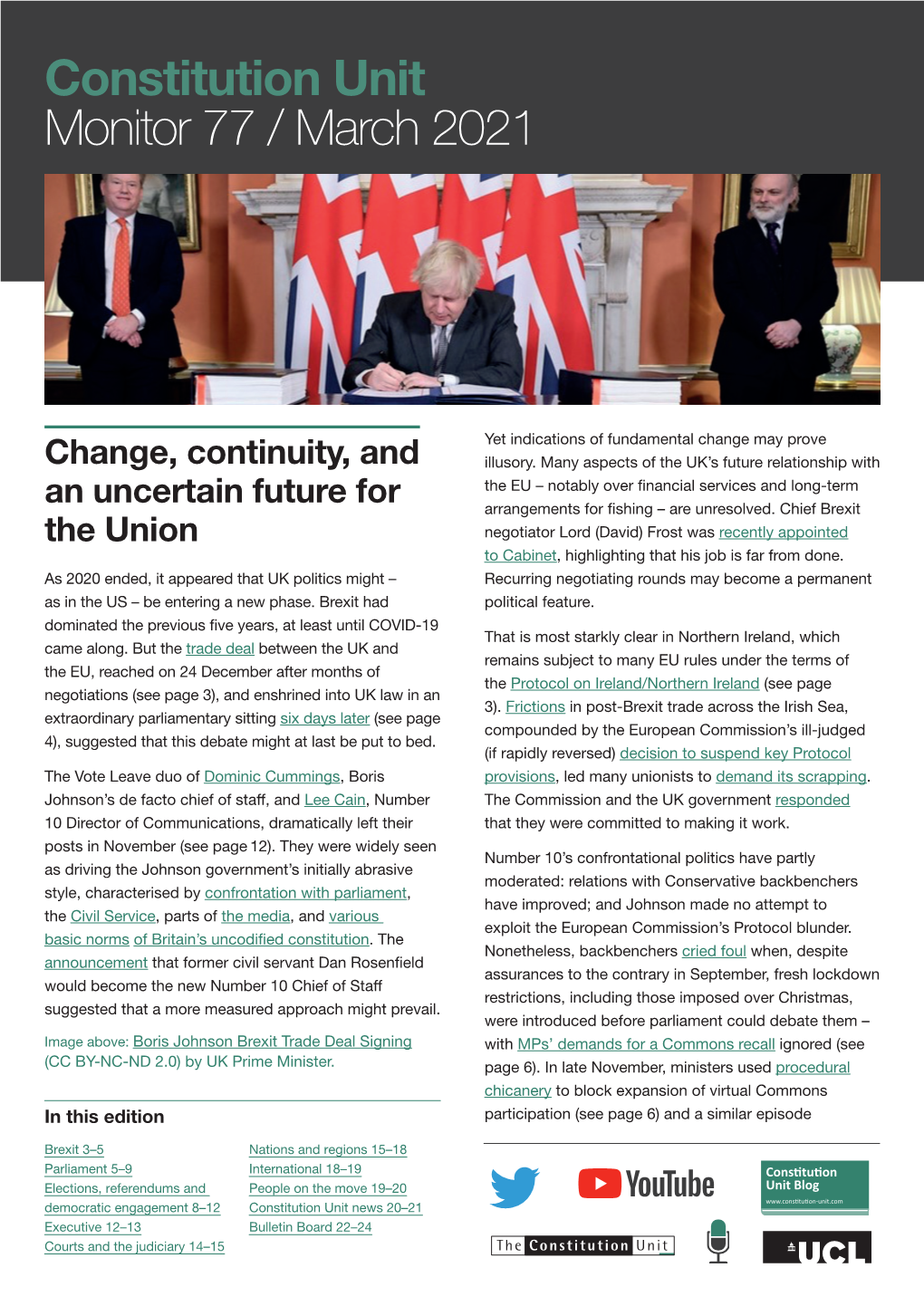

Constitution Unit Monitor 77 / March 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft Letter to the Prime Minister

