Prokofiev O D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Musical Partnership of Sergei Prokofiev And

THE MUSICAL PARTNERSHIP OF SERGEI PROKOFIEV AND MSTISLAV ROSTROPOVICH A CREATIVE PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF MUSIC IN PERFORMANCE BY JIHYE KIM DR. PETER OPIE - ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2011 Among twentieth-century composers, Sergei Prokofiev is widely considered to be one of the most popular and important figures. He wrote in a variety of genres, including opera, ballet, symphonies, concertos, solo piano, and chamber music. In his cello works, of which three are the most important, his partnership with the great Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich was crucial. To understand their partnership, it is necessary to know their background information, including biographies, and to understand the political environment in which they lived. Sergei Prokofiev was born in Sontovka, (Ukraine) on April 23, 1891, and grew up in comfortable conditions. His father organized his general education in the natural sciences, and his mother gave him his early education in the arts. When he was four years old, his mother provided his first piano lessons and he began composition study as well. He studied theory, composition, instrumentation, and piano with Reinhold Glière, who was also a composer and pianist. Glière asked Prokofiev to compose short pieces made into the structure of a series.1 According to Glière’s suggestion, Prokofiev wrote a lot of short piano pieces, including five series each of 12 pieces (1902-1906). He also composed a symphony in G major for Glière. When he was twelve years old, he met Glazunov, who was a professor at the St. -

Read Book Sergei Prokofiev Peter and Wolf Pdf Free Download

SERGEI PROKOFIEV PETER AND WOLF PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Sergei Prokofiev | 40 pages | 14 Sep 2004 | Random House USA Inc | 9780375824302 | English | New York, United States Sergei Prokofiev Peter and Wolf PDF Book Prokofiev had been considering making an opera out of Leo Tolstoy 's epic novel War and Peace , when news of the German invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June made the subject seem all the more timely. This article contains a list of works that does not follow the Manual of Style for lists of works often, though not always, due to being in reverse-chronological order and may need cleanup. William F. You have entered an incorrect email address! The cat quickly climbs into the tree with the bird, but the duck, who has jumped out of the pond, is chased, overtaken, and swallowed by the wolf. Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. To this day, elementary school children hear Peter and the Wolf during school assemblies or at concerts for young people. Merriam-Webster Dictionary. The Independent. However, Prokofiev was dissatisfied with the rhyming text produced by Antonina Sakonskaya, a then popular children's author. The Lives of Ingolf Dahl. Russian composer — Explore more from this episode More. Each character of this tale is represented by a corresponding instrument in the orchestra: the bird by a flute, the duck by an oboe, the cat by a clarinet playing staccato in a low register, the grandfather by a bassoon, the wolf by three horns, Peter by the string quartet, the shooting of the hunters by the kettle drums and bass drum. -

Istanbul Technical University Institute of Social Sciences Aesthetical and Technical Analysis of Selected Flute Works by S

ISTANBUL TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY ★ INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AESTHETICAL AND TECHNICAL ANALYSIS OF SELECTED FLUTE WORKS BY SOFIA GUBAIDULINA Ph.D. THESIS Zehra Ezgi KARA Department of Music Music Programme MARCH 2019 ISTANBUL TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY ★ INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AESTHETICAL AND TECHNICAL ANALYSIS OF SELECTED FLUTE WORKS BY SOFIA GUBAIDULINA Ph.D. THESIS Zehra Ezgi KARA (409112005) Department of Music Music Programme Thesis Advisor: Assoc. Prof. Jülide GÜNDÜZ MARCH 2019 İSTANBUL TEKNİK ÜNİVERSİTESİ ★ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ SOFIA GUBAIDULINA’NIN SEÇİLİ FLÜT ESERLERİNİN ESTETİK VE TEKNİK ANALİZİ DOKTORA TEZİ Zehra Ezgi KARA (409112005) Müzik Anabilim Dalı Müzik Programı Tez Danışmanı: Doç. Jülide GÜNDÜZ MART 2019 Zehra Ezgi Kara, a Ph.D. student of ITU Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences student ID 409112005, successfully defended the thesis/dissertation entitled “AESTHETICAL AND TECHNICAL ANALYSIS OF SELECTED FLUTE WORKS BY SOFIA GUBAIDULINA”, which she prepared after fulfilling the requirements specified in the associated legislations, before the jury whose signatures are below. Thesis Advisor: Assoc. Prof. Jülide Gündüz …………… Istanbul Technical University Jury Members: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Yelda Özgen Öztürk .…………… Istanbul Technical University Assoc. Prof. Dr. Jerfi Aji .…………… Istanbul Technical University Prof. Dr. Gülden Teztel .…………… Istanbul University Assoc. Prof. Dr. Müge Hendekli .…………… Istanbul University Date of Submission : 05 February 2019 Date of Defense : 20 March 2019 v vi To Mom, Dad and my dog, Justin. vii viii FOREWORD This thesis, entitled “Aesthetical and Technical Analysis of Selected Flute Works by Sofia Gubaidulina”, is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the I.T.U. Social Sciences Institute, Dr. Erol Üçer Center for Advanced Studies in Music (MIAM). -

