Irish Science Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Materialism in Ian Mcdonald's Novel the Dervish House

English Language and Literature E-Journal / ISSN 2302-3546 MATERIALISM IN IAN MCDONALD’S NOVEL THE DERVISH HOUSE Yogi Sulendra 1, Kurnia Ningsih 2, Muhammad Al-Hafizh 3 Program Studi Bahasa Dan Sastra Inggris FBS Universitas Negeri Padang email: [email protected] Abstrak Tujuan penelitian ini adalah (1) menganalisa sejauh mana novel ini merefleksikan materialism, (2) menunjukkan kontribusi elemen fiksi (karakter, alur (konflik), dan seting) dalam mengungkap materialism dalam novel ini. Data penelitian ini adalah teks tertulis yang dikutip dari novel. Kutipan teks tersebut kemudian diinterpretasi dan dianalisa dengan elemen fiksi (karakter, alur (konflik), dan seting), lalu dikaitkan dengan konsep materialism yang dijelaskan oleh Marsha L. Richins, Scott Dawson, dan Russel W. Belk serta teori human motivation yang dirumuskan oleh Abraham Maslow. Hasil analisa menunjukkan bahwa dua karakter dalam novel ini melakukan tindakan-tindakan seorang yang materialistis untuk mencapai tujuan utama dalam hidup mereka, yaitu memiliki sebanyak mungkin materi, khususnya uang. Mereka sangat brilian dalam melihat kesempatan - kesempatan dalam melakukan bisnis. Mereka juga memiliki ambisi yang berlebihan dalam bekerja. Key words: materialism, materialistic, goal, material, money, brilliant, opportunities, excessive, ambition A. Introduction Having capability to fulfill needs in life is the goal of most of people. Everyone wants to have an established life. However, they have different view about what established life means. Some people have already felt satisfied with their life if they at least can fulfill their basic needs, such as food, clothes, and shelter. Others never feel satisfied, though they have already had more than what they need. These people have high level of desire to have more possession. -

The Foundations of the Valuation of Insurance Liabilities

The foundations of the valuation of insurance liabilities Philipp Keller 14 April 2016 Audit. Tax. Consulting. Financial Advisory. Content • The importance and complexity of valuation • The basics of valuation • Valuation and risk • Market consistent valuation • The importance of consistency of market consistency • Financial repression and valuation under pressure • Hold-to-maturity • Conclusions and outlook 2 The foundations of the valuation of insurance liabilities The importance and complexity of valuation 3 The foundations of the valuation of insurance liabilities Valuation Making or breaking companies and nations Greece: Creative accounting and valuation and swaps allowed Greece to satisfy the Maastricht requirements for entering the EUR zone. Hungary: To satisfy the Maastricht requirements, Hungary forced private pension-holders to transfer their pensions to the public pension fund. Hungary then used this pension money to plug government debts. Of USD 15bn initially in 2011, less than 1 million remained at 2013. This approach worked because the public pension fund does not have to value its liabilities on an economic basis. Ireland: The Irish government issued a blanket state guarantee to Irish banks for 2 years for all retail and corporate accounts. Ireland then nationalized Anglo Irish and Anglo Irish Bank. The total bailout cost was 40% of GDP. US public pension debt: US public pension debt is underestimated by about USD 3.4 tn due to a valuation standard that grossly overestimates the expected future return on pension funds’ asset. (FT, 11 April 2016) European Life insurers: European life insurers used an amortized cost approach for the valuation of their life insurance liability, which allowed them to sell long-term guarantee products. -

