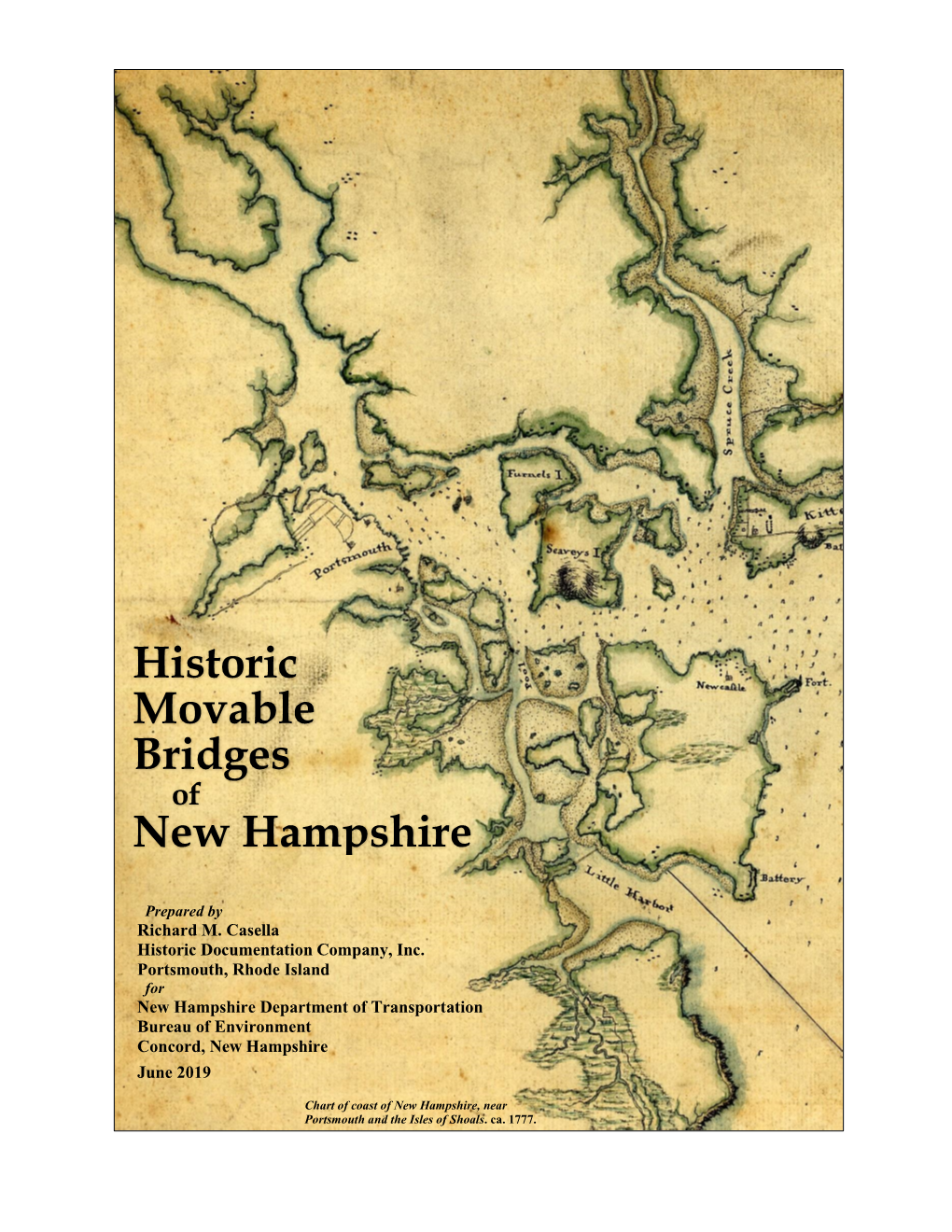

Historic Movable Bridges New Hampshire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timber Bridge History Booklet for Web.Qxp

