Read Excerpt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extreme Leadership Leaders, Teams and Situations Outside the Norm

JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 3 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:53:29 2013 Extreme Leadership Leaders, Teams and Situations Outside the Norm Edited by Cristina M. Giannantonio Amy E. Hurley-Hanson Associate Professors of Management, George L. Argyros School of Business and Economics, Chapman University, USA NEW HORIZONS IN LEADERSHIP STUDIES Edward Elgar Cheltenham, UK + Northampton, MA, USA Columns Design XML Ltd / Job: Giannantonio-New_Horizons_in_Leadership_Studies / Division: prelims /Pg. Position: 1 / Date: 30/10 JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 4 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:53:29 2013 © Cristina M. Giannantonio andAmy E. Hurley-Hanson 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Published by Edward Elgar Publishing Limited The Lypiatts 15 Lansdown Road Cheltenham Glos GL50 2JA UK Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc. William Pratt House 9 Dewey Court Northampton Massachusetts 01060 USA A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Control Number: 2013946802 This book is available electronically in the ElgarOnline.com Business Subject Collection, E-ISBN 978 1 78100 212 4 ISBN 978 1 78100 211 7 (cased) Typeset by Columns Design XML Ltd, Reading Printed and bound in Great Britain by T.J. International Ltd, Padstow Columns Design XML Ltd / Job: Giannantonio-New_Horizons_in_Leadership_Studies / Division: prelims /Pg. Position: 2 / Date: 30/10 JOBNAME: Giannantonio PAGE: 1 SESS: 5 OUTPUT: Wed Oct 30 14:57:46 2013 14. Extreme leadership as creative leadership: reflections on Francis Ford Coppola in The Godfather Charalampos Mainemelis and Olga Epitropaki INTRODUCTION How do extreme leadership situations arise? According to one view, they are triggered by environmental factors that have nothing or little to do with the leader. -

108 Kansas History “Facing This Vast Hardness”: the Plains Landscape and the People Shaped by It in Recent Kansas/Plains Film

Premiere of Dark Command, Lawrence, 1940. Courtesy of the Douglas County Historical Society, Watkins Museum of History, Lawrence, Kansas. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 38 (Summer 2015): 108–135 108 Kansas History “Facing This Vast Hardness”: The Plains Landscape and the People Shaped by It in Recent Kansas/Plains Film edited and introduced by Thomas Prasch ut the great fact was the land itself which seemed to overwhelm the little beginnings of human society that struggled in its sombre wastes. It was from facing this vast hardness that the boy’s mouth had become so “ bitter; because he felt that men were too weak to make any mark here, that the land wanted to be let alone, to preserve its own fierce strength, its peculiar, savage kind of beauty, its uninterrupted mournfulness” (Willa Cather, O Pioneers! [1913], p. 15): so the young boy Emil, looking out at twilight from the wagon that bears him backB to his homestead, sees the prairie landscape with which his family, like all the pioneers scattered in its vastness, must grapple. And in that contest between humanity and land, the land often triumphed, driving would-be settlers off, or into madness. Indeed, madness haunts the pages of Cather’s tale, from the quirks of “Crazy Ivar” to the insanity that leads Frank Shabata down the road to murder and prison. “Prairie madness”: the idea haunts the literature and memoirs of the early Great Plains settlers, returns with a vengeance during the Dust Bowl 1930s, and surfaces with striking regularity even in recent writing of and about the plains. -