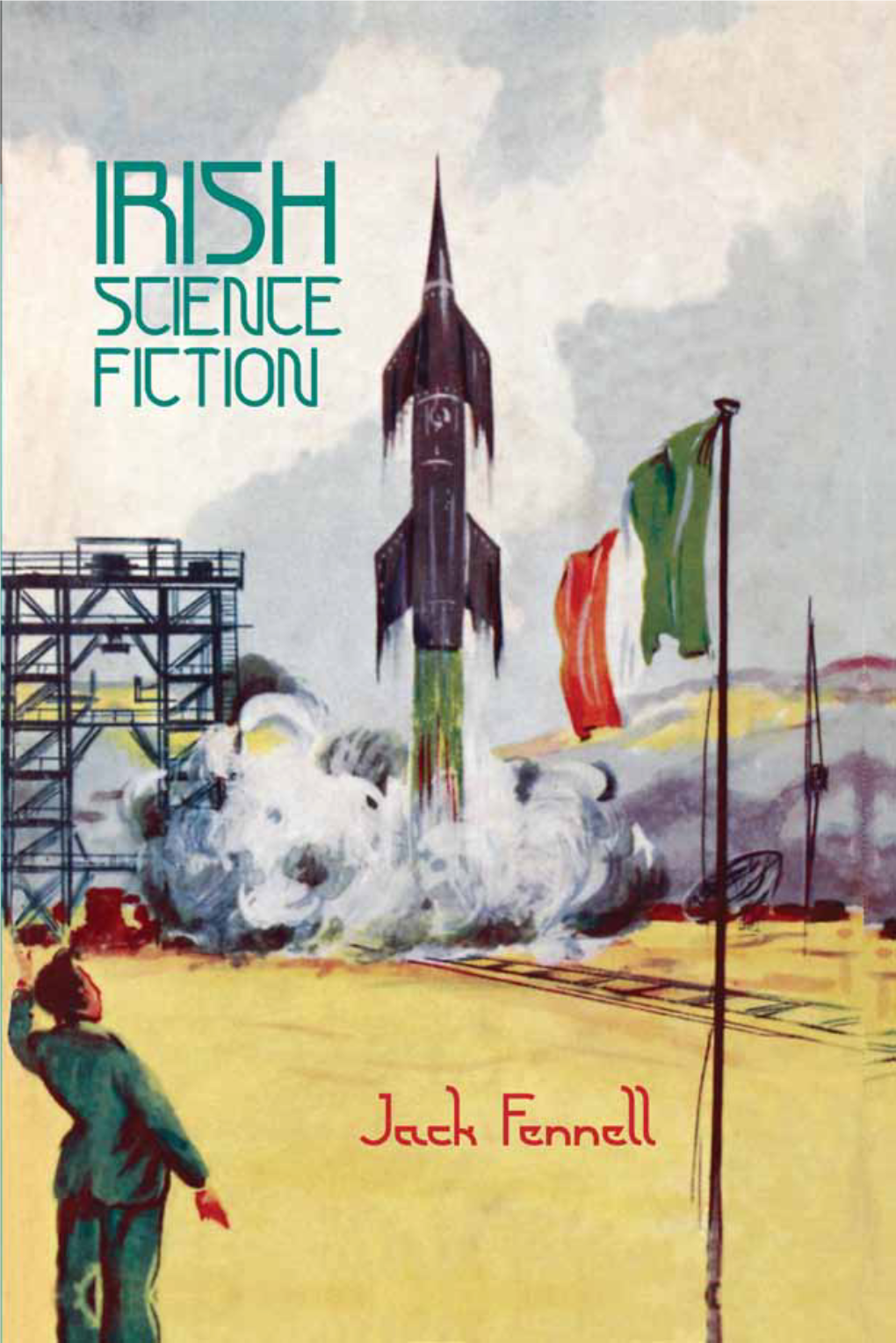

A Short Guide to Irish Science Fiction

A Short Guide to Irish Science Fiction Jack Fennell As part of the Dublin 2019 Bid, we run a weekly feature on our social media platforms since January 2015. Irish Fiction Friday showcases a piece of free Irish Science Fiction, Fantasy or Horror literature every week. During this, we contacted Jack Fennell, author of Irish Science Fiction, with an aim to featuring him as one of our weekly contributors. Instead, he gave us this wonderful bibliography of Irish Science Fiction to use as we saw fit. This booklet contains an in-depth list of Irish Science Fiction, details of publication and a short synopsis for each entry. It gives an idea of the breadth of science fiction literature, past and present. across a range of writers. It’s a wonderful introduction to Irish Science Fiction literature, and we very much hope you enjoy it. We’d like to thank Jack Fennell for his huge generosity and the time he has donated in putting this bibliography together. His book, Irish Science Fiction, is available from Liverpool University Press. http://liverpooluniversitypress.co.uk/products/60385 The cover is from Cathal Ó Sándair’s An Captaen Spéirling, Spás-Phíolóta (1961). We’d like to thank Joe Saunders (Cathal’s Grandson) for allowing us to reprint this image. Find out more about the Bid to host a Worldcon in Dublin 2019 on our webpage: www.dublin2019.com, and on our Facebook page; Dublin2019. You can also mail us at [email protected] Dublin 2019 Committee Anonymous. The Battle of the Moy; or, How Ireland Gained Her Independence, 1892-1894. -

Systems and Knowledge Science Fiction Research Association, 2016

Systems and Knowledge #SFRA2016 Science Fiction Research Association, 2016 The University of Liverpool 28th – 30th June Love, 3039 A.D. – “Darling, whenever you’re near me, my sub-atomic dynamo revs faster and faster………….”* *From the cover of The Satellite, vol. 2 iss. 5, May 1939 2 Contents Contents ............................................................................................................................................................................ 2 Conference Schedule ........................................................................................................................................................ 7 Tuesday 28th June, 2016; 10:00 – 11:30 ...................................................................................................................... 