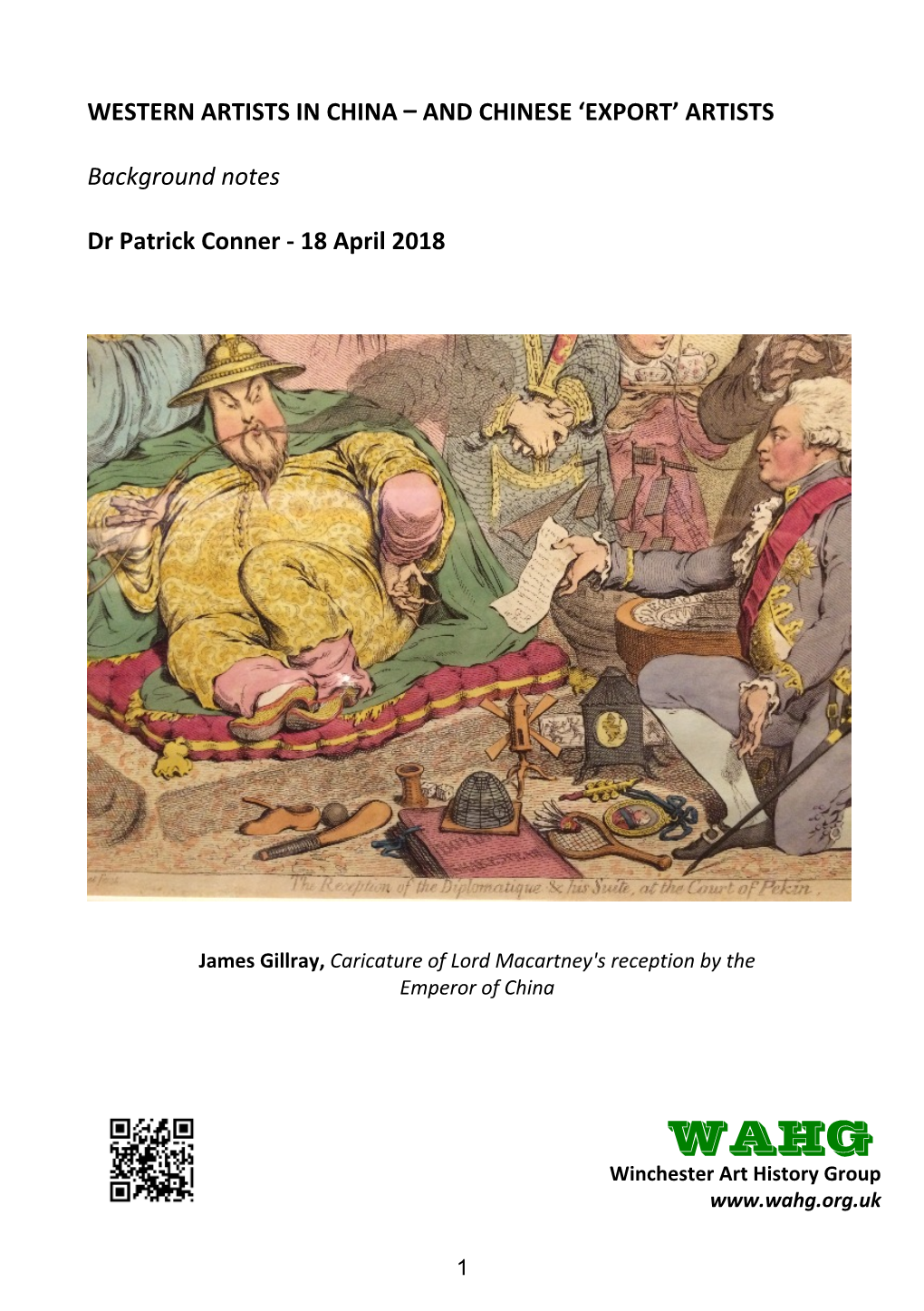

Western Artists in China and Chinese Export

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Houqua and His China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century

Global Positioning: Houqua and His China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Wong, John. 2012. Global Positioning: Houqua and His China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:9282867 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA © 2012 – John D. Wong All rights reserved. Professor Michael Szonyi John D. Wong Global Positioning: Houqua and his China Trade Partners in the Nineteenth Century Abstract This study unearths the lost world of early-nineteenth-century Canton. Known today as Guangzhou, this Chinese city witnessed the economic dynamism of global commerce until the demise of the Canton System in 1842. Records of its commercial vitality and global interactions faded only because we have allowed our image of old Canton to be clouded by China’s weakness beginning in the mid-1800s. By reviving this story of economic vibrancy, I restore the historical contingency at the juncture at which global commercial equilibrium unraveled with the collapse of the Canton system, and reshape our understanding of China’s subsequent economic experience. I explore this story of the China trade that helped shape the modern world through the lens of a single prominent merchant house and its leading figure, Wu Bingjian, known to the West by his trading name of Houqua. -

