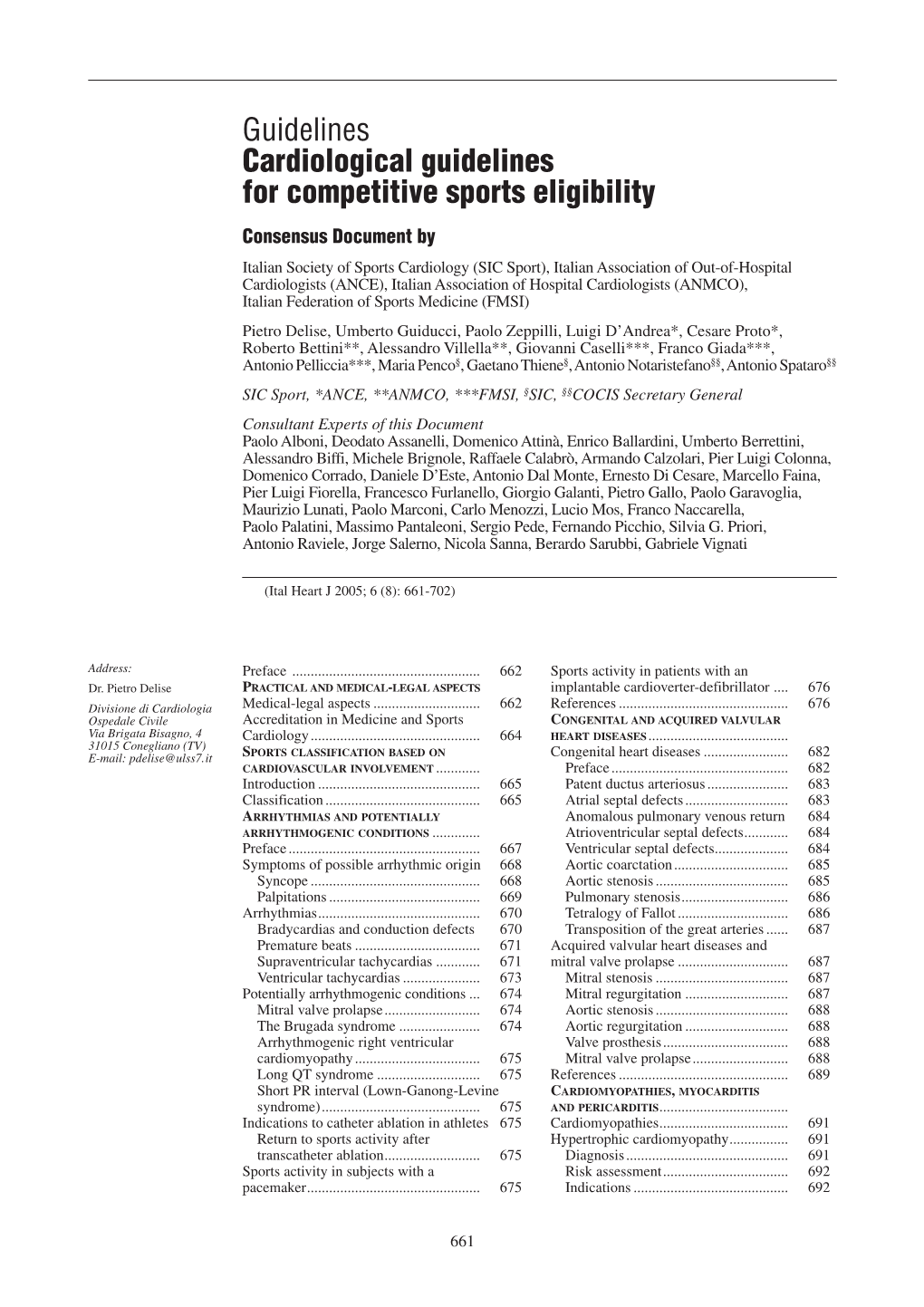

Guidelines Cardiological Guidelines for Competitive Sports Eligibility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transportation Design

