Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flood Vulnerability Assessment of Afikpo South Local Government Area, Ebonyi State, Nigeria

International Journal of Environment and Climate Change 9(6): 331-342, 2019; Article no.IJECC.2019.026 ISSN: 2581-8627 (Past name: British Journal of Environment & Climate Change, Past ISSN: 2231–4784) Flood Vulnerability Assessment of Afikpo South Local Government Area, Ebonyi State, Nigeria Endurance Okonufua1*, Olabanji O. Olajire2 and Vincent N. Ojeh3 1Department of Road Research, Nigerian Building and Road Research Institute, Ota, Ogun State, Nigeria. 2African Regional Centre for Space Science and Technology Education in English, OAU and Centre for Space Research and Applications, Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria. 3Department of Geography, Taraba State University, P.M.B. 1167, Jalingo, Nigeria. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration among all authors. Authors EO, OOO and VNO designed the study, performed the statistical analysis, wrote the protocol and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors OOO and VNO managed the analyses of the study. Author EO managed the literature searches. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/IJECC/2019/v9i630118 Editor(s): (1) Dr. Anthony R. Lupo, Professor, Department of Soil, Environmental and Atmospheric Science, University of Missouri, Columbia, USA. Reviewers: (1) Ionac Nicoleta, University of Bucharest, Romania. (2) Neha Bansal, Mumbai University, India. (3) Abdul Hamid Mar Iman, Universiti Malaysia Kelantan, Malaysia. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sdiarticle3.com/review-history/48742 Received 26 March 2019 Accepted 11 June 2019 Original Research Article Published 18 June 2019 ABSTRACT The study was conducted in Afikpo South Local Government covering a total area of 331.5km2. Remote sensing and Geographic Information System (GIS) were integrated with multicriteria analysis to delineate the flood vulnerable areas. -

95 Traditional Methods of Social Control in Afikpo

TRADITIONAL METHODS OF SOCIAL CONTROL IN AFIKPO NORTH LOCAL GOVERNMENT AREA, EBONYI STATE SOUTH EASTERN NIGERIA Blessing Nonye Onyima Abstract This paper examined the traditional social control mechanisms in Afikpo North LGA of Ebonyi state, south eastern Nigeria. The rising trend in extraneous crimes and vices like kidnapping, baby factories, drug peddling among others seem to be overwhelming for modern social control mechanisms. This has lent credence to myriads of scholarly suggestions targeted towards making the south eastern Nigerian region a sane society. These suggestions are community policing, use of community vigilante and calls to integrating traditional and modern social control mechanisms. This study employed I86 structured questionnaires and the in-depth interview guide as instruments for data collection anchored on the social bond theory. The researcher made use of descriptive statistics to analyze the questionnaires, the frequency tables and simple percentage was used in presenting and interpreting the quantitative data. The data was also processed using the SPSS, for detailed analysis of the questionnaire. The qualitative data from the in-depth interview was analyzed using the manual thematic content analysis. The study found two groups of effective traditional social control methods (human and non-human traditional social control methods) used to ensure social cohesiveness, order and peaceful inter-human relations in Afikpo North LGA of Ebonyi state. Study respondents expressed preference for human- oriented/managed -

Bible Translation and Language Elaboration: the Igbo Experience

Bible Translation and Language Elaboration: The Igbo Experience A thesis submitted to the Bayreuth International Graduate School of African Studies (BIGSAS), Universität Bayreuth, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Dr. Phil.) in English Linguistics By Uchenna Oyali Supervisor: PD Dr. Eric A. Anchimbe Mentor: Prof. Dr. Susanne Mühleisen Mentor: Prof. Dr. Eva Spies September 2018 i Dedication To Mma Ụsọ m Okwufie nwa eze… who made the journey easier and gave me the best gift ever and Dikeọgụ Egbe a na-agba anyanwụ who fought against every odd to stay with me and always gives me those smiles that make life more beautiful i Acknowledgements Otu onye adịghị azụ nwa. So say my Igbo people. One person does not raise a child. The same goes for this study. I owe its success to many beautiful hearts I met before and during the period of my studies. I was able to embark on and complete this project because of them. Whatever shortcomings in the study, though, remain mine. I appreciate my uncle and lecturer, Chief Pius Enebeli Opene, who put in my head the idea of joining the academia. Though he did not live to see me complete this program, I want him to know that his son completed the program successfully, and that his encouraging words still guide and motivate me as I strive for greater heights. Words fail me to adequately express my gratitude to my supervisor, PD Dr. Eric A. Anchimbe. His encouragements and confidence in me made me believe in myself again, for I was at the verge of giving up. -

