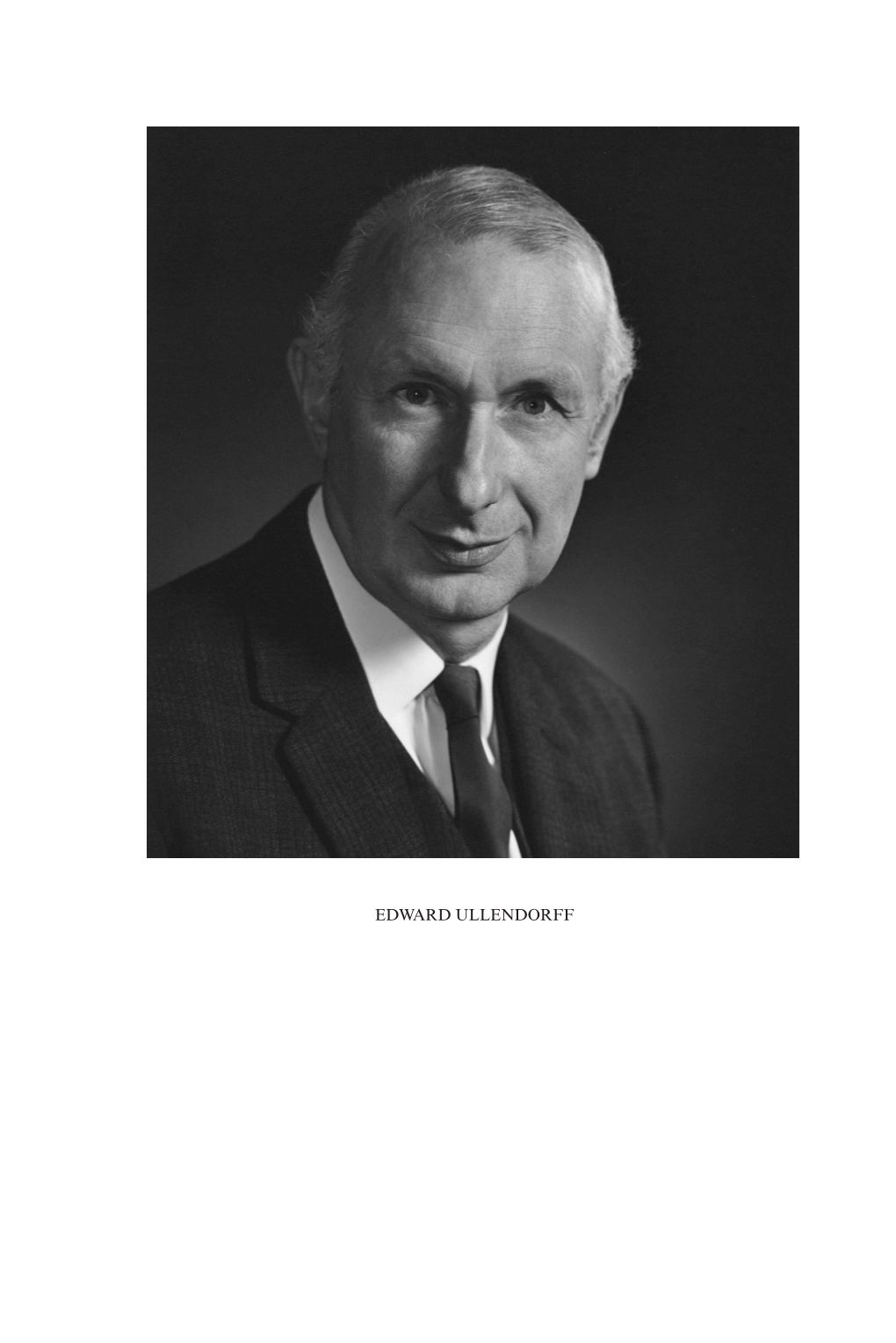

EDWARD ULLENDORFF Edward Ullendorff 1920–2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Copyright © 2014 Richard Charles Mcdonald All Rights Reserved. The

