Digital Integration/Invasion in Jatra: a Critical Investigation in Bengal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL Millenniumpost.In

ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL millenniumpost.in pages millenniumpost NO HALF TRUTHS th28 NEW DELHI & KOLKATA | MAY 2018 Contents “Dharma and Dhamma have come home to the sacred soil of 63 Simplifying Doing Trade this ancient land of faith, wisdom and enlightenment” Narendra Modi's Compelling Narrative 5 Honourable President Ram Nath Kovind gave this inaugural address at the International Conference on Delineating Development: 6 The Bengal Model State and Social Order in Dharma-Dhamma Traditions, on January 11, 2018, at Nalanda University, highlighting India’s historical commitment to ethical development, intellectual enrichment & self-reformation 8 Media: Varying Contours How Central Banks Fail am happy to be here for 10 the inauguration of the International Conference Unmistakable Areas of on State and Social Order 12 Hope & Despair in IDharma-Dhamma Traditions being organised by the Nalanda University in partnership with the Vietnam The Universal Religion Buddhist University, India Foundation, 14 of Swami Vivekananda and the Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. In particular, Ethical Healthcare: A I must welcome the international scholars and delegates, from 11 16 Collective Responsibility countries, who have arrived here for this conference. Idea of India I understand this is the fourth 17 International Dharma-Dhamma Conference but the first to be hosted An Indian Summer by Nalanda University and in the state 18 for Indian Art of Bihar. In a sense, the twin traditions of Dharma and Dhamma have come home. They have come home to the PMUY: Enlightening sacred soil of this ancient land of faith, 21 Rural Lives wisdom and enlightenment – this land of Lord Buddha. -

Program and Abstracts

Indian Council for Cultural Relations. Consulate General of India in St.Petersburg Russian Academy of Sciences, St.Petersburg scientific center, United Council for Humanities and Social Sciences. Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera) RAS. Institute of Oriental Manuscripts RAS. Oriental faculty, St.Petersburg State University. St.Petersburg Association for International cooperation GERASIM LEBEDEV (1749-1817) AND THE DAWN OF INDIAN NATIONAL RENAISSANCE Program and Abstracts Saint-Petersburg, October 25-27, 2018 Индийский совет по культурным связям. Генеральное консульство Индии в Санкт-Петербурге. Российская академия наук, Санкт-Петербургский научный центр, Объединенный научный совет по общественным и гуманитарным наукам. Музей антропологии и этнографии (Кунсткамера) РАН. Институт восточных рукописей РАН Восточный факультет СПбГУ. Санкт-Петербургская ассоциация международного сотрудничества ГЕРАСИМ ЛЕБЕДЕВ (1749-1817) И ЗАРЯ ИНДИЙСКОГО НАЦИОНАЛЬНОГО ВОЗРОЖДЕНИЯ Программа и тезисы Санкт-Петербург, 25-27 октября 2018 г. PROGRAM THURSDAY, OCTOBER 25 St.Peterburg Scientific Centre of the Russian Academy of Sciences, University Embankment 5. 10:30 – 10.55 Participants Registration 11:00 Inaugural Addresses Consul General of India at St. Petersburg Mr. DEEPAK MIGLANI Member of the RAS, Chairman of the United Council for Humanities and Social Sciences NIKOLAI N. KAZANSKY Director of the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, Associate Member of the RAS ANDREI V. GOLOVNEV Director of the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts, Professor IRINA F. POPOVA Chairman of the Board, St. Petersburg Association for International Cooperation, MARGARITA F. MUDRAK Head of the Indian Philology Chair, Oriental Faculty, SPb State University, Associate Professor SVETLANA O. TSVETKOVA THURSDAY SESSION. Chaiperson: S.O. Tsvetkova 1. SUDIPTO CHATTERJEE (Kolkata). -