04 sistema design nelle imprese di Roma e del Lazio sistema design nelle imprese DESIGN FOR MADE IN ITALY Transportation Design Ilaria Sacco Antonio Dal Monte Rondine Motor Modelleria Di Laurenzio Arca Camper Belumbury diid Diamond Style Team 04 sistema design nelle imprese di Roma e del Lazio sistema design nelle imprese DESIGN FOR MADE IN ITALY Transportation Design Direttore responsabile | Managing Director Tonino Paris Direttore | Director Carlo Martino Coordinamento scientifico | Scientific Coordination Committe Osservatorio scientifico sul Design del Dipartimanto ITACA, Industrial Design Tecnologia dell’Architettura, Cultura dell’Ambiente, Sapienza Università di Roma Redazione | Editorial Staff Luca Bradini Nicoletta Cardano Ivo Caruso Paolo Ciacci Emanuele Cucuzza Stefano Lacu Antonio Las Casas Sara Palumbo Filippo Pernisco Felice Ragazzo Silvia Segoloni Clara Tosi Pamphili Segreteria di redazione | Editorial Headquarter Via Flaminia 70-72, 00196 Roma tel/fax +39 06 49919016/15 [email protected] Traduzione | Translations Claudia Vettore Progetto grafico | Graphic design Roberta Sacco Impaginazione | Production Sara Palumbo Editore | Publisher Rdesignpress DESIGN FOR Via Angelo Brunetti 42, 00186 Roma tel/fax +39 06 3225362 MADE IN ITALY e-mail: [email protected] sistema design nelle imprese di Roma e del Lazio n°4_agosto 2009 Distribuzione librerie | Distribution through bookstores Joo distribution – Milano allegato alla rivista Distribuzione estero | Distribution for other countries S.i.e.s. srl – Milano 20092 Cinisello -

Biological Age, Chronological Age

SIMOULTANEOUS TRANSLATION XXXVI PROVIDED NATIONAL CONGRESS 90 YEARS OF THE ITALIAN FEDERATION OF of the Italian Federation of Sports Medicine SPORTS MEDICINE ( 1929 – 2019 ) BIOLOGICAL AGE, CHRONOLOGICAL AGE PRELIMINARY PROGRAMME ROME 27-29 HOTEL ROME CAVALIERI MARCH 2019 INDEX 2 PATRONAGES 3 COMMITTEES 4 SPEAKERS AND MODERATORS 7 SCIENTIFIC PROGRAMME 19 GENERAL AND SCIENTIFIC INFORMATION NATIONAL CONGRESS of the Italian Federation ROMA 27-29 XXXVIof Sports Medicine HOTEL ROME CAVALIERI MARZO 2019 FMSI applied for the High Patronage of the President of the Italian Republic Requested Patronages: Italian Council of Ministers European Parliament Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and European Commissioner for Health International Cooperation European Commissioner for Sport Italian Ministry of the Interior Fédération Internationale de Médecine du Italian Ministry of Health Sport Italian Ministry of Education, University and European Federation of Sports Medicine Research Associations Italian National Olympic Committee European Union of Medical Specialists Italian Paralympic Committee National University Council National Federation of the Order of Physicians, Surgeons and Dentists University of Rome “Foro Italico” University of Rome “Sapienza” University of Rome “Tor Vergata” PRESIDENT OF THE CONGRESS Maurizio Casasco HONORARY PRESIDENT OF THE 90° Giorgio Santilli ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Maurizio Casasco Gianfranco Beltrami Vincenzo Russo Gabriele Brandoni Vincenzo Maria Ieracitano Adolfo Marciano Attilio Parisi Claudio Pecci Antonio Pezzano -

Sicea-Progetti.Pdf

TIMEPROOF NEL TEMPO The company was founded in 1962 along Nel 1962 venne fondata l’azienda e creato il with Sicea’s trademark, a handicraft laboratory marchio Sicea, laboratorio artigianale con una that manufactured tables and furniture readily produzione di tavoli e mobili, subito apprezzata appreciated by the European market. dai mercati europei. Sicea is now an industrial reality but it started Da attività artigianale, la Sicea si é trasformata as an artisan activity; striding with tenacity in realtà industriale, percorrendo con tenacia e and determination along the steps of its determinazione tutte le tappe della sua crescita professional growth paying particular attention aziendale mantenendo alta l’attenzione nei to the evolution of market systems, design and confronti dell’evoluzione dei sistemi di mercato, technological innovation. design e innovazione tecnologica. SICEA DESIGN SICEA DESIGN Sicea has been manufacturing tables for La Sicea produce tavoli per l’arredamento da the past 40 years. Our long experience oltre quarant’anni. Una lunghissima esperienza has followed the tastes and trends of two maturata nel tempo insieme ai gusti e alle generations of consumers. tendenze di due generazioni di consumatori. For Sicea, tables and furniture represent Per Sicea, il tavolo, il mobile, rappresentano the expression of a wide range of creative un’espressione dalle mille possibilità creative sia possibilities for the designer, manufacturer per designer e produttori sia per gli utilizzatori. and consumer. Il tavolo e i complementi d’arredo si trasformano The tables and furniture accessories change seguendo le inclinazioni e i gusti di chi li sceglie: according to the preferences and taste of prolunghe a scomparsa, strutture estraibili, the customer: hidden extensions, extractible cerniere nascoste, rendono forme e linee frames, hidden hinges that adapt forms and integrabili in qualsiasi situazione abitativa. -