Copyright © 2014 Richard Charles McDonald All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without, limitation, preservation or instruction. GRAMMATICAL ANALYSIS OF VARIOUS BIBLICAL HEBREW TEXTS ACCORDING TO A TRADITIONAL SEMITIC GRAMMAR __________________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________________ by Richard Charles McDonald December 2014 APPROVAL SHEET GRAMMATICAL ANALYSIS OF VARIOUS BIBLICAL HEBREW TEXTS ACCORDING TO A TRADITIONAL SEMITIC GRAMMAR Richard Charles McDonald Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ Russell T. Fuller (Chair) __________________________________________ Terry J. Betts __________________________________________ John B. Polhill Date______________________________ I dedicate this dissertation to my wife, Nancy. Without her support, encouragement, and love I could not have completed this arduous task. I also dedicate this dissertation to my parents, Charles and Shelly McDonald, who instilled in me the love of the Lord and the love of His Word. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS.............................................................................................vi LIST OF TABLES.............................................................................................................vii -

Forging Plowshares in Eritrea Written by Louis Werner Photographed by Lorraine Chittock

Forging Plowshares in Eritrea Written by Louis Werner Photographed by Lorraine Chittock North of the horn of Africa, between the regions known in Pharaonic times as Kush and punt-now northeastern Sudan and Somalia, respectively-one of the ancient world's oldest trading lands has become one of the modern world's youngest sovereign states. A funnel-shaped country as large as Pennsylvania, slightly smaller than England, Eritrea's narrow "spout" runs northwest to southeast between the Red Sea and Ethiopia. At its southern end, it borders diminutive Djibouti. In the north, the mouth of the funnel opens toward Sudan. Geography and history have given Eritrea its name, which comes from the Greek word erythros, "reddish," and the Greek name for the Red Sea, Erythra Thalassa. At the throat of the Eritrean funnel, a high central plateau, the site of Asmara, the capital, separates a sweltering coastal strip from game-rich lowlands in the northwest. In the south, the Danakil Depression lies 116 meters (380') below sea-level; the highlands of the north reach up to 2700 meters (8000'). This topographically and climatically diverse land was given its form by the same violent plate tectonics that began opening the Red Sea and ripping apart Africa's Rift Valley some 25 million years ago. Eritrea's physical diversity has its analogue in the nation's citizenry. When Italian ethnographer Conti Rossini called neighboring Ethiopia "a museum of peoples," he might well have included Eritrea in his assessment. The country's 3.8 million citizens are evenly divided between Muslims and Christians, and include nine major ethnic groups speaking nine different tongues classified in language groups from Nilo-Saharan to Kushitic and Semitic. -

Handling of Out-Of-Vocabulary Words in Japanese-English Machine

International Journal of Asian Language Processing 27(2): 95-110 95 Morphological Segmentation for English-to-Tigrinya Statistical Machine Translation Yemane Tedla and Kazuhide Yamamoto Natural Language Processing Lab Nagaoka University of Technology Nagaoka city, Niigata 940-2188, Japan [email protected], [email protected] Abstract We investigate the effect of morphological segmentation schemes on the performance of English-to-Tigrinya statistical machine translation. Tigrinya is a highly inflected Semitic language spoken in Eritrea and Ethiopia. Translation involving morphologically complex and low-resource languages is challenged by a number of factors including data sparseness, word alignment and language model. We try addressing these problems through morphological segmentation of Tigrinya words. As a result of segmentation, out-of-vocabulary and perplexity of the language models were greatly reduced. We analyzed phrase-based translation with unsegmented, stemmed, and morphologically segmented corpus to examine their impact on translation quality. Our results from a relatively small parallel corpus show improvement of 1.4 BLEU or 2.4 METEOR points between the raw text model and the morphologically segmented models suggesting that segmentation affects performance of English-to-Tigrinya machine translation significantly. Keywords Tigrinya language; statistical machine translation; low-resource; morphological segmentation 1. Introduction Machine translation systems translate one natural language, the source language, to another, the target language, automatically. The accuracy of statistical machine translation (SMT) systems may not be consistently perfect but often produces a sufficient comprehension of 96 Yemane Tedla and Yamamoto Kazuhide the information in the source language. The research presented here investigates English-to-Tigrinya translation system, using the Christian Holy Bible (“the Bible” hereafter) as a parallel corpus. -

Aethiopica 16 (2013) International Journal of Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies

