Absolute POW ER

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winebox Guide

About The Author Ian Wishart is an award-winning investigative journalist, with extensive experience in newspaper, magazine, radio and television journalism since 1982. He is also the author of the No. 1 bestseller, The Paradise Conspiracy, and Ian Wishart’s Vintage Winebox Guide. Lawyers, Guns & Money is his third book. For Matthew & Melissa Lawyers, Guns & Money A true story of horses & fairies, bankers & thieves… by Ian Wishart Howling At The Moon Publishing Ltd This book is dedicated to the broken hearts, broken promises, broken homes and broken dreams of all of those affected by both the Winebox Inquiry and the film and bloodstock investigations. This edition published 2011 (September) by Howling At The Moon Publishing Ltd PO Box 188, Kaukapakapa Auckland, New Zealand Copyright © Ian Wishart, 2011 The moral rights of the author have been asserted. Lawyers, Guns & Money is copyright. Except for the purpose of fair reviewing, no part of this publication may be copied, reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, including via technology either already in existence or developed subsequent to publication, without the express written permission of the publisher and author. All rights reserved. Print Edition ISBN 978-0-958-35684-8 Typeset in Adobe Garamon Pro, Chaparral Pro and Frutiger Edited by Steve Bloxham Book design and layout by Bozidar Jokanovic Contents prologue��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������7 -

Leighton Smith

LLEIGHTONEIGHTON SSMITHMITH: WWhathat mmakesakes hhimim ttick?ick? – IInterviewnterview IInsidenside SSUEUE BBRADFORDRADFORD: WWhyhy iiss sshehe ssmackingmacking pparents!arents! OR F F R S E SSOCIALISTOCIALIST SSWEDENWEDEN: WWhyhy ddoesoes iitt wwork?ork? E W D O O L GGODOD: Dawkins explodes the delusion! M B 7474 JJOHNOHN KKEYEY: Anything there? NZ $8.50 March - April 2007 After the release of the report on global warming prepared by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the call for a new environmental body to slow global warming and protect the planet -- a body that potentially could have policing powers to punish violators -- was led by French President Jacques Chirac. The meaning of this “effort” is that Chirac is attempting to make an international crime out of attempts to increase production and raise living standards. I am not surprised by this attempt to criminalize productive activity. In fact, I predicted it. - George Reisman, p.16 The NNooseoEEnvironmentalnvoirosnmeen tal iiss TTighteningightening NOT EXTRA: “Global Warming: The panic is offi cially over” - Monckton TAXPAYER FUNDED Subscribe NOW To The Free Radical Dear Reader, Said former editor Lindsay Perigo: Said Samuel Adams, “It does not An army of principle will penetrate The Free Radical is fearless, “How do we get government as require a majority to prevail, but where an army of soldiers cannot; it will succeed where diplomatic freedom-loving and brim-full of it might be & ought to be? It will rather an irate, tireless minority management would fail; it is great writing and good reading take a revolution inside people’s keen to set brush fi res in people’s neither the Rhine, the Channel, nor the ocean that can arrest – writing that challenges all the heads.” The Free Radical is fully minds.” The Free Radical is where its progress; it will march on the sacred cows, and gets you committed to that revolution that irate, tireless minority speaks horizon of the world .. -

Unreasonable Force New Zealand’S Journey Towards Banning the Physical Punishment of Children

