The Works of Henrik Ibsen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE CHEKHOV DREAMS a Play by John Mckinney Copyright © 2014

THE CHEKHOV DREAMS A play by John McKinney Copyright © 2014 by John McKinney 67 East 11St. Apt. #708 New York, NY 10003 (212) 598-9970 [email protected] ii CHARACTERS JEREMY Mid-30’s, affable, well-read, reclusive, a wounded soul. KATE Mid-30’s, beautiful, sophisticated, perceptive, deceased. CHRISSY Early 20’s, cute, upbeat, eager, passionate. EDDIE Late 30’s, jaded, decadent, addicted to just about everything. CHEKHOV Mid 40’s, wise, eccentric, crotchety, deceased. SETTING Time: The present. Place: New York City, various locations; A lake, various times and seasons. Author’s notes: This play was written as a dark romantic comedy, accent on the comedy. As such, the default tempo for the play should be brisk and lively, pausing or stopping only as necessary to reflect the deeper, more serious moments. Scene transitions should occur as smoothly as possible with a minimum of set and prop handling to ensure that the story keeps moving apace. In essence the play should avoid the trap of over-indulging in the darker currents of the story and becoming labored or ponderous. As this play explores two alternating states of mind – dreams and reality – it is intended that the design elements establish a distinctive motif for each. For example, there might be a magical, sparkling quality to the lighting to represent the water reflecting off of the lake in the dream scenes, while the real life apartment scenes might have a grittier, more somber feel especially as most of these scenes occur at night. Similarly, the dream scenes might be accompanied by a recurring ethereal theme, or “dreamscape,” which would shift in tone from light and magical to something more ominous, reflecting the main character’s psychological journey. -

• Principals Off Er Alternative to Loans Scheme

IRlBOT RICE GRLLERY a. BRQ~ University of Edinburgh, Old College THE South Bridge, Edinburgh EH8 9YL Tel: 031-667 1011 ext 4308 STATIONERS 24 Feb-24 March WE'RE BETTER FRANCES WALKER Tiree Works Tues·Sat 10 am·5 pm Admission Free Subsidised by the Scottish Ans Council Glasgow Herald Studen_t' Newspaper of the l'. ear thursday, february 15, 12 substance: JUNO A.ND •20 page supplement, THE PAYCOCK: Lloyd Cole interview .Civil War tragedy . VALENTINES at the .and compe~tion insi~ P.13 Lyceum p.10 Graduate Tax proposed • Principals offer alternative to loans scheme by Mark Campanile Means tested parental con He said that the CVCP administrative arrangements for Mr MacGregor also stated that tributions would be abolished, accepted that, in principle, stu loans and is making good prog administrative costs would be pro ress." hibitive, although the CVCP UNIVERSITY VICE Chan and the money borrowed would dents should pay something be repayed through income tax or towards their own education, but "The department will of course claim their plan would be cheaper cellors ancf Principals have national insurance contributions. that they believed that the current . be meeting the representatives of to implement than the combined announced details of a A spokesman for the CVCP, loans proposals were unfair, the universities, polytechnics, and running costs for grants and loans. graduate tax scheme which · Dr Ted Neild, told Student that administratively complicated, and colleges in due course to discuss NUS President Maeve Sher-. they want the government to the proposals meant that flawed because they still involved their role in certifying student lock has denounced the new prop consider as an alternative to graduates who had an income at a parental contributions, which are eligibility for loans." osals as "loans by any other student loans. -

The Girls at Mount Morris

The Girls at Mount Morris By Amanda Minnie Douglas The Girls At Mt. Morris CHAPTER I LOOKING THE FUTURE IN THE FACE Lilian Boyd entered the small, rather shabby room, neat, though everything was well worn. Her mother sat by a little work table busy with some muslin sewing and she looked up with a weary smile. Lilian laid a five-dollar bill on the table. “Madame Lupton sails on Saturday,” she said. “Oh how splendid it must be to go to Paris! Mrs. Cairns is to finish up; there is only a little to do, but Madame said everything you did was so neat, so well finished that she should be very glad to have you by the first of October.” The mother sighed. “Meanwhile there is almost two months to provide for, and I had to break in the last hundred dollars to pay the rent. Oh Lilian! I hardly know which way to turn. I am not strong any more, I have made every effort to—” and her voice broke, “but I am afraid you will have to give up school.” She buried her face in her hands and sobbed. “Oh, mother, don‟t! don‟t!” the girl implored. “I suppose it was selfish of me to think of such a thing and you couldn‟t go through two years more. You are not as well as you were a year ago. I‟ll see Sally Meeks tonight and take the place in the factory. I only have to give two weeks and then begin on five dollars a week. -

