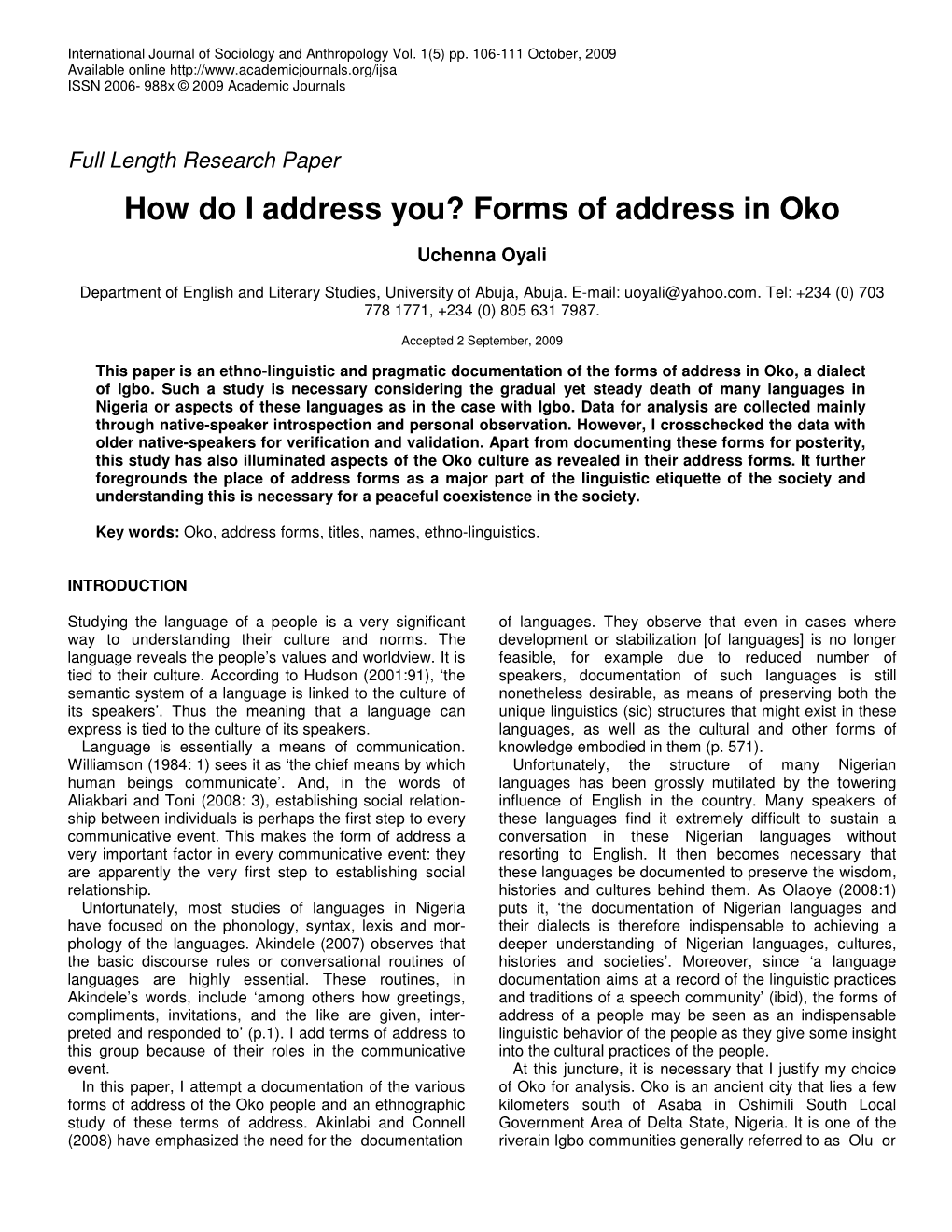

Forms of Address in Oko

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Land Has Changed: History, Society and Gender in Colonial Eastern Nigeria

