SCRP Guide Fall 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AND ALGERIAN IVY (Hedera Canariensis) in CALIFORNIA

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UNL | Libraries University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Proceedings of the 6th Vertebrate Pest Vertebrate Pest Conference Proceedings Conference (1974) collection March 1974 THE ASSOCIATION OF THE ROOF RAT (Rattus rattus) WITH THE HIMALAYAN BLACKBERRY (Rubus discolor) AND ALGERIAN IVY (Hedera canariensis) IN CALIFORNIA Val J. Dutson California Health Department, Berkeley, CA Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/vpc6 Part of the Environmental Health and Protection Commons Dutson, Val J., "THE ASSOCIATION OF THE ROOF RAT (Rattus rattus) WITH THE HIMALAYAN BLACKBERRY (Rubus discolor) AND ALGERIAN IVY (Hedera canariensis) IN CALIFORNIA" (1974). Proceedings of the 6th Vertebrate Pest Conference (1974). 10. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/vpc6/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vertebrate Pest Conference Proceedings collection at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the 6th Vertebrate Pest Conference (1974) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE ASSOCIATION OF THE ROOF RAT (Rattus rattus) WITH THE HIMALAYAN BLACKBERRY (Rubus discolor) AND ALGERIAN IVY (Hedera canariensis) IN CALIFORNIA VAL J. DUTSON, Public Health Biologist, Vector Control Section, California Health Department, Berkeley, California ABSTRACT: The roof rat (Rattus rattus) u t i l i z e s Algerian ivy and the Himalayan blackberry for food and cover, often l iving independent of man. Algerian ivy is the most popular ornamental and ground cover plant in California and is used extensively for landscaping, particularly in southern California. -

Conceptual Design Documentation

Appendix A: Conceptual Design Documentation APPENDIX A Conceptual Design Documentation June 2019 A-1 APPENDIX A: CONCEPTUAL DESIGN DOCUMENTATION The environmental analyses in the NEPA and CEQA documents for the proposed improvements at Oceano County Airport (the Airport) are based on conceptual designs prepared to provide a realistic basis for assessing their environmental consequences. 1. Widen runway from 50 to 60 feet 2. Widen Taxiways A, A-1, A-2, A-3, and A-4 from 20 to 25 feet 3. Relocate segmented circle and wind cone 4. Installation of taxiway edge lighting 5. Installation of hold position signage 6. Installation of a new electrical vault and connections 7. Installation of a pollution control facility (wash rack) CIVIL ENGINEERING CALCULATIONS The purpose of this conceptual design effort is to identify the amount of impervious surface, grading (cut and fill) and drainage implications of the projects identified above. The conceptual design calculations detailed in the following figures indicate that Projects 1 and 2, widening the runways and taxiways would increase the total amount of impervious surface on the Airport by 32,016 square feet, or 0.73 acres; a 6.6 percent increase in the Airport’s impervious surface area. Drainage patterns would remain the same as both the runway and taxiways would continue to sheet flow from their centerlines to the edge of pavement and then into open, grassed areas. The existing drainage system is able to accommodate the modest increase in stormwater runoff that would occur, particularly as soil conditions on the Airport are conducive to infiltration. Figure A-1 shows the locations of the seven projects incorporated in the Proposed Action. -

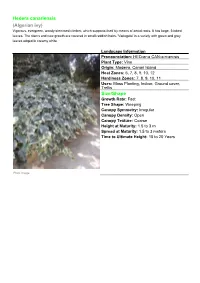

Hedera Canariensis (Algerian Ivy) Vigorous, Evergreen, Woody-Stemmed Climber, Which Supports Itself by Means of Aerial Roots

