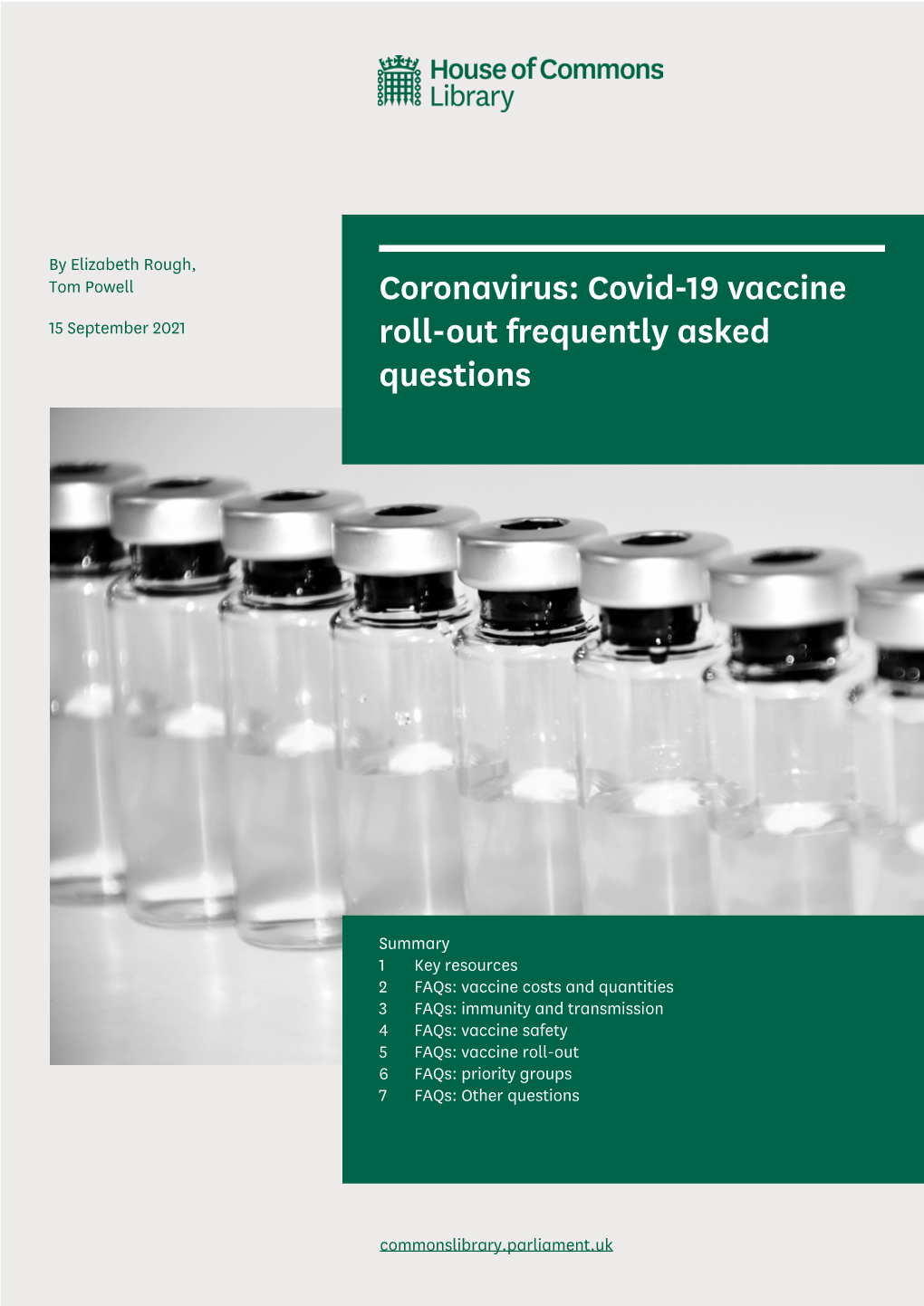

Coronavirus: Covid-19 Vaccine Roll-Out Frequently Asked Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vaccines for Preteens