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2010 The land has changed: history, society and gender in colonial Eastern Nigeria Korieh, Chima J. University of Calgary Press Chima J. Korieh. "The land has changed: history, society and gender in colonial Eastern Nigeria". Series: Africa, missing voices series 6, University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2010. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/48254 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com THE LAND HAS CHANGED History, Society and Gender in Colonial Eastern Nigeria Chima J. Korieh ISBN 978-1-55238-545-6 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

ESTABLISHMENT of STRATEGIES for IMPROVING AFFORDABLE and HABITABLE PUBLIC HOUSING PROVISION in ANAMBRA STATE, NIGERIA Eni, Chika

British Journal of Environmental Sciences Vol.3, No.1, pp.23-42, March 2015 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajouirnals.org) ESTABLISHMENT OF STRATEGIES FOR IMPROVING AFFORDABLE AND HABITABLE PUBLIC HOUSING PROVISION IN ANAMBRA STATE, NIGERIA Eni, Chikadibia Michael (Arc., Dr.) Department of Architectural-Technology, Federal Polytechnic, Oko. P.M.B. 021, Aguata, Anambra State, Nigeria ABSTRACT: This view of this study was based on the establishment of strategies for improving affordable and habitable public housing provision in Anambra state, Nigeria. This study utilized a survey research design in the collection of data. The universe of study consisted of 2,805 occupants comprising mainly households, and 2,805 house units, comprising 1,032 in Awka city and 1,773 in Onitsha city. The sample size of 30% (842) was used as derived from Taro Yamani technique. A stratified random sampling of these disparate public housing estates based on their proportion to population was studied. A 16-item structured questionnaire on establishment of strategies for improving affordable and habitable public housing provision in Anambra state, Nigeria (QSAHPH) was developed. This instrument was face and content validated. Cronbach Alpha Technique index was used for reliability test which gave a value of 0.90. The data were obtained by pulling all positive responses for each group of occupants (Awka or Onitsha) as positive responses and as negative responses and their proportions obtained and filled below pooled observations (counts). Undecided responses were left as neutral. Complete responses were 797 comprising 299 occupants in Awka and 498 occupants in Onitsha. -

Terms of Reference for Consultant Services in Accordance with the EITI Standard

APPENDIX 1.2 - TERMS OF REFERENCE Terms of Reference for Consultant services in accordance with the EITI Standard 2013 OIL & GAS AUDIT TERMS OF REFERENCE (SCOPE OF WORK) Consultancy for the 2013 EITI Report - Nigeria Approved by the NSWG on 11th December 2013 1. BACKGROUND The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) is a global standard that promotes revenue transparency and accountability in the oil, gas and mining sectors. It has a robust yet flexible methodology for disclosing and reconciling company payments and government revenues in implementing countries. The EITI process may be extended and adapted to meet the information needs of stakeholders. EITI implementation has two core components: • Transparency: oil, gas and mining companies disclose their payments to the government, and the government discloses its receipts. The figures are reconciled by a Consultant, and published in annual EITI Reports alongside contextual information about the oil and gas sector. • Accountability: a multi-stakeholder group with representatives from government, companies and civil society is established to oversee the process and communicate the findings of the EITI Report. It is a requirement that the Consultant is perceived by the multi-stakeholder group to be credible, trustworthy and technically competent (Requirement 5.1). The Consultant’s report will be submitted to the NSGW for approval and made publically available. The requirements for implementing countries are set out in the EITI Standard1. Additional information is available via www.eiti.org By the EITI rules, implementing countries are required to publish their annual reports for the period not later than two preceding years. The Oil and Gas Industry Audit 2013 Report must be published by the end of the 2014 to ensure Nigeria meets the EITI Standard. -

PARADOX of REALITIES in the 20 – POUNDS SAGA Exposes the Impact of the Pre & Post War-Time Polices of Obafemi Awolowo on Igbos: 1