Folk and Traditional Media: a Powerful Tool for Rural Development

© Kamla-Raj 2011 J Communication, 2(1): 41-47 (2011) Folk and Traditional Media: A Powerful Tool for Rural Development Manashi Mohanty and Pritishri Parhi* College of Home Science, O.U.A.T, Bhubaneswar 751 003, Orissa, India Telephone: *<9437302802>, *<9437231705>; E-mail: [email protected] KEYWORDS Folk Media. Traditional Media. Rural Development ABSTRACT Tradition is the cumulative heritage of society which permeates through all levels of social organization, social structure and the structure of personality. The tradition which is the cumulative social heritage in the form of habit, custom, attitude and the way of life is transmitted from generation to generation either through written words or words of mouth. It was planned to focus the study on stakeholders of rural development and folk media persons, so that their experience, difficulties, suggestion etc. could be collected to make the study realistic and feasible. The study was conducted in the state of Orissa comprising 30 districts out of which 3 coastal districts, namely, Cuttack, Puri and Balasore were selected according to the specific folk media culture namely, ‘Jatra’, ‘Pattachitra’ , ‘Pala’, ‘Daskathjia’ for their cultural aspects and uses. The study reveals that majority of the respondents felt that folk media is used quite significantly in rural development for its cultural aspect but in the era of Information and Communication Technology (ICT), it is losing its significance. The study supports the idea that folk media can be used effectively along with the electronic media for the sake of the development of rural society INTRODUCTION their willing participation in the development of a country is well recognized form of reaching The complex social system with different people, communicating with them and equipp- castes, classes, creeds and tribes in our country ing them with new skills. -

The Actresses of the Public Theatre in Calcutta in the 19Th & 20Th Century

Revista Digital do e-ISSN 1984-4301 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras da PUCRS http://revistaseletronicas.pucrs.br/ojs/index.php/letronica/ Porto Alegre, v. 11, n. esp. (supl. 1), s113-s124, setembro 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.15448/1984-4301.2018.s.30663 Memory and the written testimony: the actresses of the public theatre in Calcutta in the 19th & 20th century Memória e testemunho escrito: as atrizes do teatro público em Calcutá nos séculos XIX e XX Sarvani Gooptu1 Netaji Institute for Asian Studies, NIAS, in Kolkata, India. 1 Professor in Asian Literary and Cultural Studies ABSTRACT: Modern theatrical performances in Bengali language in Calcutta, the capital of British colonial rule, thrived from the mid-nineteenth at the Netaji Institute for Asian Studies, NIAS, in Kolkata, India. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1564-1225 E-mail: [email protected] century though they did not include women performers till 1874. The story of the early actresses is difficult to trace due to a lack of evidence in primarycontemporary material sources. and the So scatteredthough a researcher references is to vaguely these legendary aware of their actresses significance in vernacular and contribution journals and to Indian memoirs, theatre, to recreate they have the remained stories of shadowy some of figures – nameless except for those few who have left a written testimony of their lives and activities. It is my intention through the study of this Keywords: Actresses; Bengali Theatre; Social pariahs; Performance and creative output; Memory and written testimony. these divas and draw a connection between testimony and lasting memory. -

