Intro to Language – Basic Concepts of Linguistics Jirka Hana – March 7, 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Grammar

Traditional Grammar Traditional grammar refers to the type of grammar study Continuing with this tradition, grammarians in done prior to the beginnings of modern linguistics. the eighteenth century studied English, along with many Grammar, in this traditional sense, is the study of the other European languages, by using the prescriptive structure and formation of words and sentences, usually approach in traditional grammar; during this time alone, without much reference to sound and meaning. In the over 270 grammars of English were published. During more modern linguistic sense, grammar is the study of the most of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, grammar entire interrelated system of structures— sounds, words, was viewed as the art or science of correct language in meanings, sentences—within a language. both speech and writing. By pointing out common Traditional grammar can be traced back over mistakes in usage, these early grammarians created 2,000 years and includes grammars from the classical grammars and dictionaries to help settle usage arguments period of Greece, India, and Rome; the Middle Ages; the and to encourage the improvement of English. Renaissance; the eighteenth and nineteenth century; and One of the most influential grammars of the more modern times. The grammars created in this eighteenth century was Lindley Murray’s English tradition reflect the prescriptive view that one dialect or grammar (1794), which was updated in new editions for variety of a language is to be valued more highly than decades. Murray’s rules were taught for many years others and should be the norm for all speakers of the throughout school systems in England and the United language. -

Logophoricity in Finnish

Open Linguistics 2018; 4: 630–656 Research Article Elsi Kaiser* Effects of perspective-taking on pronominal reference to humans and animals: Logophoricity in Finnish https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0031 Received December 19, 2017; accepted August 28, 2018 Abstract: This paper investigates the logophoric pronoun system of Finnish, with a focus on reference to animals, to further our understanding of the linguistic representation of non-human animals, how perspective-taking is signaled linguistically, and how this relates to features such as [+/-HUMAN]. In contexts where animals are grammatically [-HUMAN] but conceptualized as the perspectival center (whose thoughts, speech or mental state is being reported), can they be referred to with logophoric pronouns? Colloquial Finnish is claimed to have a logophoric pronoun which has the same form as the human-referring pronoun of standard Finnish, hän (she/he). This allows us to test whether a pronoun that may at first blush seem featurally specified to seek [+HUMAN] referents can be used for [-HUMAN] referents when they are logophoric. I used corpus data to compare the claim that hän is logophoric in both standard and colloquial Finnish vs. the claim that the two registers have different logophoric systems. I argue for a unified system where hän is logophoric in both registers, and moreover can be used for logophoric [-HUMAN] referents in both colloquial and standard Finnish. Thus, on its logophoric use, hän does not require its referent to be [+HUMAN]. Keywords: Finnish, logophoric pronouns, logophoricity, anti-logophoricity, animacy, non-human animals, perspective-taking, corpus 1 Introduction A key aspect of being human is our ability to think and reason about our own mental states as well as those of others, and to recognize that others’ perspectives, knowledge or mental states are distinct from our own, an ability known as Theory of Mind (term due to Premack & Woodruff 1978). -

Syntax and Morphology Semantics

Parent Tip Sheet Language Syntax & Morphology yntax is the development of sentence structure meaning your child’s first attempts at putting two words together. SMorphology refers to the structure and construction of words and the rules that determine changes in word meaning; it’s knowing plural forms 9 and correct use of verb tense. Introduce words from many different categories: nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions and conjunctions. The emergence of first words 9 typically begins around 12 months of Use the Plus One Rule: add a word to expand the length of your child’s utterance to model longer sentences. Also use correct grammar, even age. Syntax typically begins when if it means adding more than one word. E.g., if your child says ‘blue a child begins to combine words in ball” you can say “The blue ball is big.” early two word utterances (ex. Daddy 9 work) around 18-24 months. Read books with repetition, such as: We’re Going on a Bear Hunt or I Went Walking. 9 A child needs approximately 50 Watch videos of people or objects in action and describe what is happening. words to begin to combine them 9 Pay attention to the use of plurals with an “s”, add them whenever into short phrases. When children possible. Point out words that do not use an “s” to be plural (e.g., men, begin to learn words, they learn that children) to understand placement in space. some words refer to objects, some 9 Play games with “in” and “on.” To focus on correlation with space. -