IGBO & OBAFEMI AWOLOWO: THE PARADOX OF REALITIES IN THE 20 – POUNDS SAGA exposes the impact of the Pre & Post war-time Polices of Obafemi Awolowo On Igbos: 1. Blockade of Bakassi Peninsula, 2. Change of Currency 3. and 20 – Pounds Sega. READ it from the INTERNET: OPEN to Goggles or Nigerian Voice.com, Queue in Kindness Innocent Jonah on “Igbos & Obafemi Awolowo: The Paradox of Realities”. PRINT OUT, READ THOROUGHLY, then: PURCHASE IT FOR ONE THOUSAND NAIRA (N1, 000 ONLY), for You and Your Generation, for KEEPS, for what truelly happened to Igbos in the War between 1966 – 1976: The Dangerous Decade of Igbo History. After Reading through, Go to any Branch of ACCESS BANK and PAY IN TO: Kindness Innocent Jonah 002 – 9414 – 774 (The Author) If this Book has Blessed Your Historical Memory, please, please and please, BE FAITHFULLY TO PAY for this knowledge, though no one compels you to pay. I want you to read it first before paying, and that is why I posted it for Public Consumption First. But remember it is a Book with ISBN: 978 – 8032 – 78 – 8 Knowledge is costly, please note. Best Regards from the Author, Comrade Kindness Innocent Jonah 080-3666-2901, 080-9595-7698 i IGBOS AND OBAFEMI AWOLOWO: PARADOX OF REALITIES IN THE 20 – POUNDS SAGA A Book that analyses Chinua Achebe’s recent comment on the impact of Awolowo’s War Policies on Igbos, will be presented to the August Body of Igbo intelligentsia. Innocent J.K.O. (Innocent Jonah Kindness O.) President of a Human Rights Group: ROMKEEP: Rights of Man Keep. -

MINISTERIUM - Journal of Contextual Theology Published by Blessed Iwene Tansi Major Seminary, Onitsha, Anambra State, Nigeria

MINISTERIUM - Journal of Contextual Theology Published by Blessed Iwene Tansi Major Seminary, Onitsha, Anambra State, Nigeria VOLUME 1 MAIDEN EDITION JUNE, 2014 EDITORIAL BOARD Editor Peter O. Okafor Blessed Iwene Tansi Major Seminary, Onitsha, Nigeria Deputy Editor Vitalis Anaehobi Blessed Iwene Tansi Major Seminary, Onitsha, Nigeria Members Elochukwu E. Uzukwu, C.S.Sp. Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, USA Gregory Nwachukwu Blessed Iwene Tansi Major Seminary, Onitsha, Nigeria Christopher I. Ejizu University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria Paulinus Odozor, C.S.Sp. University of Notre Dame, Indiana, USA Uchenna A. Eze Blessed Iwene Tansi Major Seminary, Onitsha, Nigeria Francis Oborji Pontifical Urban University, Rome Editorial Assistants Cletus O. Ekwosi & Fidelis Izuakor Blessed Iwene Tansi Major Seminary, Onitsha, Nigeria Editorial Consultant Peter Damian Akpunonu Villa Mount Carmel, Onitsha, Nigeria EDITORIAL Peter O. Okafor History is at last made. Blessed Iwene Tansi Major Seminary, Onitsha offers the academic world and the reading public the maiden edition of her theological journal titled Ministerium - Journal of Contextual Theology. The brand of theology that she offers is known as contextual theology which is a theology based on the understanding that the context where theology is happening is determinative. This theological perspective thrives on the assumption that a genuine theology is articulated with reference to or dependent on the events, the thought forms, or the culture of its particular place and time. In embarking on this onerous theological project, we believe that there are three main sources of such a theology, namely, scripture, tradition and concrete human experience in a particular culture and society. By focusing on contextualization of theology, this journal offers not only to Africa but to the entire world a forum for a theology that is relevant and up to date according to different contexts. -

Validating Perceptual Objective Listening Quality Assessment Methods on the Tonal Language Igbo

