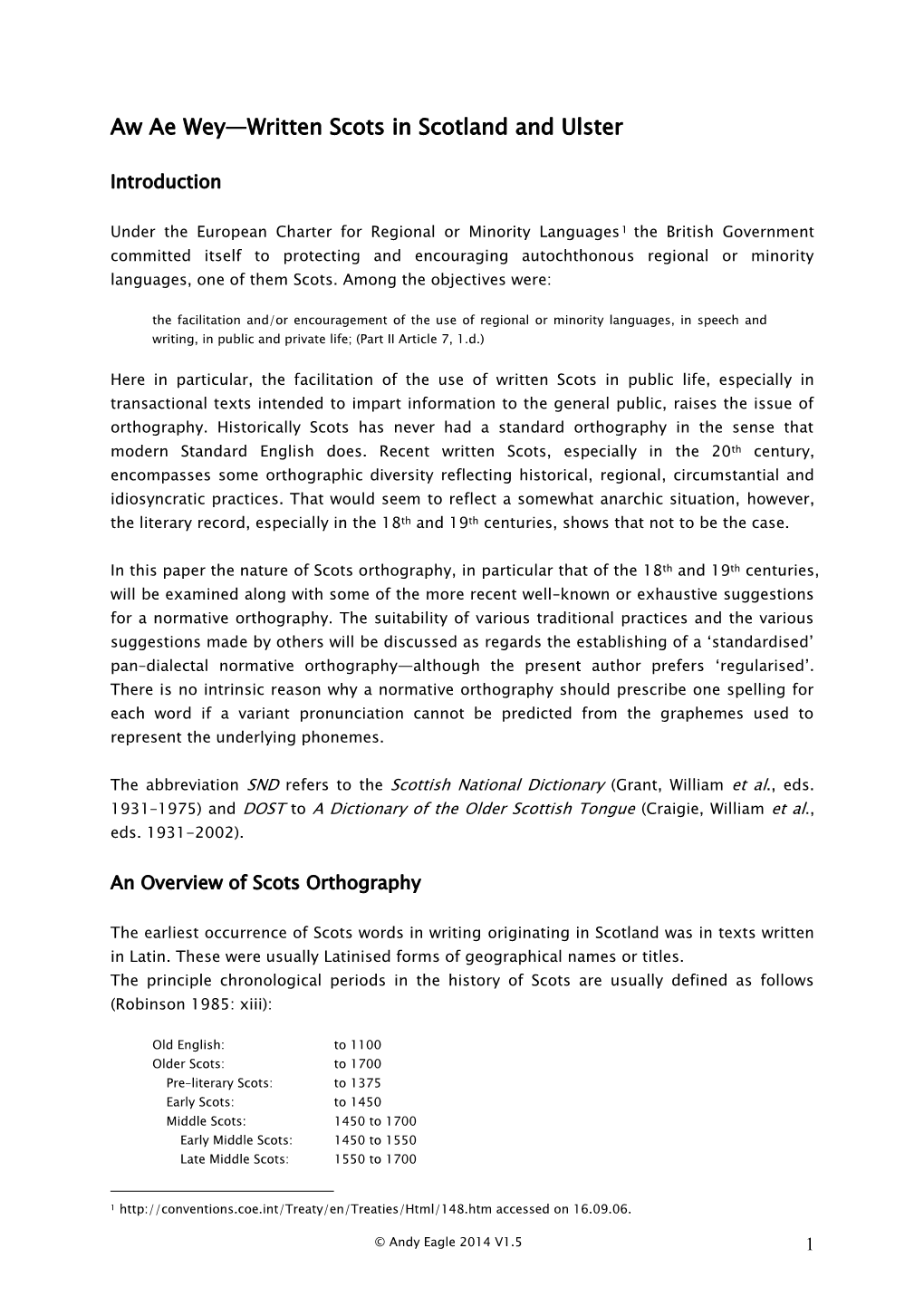

Aw Ae Wey—Written Scots in Scotland and Ulster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Home-Ly Kailyard Nation: Nineteenth-Century Narratives of the Highland and the Myth of Merrie Auld Scotland Author(S): Richard Cook Source: ELH, Vol