Aethiopica 16 (2013) International Journal of Ethiopian and Eritrean Studies ________________________________________________________________ GETATCHEW HAILE, The Hill Museum & Manuscript Library, St. John߈s University, Collegeville, MN Personalia In memoriam Taddesse Tamrat (1935߃2013) Aethiopica 16 (2013), 212߃219 ISSN: 2194߃4024 ________________________________________________________________ Edited in the Asien-Afrika-Institut Hiob Ludolf Zentrum fÛr £thiopistik der UniversitÃt Hamburg Abteilung fÛr Afrikanistik und £thiopistik by Alessandro Bausi in cooperation with Bairu Tafla, Ulrich BraukÃmper, Ludwig Gerhardt, Hilke Meyer-Bahlburg and Siegbert Uhlig Alessandro Bausi 2011 ߄ ߋFrustula nagraniticaߌ, Aethiopica 14, pp. 7߃32. ߄ ߋScoperta e riscoperta dell߈Apocalisse di Pietro fra greco, arabo ed etiopicoߌ, in: GUIDO BASTIANINI ߃ ANGELO CASANOVA (a c.), I papiri letterari cristiani: Atti del convegno internazionale di studi in memoria di Mario Naldini. Firenze, 10߃11 giugno 2010 = Stu- di e Testi di Papirologia n.s. 13, Firenze: Istituto Papirologico ߋG. Vitelliߌ, pp. 147߃160. ߄ ߋEarly Semites in Ethiopia?ߌ, RSE n.s. 3, 2011 [2012], pp. 75߃96. 2012 ߄ ߋAncient Semitic Gods on the Eritrean Shoresߌ, AION (Annali dell߈Universit¿ di Napoli ߋL߈Orientaleߌ = GIANFRANCESCO LUSINI [ed.], Current Trends in Eritrean Studies) 70, 2010 [2012], pp. 5߃15. ߄ ߋLord of Heavenߌ, RSE n.s. 4, 2012 [2013], pp. 103߃117. ߄ Review of ANTONELLA BRITA, I racconti tradizionali sulla seconda cristianizzazio- ne dell߈Etiopia = Studi Africanistici Serie Etiopica 7, Napoli: Universit¿ degli Studi di Napoli ߋL߈Orientaleߌ, Dipartimento di Studi e Ricerche su Africa e Paesi Arabi, 2010, in: Sanctorum: Rivista dell߈Associazione per lo studio della santit¿, dei culti e dell߈agiografia 8߃9, 2011߃2012, pp. 372߃374. in print ߄ ߋYasayߌ, in: EAE V, p. 31b. ߄ ߋYƼtbarÃkߌ, ibid., pp. 65b߃66b. .߄ ߋYoannƼs MƼĺraqawiߌ, ibid., pp. -

A Mobile Based Tigrigna Language Learning Tool

PAPER A MOBILE BASED TIGRIGNA LANGUAGE LEARNING TOOL A Mobile Based Tigrigna Language Learning Tool http://dx.doi.org/10.3991/ijim.v9i2.4322 Hailay Kidu University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia Abstract—Mobile learning (ML) refers to the use of mobile Currently many people visit Tigray - or hope to do so and handheld IT devices such as Personal Digital Assistants one day - because of the remarkable manner in which (PDAs), mobile telephones, laptops and tablet PC technolo- ancient historical traditions have been preserved. There- gies, in teaching and learning. Mobile learning is a new form fore anybody who wishes to visit or stay in Tigray and in of learning, using mobile network and tools, expanding Eritrea can learn the language for communication in for- digital learning channel, gaining educational information, mal class from schools, colleges or Universities. But there educational resources and educational services anytime, is no why that provides learning out of the formal class anywhere .Mobile phone is superior to a computer in porta- [2][3]. bility. This technology also facilitates the learning by your- Tigrigna is the third most spoken language in Ethiopia, self process. Learning without teacher is easy in this scenar- after Amharic and Oromo, and by far the most spoken in io. The technology encourages learn anytime and anywhere. Eritrea. It is also spoken by large immigrant communities Learning a language is different from any other subject as it around the world, in countries including Sudan, Saudi combines explicit learning of vocabulary and language rules Arabia, Germany, Italy, Sweden, the United Kingdom, with unconscious skills development in the fluent applica- tion of both these things. -

