Religious Fundamentalism in Zanskar, Indian Himalaya

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Compte Rendu De: Ladakhi Histories

Compte rendu de : Ladakhi Histories: Local and regional perspectives Pascale Dollfus To cite this version: Pascale Dollfus. Compte rendu de : Ladakhi Histories: Local and regional perspectives . 2006, pp.172- 177. halshs-01694592 HAL Id: halshs-01694592 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01694592 Submitted on 2 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 172 EBHR 29-30 Ladakhi Histories: Local and regional perspectives, edited by John Bray. Leiden: Brill (Tibetan Studies Library, 9). 2005. x + 406 pages, 36 maps, figures and plates, index. ISBN 90 04 14551 6. Reviewed by Pascale Dollfus, Paris. This volume illustrates the plurality of approaches to studying history and current research in the making. It compiles contributions – very different in length and in style – from researchers from a variety of disciplines: linguistics, tibetology, anthropology, history, art and archaeology. Their sources include linguistics, archaeological and artistical evidence; Tibetan chronicles, Persian biographies and European travel accounts; government records and private correspondence, land titles and trade receipts; oral tradition and reminiscence of survivors' recollections. The majority of the papers were first presented at the International Association of Ladakh Studies (IALS) conferences held in 1999, 2001 and 2003, and these have been supplemented by a few additional contributions. -

Impact of Climatic Change on Agro-Ecological Zones of the Suru-Zanskar Valley, Ladakh (Jammu and Kashmir), India

Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment Vol. 3(13), pp. 424-440, 12 November, 2011 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/JENE ISSN 2006 - 9847©2011 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Impact of climatic change on agro-ecological zones of the Suru-Zanskar valley, Ladakh (Jammu and Kashmir), India R. K. Raina and M. N. Koul* Department of Geography, University of Jammu, India. Accepted 29 September, 2011 An attempt was made to divide the Suru-Zanskar Valley of Ladakh division into agro-ecological zones in order to have an understanding of the cropping system that may be suitably adopted in such a high altitude region. For delineation of the Suru-Zanskar valley into agro-ecological zones bio-physical attributes of land such as elevation, climate, moisture adequacy index, soil texture, soil temperature, soil water holding capacity, slope, vegetation and agricultural productivity have been taken into consideration. The agricultural productivity of the valley has been worked out according to Bhatia’s (1967) productivity method and moisture adequacy index has been estimated on the basis of Subrmmanyam’s (1963) model. The land use zone map has been superimposed on moisture adequacy index, soil texture and soil temperature, soil water holding capacity, slope, vegetation and agricultural productivity zones to carve out different agro-ecological boundaries. The five agro-ecological zones were obtained. Key words: Agro-ecology, Suru-Zanskar, climatic water balance, moisture index. INTRODUCTION Mountain ecosystems of the world in general and India in degree of biodiversity in the mountains. particular face a grim reality of geopolitical, biophysical Inaccessibility, fragility, diversity, niche and human and socio economic marginality. -