William Jardine (Merchant) from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

William Jardine (merchant) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For other people with the same name see "William Jardine" (disambiguation) William Jardine (24 February 1784 – 27 February 1843) was a Scottish physician and merchant. He co-founded the Hong Kong conglomerate Jardine, Matheson and Company. From 1841 to 1843, he was Member of Parliament for Ashburton as a Whig. Educated in medicine at the University of Edinburgh, Jardine obtained a diploma from the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh in 1802. In the same year, he became a surgeon's mate aboard the Brunswick of the East India Company, bound for India. Captured by the French and shipwrecked in 1805, he was repatriated and returned to the East India Company's service as ship's surgeon. In May 1817, he left medicine for commerce.[1] Jardine was a resident in China from 1820 to 1839. His early success in Engraving by Thomas Goff Lupton Canton as a commercial agent for opium merchants in India led to his admission in 1825 as a partner of Magniac & Co., and by 1826 he was controlling that firm's Canton operations. James Matheson joined him shortly after, and Magniac & Co. was reconstituted as Jardine, Matheson & Co in 1832. After Imperial Commissioner Lin Zexu confiscated 20,000 cases of British-owned opium in 1839, Jardine arrived in London in September, and pressed Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston for a forceful response.[1] Contents 1 Early life 2 Jardine, Matheson and Co. 3 Departure from China and breakdown of relations 4 War and the Chinese surrender Portrait by George Chinnery, 1820s 5 Death and legacy 6 Notes 7 See also 8 References 9 External links Early life Jardine, one of five children, was born in 1784 on a small farm near Lochmaben, Dumfriesshire, Scotland.[2] His father, Andrew Jardine, died when he was nine, leading the family in some economic difficulty. -

The Presence of the Past

THE PRESENCE OF 15 THE PAST Imagination and Affect in the Museu do Oriente, Portugal Elsa Peralta In 1983 UNESCO designated the Monastery of the Hieronymites and the Tower of Belém in Lisbon as World Heritage Sites. According to UNESCO’s website, the monastery “exemplifies Portuguese art at its best” and the Tower of Belém “is a reminder of the great maritime discoveries that laid the foundations of the mod ern world.”1 Less than 10 years after the formal end of the Portuguese colonial empire, UNESCO made use of the exemplar of Portuguese art to reaffirm the long‐used interpretive framework through which Portuguese imperial history has been read both nationally and internationally: Portugal was the country of the “Discoveries,” not a colonial center. Widely disseminated through schools, public discourses, and propaganda since the end of the nineteenth century, this interpretation of Portugal’s imperial history is strongly embedded in the coun try’s material culture. The naming of streets, bridges, schools, theaters, and mon uments after “heroes,” sites, or themes of the Discoveries operates to establish a forceful intimacy with the past, which is materially embedded in the very experi ence of the space itself. In addition, the public displays, exhibitions, and museums that address the topic – with objects that are often treated as art or antiques – unfailingly exalt the material and visual properties of the objects that testify to Portugal’s imperial deeds. I argue that this focus on materiality, together with an aesthetic lauding of historical objects, has contributed greatly to the resilience of the established view of Portugal’s imperial and colonial past, and made it resistant to modes of representation other than the nostalgic mode of historical grandeur and civilizing legacy. -

The Tombstones of the English East India Company Cemetery in Macao: a Linguistic Analysis

