and dU = δq Recall that dS ≥ δq/T so we have dU ≤ TdS which leads to dU - TdS ≤ 0 Since T and V are constant we can write this as d(U - TS) ≤ 0 The quantity in parentheses is a measure of the spontaneity of the system that depends on known state functions. Definition of Helmholtz Free Energy We define a new state function: A = U -TS such that dA ≤ 0. We call A the Helmholtz free energy. At constant T and V the Helmholtz free energy will decrease until all possible spontaneous processes have occurred. At that point the system will be in equilibrium. The condition for equilibrium is dA = 0. A time Definition of Helmholtz Free Energy Expressing the change in the Helmholtz free energy we have ∆A = ∆U – T∆S for an isothermal change from one state to another. The condition for spontaneous change is that ∆A is less than zero and the condition for equilibrium is that ∆A = 0. We write ∆A = ∆U – T∆S ≤ 0 (at constant T and V) Definition of Helmholtz Free Energy Expressing the change in the Helmholtz free energy we have ∆A = ∆U – T∆S for an isothermal change from one state to another. -

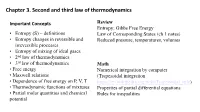

Chapter 3. Second and Third Law of Thermodynamics

Chapter 3. Second and third law of thermodynamics Important Concepts Review Entropy; Gibbs Free Energy • Entropy (S) – definitions Law of Corresponding States (ch 1 notes) • Entropy changes in reversible and Reduced pressure, temperatures, volumes irreversible processes • Entropy of mixing of ideal gases • 2nd law of thermodynamics • 3rd law of thermodynamics Math • Free energy Numerical integration by computer • Maxwell relations (Trapezoidal integration • Dependence of free energy on P, V, T https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trapezoidal_rule) • Thermodynamic functions of mixtures Properties of partial differential equations • Partial molar quantities and chemical Rules for inequalities potential Major Concept Review • Adiabats vs. isotherms p1V1 p2V2 • Sign convention for work and heat w done on c=C /R vm system, q supplied to system : + p1V1 p2V2 =Cp/CV w done by system, q removed from system : c c V1T1 V2T2 - • Joule-Thomson expansion (DH=0); • State variables depend on final & initial state; not Joule-Thomson coefficient, inversion path. temperature • Reversible change occurs in series of equilibrium V states T TT V P p • Adiabatic q = 0; Isothermal DT = 0 H CP • Equations of state for enthalpy, H and internal • Formation reaction; enthalpies of energy, U reaction, Hess’s Law; other changes D rxn H iD f Hi i T D rxn H Drxn Href DrxnCpdT Tref • Calorimetry Spontaneous and Nonspontaneous Changes First Law: when one form of energy is converted to another, the total energy in universe is conserved. • Does not give any other restriction on a process • But many processes have a natural direction Examples • gas expands into a vacuum; not the reverse • can burn paper; can't unburn paper • heat never flows spontaneously from cold to hot These changes are called nonspontaneous changes. -