False Authenticity in the Films of Woody Allen

False Authenticity in the Films of Woody Allen by Nicholas Vick November, 2012 Director of Thesis: Amanda Klein Major Department: English Woody Allen is an auteur who is deeply concerned with the visual presentation of his cityscapes. However, each city that Allen films is presented in such a glamorous light that the depiction of the cities is falsely authentic. That is, Allen's cityscapes are actually unrealistic recreations based on his nostalgia or stilted view of the city's culture. Allen's treatment of each city is similar to each other in that he strives to create a cinematic postcard for the viewer. However, differing themes and characteristics emerge to define Allen's optimistic visual approach. Allen's hometown of Manhattan is a place where artists, intellectuals, and writers can thrive. Paris denotes a sense of nostalgia and questions the power behind it. Allen's London is primarily concerned with class and the social imperative. Finally, Barcelona is a haven for physicality, bravado, and sex but also uncertainty for American travelers. Despite being in these picturesque and dynamic locations, happiness is rarely achieved for Allen's characters. So, regardless of Allen's dreamy and romanticized visual treatment of cityscapes and culture, Allen is a director who operates in a continuous state of contradiction because of the emotional unrest his characters suffer. False Authenticity in the Films of Woody Allen A Thesis Presented To the Faculty of the Department of English East Carolina University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MA English by Nicholas Vick November, 2012 © Nicholas Vick, 2012 False Authenticity in the Films of Woody Allen by Nicholas Vick APPROVED BY: DIRECTOR OF DISSERTATION/THESIS: _______________________________________________________ Dr. -

A Study of Musical Affect in Howard Shore's Soundtrack to Lord of the Rings

PROJECTING TOLKIEN'S MUSICAL WORLDS: A STUDY OF MUSICAL AFFECT IN HOWARD SHORE'S SOUNDTRACK TO LORD OF THE RINGS Matthew David Young A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC IN MUSIC THEORY May 2007 Committee: Per F. Broman, Advisor Nora A. Engebretsen © 2007 Matthew David Young All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Per F. Broman, Advisor In their book Ten Little Title Tunes: Towards a Musicology of the Mass Media, Philip Tagg and Bob Clarida build on Tagg’s previous efforts to define the musical affect of popular music. By breaking down a musical example into minimal units of musical meaning (called musemes), and comparing those units to other musical examples possessing sociomusical connotations, Tagg demonstrated a transfer of musical affect from the music possessing sociomusical connotations to the object of analysis. While Tagg’s studies have focused mostly on television music, this document expands his techniques in an attempt to analyze the musical affect of Howard Shore’s score to Peter Jackson’s film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings Trilogy. This thesis studies the ability of Shore’s film score not only to accompany the events occurring on-screen, but also to provide the audience with cultural and emotional information pertinent to character and story development. After a brief discussion of J.R.R. Tolkien’s description of the cultures, poetry, and music traits of the inhabitants found in Middle-earth, this document dissects the thematic material of Shore’s film score. -

Pdf 337.65 K

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY STUDIES IN ART AND TECHNOLOGY ISSN: 2735-4342 VOLUME 3, ISSUE 2, 2020, 7 – 14. https://ijmsat.journals.ekb.eg/ THE INFLUENCE OF REMBRANDT ON COMPOSITION OF IMAGE IN MOVIES Basma Khalil Ibrahim KHALIL * Decoration Department, Faculty of Fine Arts, Alexandria University, Egypt Abstract There is no doubt that the Dutch plastic artist Rembrandt had his style separate from the artists of his time, and he influenced almost every field of Dutch art, and he was inspired by artists around the world and this influence was repeated and continued in no way in the history of art, and this influence extended until The present time includes the fields of arts, especially in cinema. For filmmakers, as well as generations of art enthusiasts, Rembrandt is the master of light and shadow, and his style of light distribution in painting has influenced many photographers and lighting designers in the history of cinema. In a study conducted to clarify the relationship between plastic art (photography and cinema or motion picture), some critics and filmmakers believed that without the paintings of the Dutch master of photography in the seventeenth century, many masterpieces of cinematography would not exist. Since the beginning of the fifteenth century, artists have used light as if it were a living element, invoking it and using it persuasively to create their own vision, light and shadow, essential components of the art of photography and cinematography, were given for the first time their true freedom by the Dutch artist Rembrandt and expanded with enthusiasm in The world of imagination, and his art was a source of inspiration for filmmakers in building the composition of the shots and the freedom of movement was given to the camera poetically through it, and he set the standard of the camera that it should be. -