Unreasonable Force New Zealand’s journey towards banning the physical punishment of children Beth Wood, Ian Hassall and George Hook with Robert Ludbrook Unreasonable Force Unreasonable Force New Zealand’s journey towards banning the physical punishment of children Beth Wood, Ian Hassall and George Hook with Robert Ludbrook © Beth Wood, Ian Hassall and George Hook, 2008. Save the Children fights for children’s rights. We deliver immediate and lasting improvements to children’s lives worldwide. Save the Children works for: • a world which respects and values each child • a world which listens to children and learns • a world where all children have hope and opportunity. ISBN: 978-0-473-13095-4 Authors: Beth Wood, Ian Hassall and George Hook with Robert Ludbrook Editor: George Hook Proof-reader: Eva Chan Publisher: Save the Children New Zealand First published: February 2008 Printer: Astra Print, Wellington To order copies of this publication, please write to: Save the Children New Zealand PO Box 6584 Marion Square Wellington 6141 New Zealand Telephone +64 4 385 6847 Fax +64 4 385 6793 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www. savethechildren.org.nz DEDICATION Our tamariki mokopuna (children) carry the divine imprint of our tupuna (ancestors), drawing from the sacred wellspring of life. As iwi (indigenous nations) we share responsibility for the well-being of our whānau (families) and tamariki mokopuna. Hitting and physical force within whānau is a viola- tion of the mana (prestige, power) and tāpu (sacredness) of those who are hit and those who hit. We will continue to work to dispel the illusion that violence is normal, acceptable or culturally valid. -

Short Circuits

SHORT CIRCUITS TIPS FOR DRIVING IN AUCKLAND 1. Never take a green light at face value. Always 8. Remember: at any given moment, 85.3% of look right and left before proceeding. Auckland drivers dont know where there is 2. Turn signals will give away your next move. A 9. Always anticipate oncoming traffic while real Auckland driver never uses them. driving down a one way street 3. There is a commonly-held belief in Auckland 10. The faster you drive through a red light, the that high-speed tailgating in heavy traffic smaller the chance you have of getting hit reduces fuel consumption as you get sucked along in the slipstream of the car in front 11. Real Auckland male drivers can remove pantyhose and a bra at 75kph in bumper to 4. Real Auckland female drivers like to apply bumper traffic - expert Auckland male drivers makeup while driving at high speed so as to can sometimes perform the same feat on their look their best for the traffic cameras female passengers as well 5. Real Auckland male drivers watch Police: 12. Seeking eye contact with another driver Stop! for driving tips automatically revokes your right of way 6. Under no circumstances should you leave a 13. Crossing two or more lanes in a single lane safe distance between you and the car in front change is considered going with the flow of you, or somebody else will fill that space and place you in an even more dangerous 14. Play spot the out-of-towner: these are the position people who drive even worse than Aucklanders 7. -

A Right to a Rite? the Blessing of Same-Sex Couples by the Anglican Church in New Zealand a Right to a Rite?®

A Right to a Rite? The Blessing of Same-sex Couples by the Anglican Church in New Zealand A Right to a Rite?® The Blessing of Same-sex Couples by the Anglican Church in New Zealand Abstract The Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia (ACANZP) and the worldwide Anglican Communion have become embroiled in the controversy surrounding the appropriateness of Same-sex Sexual Activity (SsSA) and Same-sex Sexual Relationship by Christians who desire to participate fully in the life of the Anglican Church. This controversy, which has aspects of an ideological war, has two primary fields of conflict - the Blessing of Committed Same-sex Couples (CSsC), and the consecration to the episcopacy of those involved in a CSsC relationship. This thesis will look at the first issue. The appeal for the ACANZP to Bless CSsC relationships is predicated on an un-stated and un-argued declaration that a CSsC relationship is, or can be, equivalent to a heterosexual couple joined in Holy Matrimony. This thesis takes the view that since the only relationship which the Anglican Church Blesses is a couple in or entering into Holy Matrimony, the request to Bless a CSsC couple must be argued on the basis of the equivalence of a CSsC relationship to Holy Matrimony. No other theology has been put forward to date. Some people may be predisposed towards experiencing relational, romantic or erotic attraction with some of their own sex, and perceive the experience of homosexual attraction as ‘natural’. The church need not ‘agree’ with this view in order to love, accept, and support those who experience such an attraction or are in such a relationship. -