| DISEASES and the VACCINES THAT PREVENT THEM | INFORMATION FOR PARENTS Vaccines for Preteens: What Parents Should Know Last updated JANUARY 2017 Why does my child need vaccines now? to get vaccinated. The best time to get the flu vaccine is as soon as it’s available in your community, ideally by October. Vaccines aren’t just for babies. Some of the vaccines that While it’s best to be vaccinated before flu begins causing babies get can wear off as kids get older. And as kids grow up illness in your community, flu vaccination can be beneficial as they may come in contact with different diseases than when long as flu viruses are circulating, even in January or later. they were babies. There are vaccines that can help protect your preteen or teen from these other illnesses. When should my child be vaccinated? What vaccines does my child need? A good time to get these vaccines is during a yearly health Tdap Vaccine checkup. Your preteen or teen can also get these vaccines at This vaccine helps protect against three serious diseases: a physical exam required for sports, school, or camp. It’s a tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis (whooping cough). good idea to ask the doctor or nurse every year if there are any Preteens should get Tdap at age 11 or 12. If your teen didn’t vaccines that your child may need. get a Tdap shot as a preteen, ask their doctor or nurse about getting the shot now. What else should I know about these vaccines? These vaccines have all been studied very carefully and are Meningococcal Vaccine safe. -

(Public Pack)Minutes Document for London Assembly (Plenary), 04/02

MINUTES Meeting: London Assembly (Plenary) Date: Thursday 4 February 2021 Time: 10.00 am Place: Virtual Meeting Copies of the minutes may be found at: http://www.london.gov.uk/mayor-assembly/london- assembly/whole-assembly Present: Navin Shah AM (Chair) Susan Hall AM Tony Arbour AM (Deputy Chairman) David Kurten AM Jennette Arnold OBE AM Joanne McCartney AM Shaun Bailey AM Dr Alison Moore AM Siân Berry AM Steve O'Connell AM Andrew Boff AM Caroline Pidgeon MBE AM Léonie Cooper AM Keith Prince AM Unmesh Desai AM Murad Qureshi AM Tony Devenish AM Caroline Russell AM Len Duvall AM Dr Onkar Sahota AM Florence Eshalomi AM MP Peter Whittle AM Nicky Gavron AM City Hall, The Queen’s Walk, London SE1 2AA Enquiries: 020 7983 4100 minicom: 020 7983 4458 www.london.gov.uk v1 2015 Greater London Authority London Assembly (Plenary) Thursday 4 February 2021 1 Apologies for Absence and Chair's Announcements (Item 1) 1.1 The Chair explained that in accordance with Government regulations, the meeting was being held on a virtual basis, with Assembly Members participating remotely. 1.2 The Clerk read the roll-call of Assembly Members who were participating in the meeting. Apologies for absence were received on behalf of Gareth Bacon AM MP and Andrew Dismore AM. 1.3 On behalf the London Assembly the Chair expressed condolences to Captain Sir Tom Moore’s family following his death, noting the hope and happiness he had brought to many during the COVID-19 pandemic. 1.4 The Chair provided an update on recent Assembly activity, including: the London Assembly’s Plenary meeting questioning the Mayor on his draft 2021/22 budget; the COVID-19 and homeworking event held to explore the impact of working from home mental and physical wellbeing; and the Fire, Resilience and Emergency Planning Committee’s meeting with the London Fire Commissioner, on the impacts of COVID-19 on the London Fire Brigade. -

To Approve Pfizer-Biontech Vaccine: UK Regulator 2 December 2020

No 'corners cut' to approve Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine: UK regulator 2 December 2020 the jab began in June after interim results from early trials by US giant Pfizer and German newcomer BioNTech became available. "If you climb a mountain, you prepare and prepare," she added. "On 10th November we were at base camp. When we got the final analysis we were ready for that last sprint that takes us to today." British Health Secretary Matt Hancock said earlier the country's state-run National Health Service will start inoculations with 800,000 doses "early next week". Credit: Pixabay/CC0 Public Domain That will be ramped up to "millions" of jabs by the end of the year. Britain's independent medicines regulator said on The mass vaccination programme will begin with Wednesday no "corners have been cut" in its elderly care home residents and frontline health recommendation to approve Pfizer-BioNTech's and social care staff. COVID-19 vaccine for general use. © 2020 AFP The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) said it had used overlapping trials and "rolling reviews" since June to reach the determination in record time. "That doesn't mean any corners have been cut—none at all," June Raine, its chief executive, said at a press conference. "The safety of the public will always come first." Wednesday's announcement saw Britain become the first Western country to approve a COVID-19 vaccine for general use, with jabs set to begin for the most vulnerable from next week. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is one of several expected to gain regulatory approval in the coming weeks as similar reviews are completed. -