Hedera canariensis (Algerian ivy) Vigorous, evergreen, woody-stemmed climber, which supports itself by means of aerial roots. It has large, 3-lobed leaves. The stems and new growth are covered in small reddish hairs. 'Variegata' is a variety with green and grey leaves edged in creamy white. Landscape Information Pronounciation: HED-er-a CAN-a-ri-en-sis Plant Type: Vine Origin: Madeira, Canari Island Heat Zones: 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12 Hardiness Zones: 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Uses: Mass Planting, Indoor, Ground cover, Trellis Size/Shape Growth Rate: Fast Tree Shape: Weeping Canopy Symmetry: Irregular Canopy Density: Open Canopy Texture: Coarse Height at Maturity: 1.5 to 3 m Spread at Maturity: 1.5 to 3 meters Time to Ultimate Height: 10 to 20 Years Plant Image Hedera canariensis (Algerian ivy) Botanical Description Foliage Leaf Arrangement: Alternate Leaf Venation: Palmate Leaf Persistance: Evergreen Leaf Type: Simple Leaf Blade: 5 - 10 cm Leaf Shape: Cordate Leaf Margins: Entire Leaf Textures: Leathery Leaf Scent: No Fragance Color(growing season): Green, Variegated Color(changing season): Green Leaf Image Flower Flower Showiness: False Flower Size Range: 3 - 7 Flower Type: Capitulum Flower Sexuality: Monoecious (Bisexual) Flower Scent: No Fragance Flower Color: White Seasons: Fall Trunk Trunk Susceptibility to Breakage: Generally resists breakage Number of Trunks: Multi-Trunked Trunk Esthetic Values: Not Showy Fruit Fruit Type: Berry Fruit Showiness: False Fruit Size Range: 0 - 1.5 Fruit Colors: Blue Seasons: Fall Hedera canariensis (Algerian ivy) -

Tagawa Gardens Algerian

Algerian Ivy Hedera algeriensis Height: 20 feet Spread: 3 feet Sunlight: Hardiness Zone: 7 Other Names: syn. Hedera canariensis var. algeriensis Description: An evergreen climbing vine or dense groundcover with beautiful deep green leaves; salt tolerant leaves may bronze in winter; a very drought tolerant ivy, once established; vigorous grower Ornamental Features Algerian Ivy foliage Photo courtesy of NetPS Plant Finder Algerian Ivy has dark green foliage. The glossy lobed leaves remain dark green throughout the winter. Neither the flowers nor the fruit are ornamentally significant. Landscape Attributes Algerian Ivy is a multi-stemmed evergreen woody vine with a twining and trailing habit of growth. Its average texture blends into the landscape, but can be balanced by one or two finer or coarser trees or shrubs for an effective composition. This woody vine will require occasional maintenance and upkeep, and can be pruned at anytime. Gardeners should be aware of the following characteristic(s) that may warrant special consideration; - Spreading - Invasive Algerian Ivy is recommended for the following landscape applications; - Hedges/Screening - General Garden Use - Groundcover - Container Planting Planting & Growing Algerian Ivy will grow to be about 20 feet tall at maturity, with a spread of 3 feet. As a climbing vine, it tends to be leggy near the base and should be underplanted with low-growing facer plants. It should be planted near a fence, trellis or other landscape structure where it can be trained to grow upwards on it, or allowed to trail off a retaining wall or slope. It grows at a fast rate, and under ideal conditions can be expected to live for approximately 30 years. -

Journal Editorial Staff: Rachel Cobb, David Pfaff, Patricia Riley Hammer, Henri Nier, Suzanne Pierot, Sabina Sulgrove, Russell Windle