HOUSE OF COMMONS LONDO sw 1A OAA Rt. Hon. David Cameron MP Prime Minister 10 Downing Street London SW1A2AA Dear Prime Minister, As Members of Parliament for Staffordshire, we write to express our deep concern at the withdrawal of 3rd Battalion, the Mercian Regiment (The Staffards) from the Order of Battle. The Battalion has a proud history which can be traced back to its first raising at the King's Head Inn, Lichfield, in 1705. It served in Martinique, South Africa, Flanders, Gallipoli, Anzio and Arnhem. More recently, photographs of 3 Mercian fighting in Basra, became defining images of the Iraq campaign. We all recognise the difficult financial climate and the constraints that imposes on the Ministry of Defence. We understand that savings must be made. However, we also know that the decision to withdraw 3 Mercian will be distressing for all those currently serving, particularly those that might face redundancy, for their families and for those former Staffards who proudly recall their service. We know that it is the responsibility of the Mercian Regiment, as reorganised, to decide how best to reflect its history and antecedents. But as there is no longer any senior former Stafford serving on its staff, we hope that you will do all you can to encourage the Regiment to preserve and cherish the symbols, traditions and heritage of 3 Mercian within its ranks. 2 Mercian is known now as the Worcester and Sherwood Foresters as a result of previous amalgamations and we hope that a similar formula can be found to remember the Staffords. -

IICSA Inquiry-Westminster 29 March 2019

IICSA Inquiry-Westminster 29 March 2019 1 Friday, 29 March 2019 1 various matters that arose during Ms Reason's evidence. 2 (10.00 am) 2 That is GNP001006. 3 THE CHAIR: Good morning, everyone, and welcome to the final 3 We invite you to adduce the witness statement of 4 day of this public hearing. Ms Beattie? 4 Christopher Horne, dated March 2019. Mr Horne describes 5 Witness statements adduced by MS BEATTIE 5 how, during the 1972 by-election, there was talk that 6 MS BEATTIE: Good morning, chair. Before we turn to closing 6 Cyril Smith had committed sexual offences with young 7 submissions, there is some further evidence that we 7 boys. Mr Horne, who was a supporter of the Conservative 8 would invite you to adduce. The first is the second 8 Party candidate, David Trippier, says the local police 9 witness statement of Gary Richardson, a detective 9 took action to ensure that this information was not 10 superintendent British Transport Police, dated 10 disseminated, including by a police visit to the 11 13 March 2019. This concerns email correspondence 11 Conservative Party campaign office where the police said 12 received by the British Transport Police from 12 that any mention of Cyril Smith's predilection for young 13 North Wales Police in 2017 about Peter Morrison being 13 boys would be treated as a criminal offence and lead to 14 taken off a train at Crewe Railway Station. The British 14 an order to stay out of the by-election. That reference 15 Transport Police did not take any further action in 15 is INQ004206. -

1 ANDREW MARR SHOW, 9TH MAY, 2021 – JOHN Mcdonnell and ANAS SARWAR

1 ANDREW MARR SHOW, 9TH MAY, 2021 – JOHN McDONNELL AND ANAS SARWAR ANDREW MARR SHOW, 9TH MAY, 2021 JOHN McDONNELL, Former Shadow Chancellor And ANAS SARWAR, Leader, Scottish Labour Party (Please check against delivery (uncorrected copies)) AM: Keir Starmer says he takes full responsibility for Labour’s poor performance in the elections in England. But last night, to the fury of many in the party he appears to have sacked Angela Rayner as Party Chair and Election Coordinator. He can’t sack her from her elected position as Deputy Leader of the Labour Party, but overnight there have been signs that things are coming apart. Andy Burnham, the Mayor Manchester, tweeted about Angela Rayner, ‘I can’t support this.’ Trouble ahead. I’m going to speak now to John McDonnell, Jeremy Corbyn’s former Shadow Chancellor and to Anas Sarwar, the Labour Party Leader here in Scotland. He lost two seats yesterday but he says the party are now on the right path. John McDonnell, first of all, I don’t know if you’ve had a chance to talk to Angela Rayner. Do you know whether she has been sacked or not? There seems to be some confusion this morning. JM: No, I haven’t spoken to Angie. Let’s be clear, I have no brief for Angie, I didn’t support her as Deputy Leader. I supported Richard Burgon, but when the Leader of the Party on Friday says he takes full responsibility for the election result in Hartlepool in particular, and then scapegoats Angie Rayner, I think many of us feel that was unfair, particularly as we all know actually Keir style of Leadership is that his office controls everything. -

Register of Interests of Members’ Secretaries and Research Assistants

REGISTER OF INTERESTS OF MEMBERS’ SECRETARIES AND RESEARCH ASSISTANTS (As at 11 July 2018) INTRODUCTION Purpose and Form of the Register In accordance with Resolutions made by the House of Commons on 17 December 1985 and 28 June 1993, holders of photo-identity passes as Members’ secretaries or research assistants are in essence required to register: ‘Any occupation or employment for which you receive over £380 from the same source in the course of a calendar year, if that occupation or employment is in any way advantaged by the privileged access to Parliament afforded by your pass. Any gift (eg jewellery) or benefit (eg hospitality, services) that you receive, if the gift or benefit in any way relates to or arises from your work in Parliament and its value exceeds £380 in the course of a calendar year.’ In Section 1 of the Register entries are listed alphabetically according to the staff member’s surname. Section 2 contains exactly the same information but entries are instead listed according to the sponsoring Member’s name. Administration and Inspection of the Register The Register is compiled and maintained by the Office of the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards. Anyone whose details are entered on the Register is required to notify that office of any change in their registrable interests within 28 days of such a change arising. An updated edition of the Register is published approximately every 6 weeks when the House is sitting. Changes to the rules governing the Register are determined by the Committee on Standards in the House of Commons, although where such changes are substantial they are put by the Committee to the House for approval before being implemented. -