Faculty of Electrical Engineering, Mathematics and Computer Science Network Architectures and Services Validating Perceptual Objective Listening Quality Assessment Methods on the tonal Language Igbo. EBEM, DEBORAH UZOAMAKA (1388312) Committee members:Prof.Dr.Ir.P.F.A van Meighem Dr. Richards Heusdens Dr.Ir.J.Weber Supervisor: Dr.Ir.R.E.Kooij Mentor 1: Ir.J.M.van Vugt Mentor 2:Dr.Ir.J.G.Beerends 3rd June, 2009 M.Sc. Thesis No: PVM 2009 – 053 Copyright ©2009 by D.U.Ebem All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the permission from the author and Delft University of Technology. 1 Acknowledgement First of all, I would like to appreciate my supervisor Dr.Ir. R.E.Kooij and my mentors Ir. J.M.van Vugt and Dr. Ir. J.G.Beerends for their commitment, consistency and excellent supervision throughout the period of this thesis. Secondly, I am greatly indebted to the native Igbo speakers (Charles Oragui, Ogechi Agbo and Samuel Ani) and the subjects who participated in the subjective experiment for their time, understanding and patience . I am equally grateful to the management of TNO for giving me the opportunity to do a thesis work in their company. I also would like to thank Mathilde Miedema, head of the TNO programme Innovation in Development for financing my field trip to Nigeria. Also Dr Ir Nicholas Chevrollier and Dr. Ir. F.A. -

Social Capital and Household Welfare Among Anioma People in Delta State, Nigeria

Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal – Vol.6, No.3 Publication Date: Mar. 25, 2019 DoI:10.14738/assrj.63.6262. Onyemenam, C. E. (2019). Social Capital and Household Welfare Among Anioma People in Delta State, Nigeria. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 6(3) 159-182. Social Capital and Household WelFare Among Anioma People in Delta State, Nigeria Dr. Chris ‘E Onyemenam Lecturer, Department Of Sociology And Anthropology Baze University, Abuja, Nigeria ABSTRACT Most studies on social capital and household welFare have Focused largely on econometric analyses oF Formal networks while inFormal, less institutionalised but durable networks are either ignored or concepts like ‘trust’, and ‘age groups’ are reduced to equations in econometric models that leaves out the quintessential social aspects. This non-econometric study Focused on inFormal networks and social relations, using ethnographic and cross-sectional survey data From 13 homogenous Anioma communities in Delta State, Nigeria. Descriptive and inFerential statistics were used to analyse the primary data while content analysis was used For the ethnographic data. Among others, the study Found that access to social capital was not gender sensitive, it was not signiFicantly related to welfare but it is positively correlated with household per capita income. Finally, while there was a large stock of social capital, household welFare remained low, due to the high level oF poverty and the inFluence oF the communal value that places an obligation on those who have more than others to help, such that they become ‘drawn back’, by their stock oF social capital, which becomes an encumbrance oF a kind. -