Kappale Artisti

14.7.2020 Suomen suosituin karaokepalvelu ammattikäyttöön Kappale Artisti #1 Nelly #1 Crush Garbage #NAME Ednita Nazario #Selˆe The Chainsmokers #thatPOWER Will.i.am Feat Justin Bieber #thatPOWER Will.i.am Feat. Justin Bieber (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderˆnger (Barry) Islands In The Stream Comic Relief (Call Me) Number One The Tremeloes (Can't Start) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue (Doo Wop) That Thing Lauren Hill (Every Time I Turn Around) Back In Love Again LTD (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Brandy (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Bryan Adams (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song B. J. Thomas (How Does It Feel To Be) On Top Of The W England United (I Am Not A) Robot Marina & The Diamonds (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction The Rolling Stones (I Could Only) Whisper Your Name Harry Connick, Jr (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (If Paradise Is) Half As Nice Amen Corner (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Shania Twain (I'll Never Be) Maria Magdalena Sandra (It Looks Like) I'll Never Fall In Love Again Tom Jones (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley-Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life (Duet) Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (Just Like) Romeo And Juliet The Re˜ections (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon (Marie's The Name) Of His Latest Flame Elvis Presley (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran (Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake Your Booty KC And The Sunshine Band (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding (Theme From) New York, New York Frank Sinatra (They Long To Be) Close To You Carpenters (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets (Where Do I Begin) Love Story Andy Williams (You Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears (You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party!) The Beastie Boys 1+1 (One Plus One) Beyonce 1000 Coeurs Debout Star Academie 2009 1000 Miles H.E.A.T. -

A DOLL's HOUSE by Henrik Ibsen Translated by William Archer

www.TaleBooks.com A DOLL'S HOUSE by Henrik Ibsen translated by William Archer INTRODUCTION INTRODUCTION by William Archer ON June 27, 1879, Ibsen wrote from Rome to Marcus Gronvold: "It is now rather hot in Rome, so in about a week we are going to Amalfi, which, being close to the sea, is cooler, and offers opportunity for bathing. I intend to complete there a new dramatic work on which I am now engaged." From Amalfi, on September 20, he wrote to John Paulsen: "A new dramatic work, which I have just completed, has occupied so much of my time during these last months that I have had absolutely none to spare for answering letters." This "new dramatic work" was Et Dukkehjem, which was published in Copenhagen, December 4, 1879. Dr. George Brandes has given some account of the episode in real life which suggested to Ibsen the plot of this play; but the real Nora, it appears, committed forgery, not to save her husband's life, but to redecorate her house. The impulse received from this incident must have been trifling. It is much more to the purpose to remember that the character and situation of Nora had been clearly foreshadowed, ten years earlier, in the figure of Selma in The League of Youth. Of A Doll's House we find in the Literary Remains a first brief memorandum, a fairly detailed scenario, a complete draft, in quite actable form, and a few detached fragments of dialogue. These documents put out of court a theory of my own * that Ibsen originally intended to give the play a "happy ending," and that the relation between Krogstad and Mrs. -

The Monarch Edition 19.1 October 2009 (Pdf)

