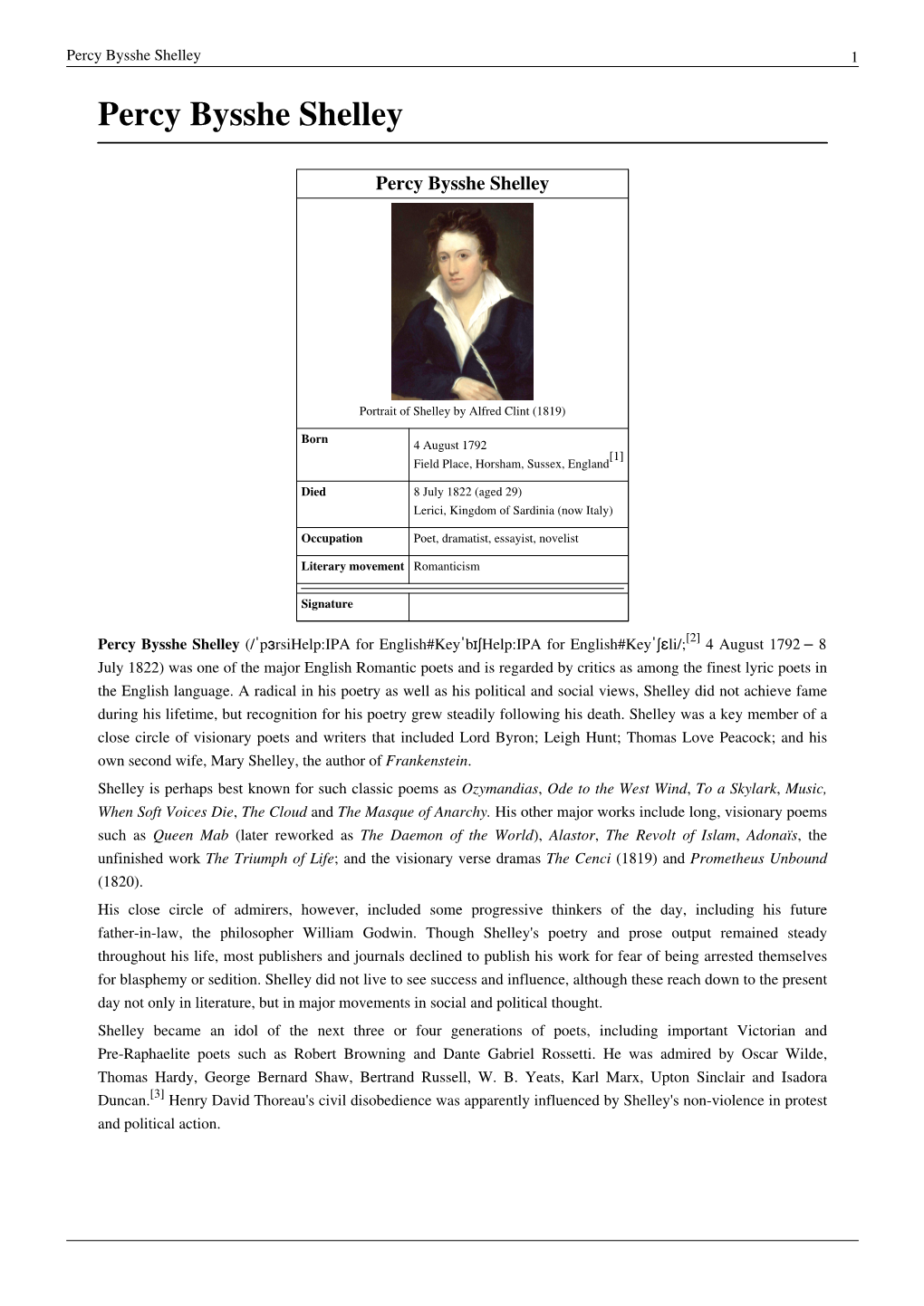

Percy Bysshe Shelley 1 Percy Bysshe Shelley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Byron's Romantic Adventures in Spain