Applying Phonology in Lexicography: Variant-Synonym Classification In

Applying phonology in lexicography: variant-synonym classification in Czech Sign Language Hana Strachoňová, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic, [email protected] Lucia Vlášková, Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic, [email protected] Sign language (SL) lexicography, as a young field of study within SL linguistics, faces a lot of challenges that have already been answered for the audio-oral language material. In this talk we present a method that is being applied in the ongoing process of data classification for the first Czech SL online dictionary (part of the platform Dictio). Problem: For audio-oral languages, a dictionary entry standardly contains the citation form of a lexeme and all the variants (Čermák 1995). See for example the gender variants in Czech: brambor (potato- masculine) / brambor-a (potato-feminine), hadr (cloth-masculine) / hadr-a (cloth-feminine). However, two (or more) expressions of a different word-forming nature are not considered variants but synonyms (Filipec 1995). See the example pairs in Czech - the first expression comes from the traditional Czech lexicon and the latter originates in English/Latin: jazykověda (linguistics; Czech origin) / lingvistika (linguistics; foreign origin), poradce (consultant; Czech origin) / konzultant (consultant; foreign origin). The common ground of the variant- and synonym-pairs is their shared meaning (brambor has the same meaning as brambora; jazykověda has the same meaning as lingvistika) and in the lexicographic work it is essential to assign each of them the right place in the dictionary entry. What seems as a simple task for spoken languages (basically - common root for variants, different roots for synonyms) becomes a challenge for SLs (still ongoing discussion about the definition of morphemes and lexical roots; see e.g. -

II Levels of Language

II Levels of language 1 Phonetics and phonology 1.1 Characterising articulations 1.1.1 Consonants 1.1.2 Vowels 1.2 Phonotactics 1.3 Syllable structure 1.4 Prosody 1.5 Writing and sound 2 Morphology 2.1 Word, morpheme and allomorph 2.1.1 Various types of morphemes 2.2 Word classes 2.3 Inflectional morphology 2.3.1 Other types of inflection 2.3.2 Status of inflectional morphology 2.4 Derivational morphology 2.4.1 Types of word formation 2.4.2 Further issues in word formation 2.4.3 The mixed lexicon 2.4.4 Phonological processes in word formation 3 Lexicology 3.1 Awareness of the lexicon 3.2 Terms and distinctions 3.3 Word fields 3.4 Lexicological processes in English 3.5 Questions of style 4 Syntax 4.1 The nature of linguistic theory 4.2 Why analyse sentence structure? 4.2.1 Acquisition of syntax 4.2.2 Sentence production 4.3 The structure of clauses and sentences 4.3.1 Form and function 4.3.2 Arguments and complements 4.3.3 Thematic roles in sentences 4.3.4 Traces 4.3.5 Empty categories 4.3.6 Similarities in patterning Raymond Hickey Levels of language Page 2 of 115 4.4 Sentence analysis 4.4.1 Phrase structure grammar 4.4.2 The concept of ‘generation’ 4.4.3 Surface ambiguity 4.4.4 Impossible sentences 4.5 The study of syntax 4.5.1 The early model of generative grammar 4.5.2 The standard theory 4.5.3 EST and REST 4.5.4 X-bar theory 4.5.5 Government and binding theory 4.5.6 Universal grammar 4.5.7 Modular organisation of language 4.5.8 The minimalist program 5 Semantics 5.1 The meaning of ‘meaning’ 5.1.1 Presupposition and entailment 5.2 -

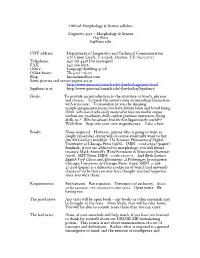

Official! Morphology & Syntax Syllabus

Official Morphology & Syntax syllabus Linguistics 4050 – Morphology & Syntax Haj Ross [email protected] UNT address: Department of Linguistics and Technical Communication 1155 Union Circle, # 305298, Denton, TX 76203-5017 Telephone: 940 565 4458 [for messages] FAX: 940 369 8976 Office: Language Building 407K Office hours: Th 4:00 – 6:00 Blog: haj.nadamelhor.com Some poetics and syntax papers are at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~jlawler/hajpapers.html Squibnet is at http://www-personal.umich.edu/~jlawler/haj/Squibnet/ Goals: To provide an introduction to the structure of words, phrases and clauses. To hook the unwary into an unending fascination with structure. To reawaken in you the sleeping morphopragmantactician you have always been and loved being. (Hint: who was it who easily mastered at least one mother tongue without any vocabulary drills, explicit grammar instruction, boring drills, etc.? Who has always been the best linguist in the world??) Well then. Step into your own magnificence. Take a bow. Books: None required. However, anyone who is going to want to deeply remember syntax will of course eventually want to buy Jim McCawley’s indelible The Syntactic Phenomena of English University of Chicago Press (1988). ISBN: 0226556247 (paper). Similarly, if you are addicted to morphology, you will always treasure Mark Aronoff’s Word Formation in Generative Grammar (1976). MIT Press. ISBN: 0-262-51017-0. And Beth Levin’s English Verb Classes and Alternations: A Preliminary Investigation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (1993) ISBN 0-226- 47533-6 (paper) is a delicious cookie jar of weird (and unweird) classes of verbs that you may have thought you had forgotten since you were three. -