The Home-Ly Kailyard Nation: Nineteenth-Century Narratives of the Highland and the Myth of Merrie Auld Scotland Author(s): Richard Cook Source: ELH, Vol. 66, No. 4, The Nineteenth Century (Winter, 1999), pp. 1053-1073 Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30032108 . Accessed: 27/05/2013 15:30 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to ELH. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 143.107.8.10 on Mon, 27 May 2013 15:30:09 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions THE HOME-LY KAILYARD NATION: NINETEENTH- CENTURY NARRATIVES OF THE HIGHLAND AND THE MYTH OF MERRIE AULD SCOTLAND BY RICHARD COOK In his broad survey, Modern Scottish Literature, Alan Bold warns against quick dismissals of the popular late nineteenth-century "Kailyard School" of fiction: "we should be wary of categorizing the kailyarders as sentimental fools; they were men who had a shrewd judgment for public taste and the public responded by adoring the intellectually undemand- ing entertainment the kailyarders produced." Bold's evaluation of the Kailyard (literally, cabbage patch) and its unavoidable presence in Scottish literary and cultural history illustrate the tension between "public taste" and high art, "entertainment" and serious intellect, that still gathers around these national tales. -

AJ Aitken a History of Scots

A. J. Aitken A history of Scots (1985)1 Edited by Caroline Macafee Editor’s Introduction In his ‘Sources of the vocabulary of Older Scots’ (1954: n. 7; 2015), AJA had remarked on the distribution of Scandinavian loanwords in Scots, and deduced from this that the language had been influenced by population movements from the North of England. In his ‘History of Scots’ for the introduction to The Concise Scots Dictionary, he follows the historian Geoffrey Barrow (1980) in seeing Scots as descended primarily from the Anglo-Danish of the North of England, with only a marginal role for the Old English introduced earlier into the South-East of Scotland. AJA concludes with some suggestions for further reading: this section has been omitted, as it is now, naturally, out of date. For a much fuller and more detailed history up to 1700, incorporating much of AJA’s own work on the Older Scots period, the reader is referred to Macafee and †Aitken (2002). Two textual anthologies also offer historical treatments of the language: Görlach (2002) and, for Older Scots, Smith (2012). Corbett et al. eds. (2003) gives an accessible overview of the language, and a more detailed linguistic treatment can be found in Jones ed. (1997). How to cite this paper (adapt to the desired style): Aitken, A. J. (1985, 2015) ‘A history of Scots’, in †A. J. Aitken, ed. Caroline Macafee, ‘Collected Writings on the Scots Language’ (2015), [online] Scots Language Centre http://medio.scotslanguage.com/library/document/aitken/A_history_of_Scots_(1985) (accessed DATE). Originally published in the Introduction, The Concise Scots Dictionary, ed.-in-chief Mairi Robinson (Aberdeen University Press, 1985, now published Edinburgh University Press), ix-xvi. -

6Landscapes of Eden and Hell in the Modem Scottish Novel’

UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW DEPARTMENT OF SCOTTISH LITERATURE A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosonhv 6Landscapes of Eden and Hell in the Modem Scottish Novel’ LEAH N. RANKIN JUNE 2002 SUPERVISED BY DR GERARD CARRUTHERS ProQuest Number: 13818809 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818809 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 \1S&1 g o p H \ Landscapes of Eden and Hell in the Modern Scottish Novel CONTENTS Abstract i Acknowledgements ii 1 Introduction: ‘Landscapes of Eden and Hell: The Kailyard and the Real Scotland’ 1 -2 4 2 George Douglas Brown: ‘From Idylls to Nightmares: Uprooting the Kailyard’ 25 - 45 3 Catherine Carswell: ‘Closed Doors and Caged Birds: False Edens in Scotland and Beyond’ 46 - 69 4 Willa Muir: ‘Hell-fire and Water: Examining the Elements of Calderwick’ 70 - 95 5 J.M. Barrie: ‘The Purgatory of Scotland: A Final Farewell to the Kailyard’ 96 - 123 6 Robin Jenkins: ‘The Regeneration of Good and Evil: The Garden of Eden Stripped Bare’ 124 - 142 Conclusion 143 - 146 Bibliography 147 - 155 Landscapes of Eden and Hell in the Modern Scottish Novel ABSTRACT The following thesis examines the portrayal in a number of modem Scottish novels of Edenic and hellish landscapes, these depictions being primarily connected with the effect of Calvinism on the Scottish mentality. -

