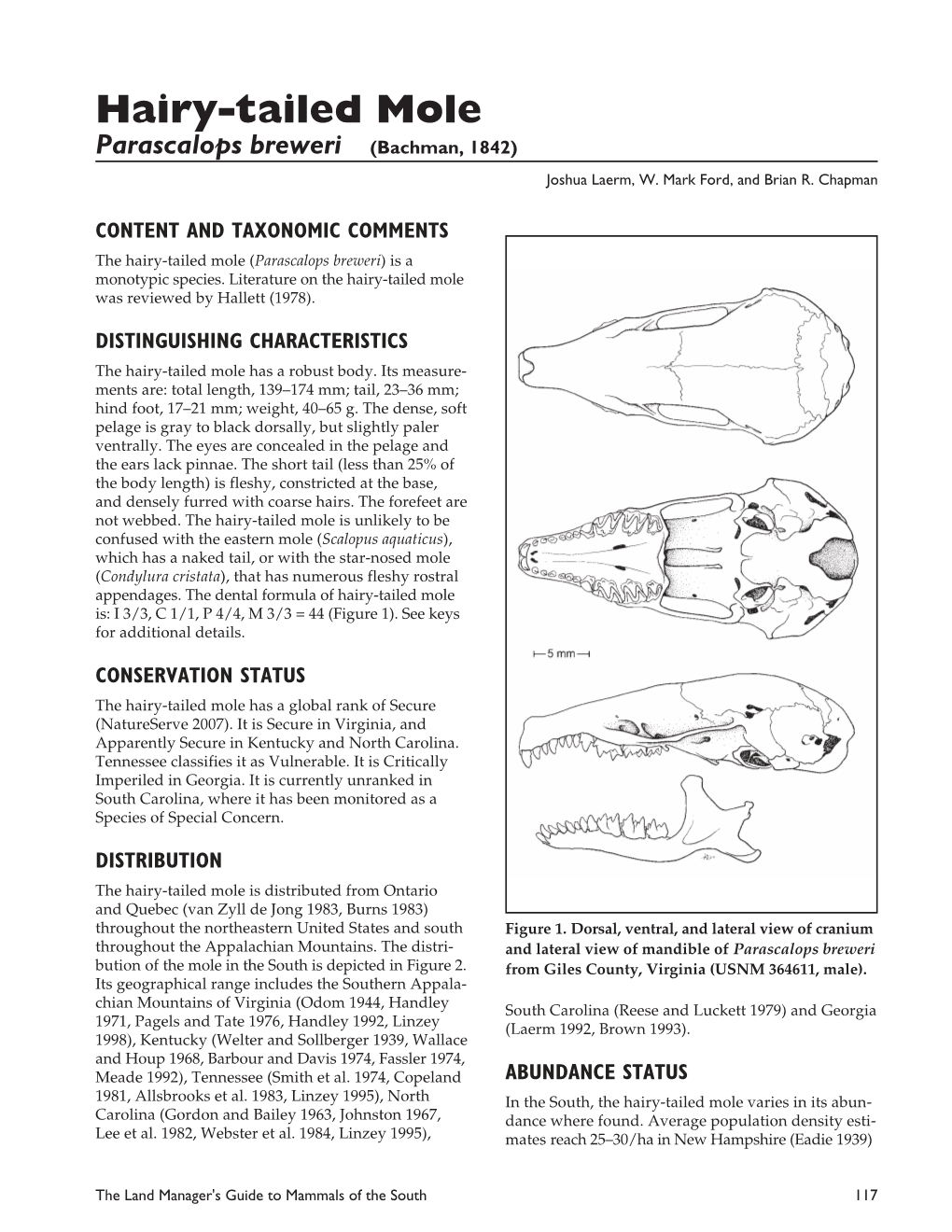

Hairy-Tailed Mole, Parascalops Breweri

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAMMALS of OHIO F I E L D G U I D E DIVISION of WILDLIFE Below Are Some Helpful Symbols for Quick Comparisons and Identfication