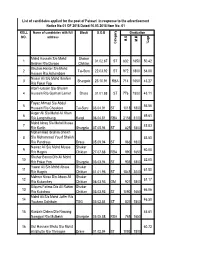

1 Mohd Hussain S/O Mohd Ibrahim R/O Dargoo Shakar Chiktan 01.02

List of candidates applied for the post of Patwari in response to the advertisement Notice No:01 OF 2018 Dated:10.03.2018 Item No: 01 ROLL Name of candidates with full Block D.O.B Graduation NO. address M.O M.M %age Category Category Mohd Hussain S/o Mohd Shakar 1 01.02.87 ST 832 1650 50.42 Ibrahim R/o Dargoo Chiktan Ghulam Haider S/o Mohd 2 Tai-Suru 22.03.92 ST 972 1800 54.00 Hassan R/o Achambore Nissar Ali S/o Mohd Ibrahim 3 Shargole 23.10.91 RBA 714 1650 43.27 R/o Fokar Foo Altaf Hussain S/o Ghulam 4 Hussain R/o Goshan Lamar Drass 01.01.88 ST 776 1800 43.11 Fayaz Ahmad S/o Abdul 5 56.56 Hussain R/o Choskore Tai-Suru 03.04.91 ST 1018 1800 Asger Ali S/o Mohd Ali Khan 6 69.61 R/o Longmithang Kargil 06.04.81 RBA 2158 3100 Mohd Ishaq S/o Mohd Mussa 7 45.83 R/o Karith Shargole 07.05.94 ST 825 1800 Mohammad Ibrahim Sheikh 8 S/o Mohammad Yousf Sheikh 53.50 R/o Pandrass Drass 05.09.94 ST 963 1800 Nawaz Ali S/o Mohd Mussa Shakar 9 60.00 R/o Hagnis Chiktan 27.07.88 RBA 990 1650 Shahar Banoo D/o Ali Mohd 10 52.00 R/o Fokar Foo Shargole 03.03.94 ST 936 1800 Yawar Ali S/o Mohd Abass Shakar 11 61.50 R/o Hagnis Chiktan 01.01.96 ST 1845 3000 Mehrun Nissa D/o Abass Ali Shakar 12 51.17 R/o Kukarchey Chiktan 06.03.93 OM 921 1800 Bilques Fatima D/o Ali Rahim Shakar 13 66.06 R/o Kukshow Chiktan 03.03.93 ST 1090 1650 Mohd Ali S/o Mohd Jaffer R/o 14 46.50 Youkma Saliskote TSG 03.02.84 ST 837 1800 15 Kunzais Dolma D/o Nawang 46.61 Namgyal R/o Mulbekh Shargole 05.05.88 RBA 769 1650 16 Gul Hasnain Bhuto S/o Mohd 60.72 Ali Bhutto R/o Throngos Drass 01.02.94 ST -

Reru Valley Expedition Proposal 2011

RERU VALLEY EXPEDITION PROPOSAL 2011 FOREWORD The destination of this expedition is to the Reru valley in the Zanskar range. This range is located in the north East of India in the state of Jammu and Kashmir, between the Great Himalayan range and the Ladakh range. Until 2009 there had been no climbing expeditions to the valley, and there are a large number of unclimbed summits between 5700m and 6200m in this area: only two of the 36 identified peaks have seen ascents. Our expedition aims to take a large group of 7 members that will use a single base camp but split into two teams that will attempt different types of objective. One team will focus on technical rock climbing ascents, whilst the other team will focus on alpine style mixed snow and rock ascents of unclimbed peaks with a target elevation of around 6000m. CONTENTS 1. Expedition Aims & Objectives ............................................................................................................................. 3 2. Background ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 3. Itinerary ............................................................................................................................................................. 12 4. Expedition Team ............................................................................................................................................... 13 5. Logistics ............................................................................................................................................................ -

{Download PDF} the Formation of the Colonial State in India 1St Edition

THE FORMATION OF THE COLONIAL STATE IN INDIA 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tony Cleaver | 9781134494293 | | | | | The Formation of the Colonial State in India 1st edition PDF Book Additionally, several Indian Princely States provided large donations to support the Allied campaign during the War. Under the charter, the Supreme Court, moreover, had the authority to exercise all types of jurisdiction in the region of Bengal, Bihar, and Odisha, with the only caveat that in situations where the disputed amount was in excess of Rs. During this age India's economy expanded, relative peace was maintained and arts were patronized. Routledge Handbook of Gender in South Asia. British Raj. Two four anna stamps issued in Description Contents Reviews Preview "Colonial and Postcolonial Geographies of India offers a good introduction to and basis for rethinking the ways in which academics theorize and teach the geographies of peoples, places, and regions. Circumscription theory Legal anthropology Left—right paradigm State formation Political economy in anthropology Network Analysis and Ethnographic Problems. With the constituting of the Ceded and Conquered Provinces in , the jurisdiction would extend as far west as Delhi. Contracts were awarded in to the East Indian Railway Company to construct a mile railway from Howrah -Calcutta to Raniganj ; to the Great Indian Peninsular Railway Company for a service from Bombay to Kalyan , thirty miles away; and to the Madras Railway Company for a line from Madras city to Arkonam , a distance of some thirty nine miles. The interdisciplinary work throws new light on pressing contemporary issues as well as on issues during the colonial period. -