Math Background for Thermodynamics ∑

MATH BACKGROUND FOR THERMODYNAMICS A. Partial Derivatives and Total Differentials Partial Derivatives Given a function f(x1,x2,...,xm) of m independent variables, the partial derivative ∂ f of f with respect to x , holding the other m-1 independent variables constant, , is defined by i ∂ xi xj≠i ∂ f fx( , x ,..., x+ ∆ x ,..., x )− fx ( , x ,..., x ,..., x ) = 12ii m 12 i m ∂ lim ∆ xi x →∆ 0 xi xj≠i i nRT Example: If p(n,V,T) = , V ∂ p RT ∂ p nRT ∂ p nR = = − = ∂ n V ∂V 2 ∂T V VT,, nTV nV , Total Differentials Given a function f(x1,x2,...,xm) of m independent variables, the total differential of f, df, is defined by m ∂ f df = ∑ dx ∂ i i=1 xi xji≠ ∂ f ∂ f ∂ f = dx + dx + ... + dx , ∂ 1 ∂ 2 ∂ m x1 x2 xm xx2131,...,mm xxx , ,..., xx ,..., m-1 where dxi is an infinitesimally small but arbitrary change in the variable xi. nRT Example: For p(n,V,T) = , V ∂ p ∂ p ∂ p dp = dn + dV + dT ∂ n ∂ V ∂ T VT,,, nT nV RT nRT nR = dn − dV + dT V V 2 V B. Some Useful Properties of Partial Derivatives 1. The order of differentiation in mixed second derivatives is immaterial; e.g., for a function f(x,y), ∂ ∂ f ∂ ∂ f ∂ 22f ∂ f = or = ∂ y ∂ xx ∂ ∂ y ∂∂yx ∂∂xy y x x y 2 in the commonly used short-hand notation. (This relation can be shown to follow from the definition of partial derivatives.) 2. Given a function f(x,y): ∂ y 1 a. = etc. ∂ f ∂ f x ∂ y x ∂ f ∂ y ∂ x b. -

( ∂U ∂T ) = ∂CV ∂V = 0, Which Shows That CV Is Independent of V . 4

so we have ∂ ∂U ∂ ∂U ∂C =0 = = V =0, ∂T ∂V ⇒ ∂V ∂T ∂V which shows that CV is independent of V . 4. Using Maxwell’s relations. Show that (∂H/∂p) = V T (∂V/∂T ) . T − p Start with dH = TdS+ Vdp. Now divide by dp, holding T constant: dH ∂H ∂S [at constant T ]= = T + V. dp ∂p ∂p T T Use the Maxwell relation (Table 9.1 of the text), ∂S ∂V = ∂p − ∂T T p to get the result ∂H ∂V = T + V. ∂p − ∂T T p 97 5. Pressure dependence of the heat capacity. (a) Show that, in general, for quasi-static processes, ∂C ∂2V p = T . ∂p − ∂T2 T p (b) Based on (a), show that (∂Cp/∂p)T = 0 for an ideal gas. (a) Begin with the definition of the heat capacity, δq dS C = = T , p dT dT for a quasi-static process. Take the derivative: ∂C ∂2S ∂2S p = T = T (1) ∂p ∂p∂T ∂T∂p T since S is a state function. Substitute the Maxwell relation ∂S ∂V = ∂p − ∂T T p into Equation (1) to get ∂C ∂2V p = T . ∂p − ∂T2 T p (b) For an ideal gas, V (T )=NkT/p,so ∂V Nk = , ∂T p p ∂2V =0, ∂T2 p and therefore, from part (a), ∂C p =0. ∂p T 98 (a) dU = TdS+ PdV + μdN + Fdx, dG = SdT + VdP+ Fdx, − ∂G F = , ∂x T,P 1 2 G(x)= (aT + b)xdx= 2 (aT + b)x . ∂S ∂F (b) = , ∂x − ∂T T,P x,P ∂S ∂F (c) = = ax, ∂x − ∂T − T,P x,P S(x)= ax dx = 1 ax2. -