History of Seventh-Day Adventist Church in Igboland (1923 – 2010 )

NJOKU, MOSES CHIDI PG/Ph.D/09/51692 A HISTORY OF SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH IN IGBOLAND (1923 – 2010 ) FACULTY OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION Digitally Signed by : Content manager’s Name Fred Attah DN : CN = Webmaster’s name O= University of Nigeri a, Nsukka OU = Innovation Centre 1 A HISTORY OF SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST CHURCH IN IGBOLAND (1923 – 2010) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF RELIGION AND CULTURAL STUDIES, FACULTY OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE AWARD OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D) DEGREE IN RELIGION BY NJOKU, MOSES CHIDI PG/Ph.D/09/51692 SUPERVISOR: REV. FR. PROF. H. C. ACHUNIKE 2014 Approval Page 2 This thesis has been approved for the Department of Religion and Cultural Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka By --------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Rev. Fr. Prof. H. C. Achunike Date Supervisor -------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ External Examiner Date Prof Musa Gaiya --------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Internal Examiner Date Prof C.O.T. Ugwu -------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Internal Examiner Date Prof Agha U. Agha -------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Head of Department Date Rev. Fr. Prof H.C. Achunike --------------------------------------------- ------------------------------ Dean of Faculty Date Prof I.A. Madu Certification 3 We certify that this thesis -

Igbo Folktales and the Idea of Chukwu As Supreme God of Igbo Religion Chukwuma Azuonye, University of Massachusetts Boston

University of Massachusetts Boston From the SelectedWorks of Chukwuma Azuonye April, 1987 Igbo Folktales and the Idea of Chukwu as Supreme God of Igbo Religion Chukwuma Azuonye, University of Massachusetts Boston Available at: http://works.bepress.com/chukwuma_azuonye/76/ ISSN 0794·6961 NSUKKAJOURNAL OF LINGUISTICS AND AFRICAN LANGUAGES NUMBER 1, APRIL 1987 Published by the Department of Linguistics and Nigerian Languages, University of Nigeria, Nsukka NOTES ON THE CONTRIBUTORS All but one of the contributors to this maiden issue of The Nsukka Journal of Linguistics and African Languages are members of the Department of Linguistics and Nigerian Languages, Univerrsity of Nigeria, Nsukka Mr. B. N. Anasjudu is a Tutor in Applied Linguistics (specialized in Teaching English as a Second Language). Dr. Chukwuma Azyonye is a Senior Lecturer in Oral Literature and Stylistics and Acting Head of Department. Mrs. Clara Ikeke9nwy is a Lecturer in Phonetics and Phonology. Mr. Mataebere IwundV is a Senior Lecturer in Sociolinguistics and Psycholinguistics. Mrs. G. I. Nwaozuzu is a Graduate Assistant in Syntax and Semantics. She also teaches Igbo Literature. Dr. P. Akl,ljYQQbi Nwachukwu is a Senior Lecturer in Syntax and Semantics. Professor Benson Oluikpe is a Professor of Applied and Comparative Linguistics and Dean of the Faculty of Arts. Mr. Chibiko Okebalama is a Tutor in Literature and Stylistics. Dr. Sam VZ9chukwu is a Senior Lecturer in Oral Literature and Stylistics in the Department of African Languages and Literatures, University of Lagos. ISSN 0794-6961 Nsukka Journal of L,i.nguistics and African Languages Number 1, April 1987 IGBD FOLKTALES AND THE EVOLUTION OF THE IDEA OF CHUKWU AS THE SUPREME GOD OF IGBO RELIGION Chukwuma Azyonye This analysis of Igbo folktales reveals eight distinct phases in the evolution of the idea of Chukwu as the supreme God of Igbo religion. -