MAMMALS OF OHIO f i e l d g u i d e DIVISION OF WILDLIFE Below are some helpful symbols for quick comparisons and identfication. They are located in the same place for each species throughout this publication. Definitions for About this Book the scientific terms used in this publication can be found at the end in the glossary. Activity Method of Feeding Diurnal • Most active during the day Carnivore • Feeds primarily on meat Nocturnal • Most active at night Herbivore • Feeds primarily on plants Crepuscular • Most active at dawn and dusk Insectivore • Feeds primarily on insects A word about diurnal and nocturnal classifications. Omnivore • Feeds on both plants and meat In nature, it is virtually impossible to apply hard and fast categories. There can be a large amount of overlap among species, and for individuals within species, in terms of daily and/or seasonal behavior habits. It is possible for the activity patterns of mammals to change due to variations in weather, food availability or human disturbances. The Raccoon designation of diurnal or nocturnal represent the description Gray or black in color with a pale most common activity patterns of each species. gray underneath. The black mask is rimmed on top and bottom with CARNIVORA white. The raccoon’s tail has four to six black or dark brown rings. habitat Raccoons live in wooded areas with Tracks & Skulls big trees and water close by. reproduction Many mammals can be elusive to sighting, leaving Raccoons mate from February through March in Ohio. Typically only one litter is produced each year, only a trail of clues that they were present. -

Controlling the Eastern Mole

Agriculture and Natural Resources FSA9095 Controlling the Eastern Mole Dustin Blakey Introduction known about the Eastern Mole, and County Extension Agent successful control in landscapes Agriculture Few things in this world are requires a basic understanding of more frustrating than spending valu their biology. able time and money on a landscape Rebecca McPeake only to have it torn up by wildlife. Mole Biology Associate Professor and Moles’ underground habits aerate the Extension Wildlife soil and reduce grubs, but their Moles spend most of their lives Specialist digging is cause for homeowner underground feeding on invertebrate complaints, making them one of the animals living in the soil. A mole’s most destructive mammals that can diet sharply reflects the diversity of inhabit our landscapes. the fauna found in its environment. In Arkansas, moles primarily feed on earthworms, grubs and other inverte brates. Moles lack the dental struc ture to chew plant material (seeds, roots, etc.) for food and, as a result, subsist strictly as carnivores. Occasionally moles will cut surface vegetation and bring it down to their nest, as bedding, but this is not eaten. Figure 1. Rarely seen on the surface, moles are uniquely designed for their underground existence. Photo printed with permission by Ann and Rob Simpson. Contrary to popular belief, moles are not rodents. Mice, squirrels and gophers are all rodents. Moles are insectivores in the family Talpidae. Figure 2. Moles lack the dental structure This animal family survives by to chew plant material and subsist feeding on invertebrate prey. There mostly on earthworms and other invertebrates. are seven species of moles in North America, but the Eastern Mole Moles are well-adapted to living (Scalopus aquaticus L.) is the species underground. -

Water Shrew & Endangered Species Sorex Palustris

Natural Heritage Water Shrew & Endangered Species Sorex palustris Program State Status: Special Concern www.mass.gov/nhesp Federal Status: None Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife DESCRIPTION: The Water Shrew is the largest long- tailed shrew in New England. It measures 144-158 mm (5.7-6.2 in) in length, with its long tail accounting for more than half of its total length, and weighs from 10-16 g (approximately 1/3 oz). The unique feature of the Water Shrew is its big “feathered” hind foot. The third and fourth toes of the Water Shrew’s hind feet are slightly webbed, and all toes as well as the foot itself have conspicuous stiff hairs along the sides. Both the webbing and the fringe of hairs increase the Water Shrew’s swimming efficiency. The male and female Water Shrew are colored alike, Illustration from DeGraaf and Rudis, 1986. equal in size, and show slight seasonal color variation. In winter, the Water Shrew is glossy, gray-black above tipped with silver, and silvery buff below, becoming adults. The Water Shrew is slender with a long, narrow lighter on the throat and chin. It has whitish hands and snout that is highly movable and incessantly rotating. Its feet, and a long, bicolored (i.e., lighter beneath, darker eyes are minute but visible, and its ears are small and above) tail covered with short, brown bristles. In hidden in velvety fur. Females have six mammae. summer, its pelage (fur) is more brownish above and slightly paler below, with a less frosted appearance. This species is especially adapted for semi-aquatic life. -

Small Mammal Survey of the Nulhegan Basin Division of the Silvio 0

Small Mammal Survey of the Nulhegan Basin Division of the Silvio 0. Conte NFWR and the State of Vermont's West Mountain Wildlife Management Area, Essex County Vermont • Final Report March 15, 2001 C. William Kilpatrick Department of Biology University of Vermont Burlington, Vermont 05405-0086 A total of 19 species of small mammals were documented from the Nulhegan Basin Division of the Silvio 0. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge (NFWR) and the West Mountain Wildlife Management Area Seventeen of these species had previously been documented from Essex County, but specimens of the little brown bat (Jr{yotis lucifugu.s) and the northern long-eared bat (M septentrionalis) represent new records for this county. Although no threatened or endangered species were found in this survey, specimens of two rare species were captured including a water shrew (Sorex palustris) and yellow-nosed voles (Microtus chrotorrhinus). Population densities were relatively low as reflected in a mean trap success of 7 %, and the number of captures of two species, the short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda) and the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus), were noticeably low. Low population densities were observed in northern hardwood forests, a lowland spruce-fir forest, a black spruce/dwarf shrub bog, and most clear-cuts, whereas the high population densities were found along talus slopes, in a mixed hardwood forest with some • rock ledges, and in a black spruce swamp. The highest species diversity was found in a montane yellow birch-red spruce forest, a black spruce swamp, a beaver/sedge meadow, and a talus slope within a mixed forest. -