1 BYRON’S ROMANTIC ADVENTURES IN SPAIN RICHARD A. CARDWELL UNIVERSITY OF NOTTINGHAM I On the July 2nd 1809, after several delays with the weather, Byron set off from Falmouth on the Lisbon Packet, The Princess Elizabeth , on his Grand Tour of the Mediterranean world not controlled by France. Four and a half days later he landed in Lisbon. From there, across a war-ravaged Portugal and Spain, he headed on horseback to Seville and Cádiz, accompanied by Hobhouse, details recorded in the latter’s diary. But we know little of Byron’s stay in Seville and Cádiz save what he relates in a letter to his mother, Catherine Byron, from Gibraltar dated August 11th 1809. It is ironic that Byron never saw her in life again. The first part of the letter reads as follows: Seville is a beautiful town, though the streets are narrow they are clean, we lodged in the house of two Spanish unmarried ladies, who possess six houses in Seville, and gave me a curious specimen of Spanish manners. They are women of character, and the eldest a fine woman, the youngest pretty but not so good a figure as Donna Josepha, the freedom of woman which is general here astonished me not a little, and in the course of further observation I find that reserve is not the characteristic of the Spanish belles, who are on general very handsome, with large black eyes, and very fine forms. – The eldest honoured your unworthy son with very particular attention, embracing him with great tenderness at parting (I was there but three days) after cutting off a lock of his hair, & presenting him with one of her own about three feet in length, which I send, and beg you will retain till my return. -

![Premature and Dissolving Endings in Shelley's Poetry Author[S]: Julia Tejblum Source: Moveabletype, Vol](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1891/premature-and-dissolving-endings-in-shelleys-poetry-author-s-julia-tejblum-source-moveabletype-vol-101891.webp)

Premature and Dissolving Endings in Shelley's Poetry Author[S]: Julia Tejblum Source: Moveabletype, Vol

Article: The Fisher, The Spear, and the Fortunate Fish: Premature and Dissolving Endings in Shelley's Poetry Author[s]: Julia Tejblum Source: MoveableType, Vol. 7, ‘Intersections’ (2014) DOI: 10.14324/111.1755-4527.059 MoveableType is a Graduate, Peer-Reviewed Journal based in the Department of English at UCL. © 2014 Julia Tejblum. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY) 4.0https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. The Fisher, the Spear, and the Fortunate Fish: Premature and Dissolving Endings in Shelley’s Poetry Walter Benjamin famously o served that our interest in narrative is bound up not only with our in" terest in life, but, more tellingly, with our interest in death: we hope to learn something of the meaning of our o!n lives from the lives of fctional chara$ters, but mu$h of that meaning is revealed to us only through our witnessing the chara$ter’s death% The revelation of meaning through death, which Ben" jamin likens to cat$hing the heat of a fame, is impossi le without fction, sin$e none of us survives our o!n death and, therefore, none can ta&e part in the revelation unless it is at the e(pense of another: )What dra!s the reader to the novel is the hope of warming his shivering life with a death he reads a out%*+ But Benjamin’s o servations go beyond the sphere of the novel; a curiosity a out any narrative ending is a curiosity -

Select Letters of Percy Bysshe Shelley

ENGLISH CLÀSSICS The vignette, representing Shelleÿs house at Great Mar lou) before the late alterations, is /ro m a water- colour drawing by Dina Williams, daughter of Shelleÿs friend Edward Williams, given to the E ditor by / . Bertrand Payne, Esq., and probably made about 1840. SELECT LETTERS OF PERCY BYSSHE SHELLEY EDITED WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY RICHARD GARNETT NEW YORK D.APPLETON AND COMPANY X, 3, AND 5 BOND STREET MDCCCLXXXIII INTRODUCTION T he publication of a book in the series of which this little volume forms part, implies a claim on its behalf to a perfe&ion of form, as well as an attradiveness of subjeâ:, entitling it to the rank of a recognised English classic. This pretensión can rarely be advanced in favour of familiar letters, written in haste for the information or entertain ment of private friends. Such letters are frequently among the most delightful of literary compositions, but the stamp of absolute literary perfe&ion is rarely impressed upon them. The exceptions to this rule, in English literature at least, occur principally in the epistolary litera ture of the eighteenth century. Pope and Gray, artificial in their poetry, were not less artificial in genius to Cowper and Gray ; but would their un- their correspondence ; but while in the former premeditated utterances, from a literary point of department of composition they strove to display view, compare with the artifice of their prede their art, in the latter their no less successful cessors? The answer is not doubtful. Byron, endeavour was to conceal it. Together with Scott, and Kcats are excellent letter-writers, but Cowper and Walpole, they achieved the feat of their letters are far from possessing the classical imparting a literary value to ordinary topics by impress which they communicated to their poetry. -