OPINIONS Opposing Viewpoints: In State vs. Out of State Colleges CALIFORNIA, HERE WE COME THERE’SA WORLD OUT THERE By Kyle Kubo state is basically a big bacon-shaped college By Sneha Singh University in Illinois which would reduce Staff Writer town: the weather is perpetually balmy, there Staff Writer the amount of time in school, as well as save is a substantial amount of terrain for skiing of money on tuition. For many a harried high school senior, and snowboarding, and in the areas sur- Most people choose to go to college Another plus to choosing a college the mere mention of college evokes an rounding the major colleges you can’t throw simply because a higher-education degree outside your home state would be the slight intoxicating wanderlust, an almost primal a rock without hitting three Taco Bells, two usually results in better job opportunities. leeway on SAT scores and cumulative urge to fl y from the nest, take to the skies, movie theaters, and a minor celebrity. The While some high school graduates choose GPA. Because all colleges want diverse and defecate on the parked cars of home- entire left side is a beach, for goodness’ sake! to stay in state for college due to the seem- representation, many schools would rather town familiarity and parental oppression. Students living in Solitude, Indiana and Or- ingly obvious closeness to home and the take someone from a different part of the College is perceived as a magical land dinary, Kentucky (yes, real places) can be savings on cost, choosing a college out of country as opposed to someone local with where siblings are disowned, cake can be excused if they feel the need to explore past state is far more benefi cial because students the exact same qualifi cations. -

Ulkomaiset Esittäjät

Ulkomaiset esittäjät Artisti Kappale *NSYNC Bye Bye Bye 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 2 Pac Featuring Dr. Dre California Love 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Changes 2Pac Dear Mama 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 4 Non Blondes What's Up 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Feat. Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5ive We Will Rock You A Great Big World & Christina Aguilera Say Something A Great Big World Feat. Christina Say Something Aguilera A Little Night Music (Broadway Send In The Clowns Version) A1 Like A Rose A1 Take On Me Aashiqui 2 Tum Hi Ho ABBA Angels Eyes Abba Chiquitita Abba Dancing Queen ABBA Does Your Mother Know ABBA Fernando ABBA Gimme Gimme Gimme ABBA Happy New Year ABBA Hasta Manana ABBA Honey Honey ABBA I Do I Do I Do I Do I Do Artisti Kappale ABBA I Have A Dream ABBA Knowing Me Knowing You Abba Knowing Me, Knowing You ABBA Lay All Your Love On Me ABBA Mamma Mia ABBA Money Money Money ABBA One Of Us ABBA Ring Ring ABBA S.O.S ABBA S.O.S. ABBA Summer Night City ABBA Super Trouper ABBA Take A Chance On Me ABBA Thank You For The Music ABBA The Day Before You Came Abba The Name Of The Game Abba The Winner Takes It All Abba Waterloo ABBA Voulez-Vous ABC The Look Of Love AC DC Back In Black AC DC Highway To Hell AC DC Thunderstruck AC/DC Back In Black AC/DC Big Balls AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap AC/DC For Those About -

Second Quarter 2015 the East Asia Issue

Samurai Shodown Anthology The classic fighting game compilation reviewed, PAGE 17 10 things to know about the beloved series, PAGE 20 YEAR 08, NO. 30 WWW.GAMINGINSURRECTION.COM Second Quarter 2015 the east asia issue GI goes eastward for games, music, anime and more From the editor his is a special issue of Gaming Insurrection. We usually don’t miss deadlines and we don’t talk about T what’s going in the world outside of gaming in GI. But, re- cently, we experienced a sorrowful and painful loss. Gloria Nicholson Hicks, better known as GI Mama, passed away March 9. Gloria, my mother, was the lifeblood of GI and one of my Special earliest supporters when I began the idea that is Gaming Insurrec- tion. She was there, providing our first home, equipment and her services as a copy editor for the first three issues. She also helped with coallating the first issues because we had paper distribution then with local video game store Software Seconds. I greatly miss my mom, who was more than just a supporter and mom; she was my best friend and my source of strength when I didn’t think I’d make a dead- line, or ran into other obstacles in the production of something that I love to do. It is because of her death that we have been behind in the production of issues. And honestly, I didn’t think I’d even continue GI after her death. But, I knew she’d want me to continue doing something that brought me joy and gave me purpose, and so that’s what we’re going to do. -