Recommended Reading 2010

American History 2010 Official Sponsors Ever worry that you’ve forgotten Dollar General, Dollar General Literacy everything you learned in school? Brush Foundation Wondering what to read in up with these American novels and history HarperCollins Publishers, Avon A, Harper your book club? books. Paperbacks, Harper Perennial Hyperion/Voice 1. Founding Mothers: The Women Simon & Schuster Let us help! Who Raised Our Nation by Cokie Unbridled Books Roberts $14.99 2. Moloka’i by Alan Brennert $14.99 3. The Worst Hard Time: The Untold Story of Those Who Survived the Great American Dust Bowl by Park Road Books Timothy Egan $14.95 Park Road Shopping Center 4. The Devil in the White City 4139 Park Road Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Charlotte, NC 28209 Fair that Changed America by Erik Larson $15.00 5. The River of Doubt: Theodore Roosevelt's Darkest Journey by Candice Millard $15.00 6. Impatient with Desire by Gabrielle Burton $22.99 7. Ahab's Wife: Or, The Star-Gazer by Here are 4 lists of books that would Sena Jeter Naslund $15.95 make for great discussions at your 8. The Tea Rose by Jennifer Donnelly $14.95 book club, chosen by the officers of 9. All the President's Men by Carl the Charlotte chapter of the Women’s Bernstein and Bob Woodward $7.99 National Book Association 10. Assassination Vacation by Sarah Vowell $15.00 11. Confederates in the Attic: The Women’s National Book Association Dispatches from the Unfinished brings together people who share an Park Road Books carries all of these Civil War by Tony Horwitz $16.00 interest in books and reading. -

The Making of Hollywood Production: Televising and Visualizing Global Filmmaking in 1960S Promotional Featurettes

The Making of Hollywood Production: Televising and Visualizing Global Filmmaking in 1960s Promotional Featurettes by DANIEL STEINHART Abstract: Before making-of documentaries became a regular part of home-video special features, 1960s promotional featurettes brought the public a behind-the-scenes look at Hollywood’s production process. Based on historical evidence, this article explores the changes in Hollywood promotions when studios broadcasted these featurettes on television to market theatrical films and contracted out promotional campaigns to boutique advertising agencies. The making-of form matured in the 1960s as featurettes helped solidify some enduring conventions about the portrayal of filmmaking. Ultimately, featurettes serve as important paratexts for understanding how Hollywood’s global production work was promoted during a time of industry transition. aking-of documentaries have long made Hollywood’s flm production pro- cess visible to the public. Before becoming a staple of DVD and Blu-ray spe- M cial features, early forms of making-ofs gave audiences a view of the inner workings of Hollywood flmmaking and movie companies. Shortly after its formation, 20th Century-Fox produced in 1936 a flmed studio tour that exhibited the company’s diferent departments on the studio lot, a key feature of Hollywood’s detailed division of labor. Even as studio-tour short subjects became less common because of the restructuring of studio operations after the 1948 antitrust Paramount Case, long-form trailers still conveyed behind-the-scenes information. In a trailer for The Ten Commandments (1956), director Cecil B. DeMille speaks from a library set and discusses the importance of foreign location shooting, recounting how he shot the flm in the actual Egyptian locales where Moses once walked (see Figure 1). -