Between Violence and Democracy: Bengali Theatre 1965–75

BETWEEN VIOLENCE AND DEMOCRACY / Sudeshna Banerjee / 1 BETWEEN VIOLENCE AND DEMOCRACY: BENGALI THEATRE 1965–75 SUDESHNA BANERJEE 1 The roots of representation of violence in Bengali theatre can be traced back to the tortuous strands of socio-political events that took place during the 1940s, virtually the last phase of British rule in India. While negotiations between the British, the Congress and the Muslim League were pushing the country towards a painful freedom, accompanied by widespread communal violence and an equally tragic Partition, with Bengal and Punjab bearing, perhaps, the worst brunt of it all; the INA release movement, the RIN Mutiny in 1945-46, numerous strikes, and armed peasant uprisings—Tebhaga in Bengal, Punnapra-Vayalar in Travancore and Telengana revolt in Hyderabad—had underscored the potency of popular movements. The Left-oriented, educated middle class including a large body of students, poets, writers, painters, playwrights and actors in Bengal became actively involved in popular movements, upholding the cause of and fighting for the marginalized and the downtrodden. The strong Left consciousness, though hardly reflected in electoral politics, emerged as a weapon to counter State violence and repression unleashed against the Left. A glance at a chronology of events from October 1947 to 1950 reflects a series of violent repressive measures including indiscriminate firing (even within the prisons) that Left movements faced all over the state. The history of post–1964 West Bengal is ridden by contradictions in the manifestation of the Left in representative politics. The complications and contradictions that came to dominate politics in West Bengal through the 1960s and ’70s came to a restive lull with the Left Front coming to power in 1977. -

Hindi Theater Is Not Seen in Any Other Theatre

NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN DISCUSSION ON HINDI THEATRE FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN AUDIO LIBRARY THE PRESENT SCENARIO OF HINDI THEATRE IN CALCUTTA ON th 15 May 1983 AT NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN PARTICIPANTS PRATIBHA AGRAWAL, SAMIK BANDYOPADHYAY, SHIV KUMAR JOSHI, SHYAMANAND JALAN, MANAMOHON THAKORE SHEO KUMAR JHUNJHUNWALA, SWRAN CHOWDHURY, TAPAS SEN, BIMAL LATH, GAYANWATI LATH, SURESH DUTT, PRAMOD SHROFF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN EE 8, SECTOR 2, SALT LAKE, KOLKATA 91 MAIL : [email protected] Phone (033)23217667 1 NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN Pratibha Agrawal We are recording the discussion on “The present scenario of the Hindi Theatre in Calcutta”. The participants include – Kishen Kumar, Shymanand Jalan, Shiv Kumar Joshi, Shiv Kumar Jhunjhunwala, Manamohan Thakore1, Samik Banerjee, Dharani Ghosh, Usha Ganguly2 and Bimal Lath. We welcome all of you on behalf of Natya Shodh Sansthan. For quite some time we, the actors, directors, critics and the members of the audience have been appreciating and at the same time complaining about the plays that are being staged in Calcutta in the languages that are being practiced in Calcutta, be it in Hindi, English, Bangla or any other language. We felt that if we, the practitioners should sit down and talk about the various issues that are bothering us, we may be able to solve some of the problems and several issues may be resolved. Often it so happens that the artists take one side and the critics-audience occupies the other. There is a clear division – one group which creates and the other who criticizes. Many a time this proves to be useful and necessary as well. -

Krishnalila in Terracotta Temples of Bengal

Krishnalila in Terracotta Temples of Bengal Amit Guha Independent Researcher Introduction The brick temples of Bengal are remarkable for the intricately sculpted terracotta panels covering their facades. After an initial period of structural and decorative experimentation in the 17th and 18th centuries, there was some standardization in architecture and embellishment of these temples. However, distinct regional styles remained. From the late 18th century a certain style of richly-decorated temple became common, particularly in the districts of Hugli and Howrah. These temples, usually two- storeyed or atchala and with a triple-arched entrance porch, had carved panels arranged in a fairly well-defined format (Figure 1). Ramayana battle scenes occupied the large panels on the central arch frame with other Ramayana or Krishna stories on the side arches. Running all along the base, including the base of the columns, were two distinctive friezes (Figure 2). Large panels with social, courtly, and hunting scenes ran along the bottom, and above, smaller panels with Krishnalila (stories from Krishna's life). Isolated rectangular panels on the rest of the facade had figures of dancers, musicians, sages, deities, warriors, and couples, within foliate frames. This paper is an iconographic essay on Krishnalila stories in the base panels of the late-medieval terracotta temples of Bengal. The temples of this region are prone to severe damage from the weather, and from rain, flooding, pollution, and renovation. The terracotta panels on most temples are broken, damaged, or completely lost. Exceptions still remain, such as the Raghunatha temple at Parul near Arambagh in Figure 1: Decorated Temple-Facade (Joydeb Kenduli) Hugli, which is unusual in having a well-preserved and nearly-complete series of Krishnalila panels. -