Printed on Member & recycled Supporter paper TimberTimber TrestleTrestle BridgesBridges inin Alaska Railroad Corporation P.O. Box 107500 • Anchorage, Alaska 99510-7500 (907) 265-2300 • Reservations • (907) 265-2494 AlaskaAlaska RailroadRailroad TTY/TDD • (907) 265-2620 www.AlaskaRailroad.com This History booklet is History also available online by visiting AlaskaRailroad.com Publication Table of Contents “The key to unlocking Alaska is a system of railroads.” — President Woodrow Wilson (1914) The Alaska Railroad at a Glance . 3 Alaska Railroad Historical Overview. 5 Early Development & Operations. 5 Revitalization & World War II . 6 Rehabilitation & Early Cold War . 7 Recent History . 7 About Timber Trestle Bridges . 8 History of Timber Trestle Bridges . 10 in the United States History of Timber Trestle Bridges . 13 on the Alaska Railroad Bridge under constructon at MP 54. (ARRC photo archive) Status of Timber Trestle Bridges . 18 on the Alaska Railroad Historical Significance of Alaska . … progress was immediately hindered 20 Railroad Timber Trestle Bridges by numerous water crossings and abundant muskeg. Representative ARR Timber Bridges . 20 Because a trestle was the easiest and cheapest way to negotiate these barriers, a great many of them were erected, Publication Credits . 22 only to be later replaced or Research Acknowledgements . 22 filled and then forgotten. — Alaska Engineering Commission (1915) Bibliography of References . 22 Cover photo: A train leaves Anchorage, crossing Ship Creek Bridge in 1922. (ARRC photo archive) 01 The Alaska Railroad at a Glance early a century ago, President Woodrow Wilson charged the Alaskan Engineering Commission with building a railroad connecting a southern ice-free harbor to the territory’s interior in order to open this vast area to commerce. -

Interstate Bridge Replacement Program December 2019 Progress Report

Interstate Bridge Replacement Program December 2019 Progress Report December 2019 Progress Report i This page intentionally left blank. ii Interstate Bridge Replacement Program December 2, 2019 (Electronic Transmittal Only) The Honorable Governor Inslee The Honorable Kate Brown WA Senate Transportation Committee Oregon Transportation Commission WA House Transportation Committee OR Joint Committee on Transportation Dear Governors, Transportation Commission, and Transportation Committees: On behalf of the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) and the Oregon Department of Transportation (ODOT), we are pleased to submit the Interstate Bridge Replacement Program status report, as directed by Washington’s 2019-21 transportation budget ESHB 1160, section 306 (24)(e)(iii). The intent of this report is to share activities that have lead up to the beginning of the biennium, accomplishments of the program since funding was made available, and future steps to be completed by the program as it moves forward with the clear support of both states. With the appropriation of $35 million in ESHB 1160 to open a project office and restart work to replace the Interstate Bridge, Governor Inslee and the Washington State Legislature acknowledged the need to renew efforts for replacement of this aging infrastructure. Governor Kate Brown and the Oregon Transportation Commission (OTC) directed ODOT to coordinate with WSDOT on the establishment of a project office. The OTC also allocated $9 million as the state’s initial contribution, and Oregon Legislative leadership appointed members to a Joint Committee on the Interstate Bridge. These actions demonstrate Oregon’s agreement that replacement of the Interstate 5 Bridge is vital. As is conveyed in this report, the program office is working to set this project up for success by working with key partners to build the foundation as we move forward toward project development. -

16817.00 NHDOT PIN: PK 13678E Prepared by (Name/F

Project Name: ME-NH Connections Study FHWA No: PR-1681(700X) MaineDOT PIN: 16817.00 NHDOT PIN: PK 13678E Prepared by (Name/Firm): Lauren Meek, P.E., HNTB Contract Number: 20090325000000005165 Technical Memorandum No.: 3 - Navigational Needs of the Piscataqua River Date (month/year): August, 2009 Subject: Navigational Data for the Sarah Mildred Long and Portsmouth Memorial Bridges Background This Tech Memo is a supplement to a 2006 HNTB memo that identified issues and preferences for users of the Piscataqua River during the rehabilitation of the Portsmouth Memorial Bridge based on a mail-back navigational survey. This 2006 memo is attached as Appendix A. Purpose The purpose of this memorandum is to: a.) summarize the existing horizontal and vertical clearances and identify the minimum required bridge lifts versus the actual number of bridge lifts of the Sarah Mildred Long and Portsmouth Memorial Bridges; b.) identify the users of the river; c.) analyze the bridge lift records; d.) summarize feedback from users of the river and those responsible for the river’s operation. Additionally, a survey to address the current and future uses has been sent to users of the river. A separate technical memorandum will be prepared with the analysis of the responses when received. 1 Methodology a. Existing Clearances and Frequency of Lifts Table 1 provides the clearances for the three lower Piscataqua River bridges as identified on the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Chart 13283, 20th Edition. The vertical clearance is the distance between mean high water and the underside of the bridge. The Portsmouth Memorial and Sarah Mildred Long Bridges have lift spans that provide additional vertical clearance when opened. -