Turkish Tales” – the Siege of Corinth and Parisina – Were Still to Come

1 THE CORSAIR and LARA These two poems may make a pair: Byron’s note to that effect, at the start of Lara, leaves the question to the reader. I have put them together to test the thesis. Quite apart from the discrepancy between the heroine’s hair-colour (first pointed out by E.H.Coleridge) it seems to me that the protagonists are different men, and that to see the later poem as a sequel to and political development of the earlier, is not of much use in understanding either. Lara is a man of uncontrollable violence, unlike Conrad, whose propensity towards gentlemanly self-government is one of two qualities (the other being his military incompetence) which militates against the convincing depiction of his buccaneer’s calling. Conrad, offered rescue by Gulnare, almost turns it down – and is horrified when Gulnare murders Seyd with a view to easing his escape. On the other hand, Lara, astride the fallen Otho (Lara, 723-31) would happily finish him off. Henry James has a dialogue in which it is imagined what George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda would do, once he got to the Holy Land.1 The conclusion is that he’d drink lots of tea. I’m working at an alternative ending to Götterdämmerung, in which Brunnhilde accompanies Siegfried on his Rheinfahrt, sees through Gunther and Gutrune at once, poisons Hagen, and gets bored with Siegfried, who goes off to be a forest warden while she settles down in bed with Loge, because he’s clever and amusing.2 By the same token, I think that Gulnare would become irritated with Conrad, whose passivity and lack of masculinity she’d find trying. -

DID JOSHUA REYNOLDS PAINT HIS PICTURES? Matthew C

DID JOSHUA REYNOLDS PAINT HIS PICTURES? Matthew C. Hunter Did Joshua Reynolds Paint His Pictures? The Transatlantic Work of Picturing in an Age of Chymical Reproduction In the spring of 1787, King George III visited the Royal Academy of Arts at Somerset House on the Strand in London’s West End. The king had come to see the first series of the Seven Sacraments painted by Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665) for Roman patron Cassiano dal Pozzo in the later 1630s. It was Poussin’s Extreme Unction (ca. 1638–1640) (fig. 1) that won the king’s particular praise.1 Below a coffered ceiling, Poussin depicts two trains of mourners converging in a darkened interior as a priest administers last rites to the dying man recumbent on a low bed. Light enters from the left in the elongated taper borne by a barefoot acolyte in a flowing, scarlet robe. It filters in peristaltic motion along the back wall where a projecting, circular molding describes somber totality. Ritual fluids proceed from the right, passing in relay from the cerulean pitcher on the illuminated tripod table to a green-garbed youth then to the gold flagon for which the central bearded elder reaches, to be rubbed as oily film on the invalid’s eyelids. Secured for twenty-first century eyes through a spectacular fund-raising campaign in 2013 by Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum, Poussin’s picture had been put before the king in the 1780s by no less spirited means. Working for Charles Manners, fourth Duke of Rutland, a Scottish antiquarian named James Byres had Poussin’s Joshua Reynolds, Sacraments exported from Rome and shipped to London where they Diana (Sackville), Viscountess Crosbie were cleaned and exhibited under the auspices of Royal Academy (detail, see fig. -