True Crime New Zealand 2

1. TRUE CRIME NEW ZEALAND 2. TRUE CRIME NEW ZEALAND THE CASES: VOLUME ONE SIRIUS RUST SIRIUS PUBLISHING TRUE CRIME NEW ZEALAND 3. First published in 2019 Copyright © True Crime New Zealand Email: [email protected] Web: www.TrueCrimeNZ.com TRUE CRIME NEW ZEALAND 4. CONTENTS Introduction by Jessica Rust 6. History of True Crime New Zealand 9. Case 1: Parker-Hulme Murder, 1957, Christchurch 17. - Part I: Events Leading up to Murder 18. - Part II: Events Subsequent to Murder 49. Case 2: The Missing Swedes, 1989, Thames 67. - Prologue: A Trip of a Lifetime 68. - Investigation: Following Leads 82. - Epilogue: The Next Twenty Years 103. Case 3: Schlaepfer Family Murders, 1992, Paerata 122. Case 4: Delcelia Witika, 1991, Mangere 136. Case 5: Maketū Wharetōtara, 1842, Russell 154. Case 6: Minnie Dean, 1895, Winton 171. Case 7: Walter James Bolton, 1957, Wanganui 191. Case 8: Graeme Burton, 1992, Lower Hutt 210. - Part I: Paul Anderson 211. - Part II: Karl Kuchenbecker 223. Case 9: Joe Kum Yung, 1905, Wellington 249. Case 10: Brent Garner, 1996, Ashhurst 268. TRUE CRIME NEW ZEALAND 5. - Part I: Venus 270. - Part II: Mars 283. Case 11: The Crewe Murders, 1970, Pukekawa 294. - Prologue: Pukekawa 295. - Investigation: Looking for Evidence 310. - Epilogue: Nine Long Years 333. Case 12: The Rainbow Warrior, 1985, Auckland 356. - Prologue: Nuclear Proliferation 358. - Part I: Warriors of the Rainbow 365. - Part II: Operation Satanic 379. - Epilogue: Nuclear Free New Zealand 392. Aknowledgements 401. TRUE CRIME NEW ZEALAND 6. Introduction I met my husband in 2012. I was a lonely, insecure young woman. -