Strategies for Increasing Uptake of Vaccination in Pregnancy in High

Vaccine 36 (2018) 2751–2759 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Vaccine journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/vaccine Review Strategies for increasing uptake of vaccination in pregnancy in high-income countries: A systematic review ⇑ Kate Alexandra Bisset a,b, Pauline Paterson a, a The Vaccine Confidence Project, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Keppel St, London WC1E 7HT, United Kingdom b Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, South Wharf Road, St Mary’s Hospital, London W2 1NY, United Kingdom article info abstract Article history: Introduction: Vaccination in pregnancy is an effective method to protect against disease for the pregnant Received 29 November 2017 woman, foetus and new born infant. In England, it is recommended that pregnant women are vaccinated Received in revised form 22 March 2018 against pertussis and influenza. Improvement in the uptake of both pertussis and influenza vaccination Accepted 4 April 2018 among pregnant women is needed to prevent morbidity and mortality for both the pregnant women Available online 13 April 2018 and unborn child. Aim: To identify effective strategies in increasing the uptake of vaccination in pregnancy in high-income Keywords: countries and to make recommendations for England. Pertussis vaccine Methods: A systematic review of peer reviewed literature was conducted using a keyword search strategy Influenza vaccine Pregnancy applied across six databases (Medline, Embase, PsychInfo, PubMed, CINAHL and Web of Science). Articles Vaccine hesitancy were screened against an inclusion and exclusion criteria and papers included within the review were Maternal vaccination quality assessed. Strategies Results and conclusions: Twenty-two articles were included in the review. The majority of the papers included were conducted in the USA and looked at strategies to increase influenza vaccination in preg- nancy. -

Advice on Priority Groups for COVID-19 Vaccination

Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation: advice on priority groups for COVID-19 vaccination 30 December 2020 Introduction This advice is provided to facilitate the development of policy on COVID- 19 vaccination in the UK. JCVI advises that the first priorities for the current COVID-19 vaccination programme should be the prevention of COVID-19 mortality and the protection of health and social care staff and systems. Secondary priorities could include vaccination of those at increased risk of hospitalisation and at increased risk of exposure, and to maintain resilience in essential public services. This document sets out a framework for refining future advice on a national COVID-19 vaccination strategy. This advice has been developed based on a review of UK epidemiological data on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic so far (1), data on demographic and clinical risk factors for mortality and hospitalisation from COVID-19 (2-3), data on occupational exposure(4-7), a review on inequalities associated with COVID-19 (8), Phase I, II and III data on the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine and the AstraZeneca vaccine, Phase I and II data on other developmental COVID-19 vaccines (9-20), and mathematical modelling on the potential impact of different vaccination programmes (21). Considerations Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine The Committee has reviewed published and unpublished Phase I/II/III safety and efficacy data for the Pfizer BioNTech mRNA vaccine. The vaccine appears to be safe and well-tolerated, and there were no clinically concerning safety observations. The data indicate high efficacy 1 in all age groups (16 years and over), including protection against severe disease and encouraging results in older adults. -

XXV TAG Meeting

XXV TAG Meeting Twenty-Fifth Meeting of the Technical Advisory Group (TAG) on Vaccine-preventable Diseases 9-11 July 2019 Cartagena, Colombia 1 TAG Members J. Peter Figueroa TAG Chair Professor of Public Health, Epidemiology & HIV/AIDS University of the West Indies Kingston, Jamaica Jon K. Andrus Adjunct Professor and Senior Investigator Center for Global Health, Division of Vaccines and Immunization University of Colorado Washington, DC, United States Pablo Bonvehi Scientific Director VACUNAR S.A. Buenos Aires, Argentina Roger Glass* Director Fogarty International Center & Associate Director for International Research NIH/JEFIC-National Institutes of Health Bethesda, MD, United States Akira Homma Chairman of Policy and Strategy Council Bio-Manguinhos Institute Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Arlene King Adjunct Professor Dalla Lana School of Public Health University of Toronto Ontario, Canada Nancy Messonnier* Director National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Decatur, GA, United States José Ignacio Santos Secretary General Health Council Government of Mexico Mexico City, Mexico Cristiana M. Toscano 2 Head of the Department of Collective Health Institute of Tropical Pathology and Public Health, Federal University of Goiás Goiania, Brazil Cuauhtémoc Ruiz-Matus Ad hoc Secretary Unit Chief Comprehensive Family Immunization PAHO/WHO Washington, DC, United States * Not present at the meeting 3 Table of Contents Contents Acronyms ..........................................................................................................................................6 -