Biological Age, Chronological Age

SIMOULTANEOUS TRANSLATION XXXVI PROVIDED NATIONAL CONGRESS 90 YEARS OF THE ITALIAN FEDERATION OF of the Italian Federation of Sports Medicine SPORTS MEDICINE (1929 – 2019) BIOLOGICAL AGE, CHRONOLOGICAL AGE FINAL PROGRAMME ROME 27-29 HOTEL ROME CAVALIERI MARCH 2019 INDEX 2 PATRONAGES 3 COMMITTEES 4 SPEAKERS AND MODERATORS 9 SCIENTIFIC PROGRAMME 23 GENERAL AND SCIENTIFIC INFORMATION NATIONAL CONGRESS of the Italian Federation ROMA 27-29 XXXVIof Sports Medicine HOTEL ROME CAVALIERI MARZO 2019 Patronages: Italian Ministry of Health European Commission Representation in Italy Italian National Olympic Committee International Federation of Sports Medicine Italian Paralympic Committee European Federation of Sports Medicine Associations National Professional League National University Council National Federation of the Order of Physicians, Surgeons and Dentists University of Rome “Foro Italico” University of Rome “Tor Vergata” PRESIDENT OF THE CONGRESS Maurizio Casasco HONORARY PRESIDENT OF THE 90° Giorgio Santilli ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Maurizio Casasco, Gianfranco Beltrami, Vincenzo Russo, Gabriele Brandoni, Vincenzo Maria Ieracitano, Adolfo Marciano, Attilio Parisi, Claudio Pecci, Antonio Pezzano, Marco Scorcu, Maria Triassi SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE OF THE 90° ANNIVERSARY CONGRESS Fabio Pigozzi, Norbert Bachl, Alessandro Biffi, Francesco Botré, Eduardo H. De Rose, Nicola Di Daniele, Luigi Di Luigi, Ranieri Guerra, Sergio Pecorelli HISTORICAL COMMITTEE OF THE 90° ANNIVERSARY CONGRESS Alfredo Calligaris, Paolo Cerretelli, Antonio Dal Monte, Carlo Gabriele -

Università Degli Studi Di Roma "Tor Vergata"

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI ROMA "TOR VERGATA" FACOLTA' DI MEDICINA E CHIRURGIA DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN SCIENZE DELLO SPORT XXI CICLO DEL CORSO DI DOTTORATO MATCH ANALYSIS IN TEAM SPORTS DOTTORANDO: Bruno RUSCELLO A.A. 2008/2009 Tutor: Professor Attilio SACRIPANTI Coordinatore: Professor Antonio LOMBARDO A mio padre ii Acknowledgments: I wish to thank many people. This work would not have been possible without their precious help. First of all my deepest gratitude and respect to Professor Attilio Sacripanti who superbly supervised my efforts as a Ph.D. Candidate all the way through these three working years. His knowledge, experience, humanity and brilliant sense of humour were an incomparable help to me, in every circumstances. Thank You, Professor. Thanks to the Italian Hockey Federation and its President Luca Di Mauro, who supported and encouraged me in all these years. Then all my friends, my colleagues, my players: really thank you for your kindness and patience. I wish to thank Gianluca Iaccarino, the brilliant statistician who shared with me the deep love for Hockey and Match Analysis since the early 1990s. I wish to thank Andrea Ciuffarella for the precious contribution given to the study of football, reported in this thesis. Many thanks to Valentina Camomilla Ph.D., Domenico Cherubini Ph.D., and Professor Aurelio Cappozzo, of “Foro Italico” University of Rome, Department of Human Movement and Sport Sciences. I also had the privilege of visiting many Universities abroad and the honour to talk to many scholars and professors, about the topic of this thesis. Indeed many suggestions of this thesis were born during these fantastic talks.