Faith Hill I Ain't Gonna Take It Anymore Angie Stone I Ain't Hearin

Faith Hill I Ain't Gonna Take it Anymore Angie Stone I Ain't Hearin' U Webb Pierce I Ain't Never Shania Twain I Ain't No Quitter Carolina Rain I Ain't Scared Lynyrd Skynyrd I Ain't The One Gil Grand I Already Fell [Karaoke] Avril Lavigne I Always Get What I Want [Karaoke] Cyndi Thompson I Always Like That Best Mary J. Blige I Am Soggy Bottom Boys I Am A Man of Constant Sorrow Simon and Garfunkel I Am A Rock Ricky Van Shelton I Am A Simple Man Reba McEntire I Am A Survivor Neil Diamond I Am I Said Blenders I Am In Love With The Mcdonald's Girl [Karaoke] Cassadee Pope I Am Invincible Alice Cooper I Am Made of You Kenny Loggins I Am Not Hiding [Karaoke] India Arie I Am Not My Hair Brooks and dunn I Am that Man Halestorm I am The Fire Beatles I Am The Walrus Dusty Drake I Am The Working Man Alisha's Attic I Am, I Feel [Karaoke] Blessed Union of Souls I Believe Diamond Rio I Believe Fantasia I Believe R. Kelly I Believe I Can Fly Darkness I Believe In a Thing Called Love Greg Lake I Believe In Father Christmas Kenny Rogers & Dolly Parton I Believe In Santa Clause Don Williams I Believe In You Whitney Houston I Believe In You And Me George Strait I Believe You Lenny Kravitz I Belong To You Rome I Belong To you Arctic Monkeys I Bet You Look Good On The Dancefloor [Karaoke] Erika Jo I Break Things Chris Cagle I Breath In, I Breath Out natasha Bedingfield I Bruise Easily Beatles I Call Your Name Dan Hartman I Can Dream About You Manchester Orchestra I Can Feel A Hot One Beach Boys I Can Hear Music Hairspray I Can Hear The Bells Dixie Chicks I Can -

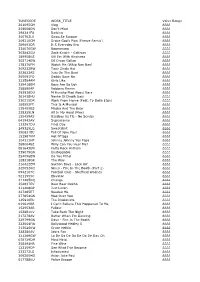

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261095CM

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261095CM Vlog ££££ 259008DN Don't Mind ££££ 298241FU Barking ££££ 300703LV Swag Se Swagat ££££ 309210CM Drake God's Plan (Freeze Remix) ££££ 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 234070GW Boomerang ££££ 302842GU Zack Knight - Galtiyan ££££ 189958KS Kill Em With Kindness ££££ 302714EW Dil Diyan Gallan ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 309232BW Tiger Zinda Hai ££££ 253823AS Juju On The Beat ££££ 265091FQ Daddy Says No ££££ 232584AM Girls Like ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 258890AP Robbery Remix ££££ 292938DU M Huncho Mad About Bars ££££ 261438HU Nashe Si Chadh Gayi ££££ 230215DR Work From Home (Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign) ££££ 188552FT This Is A Musical ££££ 135455BS Masha And The Bear ££££ 238329LN All In My Head (Flex) ££££ 155459AS Bassboy Vs Tlc - No Scrubs ££££ 041942AV Supernanny ££££ 133267DU Final Day ££££ 249325LQ Sweatshirt ££££ 290631EU Fall Of Jake Paul ££££ 153987KM Hot N*Gga ££££ 304111HP Johnny Johnny Yes Papa ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 081643EN Party Rock Anthem ££££ 239079GN Unstoppable ££££ 254096EW Do You Mind ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 216422EM Section Boyz - Lock Arf ££££ 325052KQ Nines - Fire In The Booth (Part 2) ££££ 0942107C Football Club - Sheffield Wednes ££££ 5211555C Elevator ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 254637EV Baar Baar Dekho ££££ 311408GP Just Listen ££££ 227485ET Needed Me ££££ 277854GN Mad Over You ££££ 125910EU The Illusionists ££££ 019619BR I Can't Believe This Happened To Me ££££ 152953AR Fallout ££££ 153881KV Take Back The Night ££££ 217278AV Better When -