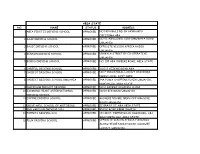

Abia State No

ABIA STATE NO. NAME STATUS ADDRESS 1 ABIA FIRST II DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO 140 UMULE RD. BY UKWUAKPU OSISIOMA ABA. 2 AJAE DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO 53 AWOLOWO SGBY UMUWAYA ROAD UMUAHIA 3 BASIC DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED OPPOSITE VISION AFRICA RADIO UMUAHIA 4 BENSON DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED UBAKALA STREET BY CO-OPERATIVE UMUAHIA 5 BOBOS DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO. 105 ABA OWEERI ROAD, ABIA STATE 6 CAREFUL DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED 111/113 AZIKWE ROAD ABA 7 CHIBEST DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO 7 INDUSTRIAL LAYOUT OSISIOMA NGWA LOCAL GOVT AREA 8 CHIBEST DRIVING SCHOOL UMUAHIA APPROVED 34A POWA SHOPPING PLAZA UMUAHIA, NORTH LGA, ABIA STATE 9 CHINEDUM PRIVATE DRIVING APPROVED NO 2 AZIKWE OCHENDU CLOSE 10 DIAMOND HEART INTERNATIONAL APPROVED NO.10 BCA ROAD UMUAHIA DRIVING SCHOOL 11 DIVINE DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED AHIAEKE NDUME IBEKU OFF UMUSIKE ROAD UMUAHIA 12 DRIVE-WELL SCHOOL OF MOTORING, APPROVED 27 BRASS ST. ABA ABIA STATE. 13 ENG AMOSON DRIVING SCH APPROVED 95 FGC ROAD EBEM OHAFIA 14 EXPERTS DRIVING SCH APPROVED 133 IKOT- EKPENE ROAD OGBORHILL ABA, ABA NORTH LGA, ABIA STATE. 15 FLUX DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED OPPOSITE VISION AFRICA F.M RADIO ALONG SECRETARIAT ROAD, OGURUBE LAYOUT UMUAHIA 16 GIVENCHY DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO 60 WARRI BY BENDER ROAD UMUAHIA, ABIA STATE. 17 HALLMARK DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED SUITE 4, 44-55 OSINULO SHOPPING COMPLEX ISI COURT UMUOBIA OLOKORO, UMUAHIA, ABIA STATE 18 IFEANYI DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED AMAWOM OBORO IKWUANO LGA 19 IJEOMA DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO.3 CHECHE CLOSE AMANGWU, OHAFIA, ABIA STATE 20 INTERNATIONAL DRIVING SCHOOL APPROVED NO. 2 MECHANIC LAYOUT OFF CLUB ROAD UMUAHIA. -

Historical Dynamics of Ọjị Ezinihitte Cultural Festival in Igboland, Nigeria

67 International Journal of Modern Anthropology Int. J. Mod. Anthrop. 2020. Vol. 2, Issue 13, pp: 67 - 98 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ijma.v2i13.2 Available online at: www.ata.org.tn & https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ijma Research Article Historical dynamics of Ọjị Ezinihitte cultural festival in Igboland, Nigeria Akachi Odoemene Department of History and International Studies, Federal University Otuoke, Bayelsa State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] (Received 6 January 2020; Accepted 16 May 2020; Published 6 June 2020) Abstract - Ọjị (kola nut) is indispensable in traditional life of the Igbo of Nigeria. It plays an intrinsic role in almost all segments of the people‟s cultural life. In the Ọjị Ezinihitte festivity the „kola tradition‟ is meaningfully and elaborately celebrated. This article examines the importance of Ọjị within the context of Ezinihitte socio-cultural heritage, and equally accounts for continuity and change within it. An eclectic framework in data collection was utilized for this research. This involved the use of key-informant interviews, direct observation as well as extant textual sources (both published and un-published), including archival documents, for the purposes of the study. In terms of analysis, the study utilized the qualitative analytical approach. This was employed towards ensuring that the three basic purposes of this study – exploration, description and explanation – are well articulated and attained. The paper provided background for a proper understanding of the „sacred origin‟ of the Ọjị festive celebration. Through a vivid account of the festival‟s processes and rituals, it achieved a reconstruction of the festivity‟s origins and evolutionary trajectories and argues the festival as reflecting the people‟s spirit of fraternity and conviviality. -