National Trauma and Romantic Illusions in Percy Shelley's the Cenci

humanities Article National Trauma and Romantic Illusions in Percy Shelley’s The Cenci Lisa Kasmer Department of English, Clark University, Worcester, MA 01610, USA; [email protected] Received: 18 March 2019; Accepted: 8 May 2019; Published: 14 May 2019 Abstract: Percy Shelley responded to the 1819 Peterloo Massacre by declaring the government’s response “a bloody murderous oppression.” As Shelley’s language suggests, this was a seminal event in the socially conscious life of the poet. Thereafter, Shelley devoted much of his writing to delineating the sociopolitical milieu of 1819 in political and confrontational works, including The Cenci, a verse drama that I argue portrays the coercive violence implicit in nationalism, or, as I term it, national trauma. In displaying the historical Roman Cenci family in starkly vituperous manner, that is, Shelley reveals his drive to speak to the historical moment, as he creates parallels between the tyranny that the Roman pater familias exhibits toward his family and the repression occurring during the time of emergent nationhood in Hanoverian England, which numerous scholars have addressed. While scholars have noted discrete acts of trauma in The Cenci and other Romantic works, there has been little sustained criticism from the theoretical point of view of trauma theory, which inhabits the intersections of history, cultural memory, and trauma, and which I explore as national trauma. Through The Cenci, Shelley implies that national trauma inheres within British nationhood in the multiple traumas of tyrannical rule, shored up by the nation’s cultural memory and history, instantiated in oppressive ancestral order and patrilineage. Viewing The Cenci from the perspective of national trauma, however, I conclude that Shelley’s revulsion at coercive governance and nationalism loses itself in the contemplation of the beautiful pathos of the effects of national trauma witnessed in Beatrice, as he instead turns to a more traditional national narrative. -

Grosvenor Prints 19 Shelton Street Covent Garden London WC2H 9JN

Grosvenor Prints 19 Shelton Street Covent Garden London WC2H 9JN Tel: 020 7836 1979 Fax: 020 7379 6695 E-mail: [email protected] www.grosvenorprints.com Dealers in Antique Prints & Books Prints from the Collection of the Hon. Christopher Lennox-Boyd Arts 3801 [Little Fatima.] [Painted by Frederick, Lord Leighton.] Gerald 2566 Robinson Crusoe Reading the Bible to Robinson. London Published December 15th 1898 by his Man Friday. "During the long timer Arthur Lucas the Proprietor, 31 New Bond Street, W. Mezzotint, proof signed by the engraver, ltd to 275. that Friday had now been with me, and 310 x 490mm. £420 that he began to speak to me, and 'Little Fatima' has an added interest because of its understand me. I was not wanting to lay a Orientalism. Leighton first showed an Oriental subject, foundation of religious knowledge in his a `Reminiscence of Algiers' at the Society of British mind _ He listened with great attention." Artists in 1858. Ten years later, in 1868, he made a Painted by Alexr. Fraser. Engraved by Charles G. journey to Egypt and in the autumn of 1873 he worked Lewis. London, Published Octr. 15, 1836 by Henry in Damascus where he made many studies and where Graves & Co., Printsellers to the King, 6 Pall Mall. he probably gained the inspiration for the present work. vignette of a shipwreck in margin below image. Gerald Philip Robinson (printmaker; 1858 - Mixed-method, mezzotint with remarques showing the 1942)Mostly declared pirnts PSA. wreck of his ship. 640 x 515mm. Tears in bottom Printsellers:Vol.II: margins affecting the plate mark. -

Gender, Authorship and Male Domination: Mary Shelley's Limited

CHAPITRE DE LIVRE « Gender, Authorship and Male Domination: Mary Shelley’s Limited Freedom in ‘‘Frankenstein’’ and ‘‘The Last Man’’ » Michael E. Sinatra dans Mary Shelley's Fictions: From Frankenstein to Falkner, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2000, p. 95-108. Pour citer ce chapitre : SINATRA, Michael E., « Gender, Authorship and Male Domination: Mary Shelley’s Limited Freedom in ‘‘Frankenstein’’ and ‘‘The Last Man’’ », dans Michael E. Sinatra (dir.), Mary Shelley's Fictions: From Frankenstein to Falkner, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2000, p. 95-108. 94 Gender cal means of achievement ... Castruccio will unite in himself the lion and the fox'. 13. Anne Mellor in Ruoff, p. 284. 6 14. Shelley read the first in May and the second in June 1820. She also read Julie, 011 la Nouvelle Héloïse (1761) for the third time in February 1820, Gender, Authorship and Male having previously read it in 1815 and 1817. A long tradition of educated female poets, novelists, and dramatists of sensibility extending back to Domination: Mary Shelley's Charlotte Smith and Hannah Cowley in the 1780s also lies behind the figure of the rational, feeling female in Shelley, who read Smith in 1816 limited Freedom in Frankenstein and 1818 (MWS/ 1, pp. 318-20, Il, pp. 670, 676). 15. On the entrenchment of 'conservative nostalgia for a Burkean mode] of a and The Last Man naturally evolving organic society' in the 1820s, see Clemit, The Godwinian Novel, p. 177; and Elie Halévy, The Liberal Awakening, 1815-1830, trans. E. Michael Eberle-Sinatra 1. Watkin (New York: Barnes & Noble, 1961) pp. 128-32. -