10 Keynote: Sawyer, Andy (The University of Liverpool) – #wearealljonsnow or, The Mystery of the Face in the Mirror: Some Problems in Research ........................................................................................................................................ 10 Tuesday 28th June, 2016; 11:45 – 12:45 ...................................................................................................................... 10 Gaslighting (Lecture Theatre 2) Chair: Sarah Lohmann .............................................................................................. 10 Lear, Ashley (Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University) and Jeanette B. Barott (Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE)) – Applications for Gaslighting -

Speculative Fiction for the Future of Man and Civilization

Speculative Fiction for the Future of Man and Civilization Bogdan Trocha1 Doctor of Science (Philology), Professor, University of Zielona Góra (Zielona Góra, Poland) E-mail: [email protected] https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2348-4813 The main thesis of the article is the comparison of speculative fiction with the challenges facing modern man. Introductory questions are two issues. How can fantasy become the subject of cultural reflection on the future of human civilization? Can contemporary speculative fistion act as an instructional story about the unknown? The author indicates several basic models of using speculative fiction. However, it limits itself to creating an introductory canon, which is associated with literary speculations regarding the impact of man and technology on the future of civilization. Keywords: myth, speculative fiction, political fiction, space opera, postapocalyptic fiction, ecological science fiction Received: September 11, 2019; accepted: October 5, 2019 Future Human Image, Volume 12, 2019: 104-114. https://doi.org/10.29202/fhi/12/9 In the face of the unknown — in search of model stories: myth, fantasy, speculative fiction The notion of speculative fiction has been firmly established in popular culture for many years. However, while it is very easy to point to the essential features of the poetics of this type of novel, it is much more difficult to point to the cultural paradigm from which both speculative fiction and the need to use this type of poetics stems. The foundations of this type of cognitive and creative procedures should be found in two aspects of the human condition. The first one is certainly the aspiration to discover the sense of everything that man experiences in various ways in the world around him. -

Globalisation and Otherness in the Postcolonial Science Fiction of Ian Mcdonald and Paolo Bacigalupi