Species of Conservation Concern SC SWAP 2015

Supplemental Volume: Species of Conservation Concern SC SWAP 2015 Moles Guild Hairy-tailed Mole (Parascalops breweri) Star-nosed Mole (Condylura cristata) Contributors (2005): Mary Bunch (SCDNR), Mark Ford (VA Tech), and David Webster (UNC-W) Reviewed and Edited (2012): Steve Fields (Culture and Heritage Museums) and David Webster (UNC-W) DESCRIPTION Taxonomy and Basic Description Three species of moles occur in South Carolina. These include the eastern mole, (Scalopus aquaticus) which is widely distributed and common. The other 2 species, the star-nosed mole (Condylura cristata) and hairy-tailed mole (Parascalops breweri), are less commonly encountered in South Carolina. All 3 possess velvety fur; eyes that are small and concealed in the fur; and large well-developed forelimbs with backward facing palms and long claws. They also lack external ear structures. The star-nosed mole was first described by Linnaeus in Star-nosed Mole Photo courtesy of ATBI 1758. Two subspecies are recognized for the star-nosed mole: Condylura cristata cristata and Condylura cristata parva. Star-nosed moles in South Carolina are considered to be C. c. parva (Peterson and Yates 1980). As the name implies, the rostrum of the star-nosed mole is star-like and consists of 22 fleshy appendages. Total length of this species ranges from 153 to 238 mm (6.24 to 9.3 in.). The moderately haired tail is approximately one-third to one- half the body length. The fur is black or a black-brown on the back (Peterson and Yates 1980; Webster et al. 1985; Laerm et al. 2005a). The hairy-tailed mole, first described by Bachman Hairy-tailed Mole Photo by E.B. -

Effective Mole Control Gary L

Extension W-11-2002 FSchool ofactSheet Natural Resources, 2021 Coffey Road, Columbus, Ohio 43210 Effective Mole Control Gary L. Comer, Jr., Extension Agent, Water Quality & Natural Resources, Logan County Amanda D. Rodewald, Assistant Professor of Wildlife Ecology and Extension Specialist, School of Natural Resources, The Ohio State University here are six species of moles in North America, and Tthree of these may occur in your yard (Eastern Mole, Hairy-tailed Mole, and Star-nosed Mole). Of these, the East- ern Mole (Scalopus aquaticus) is most common in Ohio. Moles are about the size of chipmunks (6-8 inches in length) and can weigh three to six ounces. Each year a mole can have one lit- ter of two to six young, depending on the health of the female. Gestation lasts about five to six weeks, which means that you can expect litters anywhere from mid-April through May. Be- lieve it or not, young moles have less than a 50% chance of surviving long enough to reproduce. Moles are insectivores (they eat insects), and they may con- trol some insect outbreaks. However, mole activity can also cause considerable damage to lawns. This damage is usually in the form of tunnels and/or mounds in lawn that can be un- sightly, disturb root systems, and provide cover or travel lanes for other small mammals. Often mole damage could be reduced or eliminated by not encroaching If you are like most homeowners, you are probably confused on the mole natural habitat. This wood lot is an example of wildlife by all of the conflicting “advice” on mole control. -

Coccidia (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) of the Mammalian Order Insectivora

