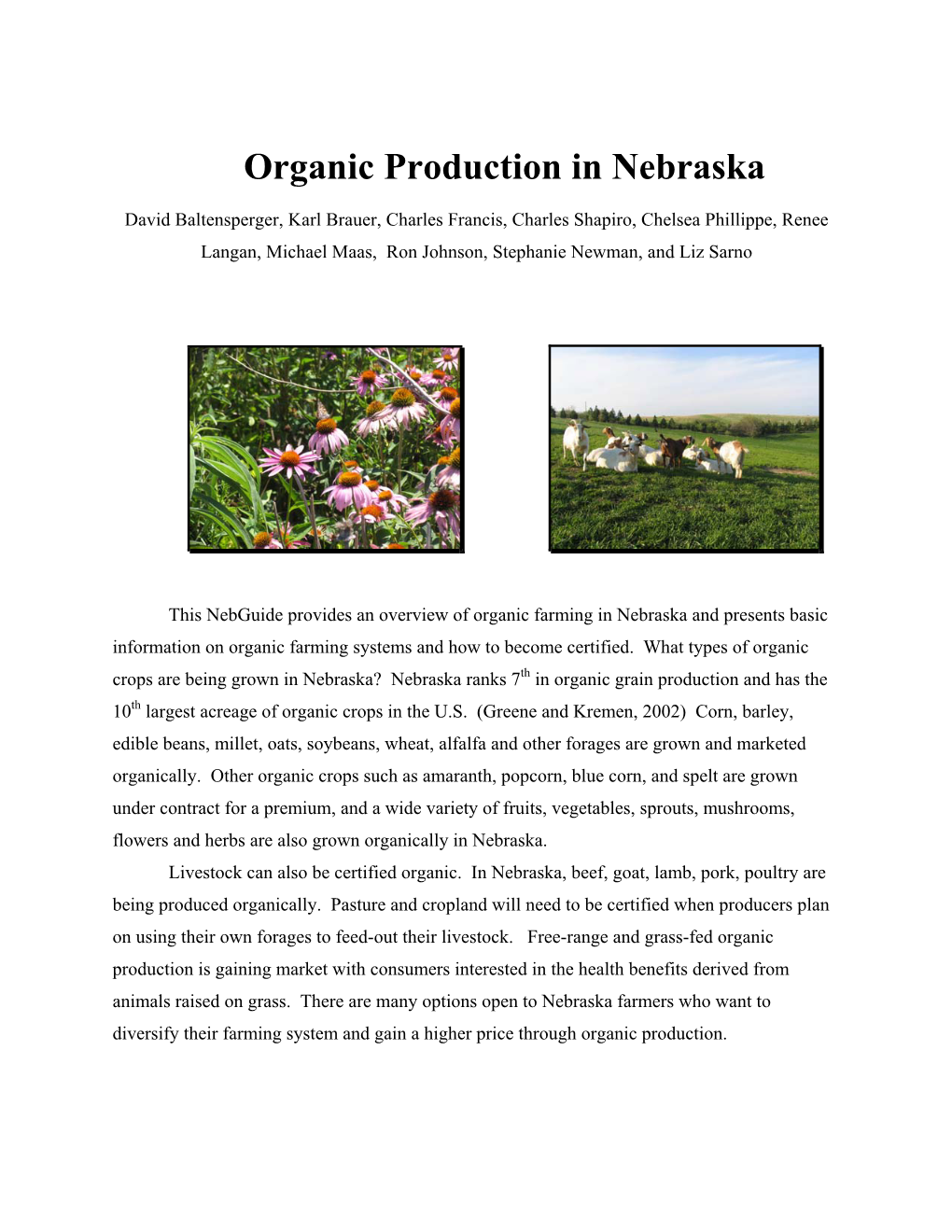

Organic Production in Nebraska

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dryland Farming in the Northwestern United States: a Nontechnical Overview