Masterscriptie Engelstalige Letterkunde “A Form of Invasive Imagination”: Globalisation and Otherness in the Postcolonial Science Fiction of Ian McDonald and Paolo Bacigalupi Joris van den Hoogen S4375246 Radboud University Nijmegen 20 July 2018 Supervisor: dr. Usha Wilbers ii iii Table of Contents Abstract ......................................................................................................................... iv 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 1 2. Theoretical Framework: Postcolonialism, Hybridity, Globalisation and Science Fiction ............................................................................................................................ 7 2.1 Postcolonialism .................................................................................................. 7 2.2 Hybridity and Globalisation ............................................................................... 8 2.3 Science Fiction: Tropes and Politics ................................................................ 13 2.3.1 Defining Science Fiction.................................................................................. 13 2.3.2 Science Fiction, Difference and the Other .......................................................... 14 2.4 Postcolonial Science Fiction ............................................................................ 16 3. Colonialism, Independence and the Other in Ian McDonald’s Brasyl .................... 20 3.1 Brasyl: -

Getting up to Speed in Science Fiction by Joyce Saricks

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Getting Up To Speed in Science Fiction By Joyce Saricks What is Science Fiction? Science fiction is speculative fiction set in worlds based on plausible scientific theories. The genre traditionally describes future worlds and technologies, but past settings that are nonetheless rich in future technologies have grown in popularity. No matter the time and setting, science supported by known scientific principles drive the stories. What happens in a Science Fiction novel? Science fiction novels run the gamut from traditional action and adventure (with ray guns) to stories that incorporate moral, social, and ethical issues into explorations of philosophical, technical, and intellectual questions. Science fiction is fertile ground for the discussion of challenging and often controversial issues and ideas, and authors may use it expressly for that purpose. Why do people like Science Fiction? The genre is rich in physical and intellectual adventure, with something to please a wide range of readers, from fans of romance and mystery to those who appreciate literary fiction and even westerns. Science fiction is evocative and visual, filled with technical and scientific details. Readers prize science fiction for its ability to raise thought-provoking issues, whether intellectual, moral, or social. Science fiction deals with "why", philosophical speculations, as well as with "where", futuristic settings outside of the usual; with alien beings as well as alien and unorthodox concepts. It cherishes the unexpected, in terms of setting, characters, and plot, and it prides itself in its ability to raise challenging questions. Science fiction also affirms the importance of the imagination and of story in readers' lives. -

Foundation Review of Science Fiction 121 Foundation the International Review of Science Fiction

The InternationalFoundation Review of Science Fiction 121 Foundation The International Review of Science Fiction In this issue: Emma England introduces a special section on diversity in world sf with articles by Garfi eld Benjamin, Christopher Kastensmidt, Lejla Kucukalic, Silvia G. Kurlat Ares, Foundation Gillian Polack and Dale J. Pratt Conference reports by Fran Bigman and Andrea Dietrich, Anna McFarlane, Carolann North and Allan Weiss 44.2 No:121 2015 Vol: Andrew M. Butler investigates the meaning of fun with Eduardo Paolozzi Paul March-Russell explores Africa sf and sf now with Mark Bould and Rhys Williams In addition, there are reviews by: Chelsea Adams, Cherith Baldry, Stephen Baxter, Lucas Boulding, Bodhisattva Chat- topadhyay, Maia Clery, Iain Emsley, Richard Howard, Erik Jaccard, David Seed, Allen Stroud and Michelle K. Yost Of books by: Noga Applebaum, Jack Fennell, Paul Kincaid, Cixin Liu, James Lovegrove, William H. Patterson Jr., Joshua Raulerson, Robert Silverberg, Johanna Sinisalo, Gavin Smith, Ivo Stourton and Peter Szendy Cover image/credit: Sara Al Hazmi, from The Hijab Girl (2014). All rights reserved. Diversity in World SF Foundation is published three times a year by the Science Fiction Foundation (Registered Charity no. 1041052). It is typeset and printed by The Lavenham Press Ltd., 47 Water Street, Lavenham, Suffolk, CO10 9RD. The Foundation Essay Prize 2016 Foundation is a peer-reviewed journal. We are pleased to announce the return of our essay competition. The award is open to all post-graduate research students and to all early career researchers (up to five years Subscription rates for 2015 after the completion of your PhD) who have yet to find a full-time or tenured position. -