The Sigma Tau Delta Review

The Sigma Tau Delta Review Journal of Critical Writing Sigma Tau Delta International English Honor Society Volume 11, 2014 Editor of Publications: Karlyn Crowley Associate Editors: Rachel Gintner Kacie Grossmeier Anna Miller Production Editor: Rachel Gintner St. Norbert College De Pere, Wisconsin Honor Members of Sigma Tau Delta Chris Abani Katja Esson Erin McGraw Kim Addonizio Mari Evans Marion Montgomery Edward Albee Anne Fadiman Kyoko Mori Julia Alvarez Philip José Farmer Scott Morris Rudolfo A. Anaya Robert Flynn Azar Nafisi Saul Bellow Shelby Foote Howard Nemerov John Berendt H.E. Francis Naomi Shihab Nye Robert Bly Alexandra Fuller Sharon Olds Vance Bourjaily Neil Gaiman Walter J. Ong, S.J. Cleanth Brooks Charles Ghigna Suzan-Lori Parks Gwendolyn Brooks Nikki Giovanni Laurence Perrine Lorene Cary Donald Hall Michael Perry Judith Ortiz Cofer Robert Hass David Rakoff Henri Cole Frank Herbert Henry Regnery Billy Collins Peter Hessler Richard Rodriguez Pat Conroy Andrew Hudgins Kay Ryan Bernard Cooper William Bradford Huie Mark Salzman Judith Crist E. Nelson James Sir Stephen Spender Jim Daniels X.J. Kennedy William Stafford James Dickey Jamaica Kincaid Lucien Stryk Mark Doty Ted Kooser Amy Tan Ellen Douglas Ursula K. Le Guin Sarah Vowell Richard Eberhart Li-Young Lee Eudora Welty Timothy Egan Valerie Martin Jessamyn West Dave Eggers David McCullough Jacqueline Woodson Delta Award Recipients Richard Cloyed Elizabeth Holtze Elva Bell McLin Sue Yost Beth DeMeo Elaine Hughes Isabel Sparks Bob Halli E. Nelson James Kevin Stemmler Copyright © 2014 by Sigma Tau Delta All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Sigma Tau Delta, Inc., the International English Honor Society, William C. -

Page 1 Openlearnworks Unit 4: Dialect Diversity Bbyy Bbruuccee

OpenLearn Works Unit 4: Dialect diversity by Bruce Eunson Copyright © 2018 The Open University 2 of 23 http://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/course/view.php?id=2705 Tuesday 7 January 2020 Contents Introduction 4 4. Introductory handsel 4 4.1 The Scots dialect of the Shetland Isles 7 4.2 Dialects of Scots in today’s Scotland 9 4.3 A brief history of the Shetland dialect 12 4.4 Dialect diversity and bilingualism 15 4.5 The 2011 Census 19 Further research 22 References 23 Acknowledgements 23 3 of 23 http://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/course/view.php?id=2705 Tuesday 7 January 2020 Introduction Introduction In this unit you will learn about dialect diversity within Scots language. Like many languages, Scots is spoken and written in a variety of regional dialects. This unit will introduce you to these dialects and discuss some of the differences that appear between them. The predominance, and history of, the dialects of Scots language are particularly important when studying and understanding Scots due to the fact that the language is presently without an acknowledged written standard. Whilst there are differences between the regional dialects, they are also tied together by common features and similarities. Important details to take notes on throughout this unit: ● The number of Scots language dialects commonly recognised as being used in Scotland today ● The present state of Scots language ● The regard which regional speakers of Scots have for “their” dialect ● The influence of Norn (a North Germanic language belonging to the same group as Norwegian) on Scots language and the different dialects today ● The census of Scotland in March 2011, which asked for the first time in its history whether people could speak, read, write or understand Scots. -