Economic Impact of Colonialization Dr.Rajnish Kumar, Putulkumari

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 9 Issue 11 Ser. II || November 2020 || PP 01-11 Economic Impact of Colonialization 1Dr.Rajnish Kumar, 2PutulKumari 1Research scholarDept. of History 2Research Scholar Dept. of History B.R.A. Bihar University B.R.A. Bihar University Abstract The basic respect of the colonialization or peripheralization of India was its reduction to a producer of raw materials and importer of manufactures. This means that India as periphery of the world economy was assigned a specific role in the international division of labor. It was to Produce low technology, low productivity, law wage and low profit products in comparison to developed countries. This further deteriorated the economic condition of Indian people. The Indian economy grew at about 1% per year from 1880 to 1920 and the population also grew at 1%. The result was, on average, no long term change in income levels. Keywords:- Peripheralization, Colonialization, Developed Countries, Deteriorated, Economy etc. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- --------- Date of Submission: 08-11-2020 Date of Acceptance: 23-11-2020 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- I. BRITISH RULE After gaining the right to collect revenue in Bengal in 1765, the East India Company largely ceased importing gold and silver, which it had hitherto used to pay for goods shipped back to Britain. [2] In addition, as under Mughal rule, land revenue collected in the Bengal Presidency helped finance the Company's wars in other parts of India. [2] Consequently, in the period 1760–1800, Bengal's money supply was greatly diminished. The closing of some local mints and close supervision of the rest, the fixing of exchange rates and the standardization of coinage added to the economic downturn. -

Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19

Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 “STATISTICAL HANDBOOK” DISTRICT KARGIL UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH FOR THE YEAR 2018-19 RELEASED BY: DISTRICT STATISTICAL & EVALUATION OFFICE KARGIL D.C OFFICE COMPLEX BAROO KARGIL J&K. TELE/FAX: 01985-233973 E-MAIL: [email protected] Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 THE ADMINISTRATION OF UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH, Chairman/ Chief Executive Councilor, LAHDC Kargil Phone No: 01985 233827, 233856 Message It gives me immense pleasure to know that District Statistics & Evaluation Agency Kargil is coming up with the latest issue of its ideal publication “Statistical Handbook 2018-19”. The publication is of paramount importance as it contains valuable statistical profile of different sectors of the district. I hope this Hand book will be useful to Administrators, Research Scholars, Statisticians and Socio-Economic planners who are in need of different statistics relating to Kargil District. I appreciate the efforts put in by the District Statistics & Evaluation Officer and the associated team of officers and officials in bringing out this excellent broad based publication which is getting a claim from different quarters and user agencies. Sd/= (Feroz Ahmed Khan ) Chairman/Chief Executive Councilor LAHDC, Kargil Statistical Handbook District Kargil 2018-19 THE ADMINISTRATION OF UNION TERRITORY OF LADAKH District Magistrate, (Deputy Commissioner/CEO) LAHDC Kargil Phone No: 01985-232216, Tele Fax: 232644 Message I am glad to know that the district Statistics and Evaluation Office Kargil is releasing its latest annual publication “Statistical Handbook” for the year 2018- 19. The present publication contains statistics related to infrastructure as well as Socio Economic development of Kargil District. -

The Decline of Buddhism in India

The Decline of Buddhism in India It is almost impossible to provide a continuous account of the near disappearance of Buddhism from the plains of India. This is primarily so because of the dearth of archaeological material and the stunning silence of the indigenous literature on this subject. Interestingly, the subject itself has remained one of the most neglected topics in the history of India. In this book apart from the history of the decline of Buddhism in India, various issues relating to this decline have been critically examined. Following this methodology, an attempt has been made at a region-wise survey of the decline in Sind, Kashmir, northwestern India, central India, the Deccan, western India, Bengal, Orissa, and Assam, followed by a detailed analysis of the different hypotheses that propose to explain this decline. This is followed by author’s proposed model of decline of Buddhism in India. K.T.S. Sarao is currently Professor and Head of the Department of Buddhist Studies at the University of Delhi. He holds doctoral degrees from the universities of Delhi and Cambridge and an honorary doctorate from the P.S.R. Buddhist University, Phnom Penh. The Decline of Buddhism in India A Fresh Perspective K.T.S. Sarao Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-215-1241-1 First published 2012 © 2012, Sarao, K.T.S. All rights reserved including those of translation into other languages. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. -