O'Regan, J. P. (2009). The tombstones of the English East India Company cemetery in Macao: a linguistic analysis. Markers XXVI. Journal of the Association of Gravestone Studies. 88-119. THE TOMBSTONES OF THE ENGLISH EAST INDIA COMPANY CEMETERY AT MACAO: A LINGUISTIC ANALYSIS JOHN P. O’REGAN1 It was Macao’s privilege to save their names from oblivion, and looking at these epitaphs you realize that “They, being dead, yet speak”. J. M. Braga (1940)1 Introduction In a quiet corner of the former Catholic Portuguese colony of Macao, China, away from the bustle and hum of the surrounding streets, there is to be found a small nineteenth century burial ground for Protestants – British and American in the main, but also including French, German, Danish, Dutch, Swedish and Armenian graves. The ground is entered via a narrow gate off the Praça Luis de Camões (Camoens Square), above which is a white tablet bearing the legend: ‘Protestant Church and Old Cemetery [East India Company 1814]’. The date is in fact erroneous, as the burial ground did not open until 1821, and the land was only purchased in the same year.2 Here beneath shaded canopies of bauhinia and frangipani lie 164 men, women and children each of whom died in the service of their nation in a foreign land, either as soldiers, merchants, sailors, medics, diplomats, civil servants, entrepreneurs, missionaries, wives, mothers or innocents. The maladies of which the cemetery’s residents died were numerous, and all too typical of life in the tropics. Their death certificates, and in some cases their gravestones, indicate malaria, cholera, typhus, dysentery, falls from aloft, drowning, death in battle, suicide and murder. -

Canton & Hong Kong

Rise & Fall of the Canton Trade System Lesson 02 Mini-Database: “Canton & Hong Kong” Part One: Canton “Portrait of the Fou-yen of Canton at an English dinner,” January 8, 1794 by William Alexander. British Museum [cwPT_1796_bm_AN166465001c] “The Hong Merchant Mouqua,” ca. 1840s by Lam Qua. Peabody Essex Museum [cwPT_1840s_ct79_Mouqua] "Howqua" by George Chinnery, 1830 [cwPT_1830_howqua] Metropolitan Museum of Art Porcelain punch bowl, ca. 1785 Peabody Essex Museum [cwO_1785c_E75076] “Canton with the Foreign Factories,” ca. 1800 Unknown Chinese artist. Peabody Essex Museum [cwC_1800c_E79708] “A British Map of Canton, 1840,” by W. Bramston. Hong Kong Museum of Art [cwC_1840_AH64115_Map] “Foreign Factory Site at Canton,” ca. 1805 Reverse-glass painting, unknown Chinese artist. Peabody Essex Museum [cwC_1805_E78680] “A View of Canton from the Foreign Factories,” ca. 1825 Unknown artist. Hong Kong Museum of Art [cwC_1825_AH928] Porcelain punch bowl, ca. 1785 Peabody Essex Museum [cwO_1785c_E75076] “New China Street in Canton,” 1836–1837 by Lauvergne; lithograph by Bichebois. National Library of Australia [cwC_1836-37_AN10395029] “The Factories of Canton” 1825–1835 Attributed to Lam Qua, oil on canvas. Peabody Essex Museum [cwC_1825-35_M3793] “The American Garden,” 1844–45 Unknown Chinese artist. Peabody Essex Museum [cwC_1844-45_E82881_Garden] Reverse-glass painting, ca. 1760–80 Unknown Chinese Artist. Victoria & Albert, Guangzhou, China [cwPT_1760-80_2006AV3115_VA] Rise & Fall of the Canton Trade System Lesson 02 Mini-Database: “Canton & Hong Kong” Part Two: Hong Kong “Waterfall at Aberdeen,” 1817 by William Harvell. Hong Kong Museum of Art [cwHK_1817_AH64362] “View of Hong Kong From East Market, April 7, 1853,” by William Heine. Commodore Matthew Perry's Japan Expedition [cwHK_1853_Heine_bx] “View of Victoria Town, Island of Hong Kong, 1850,” by B. -

Record of the Old Protestant Cemetery in Macau

OLD PROTESTANT CEMETERY IN MACAU Cemetery opened 1821 Cemetery closed in 1858 The Old Protestant Cemetery close to the Casa Garden was established by the British East India Company in 1821 in Macau - in response to a lack of burial sites for Protestants in the Roman Catholic Portuguese Colony Macau was considered by the Portuguese to be sacred Roman Catholic ground and the authorities barred the burial of Protestants within its city walls whilst on the other side of the barrier gate the Chinese were equally as intolerant of the burial of foreigners in its soil This left the Protestant community of British, American and Northern European traders with the only option of a secret night-time burial in the land between the city walls and the barrier gate and the risk of confrontation with Chinese should they be discovered or worse - desecration of the grave once they had gone. The matter was finally resolved in 1821 after the death of Robert Morrison's wife Mary when the local committee of the East India Company voted to purchase a plot of land and resolve its legal status with the Portuguese such that the burial of Protestants would be permitted there Later the East India Company allowed burial of all foreigners and several graves were moved from other locations outside the city walls into the cemetery with people being reinterred from other burial places in the Macao Hillside thus explaining why some graves are dated before the Cemetery founding in 1821 Nationals of Britain, the United States of America, Holland, Denmark, Sweden and Germany -