“…If We Care to Preserve Even That” Scots and the Question of Language Revitalization

“…if we care to preserve even that” Scots and the question of Language Revitalization Lindsay Voigt Ling 100 – Senior Thesis December 6, 2002 I surveyed the scene: a sea of white hair and grandmotherly attire greeted me as I entered the hall. On Sundays, this was the room where I attended church. Tonight, though, a stage was set up and sixteen kilted fiddlers were tuning their instruments as the rows of old friends in the audience chatted. Not only was I the youngest person there by at least forty years, I was also the only American, so any hopes I had had of blending into the crowd were effectively squelched. A kindly “gran” pointed to an empty chair next to her and I settled in for a few hours of Scottish culture. One of the fiddlers had been elected emcee for the evening, a lady from Inverurie, not too far from Aberdeen, where the concert was being held. She stood and welcomed us all – that much I got – but for the rest of the evening my ears strained and my mind worked overtime to make sense of what this nice woman was saying. My fellow audience members hadn’t the slightest difficulty: some parts of her commentary had them nodding solemnly in agreement, others had them chortling with glee, all while I stared blankly and tried not to stick out more than I already did. “I speak English, right? And they speak English, right? Then why on earth do I not have a clue what she’s saying?!?” is about how my mental process was going at the moment. -

'Like Pushkin, I': Hugh Macdiarmid and Russia Patrick Crotty University of Aberdeen

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 44 Article 7 Issue 1 Scottish-Russian Literary Relations Since 1900 12-1-2018 'Like Pushkin, I': Hugh MacDiarmid and Russia Patrick Crotty University of Aberdeen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Russian Literature Commons Recommended Citation Crotty, Patrick (2019) "'Like Pushkin, I': Hugh MacDiarmid and Russia," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 44: Iss. 1, 47–89. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol44/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “LIKE PUSHKIN, I”: HUGH MACDIARMID AND RUSSIA Patrick Crotty . I’m a poet (And you c’ud mak allowances for that!) “Second Hymn to Lenin” (1932)1 Hugh MacDiarmid has never enjoyed the canonical status his acolytes consider his due. Those acolytes have dwindled in number since the 1970s and ’80s, and, as the end of the second decade of the twenty-first century approaches, there is scant evidence of live interest in the poet’s achievement anywhere in the world, least of all his native Scotland. One reason for this is that MacDiarmid, as Seamus Heaney ruefully remarked, “gave his detractors plenty to work with”;2 quite apart from indulging in cultural and political opining sufficiently provocative for the public at large to dismiss him as a crank, he published a dismaying amount of slipshod and even banal verse, mainly in his later years. -