Spring 2010 Volume 36 IVY J OURNAL IVY OF THE YEAR 2011 Hedera helix ‘Ivalace’ General Information Press Information American Ivy Society [email protected] P. O. Box 163 Deerfield, NJ 08313 Ivy Identification, Registration Membership Russell A. Windle The American Ivy Society Membership American Ivy Society Laurie Perper P.O. Box 461 512 Waterford Road Lionville, PA 19353-0461 Silver Spring, MD, 20901 [email protected] Officers and Directors President—Suzanne Warner Pierot Treasurer—Susan Hendley Membership—Laurie Perper Registrar, Ivy Research Center Director—Russell Windle Taxonomist—Dr. Sabina Mueller Sulgrove Rosa Capps, Rachel Cobb, Susan Cummings, Barbara Furlong, Patricia Riley Hammer, Constance L. Meck, Dorothy Rouse, Daphne Pfaff, Pearl Wong Ivy Journal Editorial Staff: Rachel Cobb, David Pfaff, Patricia Riley Hammer, Henri Nier, Suzanne Pierot, Sabina Sulgrove, Russell Windle The Ivy Journal is published once per year by the American Ivy Society, a nonprofit educational organization. Membership includes a new ivy plant each year, subscription to the Ivy Journal and Between the Vines, the newsletter of The American Ivy Society. Editorial submissions are welcome. Mail typed, double-spaced manuscript to the Ivy Journal Editor, The American Ivy Society. Enclose a self-addressed, stamped envelope if you wish manuscript and/ or artwork to be returned. Manuscripts will be handled with reasonable care. However, AIS assumes no responsibility for safety of artwork, photographs, or manuscripts. Every precaution is taken to ensure accuracy but AIS cannot accept responsibility for the corrections or accuracy of the information supplied herein or for any opinion expressed. The American Ivy Society P. O. Box 163, Deerfield Street, NJ 08313 www.ivy.org Remember to send AIS your new address. -

Annals of the History and Philosophy of Biology

he name DGGTB (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Geschichte und Deutsche Gesellschaft für Theorie der Biologie; German Society for the History and Philosophy of BioT logy) refl ects recent history as well as German tradition. Geschichte und Theorie der Biologie The Society is a relatively late addition to a series of German societies of science and medicine that began with the “Deutsche Gesellschaft für Geschichte der Medizin und der Naturwissenschaften”, Annals of the History founded in 1910 by Leipzig University‘s Karl Sudhoff (1853-1938), who wrote: “We want to establish a ‘German’ society in order to gather Ger- and Philosophy of Biology man-speaking historians together in our special disciplines so that they form the core of an international society…”. Yet Sudhoff, at this Volume 17 (2012) time of burgeoning academic internationalism, was “quite willing” to accommodate the wishes of a number of founding members and formerly Jahrbuch für “drop the word German in the title of the Society and have it merge Geschichte und Theorie der Biologie with an international society”. The founding and naming of the Society at that time derived from a specifi c set of histori- cal circumstances, and the same was true some 80 years lat- er when in 1991, in the wake of German reunifi cation, the “Deutsche Gesellschaft für Geschichte und Theorie der Biologie” was founded. From the start, the Society has been committed to bringing stud- ies in the history and philosophy of biology to a wide audience, us- ing for this purpose its Jahrbuch für Geschichte und Theorie der Biologie. Parallel to the Jahrbuch, the Verhandlungen zur Geschichte und Theorie der Biologie has become the by now traditional medi- Annals of the History and Philosophy Biology, Vol. -

Vascular Plants of Santa Cruz County, California

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST of the VASCULAR PLANTS of SANTA CRUZ COUNTY, CALIFORNIA SECOND EDITION Dylan Neubauer Artwork by Tim Hyland & Maps by Ben Pease CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY, SANTA CRUZ COUNTY CHAPTER Copyright © 2013 by Dylan Neubauer All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without written permission from the author. Design & Production by Dylan Neubauer Artwork by Tim Hyland Maps by Ben Pease, Pease Press Cartography (peasepress.com) Cover photos (Eschscholzia californica & Big Willow Gulch, Swanton) by Dylan Neubauer California Native Plant Society Santa Cruz County Chapter P.O. Box 1622 Santa Cruz, CA 95061 To order, please go to www.cruzcps.org For other correspondence, write to Dylan Neubauer [email protected] ISBN: 978-0-615-85493-9 Printed on recycled paper by Community Printers, Santa Cruz, CA For Tim Forsell, who appreciates the tiny ones ... Nobody sees a flower, really— it is so small— we haven’t time, and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time. —GEORGIA O’KEEFFE CONTENTS ~ u Acknowledgments / 1 u Santa Cruz County Map / 2–3 u Introduction / 4 u Checklist Conventions / 8 u Floristic Regions Map / 12 u Checklist Format, Checklist Symbols, & Region Codes / 13 u Checklist Lycophytes / 14 Ferns / 14 Gymnosperms / 15 Nymphaeales / 16 Magnoliids / 16 Ceratophyllales / 16 Eudicots / 16 Monocots / 61 u Appendices 1. Listed Taxa / 76 2. Endemic Taxa / 78 3. Taxa Extirpated in County / 79 4. Taxa Not Currently Recognized / 80 5. Undescribed Taxa / 82 6. Most Invasive Non-native Taxa / 83 7. Rejected Taxa / 84 8. Notes / 86 u References / 152 u Index to Families & Genera / 154 u Floristic Regions Map with USGS Quad Overlay / 166 “True science teaches, above all, to doubt and be ignorant.” —MIGUEL DE UNAMUNO 1 ~ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ~ ANY THANKS TO THE GENEROUS DONORS without whom this publication would not M have been possible—and to the numerous individuals, organizations, insti- tutions, and agencies that so willingly gave of their time and expertise. -