3 More Applications of Derivatives

3 More applications of derivatives 3.1 Exact & inexact di®erentials in thermodynamics So far we have been discussing total or \exact" di®erentials µ ¶ µ ¶ @u @u du = dx + dy; (1) @x y @y x but we could imagine a more general situation du = M(x; y)dx + N(x; y)dy: (2) ¡ ¢ ³ ´ If the di®erential is exact, M = @u and N = @u . By the identity of mixed @x y @y x partial derivatives, we have µ ¶ µ ¶ µ ¶ @M @2u @N = = (3) @y x @x@y @x y Ex: Ideal gas pV = RT (for 1 mole), take V = V (T; p), so µ ¶ µ ¶ @V @V R RT dV = dT + dp = dT ¡ 2 dp (4) @T p @p T p p Now the work done in changing the volume of a gas is RT dW = pdV = RdT ¡ dp: (5) p Let's calculate the total change in volume and work done in changing the system between two points A and C in p; T space, along paths AC or ABC. 1. Path AC: dT T ¡ T ¢T ¢T = 2 1 ´ so dT = dp (6) dp p2 ¡ p1 ¢p ¢p T ¡ T1 ¢T ¢T & = ) T ¡ T1 = (p ¡ p1) (7) p ¡ p1 ¢p ¢p so (8) R ¢T R ¢T R ¢T dV = dp ¡ [T + (p ¡ p )]dp = ¡ (T ¡ p )dp (9) p ¢p p2 1 ¢p 1 p2 1 ¢p 1 R ¢T dW = ¡ (T ¡ p )dp (10) p 1 ¢p 1 1 T (p ,T ) 2 2 C (p,T) (p1,T1) A B p Figure 1: Path in p; T plane for thermodynamic process. -

Thermodynamics

ME346A Introduction to Statistical Mechanics { Wei Cai { Stanford University { Win 2011 Handout 6. Thermodynamics January 26, 2011 Contents 1 Laws of thermodynamics 2 1.1 The zeroth law . .3 1.2 The first law . .4 1.3 The second law . .5 1.3.1 Efficiency of Carnot engine . .5 1.3.2 Alternative statements of the second law . .7 1.4 The third law . .8 2 Mathematics of thermodynamics 9 2.1 Equation of state . .9 2.2 Gibbs-Duhem relation . 11 2.2.1 Homogeneous function . 11 2.2.2 Virial theorem / Euler theorem . 12 2.3 Maxwell relations . 13 2.4 Legendre transform . 15 2.5 Thermodynamic potentials . 16 3 Worked examples 21 3.1 Thermodynamic potentials and Maxwell's relation . 21 3.2 Properties of ideal gas . 24 3.3 Gas expansion . 28 4 Irreversible processes 32 4.1 Entropy and irreversibility . 32 4.2 Variational statement of second law . 32 1 In the 1st lecture, we will discuss the concepts of thermodynamics, namely its 4 laws. The most important concepts are the second law and the notion of Entropy. (reading assignment: Reif x 3.10, 3.11) In the 2nd lecture, We will discuss the mathematics of thermodynamics, i.e. the machinery to make quantitative predictions. We will deal with partial derivatives and Legendre transforms. (reading assignment: Reif x 4.1-4.7, 5.1-5.12) 1 Laws of thermodynamics Thermodynamics is a branch of science connected with the nature of heat and its conver- sion to mechanical, electrical and chemical energy. (The Webster pocket dictionary defines, Thermodynamics: physics of heat.) Historically, it grew out of efforts to construct more efficient heat engines | devices for ex- tracting useful work from expanding hot gases (http://www.answers.com/thermodynamics). -

7 Apr 2021 Thermodynamic Response Functions . L03–1 Review Of

7 apr 2021 thermodynamic response functions . L03{1 Review of Thermodynamics. 3: Second-Order Quantities and Relationships Maxwell Relations • Idea: Each thermodynamic potential gives rise to several identities among its second derivatives, known as Maxwell relations, which express the integrability of the fundamental identity of thermodynamics for that potential, or equivalently the fact that the potential really is a thermodynamical state function. • Example: From the fundamental identity of thermodynamics written in terms of the Helmholtz free energy, dF = −S dT − p dV + :::, the fact that dF really is the differential of a state function implies that @ @F @ @F @S @p = ; or = : @V @T @T @V @V T;N @T V;N • Other Maxwell relations: From the same identity, if F = F (T; V; N) we get two more relations. Other potentials and/or pairs of variables can be used to obtain additional relations. For example, from the Gibbs free energy and the identity dG = −S dT + V dp + µ dN, we get three relations, including @ @G @ @G @S @V = ; or = − : @p @T @T @p @p T;N @T p;N • Applications: Some measurable quantities, response functions such as heat capacities and compressibilities, are second-order thermodynamical quantities (i.e., their definitions contain derivatives up to second order of thermodynamic potentials), and the Maxwell relations provide useful equations among them. Heat Capacities • Definitions: A heat capacity is a response function expressing how much a system's temperature changes when heat is transferred to it, or equivalently how much δQ is needed to obtain a given dT . The general definition is C = δQ=dT , where for any reversible transformation δQ = T dS, but the value of this quantity depends on the details of the transformation. -