MISC0162E DRYLAND FARMING IN THE NORTHWESTERN UNITED STATES A Nontechnical Overview Proper citation: Granatstein, David. 1992. Dryland Farming in the Northwestern United States: A Nontechnical Overview. MISC0162, Washington State University Cooperative Extension, Pullman. 31 pp. About the Author and Project David Granatstein is Project Coordinator for the Northwest Dryland Cereal/Legume Cropping Systems Project, based in the Department of Crop and Soil Sciences, Wash- ington State University, Pullman, Washington. Work for this publication was conduct- ed there with cooperators from Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and Utah, under project numbers 3481 and 4481. This material is based on work supported by the Cooperative State Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, under Agreement No. 88-COOP-1-3525, with funding from the Western Region Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education Program. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publica- tion are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the view of the U.S. Depart- ment of Agriculture or Washington State University Extension. Permission to reprint Figure 1 granted by the American Society of Agronomy, Madison, WI. All photos except the cover were provided by David Granatstein. Cover photo: An artistic display of wheat sheaves at an agricultural exposition in the early 1900s. Photo courtesy of Historical Photograph Collections, WSU Libraries. Contents Introduction . 1 What Is Dryland Farming? . 2 What Is Sustainable Agriculture? . 3 History of Dryland Farming in the Northwestern States . 5 The Columbia River Country. 5 The Oregon Trail and Northern Plains. 8 Dryland Farming: Principles and Practices. 11 The Semiarid Environment in the Northwest. 11 Cropping Systems of the Region . -

Real Time Contingency Planning : Initial Experiences from AICRPDA

Real Time Contingency Planning: Initial Experiences from AICRPDA Ch Srinivasarao G Ravindra Chary PK Mishra R Nagarjuna Kumar GR Maruthi Sankar B Venkateswarlu AK Sikka 1985 National Initiative on Climate Resilient Agriculture All India Coordinated Research Project for Dryland Agriculture Central Research Institute for Dryland Agriculture Hyderabad - 500 059, India Citation: Srinivasarao Ch, Ravindra Chary G, Mishra PK, Nagarjuna Kumar R, Maruthi Sankar GR, Venkateswarlu B and Sikka AK. 2013. Real Time Contingency Planning: Initial Experiences from AICRPDA. All India Coordinated Research Project for Dryland Agriculture (AICRPDA),Central Research Institute for Dryland Agrciulture (CRIDA), ICAR, Hyderabad - 500 059, India. 63 p. 2013 Number of copies: 1000 Published by: Central Research Institute for Dryland Agriculture Santoshnagar, Hyderabad – 500059 Phone: +91 – 40 – 24530177, 24531063 Fax: +91 – 40 – 24531802 Website: http://www.crida.in or http:// crida.in Technical Assistance A Girija L Sriramulu Pradeepkumar Srivastava N Rani Manuscript Processing N. Lakshmi Narasu Front Cover Clockwise : (1) Sowing with Roto till dirll (S.K. Nagar, Gujarat); (2) Better Pigeonpea crop with mid season correction (Faizabad Dist. U.P.); (3) Saving horticulture plants through Pitcher system (Biswanath Chariali, Assam); (4) Supplemental irrigation from in farm pond through drip system to Sweet corn (Indore, M.P.) Back Cover Clockwise : (1) Agro advisory service though message on blackboard in NICRA village and SMS in mobile phones (Jamnagar Dist.Gujarat); (2) Mulching with groundnut shells in Cotton (Rajkot, Gujarat); (3) Compartment bunding for in situ moisture conservation in NICRA village (Solapur Dist. Maharashtra); (4) VCRMC Meeting in progress in NICRA village (Lakhimpur Dist. Assam); Printed at : Balaji Scan Pvt. -

SUSTAINABLE LAND MANAGEMENT and RESTORATION in the MIDDLE EAST and NORTH AFRICA REGION Issues, Challenges, and Recommendations

SUSTAINABLE LAND MANAGEMENT AND RESTORATION IN THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA REGION Issues, Challenges, and Recommendations Fall 2019 Environmnt, Nturl Rsourcs & Blu Econom 64270_SLM_CVR.indd 3 11/6/19 12:38 PM SUSTAINABLE LAND MANAGEMENT AND RESTORATION IN THE MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA REGION ISSUES, CHALLENGES, AND RECOMMENDATIONS 10116-SLM_64270.indd 1 11/19/19 1:37 PM © 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Direc- tors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denomina- tions, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: World Bank. 2019. Sustainable Land Management and Restoration in the Middle East and North Africa Region—Issues, Challenges, and Recommendations. Washington, DC. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to: World Bank Publications The World Bank Group 1818 H Street NW Washington, DC 20433 USA Fax: 202-522-2625 10116-SLM_64270.indd 2 11/19/19 1:37 PM TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments . -

Examples of Technologies to Combat Soil Erosion from WOCAT

Examples of technologies to combat soil erosion from WOCAT: The WOCAT Database. Some technologies are only available in the languages of the countries where they were collected. To access the technologies please visit WOCAT’s technology database at http://cdewocat.unibe.ch/wocatQT/qt_report.php. Please note you need to register. 1) Soil erosion by water Technology Country Name Description code AUS02 AUS No-till with controlled traffic This controlled traffic, no-till farming system (CT/NT) is practiced on a 1,900 ha farm on the broad... AUS03 AUS Green cane trash blanket Under conventional production systems, sugar cane is burnt before being harvested. This reduces the ... AUS03 AUS Green cane trash blanket Under conventional production systems, sugar cane is burnt before being harvested. This reduces the ... BAN01 BAN Hill Agroforestry On upper part of the slope natural forest tree species were allowed to grow and lower part with bamb... BAN02 BAN Multipurpose Earthen Dam The embankment is situated in the narrowest part of the valley using soil from nearby areas. Eart... BAN04 BAN Valley floor paddy terraced This technology is designed to maximize the land utilization cultivation through rice cultivation on terraced va... BEL1 BEL Non-inversion shallow cultivation The technology consists of agronomic measures. The most important thing is that the farmers are not ... BEL1 BEL Non-inversion shallow cultivation The technology consists of agronomic measures. The most important thing is that the farmers are not ... BEL1 BEL Non-inversion shallow cultivation The technology consists of agronomic measures. The most important thing is that the farmers are not .. -

Dryland Farming

Dryland farming Dryland farming and dry farming encompass specific agricultural techniques for the non-irrigated cultivation of crops. Dryland farming is associated with drylands, areas characterized by a cool wet season that is followed by a warm dry season. They are also associated with arid conditions or areas prone to drought or having scarce water resources. Additionally, arid-zone agriculture is being developed for this purpose. Contents Dryland farming Dryland farming in the Granada region in Spain Locations Crops Process Key elements of dryland farming Dry farming Locations Crops Process Arid-zone agriculture See also Areas Historical examples Research Techniques Other References Further reading External links Dryland farming Locations Dryland farming is used in the Great Plains, the Palouse plateau of Eastern Washington, and other arid regions of North America such as in the Southwestern United States and Mexico (see Agriculture in the Southwestern United States and Agriculture in the prehistoric Southwest), the Middle East and in other grain growing regions such as the steppes of Eurasia and Argentina. Dryland farming was introduced to southern Russia and Ukraine by Ukrainian Mennonites under the influence of Johann Cornies, making the region the breadbasket of Europe.[1 ] In Australia, it is widely practiced in all states but the Northern Territory. Crops Dryland farmed crops may include winter wheat, corn, beans, sunflowers or even watermelon. Successful dryland farming is possible with as little as 230 millimetres (9 in) of precipitation a year; higher rainfall increases the variety of crops. Native American tribes in the arid Southwest survived for hundreds of years on dryland farming in areas with less than 250 millimetres (10 in) of rain. -

Managing Our Soil Resource –Past, Present and Future

Managing Our Soil Resource –Past, Present and Future Farming Smarter Conference Lethbridge, AB Dec. 3, 2013 Ross H. McKenzie Retired Agronomy Research Scientist Outline • Alberta Soils – History • Soil Survey in Alberta • Notable Soil Science Research • Impacts of Agriculture, Industries, Urban and Rural Development on Alberta Landscapes • Comment on Future Agronomy Research Needs Alberta – 10,000 years ago! After that last glacial period – the Prairie landscape was transformed leaving behind varying types of parent material and topography. Types of Soil Parent Material Glacial Melt Water Ice Sheet Hummocky Outwash Moraine Ground Fluvial Moraine LS-SL Fluvial Lacustrine Lacustrine (Clay) (Loam-CL) Major Zonal Soil or Agro-Ecological Areas of Alberta Black Soils in Central Alberta Dark Gray & Gray Luvisolic Soils in North Central & Northern AB Dark Brown Soils in Southern Brown Soils in Central Alberta SE Alberta Solonetzic Soils – Azonal -high in sodium -poor structure -poorly suited for cultivation Over 75 years - soils across Alberta have been surveyed and soils classified Soil Survey in Alberta • Initiated in the early 1920’s with the Report #1 published in 1925 of the Ft MacLeod Sheet by Wyatt and Newton • The last report, #56 was published in 1996 of the Gleichen Sheet by Walker and Pettapiece • 8 Exploratory reports were also published AGRASID Background Existing soil information compiled over the last 75 years used various mapping concepts and classification systems and mapped at different scales AGRASID Agricultural Region of Alberta -