Why Hollywood Isn't As Liberal As We Think and Why It Matters

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2019 Why Hollywood Isn't As Liberal As We Think nda Why It Matters Amanda Daily Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Daily, Amanda, "Why Hollywood Isn't As Liberal As We Think nda Why It Matters" (2019). CMC Senior Theses. 2230. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/2230 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Claremont McKenna College Why Hollywood Isn’t As Liberal As We Think And Why It Matters Submitted to Professor Jon Shields by Amanda Daily for Senior Thesis Fall 2018 and Spring 2019 April 29, 2019 2 3 Abstract Hollywood has long had a reputation as a liberal institution. Especially in 2019, it is viewed as a highly polarized sector of society sometimes hostile to those on the right side of the aisle. But just because the majority of those who work in Hollywood are liberal, that doesn’t necessarily mean our entertainment follows suit. I argue in my thesis that entertainment in Hollywood is far less partisan than people think it is and moreover, that our entertainment represents plenty of conservative themes and ideas. In doing so, I look at a combination of markets and artistic demands that restrain the politics of those in the entertainment industry and even create space for more conservative productions. Although normally art and markets are thought to be in tension with one another, in this case, they conspire to make our entertainment less one-sided politically. -

Visual Effects Society Names Acclaimed Filmmaker Martin Scorsese Recipient of the VES Lifetime Achievement Award

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Naomi Goldman, NLG Communications T: 424-293-2113 [email protected] Visual Effects Society Names Acclaimed Filmmaker Martin Scorsese Recipient of the VES Lifetime Achievement Award Los Angeles (September 19, 2019) – Today, the Visual Effects Society (VES), the industry’s professional global honorary society, named Martin Scorsese, Academy, DGA and Emmy Award winning director- producer-screenwriter, as the forthcoming recipient of the VES Lifetime Achievement Award in recognition of his valuable contributions to filmed entertainment. The award will be presented at the 18th Annual VES Awards on January 29, 2020 at the Beverly Hilton Hotel. The VES Lifetime Achievement Award, bestowed by the VES Board of Directors, recognizes an outstanding body of work that has significantly contributed to the art and/or science of the visual effects industry. VES will honor Scorsese for his consummate artistry, expansive storytelling and profound gift for blending iconic imagery and unforgettable narrative on an epic scale. Scorsese’s steadfast ability to harness craft and technology to bring his unique visions to life has resulted in exceptional narratives that have transfixed audiences and captivated millions. And as a champion of film history, his work to preserve the rich legacy of motion pictures is unparalleled. “Martin Scorsese is one of the most influential filmmakers in modern history and has made an indelible mark on filmed entertainment,” said Mike Chambers, VES Board Chair. “His work is a master class in storytelling, which has brought us some of the most memorable films of all time. His intuitive vision and fiercely innovative direction has given rise to a new era of storytelling and has made a profound impact on future generations of filmmakers. -

Godfather Part II by Michael Sragow “The a List: the National Society of Film Critics’ 100 Essential Films,” 2002