Ph.D Thesis-A. Omaka; Mcmaster University-History

MERCY ANGELS: THE JOINT CHURCH AID AND THE HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE IN BIAFRA, 1967-1970 BY ARUA OKO OMAKA, BA, MA A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Ph.D. Thesis – A. Omaka; McMaster University – History McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2014), Hamilton, Ontario (History) TITLE: Mercy Angels: The Joint Church Aid and the Humanitarian Response in Biafra, 1967-1970 AUTHOR: Arua Oko Omaka, BA (University of Nigeria), MA (University of Nigeria) SUPERVISOR: Professor Bonny Ibhawoh NUMBER OF PAGES: xi, 271 ii Ph.D. Thesis – A. Omaka; McMaster University – History ILLUSTRATIONS Figures 1. AJEEBR`s sponsored advertisement ..................................................................122 2. ACKBA`s sponsored advertisement ...................................................................125 3. Malnourished Biafran baby .................................................................................217 Tables 1. WCC`s sickbays and refugee camp medical support returns, November 30, 1969 .....................................................................................................................171 2. Average monthly deliveries to Uli from September 1968 to January 1970.........197 Map 1. Proposed relief delivery routes ............................................................................208 iii Ph.D. Thesis – A. Omaka; McMaster University – History ABSTRACT International humanitarian organizations played a prominent role -

Igbo Man's Belief in Prayer for the Betterment of Life Ikechukwu

Igbo man’s Belief in Prayer for the Betterment of Life Ikechukwu Okodo African & Asian Studies Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka Abstract The Igbo man believes in Chukwu strongly. The Igbo man expects all he needs for the betterment of his life from Chukwu. He worships Chukwu traditionally. His religion, the African Traditional Religion, was existing before the white man came to the Igbo land of Nigeria with his Christianity. The Igbo man believes that he achieves a lot by praying to Chukwu. It is by prayer that he asks for the good things of life. He believes that prayer has enough efficacy to elicit mercy from Chukwu. This paper shows that the Igbo man, to a large extent, believes that his prayer contributes in making life better for him. It also makes it clear that he says different kinds of prayer that are spontaneous or planned, private or public. Introduction Since the Igbo man believes in Chukwu (God), he cannot help worshipping him because he has to relate with the great Being that made him. He has to sanctify himself in order to find favour in Chukwu. He has to obey the laws of his land. He keeps off from blood. He must not spill blood otherwise he cannot stand before Chukwu to ask for favour and succeed. In spite of that it can cause him some ill health as the Igbo people say that those whose hands are bloody are under curses which affect their destines. The Igboman purifies himself by avoiding sins that will bring about abominations on the land. -

The Influence of the Supernatural in Elechi Amadi’S the Concubine and the Great Ponds

THE INFLUENCE OF THE SUPERNATURAL IN ELECHI AMADI’S THE CONCUBINE AND THE GREAT PONDS BY EKPENDU, CHIKODI IFEOMA PG/MA/09/51229 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND LITERARY STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA. SUPERVISOR: DR. EZUGU M.A A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF ARTS (M.A) IN ENGLISH & LITERARY STUDIES TO THE SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA. JANUARY, 2015 i TITLE PAGE THE INFLUENCE OF THE SUPERNATURAL IN ELECHI AMADI’S THE CONCUBINE AND THE GREAT PONDS BY EKPENDU, CHIKODI IFEOMA PG /MA/09/51229 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH & LITERARY STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA. JANUARY, 2015 ii CERTIFICATION This research work has been read and approved BY ________________________ ________________________ DR. M.A. EZUGU SIGNATURE & DATE SUPERVISOR ________________________ ________________________ PROF. D.U.OPATA SIGNATURE & DATE HEAD OF DEPARTMENT ________________________ ________________________ EXTERNAL EXAMINER SIGNATURE & DATE iii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my dear son Davids Smile for being with me all through the period of this study. To my beloved husband, Mr Smile Iwejua for his love, support and understanding. To my parents, Elder & Mrs S.C Ekpendu, for always being there for me. And finally to God, for his mercies. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My greatest thanks go to the Almighty God for his steadfast love and for bringing me thus far in my academics. To him be all the glory. My Supervisor, Dr Mike A. Ezugu who patiently taught, read and supervised this research work, your well of blessings will never run dry. My ever smiling husband, Mr Smile Iwejua, your smile and support took me a long way. -