Ladakh Studies

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR LADAKH STUDIES LADAKH STUDIES _ 19, March 2005 CONTENTS Page: Editorial 2 News from the Association: From the Hon. Sec. 3 Nicky Grist - In Appreciation John Bray 4 Call for Papers: 12th Colloquium at Kargil 9 News from Ladakh, including: Morup Namgyal wins Padmashree Thupstan Chhewang wins Ladakh Lok Sabha seat Composite development planned for Kargil News from Members 37 Articles: The Ambassador-Teacher: Reflections on Kushok Bakula Rinpoche's Importance in the Revival of Buddhism in Mongolia Sue Byrne 38 Watershed Development in Central Zangskar Seb Mankelow 49 Book reviews: A Checklist on Medicinal & Aromatic Plants of Trans-Himalayan Cold Desert (Ladakh & Lahaul-Spiti), by Chaurasia & Gurmet Laurent Pordié 58 The Issa Tale That Will Not Die: Nicholas Notovitch and his Fraudulent Gospel, by H. Louis Fader John Bray 59 Trance, Besessenheit und Amnesie bei den Schamanen der Changpa- Nomaden im Ladakhischen Changthang, by Ina Rösing Patrick Kaplanian 62 Thesis reviews 63 New books 66 Bray’s Bibliography Update no. 14 68 Notes on Contributors 72 Production: Bristol University Print Services. Support: Dept of Anthropology and Ethnography, University of Aarhus. 1 EDITORIAL I should begin by apologizing for the fact that this issue of Ladakh Studies, once again, has been much delayed. In light of this, we have decided to extend current subscriptions. Details are given elsewhere in this issue. Most recently we postponed publication, because we wanted to be able to announce the place and exact dates for the upcoming 12th Colloquium of the IALS. We are very happy and grateful that our members in Kargil will host the colloquium from July 12 through 15, 2005. -

Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh ¾-Hðgå-ÅÛ-Hýh-ºiô-;Ým-Mû-Ç+Ô¼-¾-Zçàz-Çeômü

Field Guide Mammals of Ladakh ¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-hÝh-ºIô-;Ým-mÛ-Ç+ô¼-¾-zÇÀz-Çeômü Tahir Shawl Jigmet Takpa Phuntsog Tashi Yamini Panchaksharam 2 FOREWORD Ladakh is one of the most wonderful places on earth with unique biodiversity. I have the privilege of forwarding the fi eld guide on mammals of Ladakh which is part of a series of bilingual (English and Ladakhi) fi eld guides developed by WWF-India. It is not just because of my involvement in the conservation issues of the state of Jammu & Kashmir, but I am impressed with the Ladakhi version of the Field Guide. As the Field Guide has been specially produced for the local youth, I hope that the Guide will help in conserving the unique mammal species of Ladakh. I also hope that the Guide will become a companion for every nature lover visiting Ladakh. I commend the efforts of the authors in bringing out this unique publication. A K Srivastava, IFS Chief Wildlife Warden, Govt. of Jammu & Kashmir 3 ÇSôm-zXôhü ¾-hÐGÅ-mÛ-ºWÛG-dïm-mP-¾-ÆôG-VGÅ-Ço-±ôGÅ-»ôh-źÛ-GmÅ-Å-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-ŸÛG-»Ûm-môGü ¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-Å-GmÅ-;Ým-¾-»ôh-qºÛ-Åï¤Å-Tm-±P-¤ºÛ-MãÅ-‚Å-q-ºhÛ-¾-ÇSôm-zXôh-‚ô-‚Å- qôºÛ-PºÛ-¾Å-ºGm-»Ûm-môGü ºÛ-zô-P-¼P-W¤-¤Þ-;-ÁÛ-¤Û¼-¼Û-¼P-zŸÛm-D¤-ÆâP-Bôz-hP- ºƒï¾-»ôh-¤Dm-qôÅ-‚Å-¼ï-¤m-q-ºÛ-zô-¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-Ç+h-hï-mP-P-»ôh-‚Å-qôº-È-¾Å-bï-»P- zÁh- »ôPÅü Åï¤Å-Tm-±P-¤ºÛ-MãÅ-‚ô-‚Å-qô-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-¾ÛÅ-GŸôm-mÝ-;Ým-¾-wm-‚Å-¾-ºwÛP-yï-»Ûm- môG ºô-zôºÛ-;-mÅ-¾-hÐGÅ-ÅÛ-h¤ÛGÅ-zž-Tm-mÛ-Åï¤Å-Tm-ÆâP-BôzÅ-¾-wm-qºÛ-¼Û-zô-»Ûm- hôm-m-®ôGÅ-¾ü ¼P-zŸÛm-D¤Å-¾-ºfh-qô-»ôh-¤Dm-±P-¤-¾ºP-wm-fôGÅ-qºÛ-¼ï-z-»Ûmü ºhÛ-®ßGÅ-ºô-zM¾-¤²h-hï-ºƒÛ-¤Dm-mÛ-ºhÛ-hqï-V-zô-q¼-¾-zMz-Çeï-Çtï¾-hGôÅ-»Ûm-môG Íï-;ï-ÁÙÛ-¶Å-b-z-ͺÛ-Íïw-ÍôÅ- mGÅ-±ôGÅ-Åï¤Å-Tm-ÆâP-Bôz-Çkï-DG-GÛ-hqôm-qô-G®ô-zô-W¤- ¤Þ-;ÁÛ-¤Û¼-GŸÝP.ü 4 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The fi eld guide is the result of exhaustive work by a large number of people. -