English Ivy (Hedera Helix)

W231 English Ivy (Hedera helix) Becky Koepke-Hill, Extension Assistant, Plant Sciences Greg Armel, Assistant Professor, Extension Weed Specialist for Invasive Weeds, Plant Sciences Origin: English ivy is native to Europe, from northeastern Ireland to southern Scandinavia, and south to Spain. It is also native in western Asia and northern Africa. English ivy arrived in North America as a landscape plant and escaped from those landscape settings into natural areas. Description: This evergreen perennial vine can grow up to 90 feet with proper support. English ivy has two forms: juvenile and mature. Juvenile plants have leaves with three to five lobes and herbaceous stems or very thin woody stems. Mature plants have leaves with no lobes and thick woody stems, with a primary support- ing stem containing hairs similar to poison ivy. The supporting stem grows up trees or walls. Most English ivy plants in landscapes are juvenile plants. Both mature and juvenile plants have leaves with smooth edges, which are dark green with white or pale green veins. Small, inconspicuous flowers appear in the fall on mature stems and produce dark blue to black fruits. Habitat: English ivy grows in fields, hedgerows, woodlands, forest edges and upland areas. It does not thrive in wet or extremely moist areas, but will grow in a wide range of soil pH. New populations generally occur on land that has been disturbed by humans or natural occurrences. Environmental Impact: English ivy grows into thick carpets on forest floors, crowding out native vegetation, and it is one of few exotic plants that can thrive in full, deep shade. -

Diseases of Floriculture Crops in South Carolina

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2009 Diseases of Floriculture Crops in South Carolina: Evaluation of a Pre-plant Sanitation Treatment and Identification of Species of Phytophthora Ernesto Robayo Camacho Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Plant Pathology Commons Recommended Citation Robayo Camacho, Ernesto, "Diseases of Floriculture Crops in South Carolina: Evaluation of a Pre-plant Sanitation Treatment and Identification of Species of Phytophthora" (2009). All Theses. 663. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/663 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DISEASES OF FLORICULTURE CROPS IN SOUTH CAROLINA: EVALUATION OF A PRE‐PLANT SANITATION TREATMENT AND IDENTIFICATION OF SPECIES OF PHYTOPHTHORA A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Plant and Environmental Sciences by Ernesto Robayo Camacho August 2009 Accepted by: Steven N. Jeffers, Committee Chair Julia L. Kerrigan William C. Bridges, Jr. ABSTRACT This project was composed of two separate studies. In one study, the species of Phytophthora that have been found associated with diseased floriculture crops in South Carolina and four other states were characterized and identified using molecular (RFLP fingerprints and DNA sequences for ITS regions and cox I and II genes), morphological (sporangia, oogonia, antheridia, oospores, and chlamydospores), and physiological (mating behavior and cardinal temperatures) characters. -