Anthology of Polish Poetry. Fulbright-Hays Summer Seminars Abroad Program, 1998 (Hungary/Poland)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 444 900 SO 031 309 AUTHOR Smith, Thomas A. TITLE Anthology of Polish Poetry. Fulbright-Hays Summer Seminars Abroad Program, 1998 (Hungary/Poland). INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 206p. PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020)-- Guides Classroom - Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Anthologies; Cultural Context; *Cultural Enrichment; *Curriculum Development; Foreign Countries; High Schools; *Poetry; *Poets; Polish Americans; *Polish Literature; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Poland; Polish People ABSTRACT This anthology, of more than 225 short poems by Polish authors, was created to be used in world literature classes in a high school with many first-generation Polish students. The following poets are represented in the anthology: Jan Kochanowski; Franciszek Dionizy Kniaznin; Elzbieta Druzbacka; Antoni Malczewski; Adam Mickiewicz; Juliusz Slowacki; Cyprian Norwid; Wladyslaw Syrokomla; Maria Konopnicka; Jan Kasprowicz; Antoni Lange; Leopold Staff; Boleslaw Lesmian; Julian Tuwim; Jaroslaw Iwaszkiewicz; Maria Pawlikowska; Kazimiera Illakowicz; Antoni Slonimski; Jan Lechon; Konstanty Ildefons Galczynski; Kazimierz Wierzynski; Aleksander Wat; Mieczyslaw Jastrun; Tymoteusz Karpowicz; Zbigniew Herbert; Bogdan Czaykowski; Stanislaw Baranczak; Anna Swirszczynska; Jerzy Ficowski; Janos Pilinsky; Adam Wazyk; Jan Twardowski; Anna Kamienska; Artur Miedzyrzecki; Wiktor Woroszlyski; Urszula Koziol; Ernest Bryll; Leszek A. Moczulski; Julian Kornhauser; Bronislaw Maj; Adam Zagajewskii Ferdous Shahbaz-Adel; Tadeusz Rozewicz; Ewa Lipska; Aleksander Jurewicz; Jan Polkowski; Ryszard Grzyb; Zbigniew Machej; Krzysztof Koehler; Jacek Podsiadlo; Marzena Broda; Czeslaw Milosz; and Wislawa Szymborska. (BT) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. Anthology of Polish Poetry. Fulbright Hays Summer Seminar Abroad Program 1998 (Hungary/Poland) Smith, Thomas A. -