"Smackdown on the Hudson" the Patroon, the West India Company, and the Founding of Albany

"Smackdown on the Hudson" The Patroon, the West India Company, and the Founding of Albany Lesson Procedures Essential question: How was the colony of New Netherland ruled by the Dutch West India Company and the patroons? Grade 7 Content Understandings, New York State Standards: Social Studies Standards This lesson covers European Exploration and Colonization of the Americas and Life in Colonial Communities, focusing on settlement patterns and political life in New Netherland. By studying the conflict between the Petrus Stuyvesant and the Brant van Slichtenhorst, students will consider the sources of historic documents and evaluate their reliability. Common Core Standards: Reading Standards By analyzing historic documents, students will develop essential reading, writing, and critical thinking skills. They will read and analyze informational texts and draw inferences from those texts. Students will explain what happened and why based on information from the readings. Additionally, as a class, students will discuss general academic and domain- specific words or phrases relevant to the unit. Speaking and Listening Standards Students will engage in group and teacher-led collaborative discussions, using textual evidence to pose hypotheses and respond to specific questions. They will also report to the class on their group’s assigned topic, explaining their ideas, analyses, and observations and citing reasons and evidence to support their claims. New Netherland Institute New Netherland Research Center "Smackdown on the Hudson" 2 Writing Standards To conclude this lesson, students write a letter to the editor of the Rensselaerwijck Times that draws evidence from informational texts and supports claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence. Historical Context: In 1614, soon after the founding of the New Netherland Company (predecessor to the West India Company, est. -

A-Brief-History-Of-The-Mohican-Nation

wig d r r ksc i i caln sr v a ar ; ny s' k , a u A Evict t:k A Mitfsorgo 4 oiwcan V 5to cLk rid;Mc-u n,5 3 ss l Y gew y » w a. 3 k lz x OWE u, 9g z ca , Z 1 9 A J i NEI x i c x Rat 44MMA Y t6 manY 1 YryS y Y s 4 INK S W6 a r sue`+ r1i 3 My personal thanks gc'lo thc, f'al ca ° iaag, t(")mcilal a r of the Stockbridge-IMtarasee historical C;orrunittee for their comments and suggestions to iatataraare tlac=laistcatic: aal aac c aracy of this brief' history of our people ta°a Raa la€' t "din as for her c<arefaal editing of this text to Jeff vcic.'of, the rlohican ?'yews, otar nation s newspaper 0 to Chad Miller c d tlac" Land Resource aM anaagenient Office for preparing the map Dorothy Davids, Chair Stockbridge -Munsee Historical Committee Tke Muk-con-oLke-ne- rfie People of the Waters that Are Never Still have a rich and illustrious history which has been retrained through oral tradition and the written word, Our many moves frorn the East to Wisconsin left Many Trails to retrace in search of our history. Maanv'rrails is air original design created and designed by Edwin Martin, a Mohican Indian, symbol- izing endurance, strength and hope. From a long suffering proud and deternuned people. e' aw rtaftv f h s is an aatathCutic basket painting by Stockbridge Mohican/ basket weavers. -

Columbia River I-5 Bridge Planning Inventory Report

Report to the Washington State Legislature Columbia River I-5 Bridge Planning Inventory December 2017 Columbia River I-5 Bridge Planning Inventory Errata The Columbia River I-5 Bridge Planning Inventory published to WSDOT’s website on December 1, 2017 contained the following errata. The items below have been corrected in versions downloaded or printed after January 10, 2018. Section 4, page 62: Corrects the parties to the tolling agreement between the States—the Washington State Transportation Commission and the Oregon Transportation Commission. Miscellaneous sections and pages: Minor grammatical corrections. Columbia River I-5 Bridge Planning Inventory | December 2017 Table of Contents Executive Summary. .1 Section 1: Introduction. .29 Legislative Background to this Report Purpose and Structure of this Report Significant Characteristics of the Project Area Prior Work Summary Section 2: Long-Range Planning . .35 Introduction Bi-State Transportation Committee Portland/Vancouver I-5 Transportation and Trade Partnership Task Force The Transition from Long-Range Planning to Project Development Section 3: Context and Constraints . 41 Introduction Guiding Principles: Vision and Values Statement & Statement of Purpose and Need Built and Natural Environment Navigation and Aviation Protected Species and Resources Traffic Conditions and Travel Demand Safety of Bridge and Highway Facilities Freight Mobility Mobility for Transit, Pedestrian and Bicycle Travel Section 4: Funding and Finance. 55 Introduction Funding and Finance Plan Evolution During -