The Performance of the Department for Culture Media and Sport 2012-13

DEPARTMENTAL OVERVIEW The performance of the Department for Culture, Media & Sport 2012-13 MARCH 2014 Our vision is to help the nation spend wisely. Our public audit perspective helps Parliament hold government to account and improve public services. The National Audit Office scrutinises public spending for Parliament and is independent of government. The Comptroller and Auditor General (C&AG), Amyas Morse, is an Officer of the House of Commons and leads the NAO, which employs some 860 staff. The C&AG certifies the accounts of all government departments and many other public sector bodies. He has statutory authority to examine and report to Parliament on whether departments and the bodies they fund have used their resources efficiently, effectively, and with economy. Our studies evaluate the value for money of public spending, nationally and locally. Our recommendations and reports on good practice help government improve public services, and our work led to audited savings of almost £1.2 billion in 2012. Contents Introduction Aim and scope of this briefing 4 Part One About the Department 5 Part Two Recent NAO work on the Department 21 Appendix One The Department’s sponsored bodies at 1 April 2013 30 Appendix Two Results of the Civil Service People Survey 2013 32 Appendix Three Publications by the NAO on the Department since April 2012 34 Appendix Four Cross-government reports of relevance to the Department in 2013 35 Links to external websites were valid at the time of publication of this report. The National Audit Office is not responsible for the future validity of the links. -

Appointment of the Chair of the Social Mobility Commission

House of Commons Education Committee Appointment of the Chair of the Social Mobility Commission Fourth Report of Session 2017–19 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 11 July 2018 HC 1048 Published on 13 July 2018 by authority of the House of Commons The Education Committee The Education Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Department for Education and its associated public bodies. Current membership Rt Hon Robert Halfon MP (Conservative, Harlow) (Chair) Lucy Allan MP (Conservative, Telford) Michelle Donelan MP (Conservative, Chippenham) Marion Fellows MP (Scottish National Party, Motherwell and Wishaw) James Frith MP (Labour, Bury North) Emma Hardy MP (Labour, Kingston upon Hull West and Hessle) Trudy Harrison MP (Conservative, Copeland) Ian Mearns MP (Labour, Gateshead) Lucy Powell MP (Labour (Co-op), Manchester Central) Thelma Walker MP (Labour, Colne Valley) Mr William Wragg MP (Conservative, Hazel Grove) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications Committee reports are published on the Committee’s website at www.parliament.uk/education-committee and in print by Order of the House. Evidence relating to this report is published on the inquiry publications page of the Committee’s website. Committee staff The current staff of the Committee are Richard Ward (Clerk), Katya Cassidy (Second Clerk), Anna Connell-Smith (Committee Specialist), Chloë Cockett (Committee Specialist), Tommer Spence (Inquiry Manager), Jonathan Arkless (Senior Committee Assistant), Hajera Begum (Committee Apprentice), Gary Calder (Senior Media Officer) and Oliver Florence (Media Officer). -