Vi Saint Petersburg International New Music Festival Artistic Director: Mehdi Hosseini

VI SAINT PETERSBURG INTERNATIONAL NEW MUSIC FESTIVAL ARTISTIC DIRECTOR: MEHDI HOSSEINI 21 — 25 MAY, 2019 facebook.com/remusik.org vk.com/remusikorg youtube.com/user/remusikorg twitter.com/remusikorg instagram.com/remusik_org SPONSORS & PARTNERS GENERAL PARTNERS 2019 INTERSECTIO A POIN OF POIN A The Organizing Committee would like to express its thanks and appreciation for the support and assistance provided by the following people: Eltje Aderhold, Karina Abramyan, Anna Arutyunova, Vladimir Begletsov, Alexander Beglov, Sylvie Bermann, Natalia Braginskaya, Denis Bystrov, Olga Chukova, Evgeniya Diamantidi, Valery Fokin, Valery Gergiev, Regina Glazunova, Andri Hardmeier, Alain Helou, Svetlana Ibatullina, Maria Karmanovskaya, Natalia Kopich, Roger Kull, Serguei Loukine, Anastasia Makarenko, Alice Meves, Jan Mierzwa, Tatiana Orlova, Ekaterina Puzankova, Yves Rossier, Tobias Roth Fhal, Olga Shevchuk, Yulia Starovoitova, Konstantin Sukhenko, Anton Tanonov, Hans Timbremont, Lyudmila Titova, Alexei Vasiliev, Alexander Voronko, Eva Zulkovska. 1 Mariinsky Theatre Concert Hall 4 Masterskaya M. K. Anikushina FESTIVAL CALENDAR Dekabristov St., 37 Vyazemsky Ln., 8 mariinsky.ru vk.com/sculptorstudio 2 New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre 5 “Lumiere Hall” creative space TUESDAY / 21.05 19:00 Mariinsky Theatre Concert Hall Fontanka River Embankment 49, Lit A Obvodnogo Kanala emb., 74А ensemble für neue musik zürich (Switzerland) alexandrinsky.ru lumierehall.ru 3 The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov 6 The Concert Hall “Jaani Kirik” Saint Petersburg State Conservatory Dekabristov St., 54A Glinka St., 2, Lit A jaanikirik.ru WEDNESDAY / 22.05 13:30 The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov conservatory.ru Saint Petersburg State Conservatory Composer meet-and-greet: Katharina Rosenberger (Switzerland) 16:00 Lumiere Hall Marcus Weiss, Saxophone (Switzerland) Ensemble for New Music Tallinn (Estonia) 20:00 New Stage of the Alexandrinsky Theatre Around the Corner (Spain, Switzerland) 4 Vyazemsky Ln. -

Behind the Scenes of the Fiery Angel: Prokofiev's Character

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ASU Digital Repository Behind the Scenes of The Fiery Angel: Prokofiev's Character Reflected in the Opera by Vanja Nikolovski A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved March 2018 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Brian DeMaris, Chair Jason Caslor James DeMars Dale Dreyfoos ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2018 ABSTRACT It wasn’t long after the Chicago Opera Company postponed staging The Love for Three Oranges in December of 1919 that Prokofiev decided to create The Fiery Angel. In November of the same year he was reading Valery Bryusov’s novel, “The Fiery Angel.” At the same time he was establishing a closer relationship with his future wife, Lina Codina. For various reasons the composition of The Fiery Angel endured over many years. In April of 1920 at the Metropolitan Opera, none of his three operas - The Gambler, The Love for Three Oranges, and The Fiery Angel - were accepted for staging. He received no additional support from his colleagues Sergi Diaghilev, Igor Stravinsky, Vladimir Mayakovsky, and Pierre Souvchinsky, who did not care for the subject of Bryusov’s plot. Despite his unsuccessful attempts to have the work premiered, he continued working and moved from the U.S. to Europe, where he continued to compose, finishing the first edition of The Fiery Angel. He married Lina Codina in 1923. Several years later, while posing for portrait artist Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva, the composer learned about the mysteries of a love triangle between Bryusov, Andrey Bely and Nina Petrovskaya. -