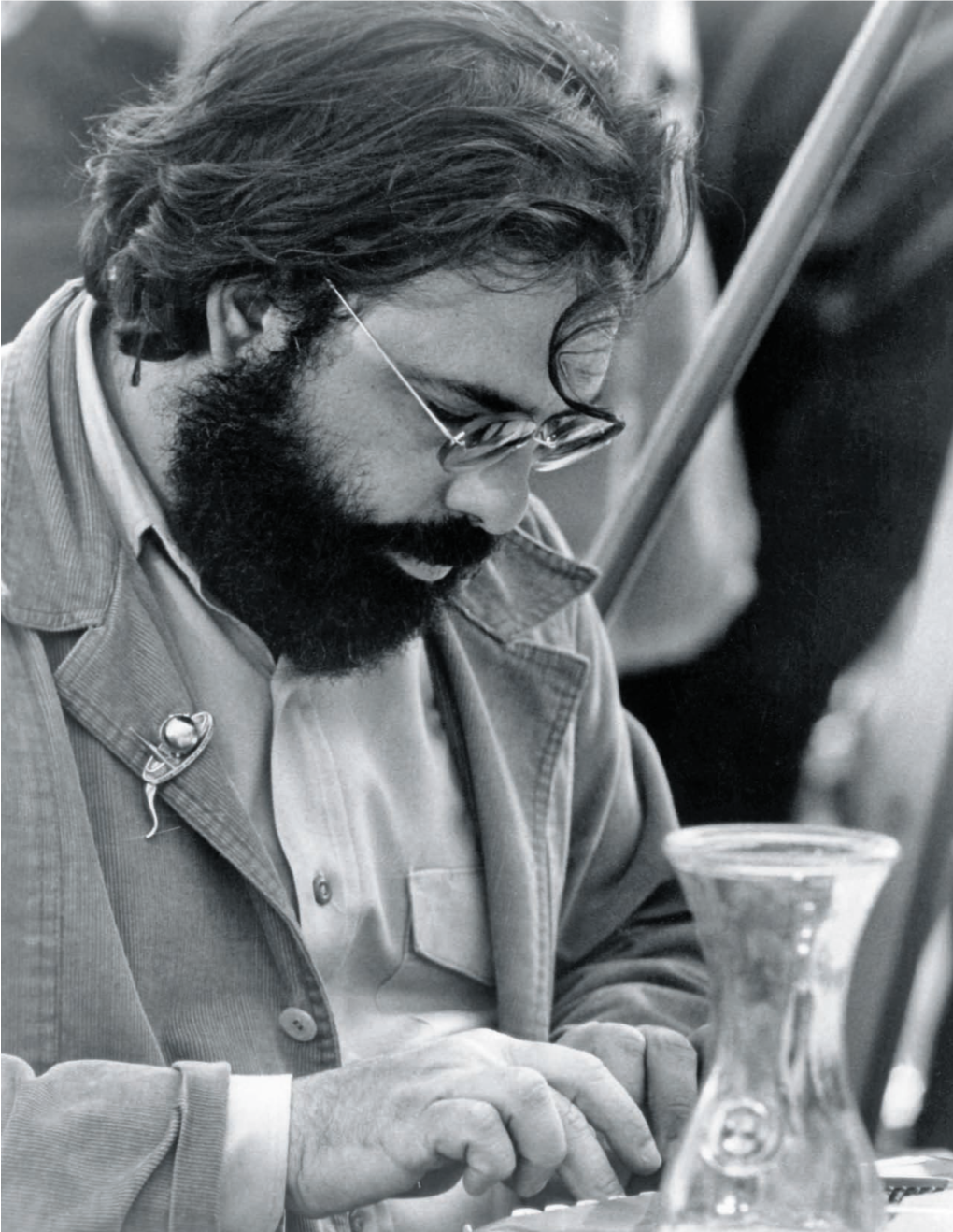

The Godfather and The Godfather Part II By Michael Sragow “The A List: The National Society of Film Critics’ 100 Essential Films,” 2002 Reprinted by permission of the author Although Francis Ford Coppola has often been depicted president.” — and loves to depict himself — as primarily an emotion- Kay re- al and intuitive director, “The Godfather” is a film filled sponds, with correct choices, painstakingly thought out and pas- “You know sionately carried through. Part of what made it a break- how naïve through as a crime move is that it’s about gangsters who you sound? make choices too and aren’t propelled simply by blood- Senators lust and greed. They’re battling for position in New York’s and presi- Five Families, circa 1945-1946. If Don Vito Corleone dents don’t (Marlon Brando) and his successor Michael (Al Pacino) have men come off looking better than all the others, it’s because killed.” In a they play the power game the cleverest and best — and line that Marlon Brando as Don Vito Corleone. the game is sordidly exciting. marked a Courtesy Library of Congress breakthrough For all the movie’s warmth, you could never confuse the for mainstream political awareness when the film premi- Corleones or their allies and competitors for fun-loving ered in 1972, Michael wearily answers, “Who’s being ethnic types. The first scene shows the Don exacting naïve, Kay?” deadly patronage, coercing an undertaker named Bonasera into vows of love and pledges of unmitigated But when Michael says his father’s way of doing things is loyalty in exchange for a feudal bond than can’t be bro- finished, he is being naïve. -