FOOD and SOIL RESOURCES Objectives 1. List Four

PART IV SUSTAINING NATURAL RESOURCES CHAPTER 14 - FOOD AND SOIL RESOURCES Objectives 1. List four major types of agriculture. Compare the energy sources, environmental impacts, yields, and sustainability of traditional and industrial agriculture. 2. Evaluate the green revolution. What were its successes? Its failures? Summarize the benefits and problems of livestock production over the history of agriculture. 3. Define interplanting, and explain its advantages. List and briefly describe four types of interplanting commonly used by traditional farmers. 4. Summarize the state of global food production. Define malnutrition, undernutrition, and overnutrition. Indicate how many people on Earth suffer from these problems and where these problems are most likely to occur. List six steps proposed by UNICEF to deal with malnutrition and undernutrition. Describe a strategy to reduce overnutrition. 5. Discuss the use of genetic engineering techniques to improve the human food supply. 6. Describe the problems of soil erosion and desertification. Describe both world and U.S. situations, and explain why most people are unaware of this problem. 7. Describe the problems of salinization and waterlogging of soils and how they can be controlled. 8. Define soil conservation. List nine ways to approach the problem of soil erosion. Be sure to distinguish between conventional-tillage and conservation-tillage farming. Describe a plan to maintain soil fertility. Be sure to distinguish between organic and inorganic fertilizers. 9. Summarize environmental impacts from agriculture. 10. Summarize food distribution problems. Describe the possibilities of increasing world food production by increasing crop yields, cultivating more land, and using unconventional foods and perennial crops. 11. Discuss problems associated with the production of livestock on rangeland. -

Water and Cereals in Drylands

Water and Cereals in Drylands P. Koohafkan Director, Land and Water Division, FAO, Rome B.A. Stewart Director, Dryland Agriculture Institute, West Texas A&M University, United States of America Published by The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and Earthscan publishing for a sustainable future London • Sterling, VA ii CONTENTS First published by The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and Earthscan in 2008 Copyright © FAO 2008 All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holder. Applications for such permission should be addressed to the Chief, Electronic Publishing Policy and Support Branch, Communication Division, FAO, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy or by email to [email protected]. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specifi c companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

Revised Sustainable Agriculture.Pdf

MODERN CONCEPTS OF AGRICULTURE Sustainable Agriculture A. Subba Rao Director Indian Institute of Soil Science Nabibagh, Berasia Road, Bhopal- 462 038 K.G. Mandal Indian Institute of Soil Science Nabibagh, Berasia Road, Bhopal- 462 038 (11-12- 2007) CONTENTS Definition Concepts Needs Indicators of Sustainability Ecological basis of Sustainability/Resource Management Profile of Indian Agriculture in relation to Sustainability Maintenance of Production base in Irrigated Agriculture Modernization of Agriculture and its relation with Sustainability Basic Ecological Principles of LEISA Some Promising LEISA Techniques and Practices Mulching Wind breaks Water Harvesting Strip Cropping Intercropping Trap and Decoy Crops Bio-intensive Gardening Contour Farming Integrated Crop-Livestock-Fish Farming Evaluation of Constraints Optimization of Farming Systems Keywords Carrying capacity, integrated farming 1 Agriculture is a key primary industry in India that makes a significant contribution to the wealth and quality of life for rural and urban communities in India. Definition Enshrined in the title of this chapter are two key words- ‘sustainable’ and ‘agriculture’. The word ‘sustain’, from the Latin sustinere (sus-, from below and tenere, to hold), to keep in existence or maintain, implies long-term support or permanence. The word ‘sustainability’ was used for the second time in 1712 by the German forester and mining scientist Hans Carl von Carlowitz in his book ‘Sylvicultura Oeconomica’. French and English scientists adopted the concept of planting trees and used the term ‘sustained yield forestry’ by Kara Taylor (ref., http://www.answers.com/topic/ sustainability). Sustainability is an attempt to provide the best outcomes for the human and natural environments both for the present and future. -