Protecting Young Children from Pertussis and Influenza

San Francisco Department of Public Health Barbara A Garcia, MPA Edwin M Lee Director of Health Mayor Tomás J. Aragón, MD, DrPH Health Officer January 2014 Dear Perinatal and Pediatrics Providers in San Francisco: Re: Protecting Young Infants from Pertussis and Influenza Both the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) concur with the CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommendations for protecting young infants from pertussis and influenza. ACIP Recommendations to Prevent Pertussis ACIP Recommendations to Prevent Influenza Pregnant women should receive Tdap with every Women who are or will be pregnant during flu pregnancy, ideally between 27- 36 weeks gestation. season should receive Inactivated Influenza Vaccine (IIV). Postpartum women who do not receive a Tdap vaccine Postpartum women can receive either Live during pregnancy, and who have not previously received Attenuated Influenza Vaccine (LAIV) or IIV. Tdap, should get Tdap immediately postpartum. Household and Other Contacts: Adults and adolescents Household contacts: ACIP emphasizes influenza age > 11 years, who have not previously received Tdap, vaccinations for household contacts (including should get Tdap ideally >2 weeks before close contact with children) and caregivers of children aged ≤59 a newborn. This includes partners, fathers, siblings, months, with particular emphasis on vaccinating grandparents, caregivers, and healthcare professionals. contacts of children aged <6 months. General: Everyone -

State of Nevada's COVID-19 Vaccination Program Playbook

COVID-19 Vaccination Program Nevada’s Playbook for Statewide Operations V3 NEVADA STATE IMMUNIZATION PROGRAM; DIVISION OF PUBLIC & BEHAVIORAL HEALTH; DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Acronyms ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Section 1: Public Health Preparedness Planning .......................................................................................... 6 Improvement Planning ............................................................................................................................. 6 COVID-19 Vaccination Program Planning ................................................................................................. 6 Section 2: COVID-19 Organizational Structure and Partner Involvement .................................................... 9 Nevada Planning and Coordination Team (Internal) ................................................................................ 9 Roles and Responsibilities ................................................................................................................... 10 State-Local Coordination .................................................................................................................... 10 Tribal Communities ................................................................................................................................ -

Pertussis (Whooping Cough) by Getting the Tdap Vaccine

Protect your Baby from the Start GET THE WHOOPING COUGH VACCINE IN YOUR 3RD TRIMESTER Tdap During Pregnancy PROVIDER RESOURCE TOOL KIT CONTENTS Letters of Support • CDC Dear Colleague Letter • ACOG Dear Colleague Letter Provider Backgrounders • MMWR: Updated Recommendations for Use of Tetanus Toxoid, Reduced Diphtheria Toxoid, and Acellular Pertussis Vaccine (Tdap) in Pregnant Women — Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2012 • ACOG Committee Opinion, September 2017: Update on Immunization and Pregnancy: Tetanus, Diphtheria, and Pertussis Vaccination • ACOG Committee Opinion, April 2016: Integrating Immunizations into Practice • Standing Orders for Tdap Vaccination to Pregnant Women • Immunization Action Coalition: Pertussis Questions and Answers • CDC: Tdap Vaccine Information Statement (VIS) • CDC: Provide the best prenatal care to prevent pertussis • ACOG: Physician Script Concerning Tdap Vaccination • CDC: Making a Strong Vaccine Referral to Pregnant Women Patient Handouts • Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine: Tdap Vaccination During Pregnancy • Minnesota Department of Public Health: Tdap Vaccine for Pregnant Women • Immunization Action Coalition: Cocooning Protects Babies • CDC: You Can Start Protecting your Baby from Whooping Cough Before Birth • ACOG: Frequently Asked Questions for Pregnant Women Concerning Tdap Vaccination • CDC: Poster Print Ad: Pregnant Woman • CDC: Poster Print Ad: Nursery • Survivor Story: The Van Tornhout Family • Get Them In On Time: Birth to 16 Years Immunization Schedule www.vaccinateindiana.org -