Designation of Critical Habitat for the Gulf of Maine, New York Bight, And

Federal Register / Vol. 81, No. 107 / Friday, June 3, 2016 / Proposed Rules 35701 the Act, including the factors identified Recovery and State Grants, Ecological Public hearings and public in this finding and explanation (see Services Program, U.S. Fish and information meetings: We will hold two Request for Information, above). Wildlife Service. public hearings and two public informational meetings on this proposed Conclusion Authority rule. We will hold a public On the basis of our evaluation of the The authority for these actions is the informational meeting from 2 to 4 p.m., information presented under section Endangered Species Act of 1973, as in Annapolis, Maryland on Wednesday, 4(b)(3)(A) of the Act, we have amended (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.). July 13 (see ADDRESSES). A second determined that the petition to remove Dated: May 25, 2016. public informational meeting will be the golden-cheeked warbler from the Stephen Guertin, held from 3 to 5 p.m., in Portland, List of Endangered and Threatened Maine on Monday, July 18 (see Wildlife does not present substantial Acting Director, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. ADDRESSES). We will hold two public scientific or commercial information [FR Doc. 2016–13120 Filed 6–2–16; 8:45 am] hearings, from 3 to 5 p.m. and 6 to 8 indicating that the requested action may p.m., in Gloucester, Massachusetts on BILLING CODE 4333–15–P be warranted. Therefore, we are not Thursday, July 21 (see ADDRESSES). initiating a status review for this ADDRESSES: You may submit comments, species. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE identified by the NOAA–NMFS–2015– We have further determined that the 0107, by either of the following petition to list the U.S. -

Official List of Public Waters

Official List of Public Waters New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Water Division Dam Bureau 29 Hazen Drive PO Box 95 Concord, NH 03302-0095 (603) 271-3406 https://www.des.nh.gov NH Official List of Public Waters Revision Date October 9, 2020 Robert R. Scott, Commissioner Thomas E. O’Donovan, Division Director OFFICIAL LIST OF PUBLIC WATERS Published Pursuant to RSA 271:20 II (effective June 26, 1990) IMPORTANT NOTE: Do not use this list for determining water bodies that are subject to the Comprehensive Shoreland Protection Act (CSPA). The CSPA list is available on the NHDES website. Public waters in New Hampshire are prescribed by common law as great ponds (natural waterbodies of 10 acres or more in size), public rivers and streams, and tidal waters. These common law public waters are held by the State in trust for the people of New Hampshire. The State holds the land underlying great ponds and tidal waters (including tidal rivers) in trust for the people of New Hampshire. Generally, but with some exceptions, private property owners hold title to the land underlying freshwater rivers and streams, and the State has an easement over this land for public purposes. Several New Hampshire statutes further define public waters as including artificial impoundments 10 acres or more in size, solely for the purpose of applying specific statutes. Most artificial impoundments were created by the construction of a dam, but some were created by actions such as dredging or as a result of urbanization (usually due to the effect of road crossings obstructing flow and increased runoff from the surrounding area). -

Rainbow Smelt Spawning Monitoring

PROGRESS REPORT State: NEW HAMPSHIRE Grant: F-61-R-22/F19AF00061 Grant Title: NEW HAMPSHIRE’S MARINE FISHERIES INVESTIGATIONS Project I: DIADROMOUS FISH INVESTIGATIONS Job 2: MONITORING OF RAINBOW SMELT SPAWNING ACTIVITY Objective: To annually monitor the Rainbow Smelt Osmerus mordax resource using fishery independent techniques during their spawning run in the Great Bay Estuary. Period Covered: January 1, 2019 - December 31, 2019 ABSTRACT In 2019, a total of 844 Rainbow Smelt Osmerus mordax (349 in Oyster River, 405 in Winnicut River, and 90 in Squamscott River) were caught in fyke nets. The CPUE in 2019 was highest in the Oyster River with 23.79 smelt per day, whereas the Winnicut River (8.46 smelt per day) and Squamscott River (5.54 smelt per day) were lower. A male-skewed sex ratio was observed at all rivers, a likely result of differences in spawning behavior between sexes. The age distribution of captured Rainbow Smelt, weighted by total catch was highest for age-2 fish, followed by age-1, age-3, and age-4 fish. Most water quality measurements (temperature, dissolved oxygen, specific conductivity, and pH) were within or near acceptable ranges for smelt spawning and egg incubation and development in 2019; however, turbidity was above the threshold in the Oyster River for most days monitored. INTRODUCTION Rainbow Smelt Osmerus mordax are small anadromous fish that live in nearshore coastal waters and spawn in the spring in tidal rivers immediately above the head of tide in freshwater (Kendall 1926; Murawski et al. 1980; Buckley 1989). Anadromous smelt serve as important prey for commercial and recreational culturally valuable species, such as Atlantic Cod Gadus morhua, Atlantic Salmon Salmo salar, and Striped Bass Morone saxatilis (Clayton et al. -