Howqua's Garden in Honam, China

This is a repository copy of Uncovering the garden of the richest man on earth in nineteenth-century Canton: Howqua's garden in Honam, China. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/114939/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Richard, J.C. (2015) Uncovering the garden of the richest man on earth in nineteenth-century Canton: Howqua's garden in Honam, China. Garden History, 43 (2). pp. 168-181. ISSN 0307-1243 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Uncovering the garden of the richest man on earth in nineteenth century Guangzhou s garden in Henan, China. (owqua Abstract Gardens in Lingnan, particularly those located in and around Guangzhou (Canton), were among the first Chinese gardens to be visited by Westerners, as until the Opium Wars, movements of foreigners were restricted to the city of Guangzhou, with the exception of a few missionaries who were able to enter Beijing. -

The Chinese Name for “Australia” Becomes “Chinese”

The Chinese name for Australia1 David L B Jupp Final Penultimate Version, June 2013. Figure 1 The Australian Pavilion at the Shanghai World Expo of 2010. Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION – WHAT’S IN A NAME? ............................................................................ 2 2 AN EARLY CHINESE MAP OF AUSTRALIA ........................................................................ 3 3 WHO DISCOVERED THE CHINESE NAME FOR AUSTRALIA? ...................................... 7 4 “AUSTRALIA” IN THE WORLD’S MAPS .............................................................................. 9 5 OPENING CHINA TO COMMERCE AND CHRISTIANITY ............................................. 15 6 THE PROVISION OF USEFUL GEOGRAPHIC KNOWLEDGE IN CHINESE............... 19 7 THE CHINESE MAGAZINE AND THE NAME FOR AUSTRALIA IN CHINESE .......... 22 7.1 THE “CHINESE MAGAZINES” .................................................................................................... 22 7.2 WALTER MEDHURST’S NAME FOR AUSTRALIA IN CHINESE ...................................................... 26 8 LIN ZEXU AND THE FORCED OPENING OF CHINA ...................................................... 31 9 THE STORIES OF WEI YUAN, LIANG TINGNAN AND XU JIYU .................................. 37 9.1 WEI YUAN COLLECTS ALL OF THE INFORMATION ...................................................................... 37 9.2 LIANG TINGNAN DISCUSSES THE NAME FOR AUSTRALIA .......................................................... 42 9.3 XU JIYU PUTS AODALIYA ON THE MAP ..................................................................................... -

Published in Conjunction with 澳門特別行政區政府文化局 INSTITUTO CULTURAL Do Governo Da R.A.E. De Macau

Published in conjunction with ʼʝѫ֚ܧਂܧऋПϷپዌ INSTITUTO CULTURAL do Governo da R.A.E. de Macau Hong Kong University Press 14/F Hing Wai Centre 7 Tin Wan Praya Road Aberdeen Hong Kong © Jeremy Tambling and Louis Lo 2009 ISBN 978-962-209-937-1 Hardback ISBN 978-962-209-938-8 Paperback All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Secure On-line Ordering ——————————— http://www.hkupress.org British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue copy for this book is available from the British Library. Printed and bound by United League Graphic & Binding Co. Ltd. in Hong Kong, China Table of Contents List of Illustrations vi Chapter 7 118 Walling the City Preface ix Chapter 8 136 Chapter 1 2 Macao’s Chinese Architecture Learning from Macao: An Introduction Chapter 9 158 Chapter 2 20 Colonialism and Modernity Seven Libraries Chapter 10 180 Chapter 3 38 Camões and the Casa Garden Igreja e Seminário São José (St Joseph’s Seminary and Church) Chapter 11 198 Is Postmodern Macao’s Architecture Chapter 4 60 Baroque? Igreja de São Domingos (Church of St Dominic) Chapter 12 224 Death in Macao Chapter 5 80 Ruínas de São Paulo Notes 234 (Ruins of St Paul’s) Glossary of Terms 249 Chapter 6 98 Neo-Classicism Index of Macao Places 254 General Index 256 Walking Macao, Reading the Baroque Illustrations Chapter 1 20. -