Purple Hibiscus

1 A GLOSSARY OF IGBO WORDS, NAMES AND PHRASES Taken from the text: Purple Hibiscus by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Appendix A: Catholic Terms Appendix B: Pidgin English Compiled & Translated for the NW School by: Eze Anamelechi March 2009 A Abuja: Capital of Nigeria—Federal capital territory modeled after Washington, D.C. (p. 132) “Abumonye n'uwa, onyekambu n'uwa”: “Am I who in the world, who am I in this life?”‖ (p. 276) Adamu: Arabic/Islamic name for Adam, and thus very popular among Muslim Hausas of northern Nigeria. (p. 103) Ade Coker: Ade (ah-DEH) Yoruba male name meaning "crown" or "royal one." Lagosians are known to adopt foreign names (i.e. Coker) Agbogho: short for Agboghobia meaning young lady, maiden (p. 64) Agwonatumbe: "The snake that strikes the tortoise" (i.e. despite the shell/shield)—the name of a masquerade at Aro festival (p. 86) Aja: "sand" or the ritual of "appeasing an oracle" (p. 143) Akamu: Pap made from corn; like English custard made from corn starch; a common and standard accompaniment to Nigerian breakfasts (p. 41) Akara: Bean cake/Pea fritters made from fried ground black-eyed pea paste. A staple Nigerian veggie burger (p. 148) Aku na efe: Aku is flying (p. 218) Aku: Aku are winged termites most common during the rainy season when they swarm; also means "wealth." Akwam ozu: Funeral/grief ritual or send-off ceremonies for the dead. (p. 203) Amaka (f): Short form of female name Chiamaka meaning "God is beautiful" (p. 78) Amaka ka?: "Amaka say?" or guess? (p. -

Igbo Folktales and the Evolution of the Idea of Chukwu As the Supreme God of Igbo Religion Chukwuma Azuonye, University of Massachusetts Boston

University of Massachusetts Boston From the SelectedWorks of Chukwuma Azuonye April, 1987 Igbo Folktales and the Evolution of the Idea of Chukwu as the Supreme God of Igbo Religion Chukwuma Azuonye, University of Massachusetts Boston Available at: https://works.bepress.com/chukwuma_azuonye/70/ ISSN 0794-6961 Nsukka Journal of LJnguistics and African Languages Number 1, April 1987 IGBO FOLKTALES AND THE EVOLUTION OF THE IDEA OF CHUKWU AS THE SUPREME GOD OF IGBO RELIGION Chukwuma AZ\lonye This analysis of Igbo folktales reveals eight distinct phases in the evolution of the idea of Chukwu as the supreme God of Igbo religion. In the first phase, dating back to primeval times, the Igbo recognized several supreme nature deities in various domains. This was followed by a phase of the undisputed supremacy of )Ud (the Earth Goddess) as supreme deity. Traces of that primeval dominance persist till today in some parts of Igboland. The third phase was one of rivalry over supremacy· between Earth and Sky, possibly owing to influences from religious traditions founded on the belief in a supreme sky-dwelling God. In the fourth and fifth phases, the idea of Chukwu as supreme. deity was formally established by the Nri and Ar? respectively in support of their.hegemonic'enterprise in Igbo- land. The exploitativeness of the ArC? powez- seems to .have resulted in the debasement of the idea of Chukwu as supreme God in the Igbo mind, hence the satiric. and.~ images of the anthropo- morphic supreme God in various folktales from the .sixth phase. The sev~nth phase saw the selection, adoption and adaptation of some of the numerous ideas of supreme God founn bv the Christian missionaries in their efforts to propagate Christianity in the idiom of the people.