Z675928x Margaret Hodge Mp 06/10/2011 Z9080283 Lorely

Z675928X MARGARET HODGE MP 06/10/2011 Z9080283 LORELY BURT MP 08/10/2011 Z5702798 PAUL FARRELLY MP 09/10/2011 Z5651644 NORMAN LAMB 09/10/2011 Z236177X ROBERT HALFON MP 11/10/2011 Z2326282 MARCUS JONES MP 11/10/2011 Z2409343 CHARLOTTE LESLIE 12/10/2011 Z2415104 CATHERINE MCKINNELL 14/10/2011 Z2416602 STEPHEN MOSLEY 18/10/2011 Z5957328 JOAN RUDDOCK MP 18/10/2011 Z2375838 ROBIN WALKER MP 19/10/2011 Z1907445 ANNE MCINTOSH MP 20/10/2011 Z2408027 IAN LAVERY MP 21/10/2011 Z1951398 ROGER WILLIAMS 21/10/2011 Z7209413 ALISTAIR CARMICHAEL 24/10/2011 Z2423448 NIGEL MILLS MP 24/10/2011 Z2423360 BEN GUMMER MP 25/10/2011 Z2423633 MIKE WEATHERLEY MP 25/10/2011 Z5092044 GERAINT DAVIES MP 26/10/2011 Z2425526 KARL TURNER MP 27/10/2011 Z242877X DAVID MORRIS MP 28/10/2011 Z2414680 JAMES MORRIS MP 28/10/2011 Z2428399 PHILLIP LEE MP 31/10/2011 Z2429528 IAN MEARNS MP 31/10/2011 Z2329673 DR EILIDH WHITEFORD MP 31/10/2011 Z9252691 MADELEINE MOON MP 01/11/2011 Z2431014 GAVIN WILLIAMSON MP 01/11/2011 Z2414601 DAVID MOWAT MP 02/11/2011 Z2384782 CHRISTOPHER LESLIE MP 04/11/2011 Z7322798 ANDREW SLAUGHTER 05/11/2011 Z9265248 IAN AUSTIN MP 08/11/2011 Z2424608 AMBER RUDD MP 09/11/2011 Z241465X SIMON KIRBY MP 10/11/2011 Z2422243 PAUL MAYNARD MP 10/11/2011 Z2261940 TESSA MUNT MP 10/11/2011 Z5928278 VERNON RODNEY COAKER MP 11/11/2011 Z5402015 STEPHEN TIMMS MP 11/11/2011 Z1889879 BRIAN BINLEY MP 12/11/2011 Z5564713 ANDY BURNHAM MP 12/11/2011 Z4665783 EDWARD GARNIER QC MP 12/11/2011 Z907501X DANIEL KAWCZYNSKI MP 12/11/2011 Z728149X JOHN ROBERTSON MP 12/11/2011 Z5611939 CHRIS -

Qatar, Turkey Sign Pacts to Cement Ties Zamir, Erdogan Attend Sixth Meeting of the Qatar-Turkey Supreme Strategic Committee

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 New investment Qatar 2022 World avenues opening Cup will transform up in Qatar on Covid attitude towards handling success, says sustainability: QFCA chief al-Jaida al-Thawadi published in QATAR since 1978 FRIDAY Vol. XXXXI No. 11745 November 27, 2020 Rabia II 12, 1442 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan inspect a guard of honour in Ankara yesterday. His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani holds talks with Erdogan. Qatar, Turkey sign pacts to cement ties zAmir, Erdogan attend sixth meeting of the Qatar-Turkey Supreme Strategic Committee QNA presidential palace in Ankara. Authority and Altin Halic on potential Ministry of Trade, a memorandum companying the Amir and Turkey’s national Airport by Turkish Minister Ankara The meeting also reviewed the out- joint investment in the Golden Horn of understanding on co-operation in ministers and ranking offi cials. of Finance and Treasury Lotfi Alwan, comes of previous sessions, and ways project, a deal to purchase a stake in managing water, a letter of intent be- The Amir was given an offi cial reception spokesperson for the Turkish Presi- to enhance the committee’s work to ad- Borsa Istanbul, an agreement selling tween the Qatari Ministry of Finance upon arrival at the presidential palace. dency Ibrahim Kalin, Qatar’s ambassa- is Highness the Amir Sheikh vance the interest of the two countries. and purchasing Ortadogu Antalya port and the Turkish Ministry of Finance Later the Amir attended a luncheon dor to Turkey Salem Mubarak Shafi al- Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani The sides also discussed the latest between Global Liman and QTerminals, and Treasury, a memorandum of un- banquet held by Erdogan. -

The Rt Hon Priti Patel MP Home Secretary Home Office 2 Marsham Street London SW1P 4DF

The Rt Hon Priti Patel MP Home Secretary Home Office 2 Marsham Street London SW1P 4DF 18 July 2020 Dear Home Secretary Protecting people being exploited in UK garment factories We are writing as a broad coalition of parliamentarians, businesses, investors and civil society organisations about our concerns regarding the unethical labour practices taking place in garment factories across the UK. We request that urgent action is taken by the Government to implement a ‘Fit to Trade’ licensing scheme that ensures all garment factories are meeting their legal obligations to their employees. As we have seen in the media over the last month, a concerning number of garment workers in key hubs in the UK, such as Leicester, have continued to work in factories throughout lockdown without adequate PPE or social distancing measures in place. These reports on the terrible working conditions people face in UK garment factories add weight to concerns which have been raised over the last five years by academics and Parliamentary Committees about the gross underpayment of the national living wage and serious breaches of health and safety law in these workplaces. Unless action is taken now, thousands more people will likely face exploitation. Responsible retailers and brands have made significant efforts to improve labour practices in garment factories, but whilst this has supported improvements in a handful of factories, it has not led to the desired system-wide changes needed. Most leading fashion retailers have therefore significantly scaled down their UK supply. There is now an opportunity for the UK to become a world-leading, innovative, export led, ethical fashion and textile manufacturing industry, delivering better skilled jobs, that in times of crisis can also be utilised for PPE production. -