Bengal Patachitra

ojasart.com BENGAL PATACHITRA Ojas is a Sanskrit word which is best transliterated as ‘the nectar of the third eye and an embodiment of the creative energy of the universe’. Ojas endeavours to bring forth the newest ideas in contemporary art. Cover: Swarna Chitrakar Santhal Wedding Ritual, 2018 Vegetable colour on brown paper 28x132 inch 1AQ, Near Qutab Minar Mehrauli, Delhi 110 030 Ph: 85100 44145, +91 11 2664 4145 [email protected] @/#ojasart Bengal Patachitra Works by Anwar Chitrakar 8 Dukhushyam Chitrakar 16 Moyna & Joydeb Chitrakar 24 Swarna Chitrakar 36 Uttam Chitrakar 50 CONTENTS Essays by Ojas Art Award Anubhav R Nath 4 The Mesmerizing Domains of Patta-chittra Prof Neeru Misra 6 Bengal Pata Chitra: Painitng, narrating and singing with twists and turns Prof Soumik Nandy Majumdar 14 Pattachitra of Bengal: An emotion of a community Urmila Banu 34 About the Artists 66 Ojas Art Award rt has a bigger social good is a firm belief and I have seen art at work in changing lives of communities through the economic independence and sustainability that it had Athe potential to provide. A few years ago, I met some accomplished Gond artists in Delhi and really liked their art and the history behind it. Subsequent reading and a visit to Bhopal revealed a lot. The legendary artist J. Swamintahan recognised the importance of the indigenous arts within the contemporary framework, which eventually lead to the establishment and development of institutions like Bharat Bhavan, IGRMS and Tribal Museum. Over the decades, may art forms have been lost to time and it is important to keep the surviving ones alive. -

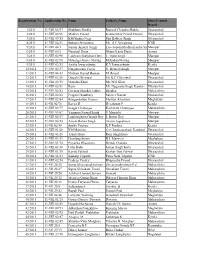

2011 Batch List of Previous Batch Students.Xlsx

Registration_No Application No. Name Father's Name State/Central Board 1/2011 11-VIII 02/97 Shubham Shukla Ramesh Chandra Shukla Uttaranchal 2/2011 11-VIII 02/96 Madhav Prasad Kamleshwar Prasad Painuli Uttaranchal 3/2011 11-VIII 03/15 KM Shikha Negi Shri Balbeer Singh Uttaranchal 4/2011 11-VIII 04/21 Suhasni Srivastava Mr. S.C Srivastava ICSE 5/2011 11-VIII 04/3 Sapam Amarjit Singh Late Sapam Modhuchandra SinghManipur 6/2011 11-VIII 04/2 Nurutpal Dutta Ghana Kanta Dutta Assam 7/2011 11-VIII 02/98 Laishram Bidyabati Devi L. Bijen Singh Manipur 8/2011 11-VIII 02/90 Makunga Joysee Maring M.Kodun Maring Manipur 9/2011 11-VIII 02/33 Anitha Iswarankutty K.V Iswarankutty Kerala 10/2011 11-VIII 02/37 Ningthoujam Victor N. Hemajit Singh Manipur 11/2011 11-VIII 04/13 Maibam Kamal Hassan M. Iboyal Manipur 12/2011 11-VIII 03/28 Dinesh Chhimwal Mr B.C Chhimwal Uttaranchal 13/2011 11-VIII 03/35 Manisha Khati Mr. M.S Khati Uttaranchal 14/2011 11-VIII 02/81 Rajni Mr. Nagendra Singh Kandari Uttaranchal 15/2011 11-VIII 02/82 Gajanan Shankar Jadhav Shankar Maharashtra 16/2011 11-VIII 02/83 Pragati Chaudhary Sanjeev Kumar Uttaranchal 17/2011 11-VIII 02/84 Ritngenbahun Hoojon Markus Kharbhoi Meghalaya 18/2011 11-VII 02/76 Kavya D Devadasan P Kerala 19/2011 11-VIII 02/77 Sougat Chatterjee Kashinath Chatterjee Maharashtra 20/2011 11-VIII 02/67 Yumnam Nirmal Singh Y Manaobi Manipur 21/2011 11-VIII 04/17 Laiphangbam Gunajit Roy L Iboton Roy Manipur 22/2011 11-VIII 04/14 Amom Rohen Singh Amom Jugeshwor Manipur 23/2011 11-VII 02/48 Sruthy Poulose K P Poulose Kerala -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