National Qualifications Curriculum Support

NATIONAL QUALIFICATIONS CURRICULUM SUPPORT English and Communication Using Scottish Texts Support Notes and Bibliographies [MULTI-LEVEL] Edited by David Menzies INTRODUCTION First published 1999 Electronic version 2001 © Scottish Consultative Council on the Curriculum 1999 This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part for educational purposes by educational establishments in Scotland provided that no profit accrues at any stage. Acknowledgement Learning and Teaching Scotland gratefully acknowledge this contribution to the Higher Still support programme for English. The help of Gordon Liddell is acknowledged in the early stages of this project. Permission to quote the following texts is acknowledged with thanks: ‘Burns Supper’ by Jackie Kay, from Two’s Company (Blackie, 1992), is reproduced by permission of Penguin Books Ltd; ‘War Grave’ by Mary Stewart, from Frost on the Window (Hodder, 1990), is reproduced by permission of Hodder & Stoughton Ltd; ‘Stealing’, from Selling Manhattan by Carol Ann Duffy, published by Anvil Press Poetry in 1987; ‘Ophelia’, from Ophelia and Other Poems by Elizabeth Burns, published by Polygon in 1991. ISBN 1 85955 823 2 Learning and Teaching Scotland Gardyne Road Dundee DD5 1NY www.LTScotland.com HISTORY 3 CONTENTS Section 1: Introduction (David Menzies) 1 Section 2: General works and background reading (David Menzies) 4 Section 3: Dramatic works (David Menzies) 7 Section 4: Prose fiction (Beth Dickson) 30 Section 5: Non-fictional prose (Andrew Noble) 59 Section 6: Poetry (Anne Gifford) 64 Section 7: Media texts (Margaret Hubbard) 85 Section 8: Gaelic texts in translation (Donald John MacLeod) 94 Section 9: Scots language texts (Liz Niven) 102 Section 10: Support for teachers (David Menzies) 122 ENGLISH III INTRODUCTION HISTORY 5 INTRODUCTION SECTION 1 Introduction One of the significant features of the provision for English in the Higher Still Arrangements is the prominence given to the study of Scottish language and literature. -

A. J. Aitken James Murray, Master of Scots (1996)1

A. J. Aitken James Murray, Master of Scots (1996)1 Edited by Caroline Macafee, 2015 How to cite this paper (adapt to the desired style): Aitken, A. J. (1996, 2015) ‘James Murray, Master of Scots’, in †A. J. Aitken, ed. Caroline Macafee, ‘Collected Writings on the Scots Language’ (2015), [online] Scots Language Centre http://medio.scotslanguage.com/library/document/aitken/James_Murray,_master_of_Scots_(1996) (accessed DATE). Originally published Review of Scottish Culture 9 (1996), 14–34. [14] James Murray is best known as the first and principal editor of the Oxford English Dictionary. He has been described by a distinguished lexicographer of today as “a lexicographer greater by far than Dr Johnson and greater perhaps than any lexicographer of his own time or since in Britain, the United States or Europe” (Burchfield, 1977). He is also the founder of the modern study of Scots, both historical and descriptive. In this respect, an American scholar investigating a phenomenon of Appalachian dialect which probably originated in Scots, recently said of him, “All paths lead back to Murray.”2 The same could be said of many other phenomena of Scots speech which we might like to study. Life Murray was born in 1837 in Denholm, Roxburghshire, near Hawick. Both of his parents were local people and staunch members of the local Congregational Church. From them Murray got his strong religious convictions and his almost fanatical sense of duty, probity and perfectionism. 1 [1] A slightly revised and expanded version of the first annual Scotch Malt Whisky Society lecture on Scots language, delivered in the Society’s premises, The Vaults, 87 Giles Street, Leith, on 3 March, 1992. -

Pentland Place-Names: an Introductory Guide

Pentland Place-Names: An introductory guide John Baldwin and Peter Drummond TECTIN PRO G & G, E IN N V H R A E N S C I N N O G C Green Hairstreak butterfly on Blaeberry painted by Frances Morgan, Member of Friends of the Pentlands F R S I D EN N DS LA of the PENT Published by: The Friends of the Pentlands, Edinburgh, Scotland www.pentlandfriends.plus.com Registered Scottish Charity, No: SC035514 First published 2011 Copyright © Individual contributors (text) and Friends of the Pentlands (format/map) 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced stored in or introduced into a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, digital, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher and copyright holders. Acknowledgements: The Friends of the Pentlands (FoP) would like to acknowledge the work of John Baldwin (University of Edinburgh) and Peter Drummond (University of Glasgow) in compiling this booklet. Without them, the project would never have happened. The authors are particularly grateful to Simon Taylor (University of Glasgow) for many helpful comments. Remaining errors, over-simplifications or over-generous speculations are theirs alone! The Friends of the Pentlands much appreciate the cartographic skills of David Longworth and wish to acknowledge the financial support of Scottish Natural Heritage and South Lanarkshire Council. Cover Photograph: View of the Howe, Loganlee Reservoir and Castlelaw by Victor Partridge. Designed and printed -