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of 2000 Coccidia (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) of the Mammalian Order Insectivora Donald W. Duszynski University of New Mexico, [email protected] Steve J. Upton Kansas State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs Part of the Parasitology Commons Duszynski, Donald W. and Upton, Steve J., "Coccidia (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) of the Mammalian Order Insectivora" (2000). Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology. 196. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/parasitologyfacpubs/196 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Parasitology, Harold W. Manter Laboratory of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications from the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SPECIAL PUBLICATION THE MUSEUM OF SOUTHWESTERN BIOLOGY NUMBER 4, pp. 1-67 30 OCTOBER 2000 Coccidia (Apicomplexa: Eimeriidae) of the Mammalian Order Insectivora DONALD W. DUSZYNSKI AND STEVE J. UPTON TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Materials and Methods 2 Results 3 Family Erinaceidae Erinaceus Eimeria ostertagi 3 E. perardi 4 Isospora erinacei 4 I. rastegaievae 5 I. schmaltzi 6 Hemiechinus E. auriti 7 E. bijlikuli 7 Hylomys E. bentongi 7 I. hylomysis 8 Family Soricidae Crocidura E. firestonei 8 E. leucodontis 9 E. milleri 9 E. ropotamae 10 Suncus E. darjeelingensis 10 E. murinus...................................................................................................................... 11 E. suncus 12 Blarina E. blarinae 13 E. brevicauda 13 I. brevicauda 14 Cryptotis E. -

Moles, Voles and Shrews

MlMoles, VVloles, and Shrews, Oh my! Eastern Mole Scalopus aquaticus Eastern Mole • 4 ½ to 7 inches long • Up to 5 ounces • Insectivora: Eats insects and invertebrates; not plants • Solitary • 2 to 5 young once a year •Diggps up to 150 ft. per da y. Visible tunnels likely feeding tunnels Eastern Mole • Control Measures • Toxicants and fumigants • Food Source Removal • Barriers • “Kill Traps” – use caution • Pit trap Eastern Mole • PIT TRAP • Find an active runway • Uncover enough to insert a #10 size can flush with tunnel floor • Fill and pack around can • Plug tunnel on both sides of can Eastern Mole • Cover the pit with a board • If no mole within 1 or 2 days, relocate trap Eastern Mole • Alternative: Live and let Live •Why? Eastern Mole • “Moles are important predators of insect larvae and other invertebrates; they can profoundly impact the communities of their prey. They also act to aerate and turn soil where they live through their extensive tunneling activities” – Gorog A. 1999. “Sca lopus Aqua ticus, Animal Diversity Web Pine Vole Pitymys pinetorum Pine Vole • Less than 2 ounces • 3 to 4 inches • Fossorial • Rodentia • Herbivore • Prolific • Destructive Vole Salad Bar Pine Vole • Damage Control • Eliminate Ground Cover • Soil Tillage • Plant Selection • Chemicals ? • Exclusion Hardware Cloth Barrier Hardware Cloth Barrier Hardware Cloth Barrier Pine Vole • Damage Control • Traps Vole Trap • Locate the Tunnel Vole Trap • Excavate • Bait the Trap • Lay flush with tunnel bottom and at right angles to the tunnel line, • or-- Vole Trap • Just lay trap on the surface Vole Trap • Cover and Weight • And Wait Pine Vole • Damage Control • Predation Vole Predators Ferocious Predator In His Lair Least Shrew Cryptotis parva Least Shrew • 2 ½ to 4 inches • Less than ¼ ounce • Insectivora • Same diet as mole • Some seeds and fruit • Same predators • Slightly venomous • Harmless to garden Moles, Voles, and Shrews, Oh my! THE END !!. -

Checklist of Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals of New York

CHECKLIST OF AMPHIBIANS, REPTILES, BIRDS AND MAMMALS OF NEW YORK STATE Including Their Legal Status Eastern Milk Snake Moose Blue-spotted Salamander Common Loon New York State Artwork by Jean Gawalt Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Fish and Wildlife Page 1 of 30 February 2019 New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Division of Fish and Wildlife Wildlife Diversity Group 625 Broadway Albany, New York 12233-4754 This web version is based upon an original hard copy version of Checklist of the Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds and Mammals of New York, Including Their Protective Status which was first published in 1985 and revised and reprinted in 1987. This version has had substantial revision in content and form. First printing - 1985 Second printing (rev.) - 1987 Third revision - 2001 Fourth revision - 2003 Fifth revision - 2005 Sixth revision - December 2005 Seventh revision - November 2006 Eighth revision - September 2007 Ninth revision - April 2010 Tenth revision – February 2019 Page 2 of 30 Introduction The following list of amphibians (34 species), reptiles (38), birds (474) and mammals (93) indicates those vertebrate species believed to be part of the fauna of New York and the present legal status of these species in New York State. Common and scientific nomenclature is as according to: Crother (2008) for amphibians and reptiles; the American Ornithologists' Union (1983 and 2009) for birds; and Wilson and Reeder (2005) for mammals. Expected occurrence in New York State is based on: Conant and Collins (1991) for amphibians and reptiles; Levine (1998) and the New York State Ornithological Association (2009) for birds; and New York State Museum records for terrestrial mammals. -