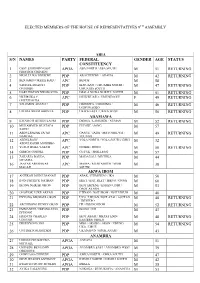

List of the Elected House of Representatives Members for the 9Th Assembly

ELECTED MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 9TH ASSEMBLY ABIA S/N NAMES PARTY FEDERAL GENDER AGE STATUS CONSTITUENCY 1 OSSY EHIRIODO OSSY APGA ABA NORTH / ABA SOUTH M 51 RETURNING PRESTIGE CHINEDU 2 NKOLE UKO NDUKWE PDP AROCHUKWU / OHAFIA M 42 RETURNING 3 BENJAMIN OKEZIE KALU APC BENDE M 58 4 SAMUEL IFEANYI PDP IKWUANO / UMUAHIA NORTH / M 47 RETURNING ONUIGBO UMUAHIA SOUTH 5 DARLINGTON NWOKOCHA PDP ISIALA NGWA NORTH / SOUTH M 51 RETURNING 6 NKEIRUKA C. APC ISUIKWUATO / UMUNEOCHI F 49 RETURNING ONYEJEOCHA 7 SOLOMON ADAELU PDP OBINGWA / OSISIOMA / M 46 RETURNING UGWUNAGBO 8 UZOMA NKEM ABONTA PDP UKWA EAST / UKWA WEST M 56 RETURNING ADAMAWA 9 KWAMOTI BITRUS LAORI PDP DEMSA / LAMURDE / NUMAN M 52 RETURNING 10 MUHAMMED MUSTAFA PDP FUFORE / SONG M 57 SAIDU 11 ABDULRAZAK SA’AD APC GANYE / JADA / MAYO BELWA / M 49 RETURNING NAMDAS TOUNGO 12 ABDULRAUF APC YOLA NORTH / YOLA SOUTH/ GIREI M 32 ABDULKADIR MODIBBO 13 YUSUF BUBA YAKUB APC GOMBI / HONG M 50 RETURNING 14 GIBEON GOROKI PDP GUYUK / SHELLENG M 57 15 ZAKARIA DAUDA PDP MADAGALI / MICHIKA M 44 NYAMPA 16 JAAFAR ABUBAKAR APC MAIHA / MUBI NORTH / MUBI M 38 MAGAJI SOUTH AKWA IBOM 17 ANIEKAN JOHN UMANAH PDP ABAK / ETIM EKPO / IKA M 50 18 IFON PATRICK NATHAN PDP EKET / ESIT EKET / IBENO / ONNA M 60 19 IKONG NSIKAK OKON PDP IKOT EKPENE / ESSIEN UDIM / M 53 OBOT AKARA 20 ONOFIOK LUKE AKPAN PDP ETINAN / NSIT IBOM / NSIT UBIUM M 40 21 ENYONG MICHAEL OKON PDP UYO / URUAN /NSIT ATAI / ASUTAN M 48 RETURNING / IBESIKPO 22 ARCHIBONG HENRY OKON PDP ITU /IBIONO IBOM M 52 RETURNING 23 EMMANUEL UKPONG-UDO -

Dynamics of Pre-Colonial Diplomatic Practices Among the Igbo Speaking People of Southeastern Nigeria, 1800-1900: a Historical Evaluation

Historical Research Letter www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3178 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0964 (Online) Vol.43, 2017 DYNAMICS OF PRE-COLONIAL DIPLOMATIC PRACTICES AMONG THE IGBO SPEAKING PEOPLE OF SOUTHEASTERN NIGERIA, 1800-1900: A HISTORICAL EVALUATION Patrick Okpalaeke Chukwudike 1 Esin Okon Eminue 2 1. Department of History and International Studies, University of Uyo, Uyo. Nigeria 2. Department of History and International Studies, University of Uyo, Uyo, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper seeks to conduct a historical evaluation on the dynamics of pre-colonial diplomatic relations among the Igbo speaking people of Southeastern Nigerian. This became a necessity owing to the fact that there appear to be a big neglect by scholars of Igbo descent in discussing the mode by which city-states littered across the Southeastern region of Nigeria conducted their own unique form of diplomacy. This implication of this neglect have only given further credence to Eurocentric claims that “Africa has no history”. It is a historical fact that when most societies where invaded by European colonialists, they paid little or no attention to how these societies have conducted indigenous affairs that have for centuries sustained them. Rather, a conclusion was drawn that these pre-colonial societies were devoid of any meaningful aspect of life that should be understudied. Be that as it may, through the concept of African historiography, the fore-going has long been debunked with the help of oral history as enunciated by Jan Vasina. However, what is yet to receive adequate attention is the art of diplomacy across Africa, vis a vis the conduct of diplomatic practices among the Igbo speaking people of Southeast Nigeria .Thus, the study reveals base on the much available sources, that in pre-colonial Igboland, the people conducted a unique and sophisticated art of diplomacy. -