Shelley's Hellas and the Mask of Anarchy Are Thematically, Linguistically

63 Percy Bysshe Shelley, the Newspapers of 1819 and the Language of Poetry Catherine Boyle This essay rediscovers the link between the expatriate newspaper Gali- gnani’s Messenger and Shelley’s 1819 political poetry, particularly The Mask of Anarchy and Song, To the Men of England. It is suggested that a reading of this newspaper helps us to understand Shelley’s response to the counter-revolutionary press of his day; previous accounts have tended to solely stress Shelley’s allegiance to Leigh Hunt’s politics. As well as being a contribution to book history, this essay highlights the future of the nine - teenth-century book by exploring the ways the ongoing digitization of nine - teenth-century texts can enable new readings of familiar texts. It also covers some theoretical issues raised by these readings, namely the development of the Digital Humanities and intertextual theory. I must trespass upon the forgiveness of my readers for the display of newspaper erudition to which I have been reduced. Percy Bysshe Shelley, Preface to Hellas, 1821 1 helley’s Hellas and The Mask of Anarchy are thematically, linguistically, and compositionally related , and these resemblances can lead into a close S reading of Shelley’s 1819 political poetry. Both feature revolutions: an actual Greek revolution that had already occurred, and the putative revolution after the events of the Peterloo Massacre in 1819. Both mythologize historical events. In Hellas , the figure of the Jew Ahasuerus, doomed to wander the earth eternally, appears amidst an account of historical events. In The Mask of Anarchy Shelley inserts an apocalyptic, ungendered Shape which enacts the downfall of Anarchy. -

Venice According… Venice According to Odyniec (And Mickiewicz?) in Romantic Contexts

Czytanie Literatury https://doi.org/10.18778/2299-7458.09.04 Łódzkie Studia Literaturoznawcze 9/2020 ISSN 2299–7458 ANNA KURSKA e-ISSN 2449–8386 Jan Kochanowski University of Kielce 0000-0002-2776-2449 65 VeNICe ACCoRDING… VeNICe Venice According to Odyniec (and Mickiewicz?) in Romantic Contexts SUMMARY This text is a reconstruction of the image of Venice offered in Listy z podróży by Antoni Edward Odyniec. Against the background of Romantic traditions (Byron, Chateaubriand, Shelley, and Radcliffe), I present how the author shaped the portrait of Venice suspended between the Romantic vision of the city/monster (Leviathan) and the ballad-based vision of the city/Siren. I indicate not only the fact that the im- age of Venice was rooted in the sentimental/Romantic stereotype, but I also define to what extent it was formed by the imagined world of Polish nobility, i.e. szlachta. Most of all, however, I am interested in the traces present in Listy z podróży which enable one to uncover Mickiewicz’s influence on how Odyniec shaped the image of Venice. Keywords Adam Mickiewicz, Antoni Edward Odyniec, Venice, Romanticism, journey. Mickiewicz arrived with Odyniec in Venice on 7 October 1829 “at one in the afternoon”; they stayed at the de Luna Inn, from where they moved the very next day to a private apartment at “Ponte dei Dai, Torre Correnta, al. Moro.” Their visit lasted until 20 October and it was recorded by Antoni Edward Odyniec in a fragment of Listy z podróży that he wrote to Julian Korsak and Ignacy Chodźko. His description raises a major question: to what degree © by the author, licensee Łódź University – Łódź University Press, Łódź, Poland. -

Bloody Poetry: on the Role of Medicine in John Keats's Life and Art

Caroline Bertonèche, On the Role of Medicine in John Keat’s Life and Art Bloody Poetry: On the Role of Medicine in JoHn Keats's Life and Art Caroline Bertonèche To see Keats only as yet another British Romantic poet, author of the odes and the Hyperions, who died in exile, after one last fit of tuberculosis, is to forget that he spent as many years – six years to be precise – of his short life studying medicine as he did writing poetry. First a young apprentice to an apothecary, then a medical student from 1811 to 1816, Keats chose to start his career as an artist without completely burying his scientific past, making sure never to get rid of his old books on medicine – these books that were to previously shape his intellect before he even started putting together his collections of poems. Satisfied to have had the ability to distance himself from a rather contrasted form of education in order to favour a unified conception of knowledge, Keats will always seem to go back to those first readings as a source of reference. They are indeed the foundations of this unique rapprochement between medicine and poetry which, in British Romanticism, is certainly specific to him. It takes a visionary painter and a close friend, John Hamilton Reynolds, to remind us, in his very axiomatic letter of 3 May 1818 that Keats will never cease to praise the medical world as a means to keep “every department of knowledge” alive. From this pattern of now two complementary backgrounds, he therefore extracts the binary substance of one “great whole”1: Were I to study physic or rather Medicine again, — I feel it would not make the least difference in my Poetry; when the Mind is in its infancy a Bias is in reality a Bias, but when we have acquired more strength, a Bias becomes no Bias.