Ian Wishart Contents

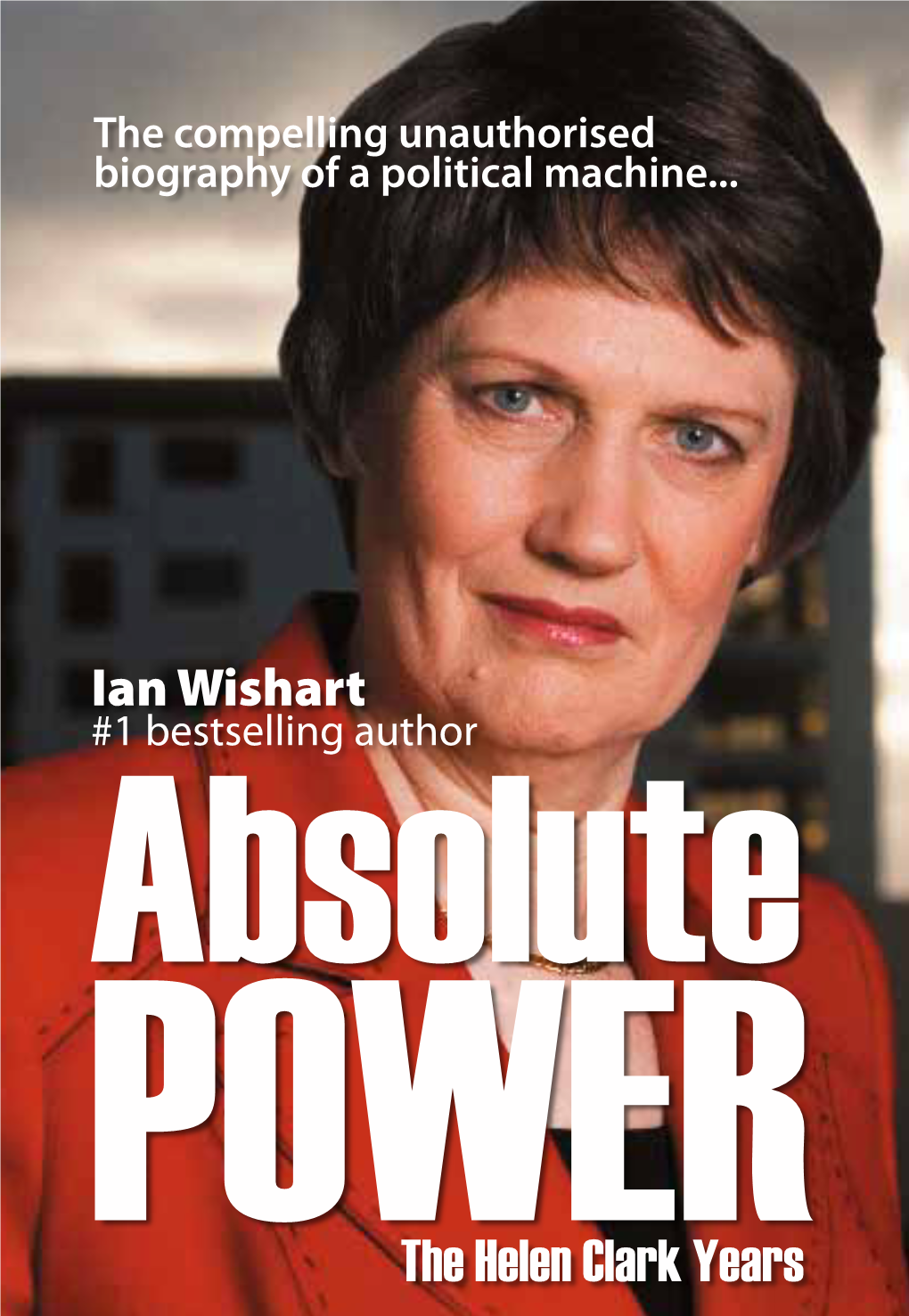

IAN W I S H A R T ANTHOLOGY Ian Wishart Contents Introduction Totalitaria Eve’s Bite Air Con Arthur Allan Thomas Ben & Olivia Missing Pieces Vitamin D Christ In The Crossfire The Paradise Conspiracy Lawyers, Guns & Money The Paradise Conspiracy II Daylight Robbery The Great Divide Our Stories Breaking Silence Winston Absolute Power Introduction Thanks for downloading Anthology, a series of extracts from a collection of my works. Every one of the books chosen for inclusion has been a bestseller. Five of them were national #1 bestsellers while many of the rest reached #2 or #3. Some of my books are not included because we restricted entries to currently available titles. For years people have asked for a written catalogue that contains a bit of information about each book. We’ve gone one better, making available a chapter or two of each so you can really get a feel for the books. Your local bookstore, anywhere in the world, can order any of these books in for you, or you can order them using the links at the end of each extract. As you’ll see, it’s been a long and varied career since the first title— The Paradise Conspiracy —was published back in 1995. In the space of 20 years I’ve covered big business scandals, murder mysteries, political biog- raphies, history, social issues, religion and climate change. Anthology is yours to review at your leisure, and free to pass on. —Ian Wishart, November 2015 TOTALITARIA IAN WISHART #1 BEstsELLinG AUthOR WHAT IF THE ENEMY IS THE STATE? Contents If You Have Nothing To Hide.. -