Customary Land Rights and Gender Justice in Eastern Nigeria and Ghana

CUSTOMARY LAND RIGHTS AND GENDER JUSTICE IN EASTERN NIGERIA AND GHANA NELSON O. MADUMERE A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of East London for the degree of PhD in Law School of Business and Law September 2018 i ABSTRACT Common approaches to the challenges of tenure discrimination and inequitable land administration system in Nigerian centres on the adoption of statutory legal propositions and judicial proscriptions for the achievement of the desired goals. This entails the adoption and elevation of conventional land administration principles as the ultimate standard for evaluating all other tenurial and land administration systems in Nigeria. The continued existence of these challenges and emergence of fresh constraints clearly underscore the ineffectiveness of the policy choices and preferred administrative responses to the achievement of desired goals, and the continued reliance on these approaches alone risk marginalising further the voices of local communities, especially women. In the case of the Igbos of the Eastern Nigeria, this results in failure to address the systemic challenges of tenure insecurity, rural poverty, unsustainable development and continued existence of various outlawed discriminatory customary practices that disinherit and subjugate women. Even the recent Supreme Court’s intervention makes negligible impacts as most of these proscribed practices continue to enjoy social legitimacy and remain operational secretly. Drawing from the outcomes of the recent Ghanaian reform experiences, this thesis looks at the prospects for reformation and statutory recognition of customary tenure system in Eastern Nigeria using the principles of “Responsible Land Management”, “Fit-for- purpose (FFP)”, “Continuum of land-rights” and “Social Tenure Domain Model (STDM)” land tools. -

Nigerian Writers

Society of Young Nigerian Writers Chris Abani From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search Chris Abani The poem "Ode to Joy" on a wall in the Dutch city of Leiden Christopher Abani (or Chris Abani) (born 27 December 1966) is a Nigerian author. He is part of a new generation of Nigerian writers working to convey to an English-speaking audience the experience of those born and raised in "sthat troubled African nation". Contents 1 Biography 2 Education and career 3 Published works 4 Honors and awards 5 References 6 External links Biography Chris Abani was born in Afikpo, Nigeria. His father was Igbo, while his mother was English- born.[1] He published his first novel, Masters of the Board (1985) at the age of sixteen. The plot was a political thriller and it was an allegory for a coup that was carried out in Nigeria just before it was written. He was imprisoned for 6 months on suspicion of an attempt to overthrow the government. He continued to write after his release from jail, but was imprisoned for one year after the publication of his novel, Sirocco. (1987). After he was released from jail this time, he composed several anti-government plays that were performed on the street near government offices for two years. He was imprisoned a third time and was placed on death row. Luckily, his friends had bribed government officials for his release in 1991, and immediately Abani moved to the United Kingdom, living there until 1999. He then moved to the United States, where he now lives.[2] Material parts of his biography as it relates to his alleged political activism, imprisonments and death sentence in Nigeria have been disputed as fiction by some Nigerian literary activists of the period in question. -

PART I Essays

PART I Essays Post-War Reintegration, Reconstruction and Reconciliation Among the Anioma People of Nigeria Odigwe A. Nwaokocha Abstract Much has been written on the Nigerian Civil War. However, its impact on some minority groups has been largely neglected. This oversight has affected scholarly treatment of how forces emanating from the war impacted the Anioma people. Though predominantly Igbo-speaking, the Anioma were geographically on the Nigerian side during the war. The dynamics of the war as an ethnic conflict ensured that Aniomaland was a major battlefront. At the end of the war, the Anioma were a distressed group. Houses, homes, careers, dreams, aspirations and individuals lay in ruins. This left the people and their territory in need of major rehabilitation. This article focuses on the rehabilitation and reintegration of the Anioma into the society. It attempts this against the background of the Nigerian government’s policy of rehabilitation and the trumpeted principle of “no victor, no vanquished,” which dominates discourses on the war. Employing primary and secondary sources, the work probes how the Anioma people fared under the post-war rehabilitation program at different levels. It argues that it was difficult for the Nigerian government and society to completely forget the bitterness of the war even while implementing the rehabilitation program. This left the program struggling to manage two diametrically opposed principles, resulting in its merely scratching the surface after promising much. The Anioma occupy a unique place in the history of the Nige- rian Civil War (1967-1970), a conflict that pitched the Igbo group of the former Eastern Region against Nigeria.