Sergei Prokofiev

Sergei Prokofiev Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev (/prɵˈkɒfiɛv/; Russian: Сергей Сергеевич Прокофьев, tr. Sergej Sergeevič Prokof'ev; April 27, 1891 [O.S. 15 April];– March 5, 1953) was a Russian composer, pianist and conductor. As the creator of acknowledged masterpieces across numerous musical genres, he is regarded as one of the major composers of the 20th century. His works include such widely heard works as the March from The Love for Three Oranges, the suite Lieutenant Kijé, the ballet Romeo and Juliet – from which "Dance of the Knights" is taken – and Peter and the Wolf. Of the established forms and genres in which he worked, he created – excluding juvenilia – seven completed operas, seven symphonies, eight ballets, five piano concertos, two violin concertos, a cello concerto, and nine completed piano sonatas. A graduate of the St Petersburg Conservatory, Prokofiev initially made his name as an iconoclastic composer-pianist, achieving notoriety with a series of ferociously dissonant and virtuosic works for his instrument, including his first two piano concertos. In 1915 Prokofiev made a decisive break from the standard composer-pianist category with his orchestral Scythian Suite, compiled from music originally composed for a ballet commissioned by Sergei Diaghilev of the Ballets Russes. Diaghilev commissioned three further ballets from Prokofiev – Chout, Le pas d'acier and The Prodigal Son – which at the time of their original production all caused a sensation among both critics and colleagues. Prokofiev's greatest interest, however, was opera, and he composed several works in that genre, including The Gambler and The Fiery Angel. Prokofiev's one operatic success during his lifetime was The Love for Three Oranges, composed for the Chicago Opera and subsequently performed over the following decade in Europe and Russia. -

TOCC0330DIGIBKLT.Pdf

GRIGORI FRID IN MEMORIAM by Elena Artamonova Grigori Samuilovich Frid (1915–2012) was a versatile Soviet-Russian composer, best known outside Russia for his ‘mono-operas’ (that is, with a single vocal soloist) The Diary of Anna Frank (1969) and The Letters of van Gogh (1975), which deservedly received a degree of international recognition. But they form only a small part of Frid’s extensive legacy, which includes three symphonies (1939, 1955, 1964), overtures and suites for symphony orchestra, four instrumental concertos (for violin, trombone and two for viola), a vocal-instrumental cycle after Federico Garcia Lorca, Poetry (1973), numerous chamber works for piano, violin, viola, cello, flute, oboe, clarinet and trumpet, five string quartets (1936, 1947, 1949, 1957, 1977), two piano quintets (1981, 1985), music for folk instruments, vocal and choral music, incidental music for various theatre and radio productions, film scores and music for children. The majority of these works have been performed, but hardly any have been recorded. From 1947 to 1963, Frid taught composition at the Moscow Conservatoire Music College. Among his students were the future composers Nikolai Korndorf, Maxim Dunaevsky, Alexandre Rabinovitch and Alexander Vustin.1 Frid was also a gifted writer, publishing six books (two books of essays on music, a novel and three books of memoirs), and a talented artist. From 1967 he regularly exhibited his paintings, which now hang in private collections in the USA, Finland, Germany, Israel and Russia. But even then the long and varied list of Frid’s accomplishments is not complete. For at least three generations of Muscovites, he is particularly well known as a tireless educator, as the presenter and one of the founding members of the Moskovskii Molodezhnyi Muzykal’nyi Klub (‘Moscow Musical Youth Club’) at the Composers’ Union (first of the USSR, and then of the Russian Federation) that Frid organised and led (with no financial reward) for almost half a century, from the day of its foundation on 21 October 1965 until his death. -

Experiments in Sound and Electronic Music in Koenig Books Isbn 978-3-86560-706-5 Early 20Th Century Russia · Andrey Smirnov