Wedding Videos

P1: IML/IKJ P2: IML/IKJ QC: IML/TKJ T1: IML PB199A-20 Claus/6343F August 21, 2002 16:35 Char Count= 0 WEDDING VIDEOS band, the blaring recorded music of a loudspeaker, the References cries and shrieks of children, and the conversations of Archer, William. 1985. Songs for the bride: wedding rites of adults. rural India. New York: Columbia University Press. Most wedding songs are textually and musically Henry, Edward O. 1988. Chant the names of God: musical cul- repetitive. Lines of text are usually repeated twice, en- ture in Bhojpuri-Speaking India. San Diego: San Diego State abling other women who may not know the song to University Press. join in. The text may also be repeated again and again, Narayan, Kirin. 1986. Birds on a branch: girlfriends and wedding songs in Kangra. Ethos 14: 47–75. each time inserting a different keyword into the same Raheja, Gloria, and Ann Gold. 1994. Listen to the heron’s words: slot. For example, in a slot for relatives, a wedding song reimagining gender and kinship in North India. Berkeley: may be repeated to include father and mother, father’s University of California Press. elder brother and his wife, the father’s younger brother and his wife, the mother’s brother and his wife, paternal KIRIN NARAYAN grandfather and grandmother, brother and sister-in-law, sister and brother-in-law, and so on. Alternately, in a slot for objects, one may hear about the groom’s tinsel WEDDING VIDEOS crown, his shoes, watch, handkerchief, socks, and so on. Wedding videos are fast becoming the most com- Thus, songs can be expanded or contracted, adapting to mon locally produced representation of social life in the performers’ interest or the length of a particular South Asia. -

Download (5.2

c m y k c m y k Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers of India: Regd. No. 14377/57 CONTRIBUTORS Dr. Karan Singh Gouranga Dash Madhavilatha Ganji Meena Naik Prof. S. A. Krishnaiah Sampa Ghosh Satish C. Mehta Usha Mailk Utpal K Banerjee Indian Council for Cultural Relations Hkkjrh; lkaLdfrd` lEca/k ifj”kn~ Phone: 91-11-23379309, 23379310, 23379314, 23379930 Fax: 91-11-23378639, 23378647, 23370732, 23378783, 23378830 E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.iccrindia.net c m y k c m y k c m y k c m y k Indian Council for Cultural Relations The Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR) was founded on 9th April 1950 by Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, the first Education Minister of independent India. The objectives of the Council are to participate in the formulation and implementation of policies and programmes relating to India’s external cultural relations; to foster and strengthen cultural relations and mutual understanding between India and other countries; to promote cultural exchanges with other countries and people; to establish and develop relations with national and international organizations in the field of culture; and to take such measures as may be required to further these objectives. The ICCR is about a communion of cultures, a creative dialogue with other nations. To facilitate this interaction with world cultures, the Council strives to articulate and demonstrate the diversity and richness of the cultures of India, both in and with other countries of the world. The Council prides itself on being a pre-eminent institution engaged in cultural diplomacy and the sponsor of intellectual exchanges between India and partner countries.