Fairfax NZ Ltd and Wilson Horton

PUBLIC VERSION Fairfax New Zealand Limited / Wilson & Horton Limited NOTICE SEEKING AUTHORISATION OR CLEARANCE OF A BUSINESS ACQUISITION PURSUANT TO S 67(1 ) OF THE COMMERCE ACT 1986 27 May 2016 The Registrar Business Acquisitions and Authorisations Commerce Commission PO Box 2351 WELLINGTON Pursuant to s 67(1) of the Commerce Act 1986 notice is hereby given seeking clearance , or in the alternative, authorisation , of a proposed business acquisition. PUBLIC VERSION 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 Wilson & Horton Limited (trading as " NZME ") and Fairfax NZ Limited (" Fairfax ") and their respective parent companies, APN News & Media Limited (" APN ") and Fairfax Media Limited (" Fairfax Media "), are seeking Commerce Commission approval to merge the New Zealand operations of NZME and Fairfax (the " Transaction "). 1.2 The decision by Fairfax and NZME (jointly, "the Parties" ) to merge is in response to the dramatically transforming media landscape. The media industry has been subject to exponential change over the last five years and this is set to continue, with print readership and revenue in decline and revenue from online news/information provision becoming highly competitive. The change has been particularly felt in New Zealand, where Internet penetration and smartphone ownership rates are among the highest in the world. 1.3 Over the past few years, NZME and Fairfax have both independently reshaped their businesses, and their traditional print publishing models, to respond to the modern media industry dynamics. These media dynamics started with the growth in popular use of the Internet, and the significant migration of classified advertising to websites such as Trade Me, but the pace of change has rapidly accelerated with the ubiquity of smartphones. -

Aspects of Helen Clark's Third Term Media Coverage

ANZCA08 Conference, Power and Place. Wellington, July 2008 Helengrad and other epithets: Aspects of Helen Clark’s third term media coverage Margie Comrie Massey University Margie Comrie is an Associate Professor in the Department of Communication Journalism and Marketing at Massey University where she teaches journalism studies and public relations. Her email address is [email protected] Abstract As New Zealand’s long-serving Prime Minister, Helen Clark, leads the Labour Party in its bid for an unprecedented fourth term in office, the nature of media coverage is crucial. This paper, while concentrating on Clark’s current term, reviews her relationship with the media over two decades. It discusses the gendered nature of reportage that continues to dog Clark, despite international recognition of her leadership. The paper argues that an often subtle gender bias in the media portrayal of Clark puts her at a disadvantage in the upcoming political contest with a younger male opponent. Introduction Nearing the end of an unprecedented third term of a Labour-led government, New Zealand Prime Minister Helen Clark dismisses the notion that gender is still an issue for her. Initially discounted as a woman with no leadership potential, she struggled her way to public acceptance and a protracted media honeymoon in her first term as prime minister. However, despite her eight years leading the country, Helen Clark’s gender remains a subtle disadvantage in the media as she faces a younger male opponent. Studies (e.g. Norris, 1997; Ross & Sreberny, 2000; Tuchman, 1978; van Zoonen, 2000) demonstrate that media reporting of female politicians is subject to gendered news frames and stereotypes that trivialise their contributions and handicap them in their quest for office. -

Investigate Magazine

Beating Big Brother IAN WISHARTS BESTSELLING NEW BOOK IS JUST OUT and PS, its about abolishing tax, and a fish from all good bookstores this summer, or check out the very special deal on our website: http://www.howlingatthemoon.com INVESTIGATE Jan/Feb 2001, 25 AGENT ORANGE: WE BURIED IT UNDER NEW PLYMOUTH As Investigate closes in on New Zealands biggest-ever toxic waste scandal, we now have hard evidence that a deadly herbicide used in the Vietnam War is buried under part of New Plymouth city. IAN WISHART and SIMON JONES provide team coverage: 26, INVESTIGATE Jan/Feb 2001 former top official at New Plymouths Ivon Watkins Dow case for the need to defoliate the jungle, because of the chemical factory has confirmed the worst fears of resi- risk to servicemen from ambush or sniper fire from the dents part of the town may be sitting on a secret toxic undergrowth. waste dump containing the deadly Vietnam War defoli- So we began manufacturing this Agent Orange, but it ant Agent Orange. didnt meet the international specifications and probably The official, who has proven his identity and executive had an excess of nasties in it. The problem was, we didnt ranking in documents provided to Investigate, says the consider the product was harmful to humans at the time. company owned a large piece of land very close to the Our scientists relied on assurances and technical data chemical plant, which we called the Experimental Farm. provided to them by Dow Chemicals in the USA. We were We bulldozed big pits and dumped thousands of tonnes led to believe it was safe.