Discarded Bottles As a Source of Shrew Species Distributional Data Along an Elevational Gradient in the Southern Appalachians Author(S): M

Discarded Bottles as a Source of Shrew Species Distributional Data along an Elevational Gradient in the Southern Appalachians Author(s): M. Patrick Brannon, Melissa A. Burt, David M. Bost and Marguerite C. Caswell Source: Southeastern Naturalist, 9(4):781-794. 2010. Published By: Humboldt Field Research Institute DOI: 10.1656/058.009.0412 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1656/058.009.0412 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is an electronic aggregator of bioscience research content, and the online home to over 160 journals and books published by not-for-profit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. 2010 SOUTHEASTERN NATURALIST 9(4):781–794 Discarded Bottles as a Source of Shrew Species Distributional Data along an Elevational Gradient in the Southern Appalachians M. Patrick Brannon1,*, Melissa A. Burt1, David M. Bost1, and Marguerite C. Caswell1 Abstract - Discarded bottles were inspected for skeletal remains at 220 roadside sites along the southeastern Blue Ridge escarpment of North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia as a technique to examine the regional distributions of shrews. -

Head-Body Length Variation in the Mole-Shrew (Anourosorex Squamipes) in Relation to Annual Temperature and Elevation

NORTH-WESTERN JOURNAL OF ZOOLOGY 7 (1): pp.47-54 ©NwjZ, Oradea, Romania, 2011 Article No.: 111103 www.herp-or.uv.ro/nwjz Head-body length variation in the mole-shrew (Anourosorex squamipes) in relation to annual temperature and elevation Wen Bo LIAO*, Cai Quan ZHOU* & Jin Chu HU Institute of Rare Animals and Plants, China West Normal University, Nanchong 637009, China * Corresponding authors, W.B. Liao, e-mail: [email protected]; C.Q. Zhou, e-mail: [email protected] Received: 09. April 2010 / Accepted: 17. January 2011 / Available online: 25. January 2011 Abstract. Temperature change may affect physiology, distribution, morphology and adaptation of animals. Using individuals captured in Nanchong and Laojunshan Nature Reserve of Sichuan province in western China, we tested head-body length variation in the mole-shrew (Anourosorex squamipes) in relation to annual temperature and elevation. Our results indicate that head-body length of both males and females decreases with decreasing ambient temperature along an altitudinal gradient. Likewise, there is significant monthly variation in head-body length, with individuals in warmer months being larger than that colder ones. The seasonal variation in head-body length suggests the higher predator risk and lower food availability in cold months. Keywords: Body size, Anourosorex squamipes, temperature, elevation. Introduction size and temperature among populations. For ex- ample, body size of the short-tailed shrew (Blarina Body size has long been considered one of the brevicauda) negatively correlates with ambient most important traits of an organism because it in- temperature (Jones & Findlay 1954, Huggins & fluences nearly every aspect of its life history (Pe- Kennedy 1989). -

Notes on the Habits of Mice, Moles and Shrews

West Virginia Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Davis College of Agriculture, Natural Resources Station Bulletins And Design 1-1-1908 Notes on The aH bits of Mice, Moles and Shrews : a Preliminary Report Fred E. Brooks Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/ wv_agricultural_and_forestry_experiment_station_bulletins Digital Commons Citation Brooks, Fred E., "Notes on The aH bits of Mice, Moles and Shrews : a Preliminary Report" (1908). West Virginia Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station Bulletins. 113. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wv_agricultural_and_forestry_experiment_station_bulletins/113 This Bulletin is brought to you for free and open access by the Davis College of Agriculture, Natural Resources And Design at The Research Repository @ WVU. It has been accepted for inclusion in West Virginia Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station Bulletins by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WEST VIRGINIA UNIVERSITY AGRICULTURAL EXPERIHENT STATION MORGANTOWN, W. VA. Bulletin 113. January, 1908. Notes on the Habits of Mice, Moles and Shrews. (A Preliminary Report.) By FRED E. BROOKS. [The Bulletins and Reports of this Station will be mailed free to any citizen of "West Virginia upon written application. Address Director of Agricultural Experiment Station, Morgantown, W. Va.] THE REGENTS OF THE WEST VIRGINIA UNIVERSITY Name of Regent. P. 0. Address. Hon. C. M. Babb Falls, W. Va. Hon. J. B. Finley Parkersburg, W. Va. Hon. D. C. Gallaher Charleston, "W. Va. Hon. E. M. Grant Morgantown, W. Va. Hon. C. E. Haworth Huntington, "W. Va Hon. C. P. McNell Wheeling, W. Va. Hon. L. J. Williams Lewisburg, W.