Bibliographic Guide to Further Reading

BIBLIOGRAPHIC GUIDE TO FURTHER READING The historical, memoir, travel, and technical literature on Ethiopia is immense and continually growing. A complete bibliography would require a very thick volume. Included below are most of the major books cited in the text. Journal articles, pamphlets and monographs are not included. Many worthwhile books from my own collection not specifically referenced in the footnotes have been added. Books in languages other than English, German, French, Italian and Portu guese are not listed. Among the most valuable sources for research on Ethiopia are the proceedings of the triennial International Ethiopian Studies Conferences (IESC), the most recent of which were held in East Lansing, Michigan in September 1994 and in Kyoto,Japan in Decem ber 1997. The former produced 2,372 pages of papers published as New Trends in Ethiopian Studies (2 vols. Red Sea Press, No. 1994). The latter resulted in 2,345 pp. of papers published as Ethiopia in Broader Perspective (Shokado, Kyoto, 1997, 3vols). The 14th IESC is scheduled to take place in Addis Ababa in November 2000. Many other volumes of conference proceedings have been published in Ethiopia and elsewhere during the past three decades. With only a few except ions, these have not been listed below. HISTORY AND CULTURE, GENERAL Berhanou Abebe, Historie de lithiopie d'Axoum ala revolution, Maison neuve et Larose, Paris, 1998. E. A. Wallis Budge, History ofEthiopia: Nubia and Abyssinia, Methuen, London, 192R David Buxton, The Abyssinians, Thames & Hudson, London, 1970. Franz Amadeus Dombrowski, Ethiopia sAccess to the Sea, EJ. Brill, Leiden, 1985. Jean Doresse, Ethiopia, Elee, London, 1959. -

Download the PDF File

The presence of Orthodox Ethiopians Across the Archives: in Jerusalem is attested at least from the twelfth century. At the beginning of the New Sources on the nineteenth century, Ethiopian monks Ethiopian Christian were mainly present in Dayr al-Sultan monastery, which they shared with Coptic Community in monks, with a few other Ethiopians Jerusalem, 1840–1940 accommodated in Armenian or Greek communities. However, in the middle Stéphane Ancel and of that century, Ethiopian monks came Vincent Lemire into conflict with the Coptic community concerning the occupation and the management of Dayr al-Sultan monastery. Troubles arose between Ethiopian and Coptic monks and gradually the coexistence of the two communities in the same place came to be seen as impossible, with Ethiopians and Copts each claiming full ownership of the monastery. Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century, monks and authorities from the two communities fought each other. Concerning as it did the last institution in Jerusalem to host Ethiopian monks, this conflict could have jeopardized the Ethiopian presence in the city. But during the same period, the Ethiopian Orthodox community in Jerusalem saw a great revival: the number of Ethiopians increased in the city and a number of buildings (churches and houses) dedicated to them were bought or erected. In 1876, Ethiopians received as waqf a house located in the Old City (on the same street as the Ethiopian monastery) and in 1896, a new church and monastery were completed outside the walls of the Old City (on Ethiopian Monastery Street, presently in West Jerusalem). -

A Tigrinya Language Council

NOTES AND NEWS 63 The main principle is that an Ngombe word is recognized as belonging to one or other word-group (' part of speech '), not, as in English, by its use and meaning, but by its form. As everybody knows, a Bantu word generally consists of a core or radical, to which are attached various prefixes, infixes, and suffixes. Except in ideophones, this radical in Ngombe has a tone, integral and fixed, high or low. Its basic form is Consonant-Vowel-Consonant, e.g. -OIP- (' shut'). The affixes modify the intrinsic meaning carried by the core and bind the structure of the sentence. There are four major groups of words. The nominals, containing each a fixed prefix, are invariable. The distinction between ' singular ' and 'plural' has no grammatical significance: for example, molangi (' bottle ') and milangi (' bottles ') are two independent words existing each in its own right. There are independent and dependent nominals, the latter containing a variable prefix which imitates the initial syllable of the in- dependent nominals with which they are linked. Older grammarians would call these ' adjectives ', ' pronouns ', ' adverbs ', 'conjunctions '. The next group, the verbals, differ from nominals in that alternating affixes occur both before and after the central core, the prefixes referring to the preceding independent nominal. The remaining words in Ngombe are either particles, which are used to associate words in sentence-construction, or ideophones. The independent nominals are grouped in genders—' classes ', we used to call them. Mr. Price proceeds to divide dependent nominals into adnominals and pronominals, corresponding roughly to ' adjectives ' and ' pronouns '. -

Some Observations on Composite and Multiple-Text Manuscripts in the Islamic Tradition of the Horn of Africa