Licensed and Recommended Inactivated Oral Choleravaccines: from Development to Innovative Deployment

Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease Review Licensed and Recommended Inactivated Oral CholeraVaccines: From Development to Innovative Deployment Jacqueline Deen 1 and John D. Clemens 2,3,* 1 Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, University of the Philippines, Pedro Gil Street, Ermita, Manila 1000, Philippines; [email protected] 2 International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, GPO Box 128, Dhaka 1000, Bangladesh 3 UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, 650 Charles E Young Drive South, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1772, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +63-2-254-5205 Abstract: Cholera is a disease of poverty and occurs where there is a lack of access to clean water and adequate sanitation. Since improved water supply and sanitation infrastructure cannot be implemented immediately in many high-risk areas, vaccination against cholera is an important addi- tional tool for prevention and control. We describe the development of licensed and recommended inactivated oral cholera vaccines (OCVs), including the results of safety, efficacy and effectiveness studies and the creation of the global OCV stockpile. Over the years, the public health strategy for oral cholera vaccination has broadened—from purely pre-emptive use to reactive deployment to help control outbreaks. Limited supplies of OCV doses continues to be an important problem. We discuss various innovative dosing and delivery approaches that have been assessed and implemented and evidence of herd protection conferred by OCVs. We expect that the demand for OCVs will continue to increase in the coming years across many countries. Keywords: cholera; oral cholera vaccine; efficacy; effectiveness Citation: Deen, J.; Clemens, J.D. -

Paving the Way for Immunization

Paving the Way for Immunization XX Meeting of the Technical Advisory Group on Vaccine- preventable Diseases (TAG) 17-19 October 2012 Final Report 1 TECHNICAL ADVISORY GROUP ON VACCINE‐PREVENTABLE DISEASES XX MEETING: “PAVING THE WAY FOR IMMUNIZATION” Washington DC, 17‐19 October 2012 Members 2012 Dr. Ciro A. de Quadros Executive Vice President President Sabin Vaccine Institute Washington, D.C., United States Dr. Akira Homma Chairman Policy and Strategy Council, Bio ‐Manguinhos Institute Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Dr. Anne Schuchat Director National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Atlanta, GA, United States Dr. Arlene King Chief Medical Officer Ministry of Health and Long‐term Care Ontario, Canada Dr. Jeanette Vega Managing Director Foundation Initiatives The Rockefeller Foundation New York, NY, United States Dr. José Ignacio Santos Preciado Professor Department of Experimental Medicine Head of Clinical Research Research Division School of Medicine, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) Mexico City, Mexico _________________________________________________________________________________ 2 XX TAG Meeting, Washington DC, 2012 – Final Report Dr. Peter Figueroa (unable to attend) Chief Medical Officer Ministry of Health Kingston, Jamaica Dr. Ramiro Guerrero‐Carvajal (virtual participation) Director Research Center for Social Protection and Health Economy (PROESA) Cali, Colombia Roger Glass Director Fogarty International Center, NIH/JEFIC‐National Institutes of Health -

Anna Frances Request-746058-E0cf701a

Anna Frances MHRA [email protected] 10 South Colonnade Canary Wharf London E14 4PU United Kingdom www.gov.uk/mhra 7th May 2021 Dear Ms Frances, FOI 21/409 Thank you for your emails to MHRA customer services on 12th April 2021, where you asked questions relating to the COVID-19 vaccines, particularly inquiring on data on thromboembolic events and low platelets. In addition, you requested evidence of informed consent before people receive COVID-19 vaccines. Information on thromboembolic events and low platelets following a COVID-19 vaccine The MHRA has been proactively monitoring the safety of all approved COVID-19 vaccines for near real-time safety monitoring at the population level. A summary of Yellow Card reporting concerning the COVID-19 vaccines is published each week and can be found here. In this publication, you will find the specific information you have requested surrounding these case reports, including a breakdown of the age and sex of these patients and how many reports were fatal. The estimated number of first doses of COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca administered in the UK by 28th April was 22.6 million and 5.9 million estimated second doses, giving an overall case incidence of 10.5 per million doses. Taking into account the different numbers of patients vaccinated with COVID-19 Vaccine AstraZeneca in different age groups, there is a higher reported incidence rate in the younger adult age groups compared to the older groups. MHRA advises that this evolving evidence should be taken into account when considering the use of the vaccine.