SOUND IN Z Russia, 1917 — a time of complex political upheaval that resulted in the demise of the Russian monarchy and seemingly offered great prospects for a new dawn of art and science. Inspired by revolutionary ideas, artists and enthusiasts developed innumerable musical and audio inventions, instruments and ideas often long ahead of their time – a culture that was to be SOUND IN Z cut off in its prime as it collided with the totalitarian state of the 1930s. Smirnov’s account of the period offers an engaging introduction to some of the key figures and their work, including Arseny Avraamov’s open-air performance of 1922 featuring the Caspian flotilla, artillery guns, hydroplanes and all the town’s factory sirens; Solomon Nikritin’s Projection Theatre; Alexei Gastev, the polymath who coined the term ‘bio-mechanics’; pioneering film maker Dziga Vertov, director of the Laboratory of Hearing and the Symphony of Noises; and Vladimir Popov, ANDREY SMIRNO the pioneer of Noise and inventor of Sound Machines. Shedding new light on better-known figures such as Leon Theremin (inventor of the world’s first electronic musical instrument, the Theremin), the publication also investigates the work of a number of pioneers of electronic sound tracks using ‘graphical sound’ techniques, such as Mikhail Tsekhanovsky, Nikolai Voinov, Evgeny Sholpo and Boris Yankovsky. From V eavesdropping on pianists to the 23-string electric guitar, microtonal music to the story of the man imprisoned for pentatonic research, Noise Orchestras to Machine Worshippers, Sound in Z documents an extraordinary and largely forgotten chapter in the history of music and audio technology. -

4932 Appendices Only for Online.Indd

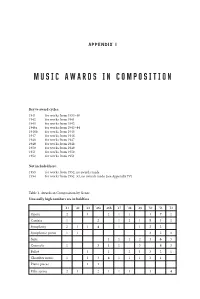

APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Key to award cycles: 1941 for works from 1934–40 1942 for works from 1941 1943 for works from 1942 1946a for works from 1943–44 1946b for works from 1945 1947 for works from 1946 1948 for works from 1947 1949 for works from 1948 1950 for works from 1949 1951 for works from 1950 1952 for works from 1951 Not included here: 1953 for works from 1952, no awards made 1954 for works from 1952–53, no awards made (see Appendix IV) Table 1. Awards in Composition by Genre Unusually high numbers are in boldface ’41 ’42 ’43 ’46a ’46b ’47 ’48 ’49 ’50 ’51 ’52 Opera2121117 2 Cantata 1 2 1 2 1 5 32 Symphony 2 1 1 4 1122 Symphonic poem 1 1 3 2 3 Suite 111216 3 Concerto 1 3 1 1 3 4 3 Ballet 1 1 21321 Chamber music 1 1 3 4 11131 Piano pieces 1 1 Film scores 21 2111 1 4 APPENDIX I MUSIC AWARDS IN COMPOSITION Songs 2121121 6 3 Art songs 1 2 Marches 1 Incidental music 1 Folk instruments 111 Table 2. Composers in Alphabetical Order Surnames are given in the most common transliteration (e.g. as in Wikipedia); first names are mostly given in the familiar anglicized form. Name Alternative Spellings/ Dates Class and Year Notes Transliterations of Awards 1. Afanasyev, Leonid 1921–1995 III, 1952 2. Aleksandrov, 1883–1946 I, 1942 see performers list Alexander for a further award (Appendix II) 3. Aleksandrov, 1888–1982 II, 1951 Anatoly 4. -

Opera & Ballet 2017

12mm spine THE MUSIC SALES GROUP A CATALOGUE OF WORKS FOR THE STAGE ALPHONSE LEDUC ASSOCIATED MUSIC PUBLISHERS BOSWORTH CHESTER MUSIC OPERA / MUSICSALES BALLET OPERA/BALLET EDITION WILHELM HANSEN NOVELLO & COMPANY G.SCHIRMER UNIÓN MUSICAL EDICIONES NEW CAT08195 PUBLISHED BY THE MUSIC SALES GROUP EDITION CAT08195 Opera/Ballet Cover.indd All Pages 13/04/2017 11:01 MUSICSALES CAT08195 Chester Opera-Ballet Brochure 2017.indd 1 1 12/04/2017 13:09 Hans Abrahamsen Mark Adamo John Adams John Luther Adams Louise Alenius Boserup George Antheil Craig Armstrong Malcolm Arnold Matthew Aucoin Samuel Barber Jeff Beal Iain Bell Richard Rodney Bennett Lennox Berkeley Arthur Bliss Ernest Bloch Anders Brødsgaard Peter Bruun Geoffrey Burgon Britta Byström Benet Casablancas Elliott Carter Daniel Catán Carlos Chávez Stewart Copeland John Corigliano Henry Cowell MUSICSALES Richard Danielpour Donnacha Dennehy Bryce Dessner Avner Dorman Søren Nils Eichberg Ludovico Einaudi Brian Elias Duke Ellington Manuel de Falla Gabriela Lena Frank Philip Glass Michael Gordon Henryk Mikolaj Górecki Morton Gould José Luis Greco Jorge Grundman Pelle Gudmundsen-Holmgreen Albert Guinovart Haflidi Hallgrímsson John Harbison Henrik Hellstenius Hans Werner Henze Juliana Hodkinson Bo Holten Arthur Honegger Karel Husa Jacques Ibert Angel Illarramendi Aaron Jay Kernis CAT08195 Chester Opera-Ballet Brochure 2017.indd 2 12/04/2017 13:09 2 Leon Kirchner Anders Koppel Ezra Laderman David Lang Rued Langgaard Peter Lieberson Bent Lorentzen Witold Lutosławski Missy Mazzoli Niels Marthinsen Peter Maxwell Davies John McCabe Gian Carlo Menotti Olivier Messiaen Darius Milhaud Nico Muhly Thea Musgrave Carl Nielsen Arne Nordheim Per Nørgård Michael Nyman Tarik O’Regan Andy Pape Ramon Paus Anthony Payne Jocelyn Pook Francis Poulenc OPERA/BALLET André Previn Karl Aage Rasmussen Sunleif Rasmussen Robin Rimbaud (Scanner) Robert X. -