Full List of Her Majesty's Government Correct As of 30 June 2017

Full list of Her Majesty’s Government Correct as of 30 June 2017 Cabinet Also attend Cabinet Foreign and Commonwealth Office Department for Education Department for Communities Department for Work PRIME MINISTER, FIRST LORD OF THE TREASURY CHIEF SECRETARY TO THE TREASURY SECRETARY OF STATE FOR FOREIGN AND COMMONWEALTH AFFAIRS SECRETARY OF STATE FOR EDUCATION AND and Local Government and Pensions AND MINISTER FOR THE CIVIL SERVICE MINISTER FOR WOMEN AND EQUALITIES Rt Hon Elizabeth Truss MP Rt Hon Boris Johnson MP SECRETARY OF STATE FOR COMMUNITIES AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT SECRETARY OF STATE FOR WORK AND PENSIONS Rt Hon Theresa May MP Rt Hon Justine Greening MP LORD PRESIDENT OF THE COUNCIL AND MINISTER OF STATE FOR EUROPE AND THE AMERICAS (MINISTERIAL CHAMPION FOR THE MIDLANDS ENGINE) Rt Hon David Gauke MP FIRST SECRETARY OF STATE AND MINISTER FOR THE CABINET OFFICE LEADER OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS MINISTER OF STATE FOR SCHOOL STANDARDS Rt Hon Sajid Javid MP Rt Hon Sir Alan Duncan KCMG MP MINISTER OF STATE FOR EMPLOYMENT Rt Hon Damian Green MP Rt Hon Andrea Leadsom MP Rt Hon Nick Gibb MP MINISTER OF STATE FOR AFRICA MINISTER OF STATE Damian Hinds MP CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER CHIEF WHIP (PARLIAMENTARY SECRETARY TO THE TREASURY) MINISTER OF STATE Alok Sharma MP Rory Stewart OBE MP (jointly with Department for MINISTER OF STATE FOR DISABLED PEOPLE, HEALTH AND WORK Rt Hon Philip Hammond MP Rt Hon Gavin Williamson CBE MP International Development) Rt Hon Anne Milton MP PARLIAMENTARY UNDER SECRETARY OF STATE Penny Mordaunt MP SECRETARY OF STATE -

The Conservative Agenda for Constitutional Reform

UCL DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE The Constitution Unit Department of Political Science UniversityThe Constitution College London Unit 29–30 Tavistock Square London WC1H 9QU phone: 020 7679 4977 fax: 020 7679 4978 The Conservative email: [email protected] www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit A genda for Constitutional The Constitution Unit at UCL is the UK’s foremost independent research body on constitutional change. It is part of the UCL School of Public Policy. THE CONSERVATIVE Robert Hazell founded the Constitution Unit in 1995 to do detailed research and planning on constitutional reform in the UK. The Unit has done work on every aspect AGENDA of the UK’s constitutional reform programme: devolution in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and the English regions, reform of the House of Lords, electoral reform, R parliamentary reform, the new Supreme Court, the conduct of referendums, freedom eform Prof FOR CONSTITUTIONAL of information, the Human Rights Act. The Unit is the only body in the UK to cover the whole of the constitutional reform agenda. REFORM The Unit conducts academic research on current or future policy issues, often in collaboration with other universities and partners from overseas. We organise regular R programmes of seminars and conferences. We do consultancy work for government obert and other public bodies. We act as special advisers to government departments and H parliamentary committees. We work closely with government, parliament and the azell judiciary. All our work has a sharply practical focus, is concise and clearly written, timely and relevant to policy makers and practitioners. The Unit has always been multi disciplinary, with academic researchers drawn mainly from politics and law. -

Download (9MB)

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details 2018 Behavioural Models for Identifying Authenticity in the Twitter Feeds of UK Members of Parliament A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF UK MPS’ TWEETS BETWEEN 2011 AND 2012; A LONGITUDINAL STUDY MARK MARGARETTEN Mark Stuart Margaretten Submitted for the degree of Doctor of PhilosoPhy at the University of Sussex June 2018 1 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................ 1 DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 FIGURES ........................................................................................................................................... 6 TABLES ............................................................................................................................................