AJ Aitken the Pronunciation Entries for The

A. J. Aitken The pronunciation entries for the CSD (1985)1 Edited by Caroline Macafee, 2015 How to cite this paper (adapt to the desired style): Aitken, A. J. (1985, 2015) ‘The pronunciation entries for the CSD’ in †A. J. Aitken, ed. Caroline Macafee, ‘Collected Writings on the Scots Language’ (2015), [online] Scots Language Centre http://medio.scotslanguage.com/library/document/aitken/The_pronunciation_entries_for_the_CSD_(1985) (accessed DATE). Originally published Dictionaries 7 (1985) 134–150. [134] In the Concise Scots Dictionary (CSD) we have given by phonetic transcription a representative set of pronunciations for every entry in the dictionary, with the following exceptions. The exceptions, entries not accompanied by a phonetic transcription, are: 1. Those whose spelling and pronunciation agree with the same word in Standard English, e.g. certificate, or gallon in Table 1. 2. Entries whose spellings, according to the ordinary rules of general English orthography, appear unambiguously to imply their pronunciations (with the additional assumption that if there is no statement or implication by normal rule of English stress- position, stress is on the initial syllable): e.g. cantrip, and gallyie in Table 1. Apart from these, which, so to speak, do not need a transcription, there is another, smaller, set which strictly does, but is also left untranscribed. These are a very few words of limited currency – uncommon or ephemeral – nearly all obsolete, whose pronunciation seems likely to be difficult or impossible to ascertain. So if there is no transcription, this means either that the reader is expected to apply his knowledge of ordinary English to the spellings or that his guess is as good as mine. -

A Preliminary Approach to Linguistic Itemisation and Repertoire of Scots in 19Th

Tissens !1 ! FACULTAD DE FILOLOGÍA UNIVERSIDAD DE SALAMANCA FACULTAD DE FILOLOGÍA GRADO EN ESTUDIOS INGLESES Trabajo de Fin de Grado THE THISTLE ENREGISTERED A Preliminary Approach to Linguistic Itemisation and Repertoire of Scots in 19th- Century British Literature René Pérez Tissens Fco. Javier Ruano García Salamanca, 2018 Tissens !2 ! FACULTAD DE FILOLOGÍA UNIVERSIDAD DE SALAMANCA FACULTAD DE FILOLOGÍA GRADO EN ESTUDIOS INGLESES Trabajo de Fin de Grado THE THISTLE ENREGISTERED A Preliminary Approach to Linguistic Itemisation and Repertoire of Scots in 19th- Century British Literature This thesis is submitted for the degree of English Studies Date: July, 2018 Tutor: Fco. Javier Ruano García Vº Bº Signature Tissens !3 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction…………………………………………………………………6 II. Enregisterment: Non-standard English and Scotland | Oral-transcribed Discourse, Production of Energy, Grammatical Repertoire — Sociological Conceptualisation of Scots…………………………………………………7 III. History and Scots: a Proemial Memoir on Marginalisation………………10 IV. Varieties of Scots in Literature: Coincidences and Divergences — Linguistic-branding in Dialogue and the Creation of Pathos:…………….12 A. Lallans Represented: “Gaen Doon the Brae”………………………….13 1. J. M. Barrie’s A Window in Thrums (1889): a) Lexical items (1) noted Scots terminology b) Phonetic design (1) the descried pattern c) Idiomatic particles (1) Barrie’s reminiscent stock B. Highland Ruminations: Rural Perthshire virtualised…………………..17 1. Ian Maclaren’s Beside the Bonnie Brier Bush (1894): a) Lexical items (1) noted concurrences b) Phonetic design (1) parallelisms and deviations c) Idiomatic particles C. From Similarities to the Construction of Methodic Scots-dialogue Writing…………………………………………………………………20 V. Conclusion: Linguistic Scottishness — an Evolutive Continuum Settled..21 Tissens !4 ABSTRACT Standardisation of linguistic varieties implies a making of choices.