Language Development Language Development

Language Development rom their very first cries, human beings communicate with the world around them. Infants communicate through sounds (crying and cooing) and through body lan- guage (pointing and other gestures). However, sometime between 8 and 18 months Fof age, a major developmental milestone occurs when infants begin to use words to speak. Words are symbolic representations; that is, when a child says “table,” we understand that the word represents the object. Language can be defined as a system of symbols that is used to communicate. Although language is used to communicate with others, we may also talk to ourselves and use words in our thinking. The words we use can influence the way we think about and understand our experiences. After defining some basic aspects of language that we use throughout the chapter, we describe some of the theories that are used to explain the amazing process by which we Language9 A system of understand and produce language. We then look at the brain’s role in processing and pro- symbols that is used to ducing language. After a description of the stages of language development—from a baby’s communicate with others or first cries through the slang used by teenagers—we look at the topic of bilingualism. We in our thinking. examine how learning to speak more than one language affects a child’s language develop- ment and how our educational system is trying to accommodate the increasing number of bilingual children in the classroom. Finally, we end the chapter with information about disorders that can interfere with children’s language development. -

Toward a Shared Syntax for Shifted Indexicals and Logophoric Pronouns

Toward a Shared Syntax for Shifted Indexicals and Logophoric Pronouns Mark Baker Rutgers University April 2018 Abstract: I argue that indexical shift is more like logophoricity and complementizer agreement than most previous semantic accounts would have it. In particular, there is evidence of a syntactic requirement at work, such that the antecedent of a shifted “I” must be a superordinate subject, just as the antecedent of a logophoric pronoun or the goal of complementizer agreement must be. I take this to be evidence that the antecedent enters into a syntactic control relationship with a null operator in all three constructions. Comparative data comes from Magahi and Sakha (for indexical shift), Yoruba (for logophoric pronouns), and Lubukusu (for complementizer agreement). 1. Introduction Having had an office next to Lisa Travis’s for 12 formative years, I learned many things from her that still influence my thinking. One is her example of taking semantic notions, such as aspect and event roles, and finding ways to implement them in syntactic structure, so as to advance the study of less familiar languages and topics.1 In that spirit, I offer here some thoughts about how logophoricity and indexical shift, topics often discussed from a more or less semantic point of view, might have syntactic underpinnings—and indeed, the same syntactic underpinnings. On an impressionistic level, it would not seem too surprising for logophoricity and indexical shift to have a common syntactic infrastructure. Canonical logophoricity as it is found in various West African languages involves using a special pronoun inside the finite CP complement of a verb to refer to the subject of that verb. -

Basic Morphology

What is Morphology? Mark Aronoff and Kirsten Fudeman MORPHOLOGY AND MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS 1 1 Thinking about Morphology and Morphological Analysis 1.1 What is Morphology? 1 1.2 Morphemes 2 1.3 Morphology in Action 4 1.3.1 Novel words and word play 4 1.3.2 Abstract morphological facts 6 1.4 Background and Beliefs 9 1.5 Introduction to Morphological Analysis 12 1.5.1 Two basic approaches: analysis and synthesis 12 1.5.2 Analytic principles 14 1.5.3 Sample problems with solutions 17 1.6 Summary 21 Introduction to Kujamaat Jóola 22 mor·phol·o·gy: a study of the structure or form of something Merriam-Webster Unabridged n 1.1 What is Morphology? The term morphology is generally attributed to the German poet, novelist, playwright, and philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832), who coined it early in the nineteenth century in a biological context. Its etymology is Greek: morph- means ‘shape, form’, and morphology is the study of form or forms. In biology morphology refers to the study of the form and structure of organisms, and in geology it refers to the study of the configuration and evolution of land forms. In linguistics morphology refers to the mental system involved in word formation or to the branch 2 MORPHOLOGYMORPHOLOGY ANDAND MORPHOLOGICAL MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS ANALYSIS of linguistics that deals with words, their internal structure, and how they are formed. n 1.2 Morphemes A major way in which morphologists investigate words, their internal structure, and how they are formed is through the identification and study of morphemes, often defined as the smallest linguistic pieces with a gram- matical function. -