Thermodynamic Analysis Based on the Second-Order Variations of Thermodynamic Potentials

Theoret. Appl. Mech., Vol.35, No.1-3, pp. 215{234, Belgrade 2008 Thermodynamic analysis based on the second-order variations of thermodynamic potentials Vlado A. Lubarda ¤ Abstract An analysis of the Gibbs conditions of stable thermodynamic equi- librium, based on the constrained minimization of the four fundamen- tal thermodynamic potentials, is presented with a particular attention given to the previously unexplored connections between the second- order variations of thermodynamic potentials. These connections are used to establish the convexity properties of all potentials in relation to each other, which systematically deliver thermodynamic relationships between the speci¯c heats, and the isentropic and isothermal bulk mod- uli and compressibilities. The comparison with the classical derivation is then given. Keywords: Gibbs conditions, internal energy, second-order variations, speci¯c heats, thermodynamic potentials 1 Introduction The Gibbs conditions of thermodynamic equilibrium are of great importance in the analysis of the equilibrium and stability of homogeneous and heterogeneous thermodynamic systems [1]. The system is in a thermodynamic equilibrium if its state variables do not spontaneously change with time. As a consequence of the second law of thermodynamics, the equilibrium state of an isolated sys- tem at constant volume and internal energy is the state with the maximum value of the total entropy. Alternatively, among all neighboring states with the ¤Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, University of California, San Diego; La Jolla, CA 92093-0411, USA and Montenegrin Academy of Sciences and Arts, Rista Stijovi¶ca5, 81000 Podgorica, Montenegro, e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] 215 216 Vlado A. Lubarda same volume and total entropy, the equilibrium state is one with the lowest total internal energy. -

Vector Calculus and Differential Forms with Applications To

Vector Calculus and Differential Forms with Applications to Electromagnetism Sean Roberson May 7, 2015 PREFACE This paper is written as a final project for a course in vector analysis, taught at Texas A&M University - San Antonio in the spring of 2015 as an independent study course. Students in mathematics, physics, engineering, and the sciences usually go through a sequence of three calculus courses before go- ing on to differential equations, real analysis, and linear algebra. In the third course, traditionally reserved for multivariable calculus, stu- dents usually learn how to differentiate functions of several variable and integrate over general domains in space. Very rarely, as was my case, will professors have time to cover the important integral theo- rems using vector functions: Green’s Theorem, Stokes’ Theorem, etc. In some universities, such as UCSD and Cornell, honors students are able to take an accelerated calculus sequence using the text Vector Cal- culus, Linear Algebra, and Differential Forms by John Hamal Hubbard and Barbara Burke Hubbard. Here, students learn multivariable cal- culus using linear algebra and real analysis, and then they generalize familiar integral theorems using the language of differential forms. This paper was written over the course of one semester, where the majority of the book was covered. Some details, such as orientation of manifolds, topology, and the foundation of the integral were skipped to save length. The paper should still be readable by a student with at least three semesters of calculus, one course in linear algebra, and one course in real analysis - all at the undergraduate level. -