Wildland Urban Interface Approved Plant List

WILDLAND URBAN INTERFACE APPROVED PLANT LIST This approved plant list has been developed to serve as a tool to determine the placement of vegetation within the Wildland Urban Interface areas. The approved plant list has been compiled from several similar lists which pertain to the San Francisco Bay Area and to the State of California. This approved plant list is not intended to be used outside of the San Mateo County area. The “required distance” for each plant is how far the given plant is required to be from a structure. If a plant within the approved plant list is not provided with a “required distance”, the plant has been designated as a fire-resistant plant and may be placed anywhere within the defensible space area. The designation as a fire-resistant plant does not exempt the plant from other Municipal Codes. For example, as per Hillsborough Municipal Code, all trees crowns, including those that have been designated as fire resistant, are required to be 10 feet in distance from any structure. Fire resistant plants have specific qualities that help slow down the spread of fire, they include but are not limited to: • Leaves tend to be supple, moist and easily crushed • Trees tend to be clean, not bushy, and have little deadwood • Shrubs are low-growing (2’) with minimal dead material • Taller shrubs are clean, not bushy or twiggy • Sap is water-like and typically does not have a strong odor • Most fire-resistant trees are broad leafed deciduous (lose their leaves), but some thick-leaf evergreens are also fire resistant. -

County of Riverside Friendly Plant List

ATTACHMENT A COUNTY OF RIVERSIDE CALIFORNIA FRIENDLY PLANT LIST PLANT LIST KEY WUCOLS III (Water Use Classification of Landscape Species) WUCOLS Region Sunset Zones 1 2,3,14,15,16,17 2 8,9 3 22,23,24 4 18,19,20,21 511 613 WUCOLS III Water Usage/ Average Plant Factor Key H-High (0.8) M-Medium (0.5) L-Low (.2) VL-Very Low (0.1) * Water use for this plant material was not listed in WUCOLS III, but assumed in comparison to plants of similar species ** Zones for this plant material were not listed in Sunset, but assumed in comparison to plants of similar species *** Zones based on USDA zones ‡ The California Friendly Plant List is provided to serve as a general guide for plant material. Riverside County has multiple Sunset Zones as well as microclimates within those zones which can affect plant viability and mature size. As such, plants and use categories listed herein are not exhaustive, nor do they constitute automatic approval; all proposed plant material is subject to review by the County. In some cases where a broad genus or species is called out within the list, there may be multiple species or cultivars that may (or may not) be appropriate. The specific water needs and sizes of cultivars should be verified by the designer. Site specific conditions should be taken into consideration in determining appropriate plant material. This includes, but is not limited to, verifying soil conditions affecting erosion, site specific and Fire Department requirements or restrictions affecting plans for fuel modifications zones, and site specific conditions near MSHCP areas. -

Hedera Helix L.; English Ivy Hedera Canariensis Willd.; Algerian Ivy (= H

A WEED REPORT from the book Weed Control in Natural Areas in the Western United States This WEED REPORT does not constitute a formal recommendation. When using herbicides always read the label, and when in doubt consult your farm advisor or county agent. This WEED REPORT is an excerpt from the book Weed Control in Natural Areas in the Western United States and is available wholesale through the UC Weed Research & Information Center (wric.ucdavis.edu) or retail through the Western Society of Weed Science (wsweedscience.org) or the California Invasive Species Council (cal-ipc.org). Hedera helix L.; English ivy Hedera canariensis Willd.; Algerian ivy (= H. helix L. ssp. canariensis (Willd.) Cout.) Hedera hibernica (G. Kirchn.) Bean; Irish or Atlantic ivy English, Algerian and Atlantic ivy Family: Araliaceae Range: Many western states, including Washington, Oregon, California, Idaho, Arizona, and Utah. Habitat: Riparian corridors, moist woodlands, forest margins, coastal habitats, and disturbed sites such as cleared forests, urban waste places, and old homesteads. Requires some moisture year-round. Tolerates deep shade, but thrives where plants receive some summer shade and direct winter sun. Origin: Native to Europe and introduced to the United States as an ornamental. English ivy is still a common landscape ornamental of which there are numerous cultivars. Impacts: Under favorable conditions, plants spread invasively and can develop a dense cover that outcompetes other vegetation in natural areas. Infestations around old homesteads have been present for many years and serve as nursery sites for further spread. It has escaped from cultivation in many places, especially near the coast and along riparian corridors.