History of Photography in China, 1842-1860, by Terry Bennett, Published

Terry Bennett, History of Photography in China, 1842-1860, London, Bernard Quaritch Ltd, 2009, pp. 242, 150 plus illustrations. Valery Garrett Much has been written on Western and Chinese painters in China in the mid 19th century. But with the exception of Felix Beato and John Thomson, subjects of recent exhibitions, very little is said about photographers producing images of that exotic country visited by few. Now Terry Bennett, an international authority on historical photographs and author of books on photography in Japan and Korea, has put together an impressive volume on photography in China, 1842-1860. This first comprehensive history of the earliest years of photography, from the end of the first Opium War to the end of the Second China War, combines previously unpublished research with over 150 photographs, many of which are attributed and published here for the first time. The author sheds new light on the unique value of these photographs and the book reads smoothly and well. Previous books of photographs in China have concentrated on the subject matter. Here Bennett focuses on the photographers and says, “…some nineteenth- century photographs are truly artistic. In those cases, should we not want to know the name of the artist – and something of his life and history? One of the aims of this book has, therefore, been to try wherever possible to identify the photographer. Beyond that I have also tried to discover something about the lives and personalities of the photographers.” To achieve this, the topics for each of the chapters are organised into lists of photographers with biographical details both brief and extensive when required. -

Martyn Gregory

REVEALING THE EAST • Cover illustration: no. 50 (detail) 2 REVEALING THE EAST Historical pictures by Chinese and Western artists 1750-1950 2 REVEALING THE EAST Historical pictures by Chinese and Western artists 1750-1950 MARTYN GREGORY CATALOGUE 91 2013-14 Martyn Gregory Gallery, 34 Bury Street, St. James’s, London SW1Y 6AU, UK tel (44) 20 7839 3731 fax (44) 20 7930 0812 email [email protected] www.martyngregory.com 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Our thanks are due to the following individuals who have generously assisted in the preparation of catalogue entries: Jeremy Fogg Susan Chen Hardy Andrew Lo Ken Phillips Eric Politzer Geoffrey Roome Roy Sit Kai Sin Paul Van Dyke Ming Wilson Frances Wilson 4 CONTENTS page Works by European and other artists 7 Works by Chinese artists 34 Works related to Burma (Myanmar) 81 5 6 PAINTINGS BY EUROPEAN AND OTHER ARTISTS 2. J. Barlow, 1771 1. Thomas Allom (1804-1872) A prospect of a Chinese village at the Island of Macao ‘Close of the attack on Shapoo, - the Suburbs on fire’ Pen and ink and grey wash, 5 ½ x 8 ins Pencil and sepia wash, 5 x 7 ½ ins Signed and dated ‘I Barlow 1771’, and inscribed as title Engraved by H. Adlard and published with the above title in George N. Wright, China, in a series of views…, 4 vols., 1843, vol. The author of this remarkably early drawing of Macau was III, opp. p.49 probably the ‘Mr Barlow’ who is recorded in the East India Company’s letter books: on 4 August 1771 he was given permission Thomas Allom’s detailed watercolour would probably have been by the Governor and Council of Fort St George, Madras (Chennai) redrawn from an eye-witness sketch supplied to him by one of to sail from there to Macau on the Company ship Horsendon (letter the officer-artists involved in the First Opium War, such as Lt received 22 Sep. -

George Chinnery Comes Home

The Newsletter | No.58 | Autumn/Winter 2011 48 | The Portrait George Chinnery comes home George Chinnery enjoyed a double career in the Far East. The first phase was in India, where he rose to become the principal artist of the Raj, a hookah-smoking ‘old hand’ with an Indian mistress and a huge appetite for curry and rice. ‘Chinnery himself could not hit off a likeness better’, exclaims the Colonel back from India, as he admires a portrait in Thackeray’s Newcomes. Patrick Conner 1. The Flamboyant Mr Chinnery (1774-1852) on the beach (figure 1). These sketches are perhaps the his watercolours of palanquin bearers in Madras, ruined tombs 1: The Praya Grande – an English Artist in India and China most appealing element of his oeuvre. They reveal an almost in Bengali villages, and junks at anchor on a calm evening on Macao from the north, Loan exhibition at Asia House, London, obsessive determination to perfect his drawing of human the China coast. His early years in England and Ireland are with further sketches from 4 November 2011 to 21 January 2012 figures engaged in their daily activities. These are not the covered in summary fashion, but we do see a charming small Pencil, pen and ink, work of an idle voluptuary, but of an artist dedicated to his portrait from that time: his young wife Marianne in 1800, on two joined pieces of paper, 27.6 x 48 cm AT THE agE OF 51, when he might have been expected to ideal, which he pursued with a vigour seldom seen in his earlier looking out demurely from beneath a luxuriant mass of hair Inscribed and dated in retire to Britain, Chinnery moved in the opposite direction.