The Importance of Being Ladakhi: Affect and Artifice in Kargil

Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 32 Number 1 Ladakh: Contemporary Publics and Politics Article 13 No. 1 & 2 8-1-2013 The mpI ortance of Being Ladakhi: Affect and Artifice in Kargil Radhika Gupta Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious & Ethnic Diversity, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Gupta, Radhika (2012) "The mporI tance of Being Ladakhi: Affect and Artifice in Kargil," Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: Vol. 32: No. 1, Article 13. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol32/iss1/13 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RADHIKA GUPTA MAX PLANCK INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF RELIGIOUS & ETHNIC DIVERSITY THE IMPORTANCE OF BEING LADAKHI: AFFECT AND ARTIFICE IN KARGIL Ladakh often tends to be associated predominantly with its Tibetan Buddhist inhabitants in the wider public imagination both in India and abroad. It comes as a surprise to many that half the population of this region is Muslim, the majority belonging to the Twelver Shi‘i sect and living in Kargil district. This article will discuss the importance of being Ladakhi for Kargili Shias through an ethnographic account of a journey I shared with a group of cultural activists from Leh to Kargil. -

Spread of Buddhism in Ladakh (From 2 BCE to 9

Spread of Buddhism in Ladakh (From 2nd BCE to 9th CE) Dr. Mohd Ashraf Dar Cont. Assistant Professor, Department of History, Cluster University, Srinagar Abstract: Jammu and Kashmir State of India is still a blooming orchard of Buddhism. In this paper an attempt has been made to analyse how Buddhism reached Ladakh and why it is flourishing there till date. Oral traditions have also been used in this study. During the course of present study, Interdisciplinary approach of research methodology has been applied. Key Words: Ladakh, Buddhism, Bon-chos, Lamaism, Tantra, Tibetan Buddhism Introduction: Buddhism as a new religion was born in India and soon became the faith of multitude especially in the Gangetic region. It got the patronage of some powerful monarchs especially Asoka Maurya and Kaniska . It is generally believed that Buddhism spread to the other regions of India as well as outside the India due to the zealous efforts of missionaries for which monasteries provided a strong base. Kashmir the immediate neighbor of Ladakh got the gospel of Buddha as depicted in some primary sources regarding the history of Kashmir like Rajtarangini as early as 2nd BCE. Kashmir remained the hub of Buddhism for next 11 centuries till it was ousted from Kashmir as from the other parts of India. Ladakh is perhaps the only region in India where Buddhism not only remained till date but flourished as well. It even was able to sustain itself after the introduction of Islam to this region by Syed Ali Hamdani. What matters most here is to know when and to whom was the gospel of Buddha preached in Ladakh.