Marina Frolova-Walker from Modernism to Socialist

Marina Frolova-Walker From modernism to socialist... Marina Frolova-Walker FROM MODERNISM TO SOCIALIST REALISM IN FOUR YEARS: MYASKOVSKY AND ASAFYEV Abstract: Two outstanding personalities of the Soviet musical life in the 1920’s, the composer Nikolay Myaskovsky and the musicologist Boris Asafyev, both exponents of modernism, made volte-faces towards traditionalism at the beginning of the next decade. Myaskovsky’s Symphony no. 12 (1931) and Asafyev’s ballet The Flames of Paris (1932) became models for Socialist Realism in music. The letters exchanged between the two men testify to the former’s uneasiniess at the great success of those of his works he considered not valuable enough, whereas the latter was quite satisfied with his new career as composer. The examples of Myaskovsky and Asafyev show that early Soviet modernists made their move away from avantgarde creativity well before they faced any real danger from the bureacracy. Key-Words: Socialist Realism, Nikolay Myaskovsky, Boris Asafyev From 1929 to 1932, Stalin’s shock-workers were fuelled by the slogan, "Fulfil the Five-Year Plan in four years!" The years of foreign invasions and White reaction had devastated Russia’s economy; now from a base of almost nothing, Stalin set out to transform the Soviet Union into a new industrial great power. Alongside industrialization and collectivisation, the field of culture also underwent a transformation, from the pluralistic ferment of experimentation of the post-revolutionary decade to the semi-desert of Socialist Realism. First the self-proclaimed "proletarian" cultural organisations were used to bludgeon other groups out of existence. Then the same proletarian organisations were themselves dissolved in favour of state unions of writers, painters and com- posers. -

Prokofiev, Sergey (Sergeyevich)

Prokofiev, Sergey (Sergeyevich) (b Sontsovka, Bakhmutsk region, Yekaterinoslav district, Ukraine, 11/23 April 1891; d Moscow, 5 March 1953). Russian composer and pianist. He began his career as a composer while still a student, and so had a deep investment in Russian Romantic traditions – even if he was pushing those traditions to a point of exacerbation and caricature – before he began to encounter, and contribute to, various kinds of modernism in the second decade of the new century. Like many artists, he left his country directly after the October Revolution; he was the only composer to return, nearly 20 years later. His inner traditionalism, coupled with the neo-classicism he had helped invent, now made it possible for him to play a leading role in Soviet culture, to whose demands for political engagement, utility and simplicity he responded with prodigious creative energy. In his last years, however, official encouragement turned into persecution, and his musical voice understandably faltered. 1. Russia, 1891–1918. 2. USA, 1918–22. 3. Europe, 1922–36. 4. The USSR, 1936–53. WORKS BIBLIOGRAPHY DOROTHEA REDEPENNING © Oxford University Press 2005 How to cite Grove Music Online 1. Russia, 1891–1918. (i) Childhood and early works. (ii) Conservatory studies and first public appearances. (iii) The path to emigration. © Oxford University Press 2005 How to cite Grove Music Online Prokofiev, Sergey, §1: Russia: 1891–1918 (i) Childhood and early works. Prokofiev grew up in comfortable circumstances. His father Sergey Alekseyevich Prokofiev was an agronomist and managed the estate of Sontsovka, where he had gone to live in 1878 with his wife Mariya Zitkova, a well-educated woman with a feeling for the arts.