Brum Group News Nottingham

NOVACON 41 will be held over the weekend of November 11th to the 13th at The Park Inn, 296 Mansfield Road, Brum Group News Nottingham. NG5 2BT. The Guest of The Monthly Newsletter of the Honour will be SF author JOHN IRMINGHAM CIENCE ICTION ROUP MEANEY. Further details can be found B S F G February 2011 Issue 473 on the website http://novacon.org.uk/ Honorary Presidents: BRIAN W ALDISS, O.B.E. & HARRY HARRISON Committee: Vernon Brown (Chairman); Pat Brown (Treasurer); FUTURE MEETINGS OF THE BSFG Theresa Derwin (Secretary); Rog Peyton (Newsletter Editor); Mar 11th – Fantasy author FRANCES HARDINGE Dave Corby (publicity Officer); William McCabe (Website); April 8th – comic SF/Fantasy author ROBERT RANKIN Vicky Stock (Membership) May 13th - SF author JOHN MEANEY (who will also be Guest of NOVACON 41 Chairman: Steve Lawson Honour at Novacon 41 this year) website: Email: www.birminghamsfgroup.org.uk/ [email protected] June 10th - Happy Birthday BSFG! 40th Anniversary Special Meeting (to be held at the Old Joint Stock) July 15th – SF author and mathematician IAN STEWART th *** PLEASE NOTE CHANGE OF DATE TO FRIDAY 15TH *** Friday 11 February 2011 Aug 12th - SUMMER SOCIAL at the Black Eagle Sep 9th – SF/Fantasy author LIZ WILLIAMS (to be confirmed) ??? THE QUIZ ??? Oct 14th – SF author DAVID WINGROVE author of the Chung Kuo sequence. It’s Quiz time again. Always in February due to the expected bad weather Nov 4th – tba and the risk of speakers being unable to get to Brum – or worse still, the members being unable to get into the city centre. -

Jack Gaughan

3rd ANNUAL SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY FESTIVAL > ♦ * - ' MARCH 23-25 Featuring Discussions and Autographing < Sessions With Top Science-Fiction and a Fantasy Writers & Editors; MON. MARCH 23rd. * 12 PM * POCKET BOOKS PRESENTS: ’David Hartwell (Editor) ‘Brian Aldiss 5:30 7:00 PM DEL REY NIGHT: Featuring ’Lester & Judy-Lynn del Rey (Editors) ’Frederik Pohl ’Stephen R. Donaldson •James White______________ TUES. MARCH 24th. 1-2 PM BERKLEY PUBLISHING PRESENTS: ’Victoria Schochet (Editor) •Charles Platt ’Janet Morris ’Norman Spinrad ’Jill Bauman (llustrator) 5:30 7:00 PM AN EVENING WITH ISAAC ASIMOV “Science Fiction has a Future Too. WED. MARCH 25th. 5:30 7:00 PM DAW BOOKS PRESENTS: ’Donald Wollheim (Editor) ’Lin Carter •Ron Goulart ’C.J. Cherryh ’Doris Piserchia ’John Norman The most recent publication of featured authors will be available for autographing at each event. or visit D. Dolton for o complete schedule 666 Fifth Ave. at 52nd Street 212-247-1740 AMERICA’S FAVORITE BOOK SELLER March 20-22,1981 Writer Guest of Honor JAMES WHITE Artist Guest of Honor JACK GAUGHAN ZOCOZCr 2? Sponsored by The New York Science Fiction Society - The Lunarians, Inc. LUNACON ’81 would like to thank the following people and organizations without whose assistance this convention would not be possible: The Sheraton Heights, Sam Clark, our Honored Guests, Peggy White, Vincent DiFate, Bob Shaw, Joe Orlando, LUNA Publications, certain office machines who have insisted on their anonymity in order to maintain their usefulness to The Cause, Ira Stoller, Roberta Rogow, The Brooklyn Public Library, Dale Hardman, Willie Wilson, Cynthia Levine, D.N.M.S.D., Freff, Oscar Whitfield, Connie Whitfield, Snoopy, Woodstock, Linus, Ruth Gottesman, Smudge, Josephine Sachtcr, Impi,David Sorell, Heather Nachman. -