List of Restored Films

Restored Films by The Film Foundation Since 1996, the Hollywood Foreign Press Association has contributed over $4.5 million to film preservation. The following is a complete list of the 89 films restored/preserved through The Film Foundation with funding from the HFPA. Abraham Lincoln (1930, d. D.W. Griffith) Age of Consent, The (1932, d. Gregory La Cava) Almost a Lady (1926, d. E. Mason Hopper) America, America (1963, d. Elia Kazan) American Aristocracy (1916, d. Lloyd Ingraham) Aparjito [The Unvanquished] (1956, d. Satyajit Ray) Apur Sansar [The World of APU] (1959, d. Satyajit Ray) Arms and the Gringo (1914, d. Christy Carbanne) Ben Hur (1925, d. Fred Niblo) Bigamist, The (1953, d. Ida Lupino) Blackmail (1929, d. Alfred Hitchcock) – BFI Bonjour Tristesse (1958, d. Otto Preminger) Born in Flames (1983, d. Lizzie Borden) – Anthology Film Archives Born to Be Bad (1950, d. Nicholas Ray) Boy with the Green Hair, The (1948, d. Joseph Losey) Brandy in the Wilderness (1969, d. Stanton Kaye) Breaking Point, The (1950, d. Michael Curtiz) Broken Hearts of Broadway (1923, d. Irving Cummings) Brutto sogno di una sartina, Il [Alice’s Awful Dream] (1911) Charulata [The Lonely Wife] (1964, d. Satyajit Ray) Cheat, The (1915, d. Cecil B. deMille) Civilization (1916, dirs. Thomas Harper Ince, Raymond B. West, Reginald Barker) Conca D’oro, La [The Golden Shell of Palermo] (1910) Come Back To The Five and Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean (1982, d. Robert Altman) Corriere Dell’Imperatore, Il [The Emperor’s Message] (1910, d. Luigi Maggi) Death of a Salesman (1951, d. Laslo Benedek) Devi [The Godess] (1960, d. -

National Film Registry Titles Listed by Release Date

National Film Registry Titles 1989-2017: Listed by Year of Release Year Year Title Released Inducted Newark Athlete 1891 2010 Blacksmith Scene 1893 1995 Dickson Experimental Sound Film 1894-1895 2003 Edison Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze 1894 2015 The Kiss 1896 1999 Rip Van Winkle 1896 1995 Corbett-Fitzsimmons Title Fight 1897 2012 Demolishing and Building Up the Star Theatre 1901 2002 President McKinley Inauguration Footage 1901 2000 The Great Train Robbery 1903 1990 Life of an American Fireman 1903 2016 Westinghouse Works 1904 1904 1998 Interior New York Subway, 14th Street to 42nd Street 1905 2017 Dream of a Rarebit Fiend 1906 2015 San Francisco Earthquake and Fire, April 18, 1906 1906 2005 A Trip Down Market Street 1906 2010 A Corner in Wheat 1909 1994 Lady Helen’s Escapade 1909 2004 Princess Nicotine; or, The Smoke Fairy 1909 2003 Jeffries-Johnson World’s Championship Boxing Contest 1910 2005 White Fawn’s Devotion 1910 2008 Little Nemo 1911 2009 The Cry of the Children 1912 2011 A Cure for Pokeritis 1912 2011 From the Manger to the Cross 1912 1998 The Land Beyond the Sunset 1912 2000 Musketeers of Pig Alley 1912 2016 Bert Williams Lime Kiln Club Field Day 1913 2014 The Evidence of the Film 1913 2001 Matrimony’s Speed Limit 1913 2003 Preservation of the Sign Language 1913 2010 Traffic in Souls 1913 2006 The Bargain 1914 2010 The Exploits of Elaine 1914 1994 Gertie The Dinosaur 1914 1991 In the Land of the Head Hunters 1914 1999 Mabel’s Blunder 1914 2009 1 National Film Registry Titles 1989-2017: Listed by Year of Release Year Year