CRP 507 FARMING SYSTEMS (2 UNITS) Course Team

CRP 507 FARMING SYSTEMS (2 UNITS) Course Team: Dr Godwin Adu Alhassan (Course Writer) Department of Crop and Soil Sciences – NOUN Head of Department of Crop and Soil Sciences (Programme Leader) – NOUN Prof. Isaac S.R.Butswat ( Dean of Agricultural Sciences) – NOUN 1 NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA National Open University of Nigeria Plot 91, Cadastral Zone, University Village Nnamdi Azikiwe Expressway Jabi, Abuja Lagos Office 14/16 Ahmadu Bello Way Victoria Island Lagos e-mail: [email protected] URL: www.nou.edu.ng Published by: National Open University of Nigeria Printed 2018 ISBN: 978-058-542-7 All Rights Reserved 2 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………. What you will Learn in this Course …………………………. Course Aims …………………………………………………… Course Objectives ……………………………………………… Working through this Course …………………………………... Course Materials ……………………………………………….. Study Units ……………………………………………………… Sets of References and other Resources Assessment ……………………………………………………… Tutor-Marked Assignment ……………………………………… Final Examination and Grading ………………………………… Course Marking Scheme ………………………………………... Facilitators/Tutors and Tutorials ………………………………… Summary ………………………………………………………… 3 INTRODUCTION Farming Systems (CRP 507) is one semester course of two credit hours maximum. It will be available to all students offering crop production in their final year of B. Agriculture degree. The course will consist of five units, which involves good knowledge in the natural sciences and rural sociology. What constitutes the farming system of a community or place is dependent upon the culture, soil, vegetation, climate, water availability, income, available markets and diets of the people. The decision to produce a particular crop or rare a particular livestock is the product of the man’s environment. This includes the physical, biological, socio-economic environment of the farmers. Sometimes government or some funding intervention may alter or change the farmers’ decision to produce. -

Agronomic Measures

Vegetative Measures For Watershed Development Session - 3 AGRONOMIC MEASURES People’s Science Institute Agronomic Measures Content • What are the different agro-climatic zones of Meghalaya? • What are the major farming systems of Meghalaya? • What are the major farm based enterprises? • What are the major constraints in farming in Meghalaya? • What is sustainable farming? • What are the different types of agronomic measures? • What are the benefits of these measures ? Agronomic Measures Agro-Climatic Zones of Meghalaya Zones Location Soil Type Principal Crops 1 Warm and humid with medium Hills and northern slopes in north and Light to medium Rice, maize, wheat, rainfall (1270-2032 mm) western parts of West Garo Hills, texture with generally jute and mesta, northern parts of East and West Khasi high depth. rapeseed-mustard, Hills and north eastern parts of Jaintia cotton and ginger Hills. 2 Humid and moderately cold in Central plateau of Garo Hills and a Light to medium in Maize, ginger, cotton winter with high rainfall (2800- portion of the Central plateau of West texture and generally and tea 4000 mm): Khasi Hills. very deep 3 Humid with moderately warm Central plateau of East Khasi Hills, West Light to medium in Vegetables, especially summer and severe cold winter with Khasi Hills and Jaintia Hills texture and generally potato, upland rice, tea high rainfall (2800-6000 mm) very deep. and ginger 4 Humid and warm with very high Southern slope comprising of eastern Light to medium in Oranges, turmeric and rainfall (4000-10000 mm) part of Jaintia Hills, southern part of East texture and deep to soybean Khasi Hills and a portion of southern very deep. -

Strip Cropping .Soil Conservation

Strip Cropping .Soil Conservation •"feJII;,:, FAttMERS' BULLETIN No. 1776 us. DEPAKTMKNT OF AGRICULTURE STRIP CROPPING FOR SOIL CONSERVATION By WALTER V. KEIX, senior agronomist, Section of Agronomy and Range Man agement, and GROVER F. BROWN, regional agronomist. Region 1, Division of Conservation Operations, Soil Conservation Service CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 Correction strip 19 Three types of strip cropping 4 Grassed waterways 20 Conservation measures -.. 6 Buffer or spreader strips 21 Mechanical structures 6 Turn strips 23 Vegetative controls 7 Border strips 24 Contourstrip cropping..- - -- 8 Method of laying out strips 26 Advantages of strip cropping 9 Laying out strips on terraced land. ..- 27 Some economies of strip cropping 12 Laying out strips on land to be terraced 30 Reduction of soil loss 12 Field strip cropping 31 Increase in yields and farm income 12 Wind strip cropping - 31 Savings for h ighway departments 13 Crops permitting erosion 33 Reduction in fertilizer costs IS Cover crops 33 Economies in farm power - 14 Combining protective and soil-buUdlng crops. 33 Physical soil factors affecting erosion 14 Rotations -- 35 Width of strips 16 Perennial strips in the Southeast.. 36 Deviation from the contour 18 INTRODUCTION O FARM SUCCESSFULLY and continuously on steep hill sides has always been a major problem to the farmer. The dif Tficulty of holding the land has been easily recognized because on these steep slopes erosion progresses at a rapid rate and is visible from year to year. While the same destructive movement of soils has been taking place on the more gentle slopes, it is not as spec tacular and usually has been overlooked until most of the produc tive topsoil was gone from the fields and the plows began turning up the infertile subsoil.