Exeter Road Bridge (NHDOT Bridge 162/142)

Exeter Road Bridge (NHDOT Bridge 162/142) New Hampshire Historic Property Documentation An historical study of the railroad overpass on Exeter Road near the center of Hampton. Preservation Company 5 Hobbs Road Kensington, N.H. 2004 NEW HAMPSHIRE HISTORIC PROPERTY DOCUMENTATION EXETER ROAD BRIDGE (NHDOT Bridge 162/142) NH STATE NO. 608 Location: Eastern Railroad/Boston and Maine Eastern Division at Exeter Road in Hampton, New Hampshire (Milepost 46.59), Rockingham County Date of Construction: Abutments 1900; bridge reconstructed ca. 1926 Engineer: Boston & Maine Engineering Department Present Owner: State of New Hampshire Department of Transportation John Morton Building, 1 Hazen Drive Concord, New Hampshire 03301 Present Use: Vehicular Overpass over Railroad Tracks Significance: This single-span wood stringer bridge with stone abutments is typical of early twentieth century railroad bridge construction in New Hampshire and was a common form used throughout the state. The crossing has been at the same site since the railroad first came through the area in 1840 and was the site of dense commercial development. The overpass and stone abutments date to 1900 when the previous at-grade crossing was eliminated. The construction of the bridge required the wholesale shifting of Hampton Village's commercial center to its current location along Route 1/Lafayette Road. Project Information: This narrative was prepared beginning in 2004, to accompany a series of black-and-white photographs taken by Charley Freiberg in August 2004 to record the Exeter Road Bridge. The bridge is located on, and a contributing element to, the Eastern Railroad Historic District, which was determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places under Criterion A, and C as a linear transportation district on May 3, 2002. -

HISTORIC RESOURCES CHAPTER 2015 REGIONAL MASTER PLAN for the Rockingham Planning Commission Region

HISTORIC RESOURCES CHAPTER 2015 REGIONAL MASTER PLAN For the Rockingham Planning Commission Region Rockingham Planning Commission Regional Master Plan Historical Resources C ONTENTS Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 What the Region Said About Historical Resources ............................................................................ 2 Historical Resources Goals ............................................................................................................... 3 Existing Conditions ........................................................................................................................... 5 Historical Background and Resources in the RPC Region....................................................................... 5 Preservation Tools .......................................................................................................................... 9 Key Issues and Challenges ............................................................................................................. 18 What Do We Preserve? ................................................................................................................. 18 Education and Awareness .............................................................................................................. 19 Redevelopment, Densification, and Tear-Downs ................................................................................ 20 -

A Technical Characterization of Estuarine and Coastal New Hampshire New Hampshire Estuaries Project

AR-293 University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository PREP Publications Piscataqua Region Estuaries Partnership 2000 A Technical Characterization of Estuarine and Coastal New Hampshire New Hampshire Estuaries Project Stephen H. Jones University of New Hampshire Follow this and additional works at: http://scholars.unh.edu/prep Part of the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation New Hampshire Estuaries Project and Jones, Stephen H., "A Technical Characterization of Estuarine and Coastal New Hampshire" (2000). PREP Publications. Paper 294. http://scholars.unh.edu/prep/294 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Piscataqua Region Estuaries Partnership at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in PREP Publications by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Technical Characterization of Estuarine and Coastal New Hampshire Published by the New Hampshire Estuaries Project Edited by Dr. Stephen H. Jones Jackson estuarine Laboratory, university of New Hampshire Durham, NH 2000 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................i LIST OF TABLES ....................................................................................................vi LIST OF FIGURES.................................................................................................viii