Some Observations on Composite and Multiple-Text Manuscripts in the Islamic Tradition of the Horn of Africa Gori, Alessandro Published in: One-Volume Libraries: Composite and Multiple-Text Manuscripts Publication date: 2016 Document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (APA): Gori, A. (2016). Some Observations on Composite and Multiple-Text Manuscripts in the Islamic Tradition of the Horn of Africa. In M. Friedrich, & C. Schwarke (Eds.), One-Volume Libraries: Composite and Multiple-Text Manuscripts (Vol. 9, pp. 155-169). De Gruyter. Download date: 02. okt.. 2021 One-Volume Libraries: Composite and Multiple-Text Manuscripts Unauthenticated Download Date | 11/11/16 1:35 PM Studies in Manuscript Cultures Edited by Michael Friedrich Harunaga Isaacson Jörg B. Quenzer Volume 9 Unauthenticated Download Date | 11/11/16 1:35 PM One-Volume Libraries: Composite and Multiple-Text Manuscripts Edited by Michael Friedrich and Cosima Schwarke Unauthenticated Download Date | 11/11/16 1:35 PM ISBN 978-3-11-049693-2 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-049695-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-049559-1 ISSN 2365-9696 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. -

The Sultanates of Medieval Ethiopia Amélie Chekroun, Bertrand Hirsch

The Sultanates of Medieval Ethiopia Amélie Chekroun, Bertrand Hirsch To cite this version: Amélie Chekroun, Bertrand Hirsch. The Sultanates of Medieval Ethiopia. Samantha Kelly. A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, Brill, pp.86-112, 2020, 978-90-04-41943-8. 10.1163/9789004419582_005. halshs-02505420 HAL Id: halshs-02505420 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02505420 Submitted on 9 Apr 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A. Chekroun & B. Hirsch, “The Sultanates of Medieval Ethiopia” in S. Kelly (éd.), Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea, Boston, Brill, 2020, p. 86-112. PREPRINT 4 The Sultanates of Medieval Ethiopia Amélie Chekroun and Bertrand Hirsch Given its geographical situation across the Red Sea from the Arabian Peninsula and the Gulf of Aden, it is perhaps not surprising that the Horn of Africa was exposed to an early and continuous presence of Islam during the Middle Ages. Indeed, it has long been known that Muslim communities and Islamic sultanates flourished in Ethiopia and bordering lands during the medieval centuries. However, despite a sizeable amount of Ethiopian Christian documents (in Gǝʿǝz) relating to their Muslim neighbors and valuable Arabic literary sources produced outside Ethiopia and, in some cases, emanating from Ethiopian communities themselves, the Islamic presence in Ethiopia remains difficult to apprehend. -

Identity in Ethiopia: the Oromo from the 16Th to the 19Th Century

IDENTITY IN ETHIOPIA: THE OROMO FROM THE 16 TH TO THE 19 TH CENTURY By Cherri Reni Wemlinger A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Washington State University Department of History August 2008 To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the thesis of Cherri Reni Wemlinger find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ___________________________________ Chair ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ii ACKNOWLEDGMENT It is a pleasure to thank the many people who made this thesis possible. I would like to acknowledge the patience and perseverance of Heather Streets and her commitment to excellence. As my thesis chair she provided guidance and encouragement, while giving critical advice. My gratitude for her assistance goes beyond words. Thanks are also due to Candice Goucher, who provided expertise in her knowledge of Africa and kind encouragement. She was able to guide my thoughts in new directions and to make herself available during the crunch time. I would like to thank David Pietz who also served on my committee and who gave of his time to provide critical input. There are several additional people without whose assistance this work would have been greatly lacking. Thanks are due to Robert Staab, for his encouragement, guidance during the entire process, and his willingness to read the final product. Thank you to Lydia Gerber, who took hours of her time to give me ideas for sources and fresh ways to look at my subject. Her input was invaluable to me. -

Aspects of Tigrinya Literature

ASPECTS OF TIGRINYA LITERATURE (UNTIL 1974) BY HAILTJ HABTU Thesis submitted for the degree of M*Phil® at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London* June* 1981* ProQuest Number: 10673017 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673017 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 ABSTRACT This dissertation aims to study the origin and deve lopment of Tigrinya as a written language-a topic that has so far received little scholarly attention. As time and the easy accessibility of all the relevant material are limiting factors,this investigation is necessarily selective. Chapter One takes stock of all available writing in the Tigrinya language frcm its beginning in the middle of the last century up to 1974. Chapter Two briefly investigates the development of writ ten Tigrinya to serve varying functions and ends and the general direction that its development took. Chapter Three provides a glimpse of the breadth and variety of literature incorporated in the Eritrean Weekly News published in Asmara by the British Information Services frcm 1942 to 1952.