Phonetic and Phonological Research Sharing Methods

The Kabod Volume 3 Issue 3 Summer Article 1 January 2017 Phonetic and Phonological Research Sharing Methods Cory C. Coogan Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/kabod Part of the Modern Languages Commons, and the Reading and Language Commons Recommended Citations MLA: Coogan, Cory C. "Phonetic and Phonological Research Sharing Methods," The Kabod 3. 3 (2017) Article 1. Liberty University Digital Commons. Web. [xx Month xxxx]. APA: Coogan, Cory C. (2017) "Phonetic and Phonological Research Sharing Methods" The Kabod 3( 3 (2017)), Article 1. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/kabod/vol3/iss3/1 Turabian: Coogan, Cory C. "Phonetic and Phonological Research Sharing Methods" The Kabod 3 , no. 3 2017 (2017) Accessed [Month x, xxxx]. Liberty University Digital Commons. This Individual Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kabod by an authorized editor of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Coogan: Phonetic and Phonological Research Sharing Methods Running Head: PHONETIC AND PHONOLOGICAL RESEARCH SHARING METHODS 1 Phonetic and Phonological Research Sharing Methods Cory Coogan Liberty University Published by Scholars Crossing, 2017 1 The Kabod, Vol. 3, Iss. 3 [2017], Art. 1 PHONETIC AND PHONOLOGICAL RESEARCH SHARING METHODS 2 Phonetic and Phonological Research Sharing Methods Most linguists affirm the observation that human language is innate; the human mind has a capacity for grammar that is inherent from birth. This notion implies that a singular grammar produces all human languages; therefore, to appropriately understand the scope of the human capacity for grammar, a single model must cohesively describe the various processes of all human languages. -

Implementing the Morphology-Syntax Interface: Challenges from Murrinh-Patha Verbs

IMPLEMENTING THE MORPHOLOGY-SYNTAX INTERFACE: CHALLENGES FROM MURRINH-PATHA VERBS Melanie Seiss Universitat¨ Konstanz Proceedings of the LFG11 Conference Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King (Editors) 2011 CSLI Publications http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/ Abstract Polysynthetic languages pose special challenges for the morphology- syntax interface because information otherwise associated with words, phrases and clauses is encoded in a single morphological word. In this pa- per, I am concerned with the implementation of the verbal structure of the polysynthetic language Murrinh-Patha and the questions this raises for the morphology-syntax interface. 1 Introduction The interface between morphology and syntax has been a matter of great de- bate, both for theoretical linguistics and for grammar implementation (see, e.g. the discussions in Sadler and Spencer 2004). Polysynthetic languages pose special challenges for this interface because information otherwise associated with words, phrases and clauses is encoded in a single morphological word. In this paper, I am concerned with the implementation of the verbal structure of the polysynthetic language Murrinh-Patha and the questions this raises for the morphology-syntax interface. The Murrinh-Patha grammar is implemented with the grammar development platform XLE (Crouch et al. 2011) and uses an XFST finite state morphology (Beesley and Karttunen 2003). As Frank and Zaenen (2004) point out, a morphol- ogy module like this in combination with sublexical rules makes a lexicon with fully inflected forms unnecessary, which is especially important for a polysyn- thetic language as listing all possible morphological words would be unfeasible, if not impossible. However, this raises the question of the division of work be- tween syntactic grammar rules in XLE and morphological formations in XFST. -

24.900 Intro to Linguistics Lecture Notes: Phonology Summary

Fall 2012 Phonology Summary • Speakers of English learned something from the data they were presented with as (contains all examples from class slides, and more!) babies that caused them to internalize (learn) the rule exemplified in (1) — just as Tojolabal speakers learned from the data that they heard as babies, and ended up with 1. Phonology vs. phonetics the rule exemplified in (2). • The path from memory (lexical access) to speech is mediated by phonology. • The English rule is real and active "on-line", governing creative linguistic behavior. A • Phonology = system of rules that apply when speech sounds are put together to form native speaker of English will apply it to new words they have never heard. The /t/ in morphemes and words. tib will be aspirated, and the /t/ in stib (both nonsense words, I hope) will not be. Probably Tojolabal speakers will show similar behavior with respect to their rule. (1) stop consonant aspiration in English: initial within a stressed syllable ASPIRATED UNASPIRATED 2. What phonetic distinctions are made in lexical entries? initial within a stressed syllable after s or initial within an word-final (therefore syllable- Part 1: phonological rules that eliminate distinctions from the lexicon unstressed syllable final) pan span nap tone stone note • English: lexicon does not need to distinguish aspirated from unaspirated stops. kin skin nick There is no reason to suppose that information about aspiration forms part of the sound field of lexical entries of English words, since it is entirely predictable. Though pan is upon supping pronounced /pʰæn/ and span /spæn/, there is no reason to distinguish the aspirated and unaspirated bilabial stops in the lexical entries of the two words.