Kappale Artisti

2.12.2020 Suomen suosituin karaokepalvelu ammattikäyttöön Kappale Artisti #1 Nelly #1 Crush Garbage #NAME Ednita Nazario #Sele The Chainsmokers #thatPOWER Will.i.am Feat Justin Bieber #thatPOWER Will.i.am Feat. Justin Bieber (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powdernger (Barry) Islands In The Stream Comic Relief (Call Me) Number One The Tremeloes (Doo Wop) That Thing Lauren Hill (Every Time I Turn Around) Back In Love Again LTD (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Brandy (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Bryan Adams (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song B. J. Thomas (How Does It Feel To Be) On Top Of The World England United (I Am Not A) Robot Marina & The Diamonds (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction The Rolling Stones (I Could Only) Whisper Your Name Harry Connick, Jr (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (If Paradise Is) Half As Nice Amen Corner (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Shania Twain (I'll Never Be) Maria Magdalena Sandra (It Looks Like) I'll Never Fall In Love Again Tom Jones (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley-Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life (Duet) Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (Just Like) Romeo And Juliet The Reections (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon (Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear Elvis Presley (Marie's The Name) Of His Latest Flame Elvis Presley (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran (Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake Your Booty KC And The Sunshine Band (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding (Theme From) New York, New York Frank Sinatra (They Long To Be) Close To You Carpenters (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets (Where Do I Begin) Love Story Andy Williams (You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party!) The Beastie Boys (You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman Aretha Franklin 1+1 (One Plus One) Beyonce 1000 Coeurs Debout Star Academie 2009 1000 Miles H.E.A.T. -

Olive Resume7.16.2013

olive makeup artistry’s resume local 706 commercial/television roster Job:!!!!!Type:!!!Director/Photog:!Position: GMC!!!!!Commercial!!Malcolm Venville!Key Makeup/Hair Playboy!! ! ! ! Editorial!!Gavin Bond!!Key Makeup/Hair/Sp.fx--Patton Oswalt irobot!!!!!Commercial!!Malcolm Venville!Key Makeup/Hair Danimals!!!!Commercial!!Eddy Chu!!Key Makeup Intel!!!!!Commercial!!Chris Hewitt!!Key Makeup/Hair Carnation!!!!Commercial/Ad!! Nick Piper/Dana Tynan!Key Makeup/Hair Atoms for Peace!!!Music Video!!Andy Huang!!Key Sp.fx for Thom Yorke Luvs!!!!!Commercial!!Brian Billow!!Key Makeup/Hair Ruffles!!!!!Commercial!!Jorge Colon!!Key Makeup/Hair Mazca 3!!!!Commercial!!the Cronenweths!Key Makeup/Hair Hyundai!!!!Commercial!!Ko, HanKi!!Key Makeup/Hair Rock and Roll Wonderland!!Special Project!!Bjorn Tagemose!Key Makeup/Hair/Sp.fx--Henry Rollins Comcast!!!!Commercial!!Omri Cohen!!Key Makeup/Hair Allstate!! ! ! ! Commercial!!Brian Billow!!Key Makeup/Hair Dawn!!!!!Commercial!!Nick Piper!!Key Makeup/Hair Rocksmith!!!!Commercial!!Dave Moodie!!Key Makeup/Hair Xbox!!!!!Commercial!!Jon Berkowitz!!Key Makeup/Hair Cal of Duty!!!!Commercial!!Mark Romanek!!Key Makeup/Hair/Sp.fx Golf.now!!!!Commercial!!Kim Nguyen!!Key Makeup/Hair New Era!!!!Commercial!!Corey Adams!!Key Makeup/Hair Domyos!!!!Commercial/Ad!! Stephanie Di Giusto!Key Makeup Aldo!!!!!Commercial!!Aaron Platt!!Key Makeup At&t!!!!!Commercial!!Brian Billow!!Key Makeup/Hair Charter!! ! ! ! Commercial!!Geordie Stephens!Key Makeup/Hair Hyundai!!!!Commercial!!Ko, HanGi!!Key Makeup/Hair Apple!!!!!Commercial!!anonymous!!Key Makeup/Hair Right Guard!!!!Commercial!!Nick Piper!!Key Makeup/Hair Teenwolf !!!!Ad Campaign!!Gavin Bond!!Key Makeup/Hair/Sp.fx. Walmart!!!!Commercial!!Matthew Herath!! Key Makeup/Hair SyFy Helix!!!!Promo!!!Jose Gomez!!Key Makeup/Hair Kia!!!!!Commercial!!Wednesday!!Key Makeup/Hair Kohl’s!!!!!Commercial!!Annie Fletcher!!Key Makeup/Hair CNBC!!!!!Commercial!!G.