Sector General by James White Copywrite 1983 Other BOOKS by JAMES WHITE the Secret Visitor

Sector General by James White Copywrite 1983 Other BOOKS BY JAMES WHITE The Secret Visitor (1957) Second Ending (1962) Deadly Litter (1964) Escape Orbit (1965) The Watch Below (1966) All Judgement Fled (1968) The Aliens Among Us (1969) Tomorrow Is Too Far (1971) Dark Inferno (1972) The Dream Millennium (1974) Monsters and Medics (1977) Underkill (1979) Future Past (1982) Federation World (1988) The Silent Stars Go By (1991) The White Papers (1996) Gene Rodden berry's Earth: Final Conflict-The First Protector (Tor, 2000) THE SECTOR GENERAL SERIES Hospital Station (1962) Star Surgeon (1963) Major Operation (1971) Ambulance Ship (1979) Sector General (1983) Star Healer (1985) Code Blue-Emergency (1987) The Genocidal Healer (1992) The Galactic Gourmet (Tor, 1996) Final Diagnosis (Tor, 1997) Mind Changer (br, 1998) Double Contact (br, 1999) Species Classification The Classification System by Gary Louie James White's Sector General stories used a unique four letter classification system that helped describe the species quickly and effectivly, as one would require when the hospitol is a multi species enviroment. Gary Louie was working on a James White concordance. As part of that he completed a classification system, for the sector general series which covers all characters up to Final Diagnosis. This article appeared in the White Papers. Unfortunatly Gary Louie passed away, before the concordance was completed. Classification:AACL Planet:Unknown Species:Crepellian Pet No Individual Names Known A non-intelligent pet kept by AMSOs. It has six python-like ten-tacles which poke though seals in the cloudy plastic of its suit. The tentacles are each at least twenty feet long and tipped with a horny substance which must be steel-hard. -

Stargate Makes Sale! Penny Returning

DECEMBER 1978/JANUARY 1979 NUMBER 20 + +♦■ + ++ + + + +++ ++++++++ + +++++++++++++ +F ++++++++++++++++++++ + + + + + + + + + ++++ ++ +++ + * + + +++ STARGATE MAKES SALE! Stargate. well-known Journal of the ISFA, has finally succeeded in making a sale of part of its work to a foreign SF magazine. The first honours in the inter national market go to ISFA Member Chris O'Connell, whose poem "The Music of the , Universe" has been bought by Brudte Graenser ("Broken Limits") magazine. This publication comes from Denmark; the publisher picked up a copy of Stargate Vol 2, No. 1 (Yellow Cover) at the Convention in Dun Laoghalre last June. The value of the sale is expected to be negligible; nevertheless, we are hopeful that Chris's achievement will mark the beginning of a new trend for ISFA writers of all types. PENNY RETURNING ISFA Member and Alchemist's Head proprietress Penny Cambell is scheduled to return to Dublin on 1 December after a long absence caused by ill health. She has no?/ recovered sufficiently to grace the Essex Street premises once again; there is to be a welcome-back informal reception at Smitty's Restaurent (by the Customs House) on Sunday, J December 1978 at 8 PM. It is doubted that this Newsletter will be out in time to let everyone know in advance, but it was announced at the meeting on 26 November. A good many of the people who attended indicated that they will go to welcome Penny back. +1- ♦• + +++ + •»■++++++++++++++++++++++++++ + +++++++++++ +++++++ +++++ + + + + + + + +++ + + + ++ + +++ + ++ ++ (•++++++ ++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ ++++++++++++++ +++ + ++ +++ UPCOMING MEETINGS +++ +++ +*+ +++ Sunday, 10 December 1978 +++ +++ +++ 444 The ISFA will be putting on a play version of Ray Bradbury's story the +++ 444 Veldt. The cast will consist of volunteer ISFA members, and the direction +++ +v+ will be handled by Robert Lane.