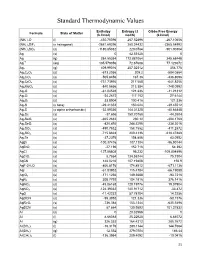

Standard Thermodynamic Values

Standard Thermodynamic Values Enthalpy Entropy (J Gibbs Free Energy Formula State of Matter (kJ/mol) mol/K) (kJ/mol) (NH4)2O (l) -430.70096 267.52496 -267.10656 (NH4)2SiF6 (s hexagonal) -2681.69296 280.24432 -2365.54992 (NH4)2SO4 (s) -1180.85032 220.0784 -901.90304 Ag (s) 0 42.55128 0 Ag (g) 284.55384 172.887064 245.68448 Ag+1 (aq) 105.579056 72.67608 77.123672 Ag2 (g) 409.99016 257.02312 358.778 Ag2C2O4 (s) -673.2056 209.2 -584.0864 Ag2CO3 (s) -505.8456 167.36 -436.8096 Ag2CrO4 (s) -731.73976 217.568 -641.8256 Ag2MoO4 (s) -840.5656 213.384 -748.0992 Ag2O (s) -31.04528 121.336 -11.21312 Ag2O2 (s) -24.2672 117.152 27.6144 Ag2O3 (s) 33.8904 100.416 121.336 Ag2S (s beta) -29.41352 150.624 -39.45512 Ag2S (s alpha orthorhombic) -32.59336 144.01328 -40.66848 Ag2Se (s) -37.656 150.70768 -44.3504 Ag2SeO3 (s) -365.2632 230.12 -304.1768 Ag2SeO4 (s) -420.492 248.5296 -334.3016 Ag2SO3 (s) -490.7832 158.1552 -411.2872 Ag2SO4 (s) -715.8824 200.4136 -618.47888 Ag2Te (s) -37.2376 154.808 43.0952 AgBr (s) -100.37416 107.1104 -96.90144 AgBrO3 (s) -27.196 152.716 54.392 AgCl (s) -127.06808 96.232 -109.804896 AgClO2 (s) 8.7864 134.55744 75.7304 AgCN (s) 146.0216 107.19408 156.9 AgF•2H2O (s) -800.8176 174.8912 -671.1136 AgI (s) -61.83952 115.4784 -66.19088 AgIO3 (s) -171.1256 149.3688 -93.7216 AgN3 (s) 308.7792 104.1816 376.1416 AgNO2 (s) -45.06168 128.19776 19.07904 AgNO3 (s) -124.39032 140.91712 -33.472 AgO (s) -11.42232 57.78104 14.2256 AgOCN (s) -95.3952 121.336 -58.1576 AgReO4 (s) -736.384 153.1344 -635.5496 AgSCN (s) 87.864 130.9592 101.37832 Al (s) -

Energy and Enthalpy Thermodynamics

Energy and Energy and Enthalpy Thermodynamics The internal energy (E) of a system consists of The energy change of a reaction the kinetic energy of all the particles (related to is measured at constant temperature) plus the potential energy of volume (in a bomb interaction between the particles and within the calorimeter). particles (eg bonding). We can only measure the change in energy of the system (units = J or Nm). More conveniently reactions are performed at constant Energy pressure which measures enthalpy change, ∆H. initial state final state ∆H ~ ∆E for most reactions we study. final state initial state ∆H < 0 exothermic reaction Energy "lost" to surroundings Energy "gained" from surroundings ∆H > 0 endothermic reaction < 0 > 0 2 o Enthalpy of formation, fH Hess’s Law o Hess's Law: The heat change in any reaction is the The standard enthalpy of formation, fH , is the change in enthalpy when one mole of a substance is formed from same whether the reaction takes place in one step or its elements under a standard pressure of 1 atm. several steps, i.e. the overall energy change of a reaction is independent of the route taken. The heat of formation of any element in its standard state is defined as zero. o The standard enthalpy of reaction, H , is the sum of the enthalpy of the products minus the sum of the enthalpy of the reactants. Start End o o o H = prod nfH - react nfH 3 4 Example Application – energy foods! Calculate Ho for CH (g) + 2O (g) CO (g) + 2H O(l) Do you get more energy from the metabolism of 1.0 g of sugar or