Morales in Plasencia and ” New ” Works Form His Early Compositional Period Cristina Diego Pacheco

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

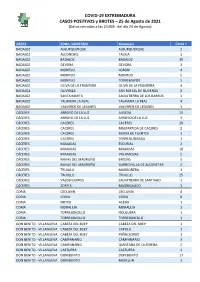

210825 Datos Covid- 19 EXT.Casos+ Y Brotes

COVID-19 EXTREMADURA CASOS POSITIVOS y BROTES – 25 de Agosto de 2021 (Datos cerrados a las 24:00h. del día 24 de Agosto) AREAS ZONA_SANITARIA Municipio Casos + BADAJOZ ALBURQUERQUE ALBURQUERQUE 2 BADAJOZ ALCONCHEL TALIGA 1 BADAJOZ BADAJOZ BADAJOZ 35 BADAJOZ GEVORA GEVORA 1 BADAJOZ MONTIJO LOBON 4 BADAJOZ MONTIJO MONTIJO 5 BADAJOZ MONTIJO TORREMAYOR 5 BADAJOZ OLIVA DE LA FRONTERA OLIVA DE LA FRONTERA 4 BADAJOZ OLIVENZA SAN RAFAEL DE OLIVENZA 2 BADAJOZ SANTA MARTA SALVATIERRA DE LOS BARROS 1 BADAJOZ TALAVERA LA REAL TALAVERA LA REAL 4 BADAJOZ VALVERDE DE LEGANES VALVERDE DE LEGANES 1 CÁCERES ARROYO DE LA LUZ ALISEDA 19 CÁCERES ARROYO DE LA LUZ ARROYO DE LA LUZ 3 CÁCERES CACERES CACERES 20 CÁCERES CACERES MALPARTIDA DE CACERES 2 CÁCERES CACERES SIERRA DE FUENTES 1 CÁCERES CACERES TORREQUEMADA 1 CÁCERES MIAJADAS ESCURIAL 2 CÁCERES MIAJADAS MIAJADAS 10 CÁCERES MIAJADAS VILLAMESIAS 2 CÁCERES NAVAS DEL MADROÑO BROZAS 3 CÁCERES NAVAS DEL MADROÑO GARROVILLAS DE ALCONETAR 2 CÁCERES TRUJILLO MADROÑERA 1 CÁCERES TRUJILLO TRUJILLO 25 CÁCERES VALDEFUENTES SALVATIERRA DE SANTIAGO 1 CÁCERES ZORITA MADRIGALEJO 1 CORIA CECLAVIN CECLAVIN 4 CORIA CORIA CORIA 9 CORIA HOYOS ACEBO 1 CORIA MORALEJA MORALEJA 1 CORIA TORREJONCILLO HOLGUERA 1 CORIA TORREJONCILLO TORREJONCILLO 1 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA CABEZA DEL BUEY CABEZA DEL BUEY 1 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA CABEZA DEL BUEY CAPILLA 1 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA CABEZA DEL BUEY PEÑALSORDO 1 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA CAMPANARIO CAMPANARIO 3 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA CAMPANARIO QUINTANA DE LA SERENA 2 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA CASTUERA CASTUERA 1 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA DON BENITO DON BENITO 17 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA DON BENITO MEDELLIN 1 COVID-19 EXTREMADURA CASOS POSITIVOS y BROTES – 25 de Agosto de 2021 (Datos cerrados a las 24:00h. -

Juan Rebollo Bote

JUAN REBOLLO BOTE SITUACIÓN ACTUAL Investigador predoctoral. Departamento de Historia Antigua y Medieval de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la Universidad de Valladolid (2015 – actualidad). Tesis doctoral: “Entre lo islámico y lo castellano: las comunidades mudéjares en las fronteras de la Corona de Castilla. La región de Extremadura”. Programa de doctorado: “Europa y el mundo atlántico: Poder, cultura y sociedad”. Instituto Universitario de Historia Simancas – Universidad de Valladolid. Miembro del proyecto de investigación: "Estudio de los espacios rituales mudéjares en la Castilla medieval: Mezquitas y cementerios islámicos en una sociedad cristiana" (MINECO HAR2017-83004-P) (actualidad – 2020). Guía oficial de turismo de la Junta de Extremadura (2016-actualidad). Miembro cofundador del colectivo Guías-Historiadores de Extremadura (2016-actualidad). FORMACIÓN ACADÉMICA Licenciado en Historia (Universidad de Salamanca, 2012) Máster interuniversitario en Historia Medieval de Castilla y León (Universidad de Salamanca – Universidad de Valladolid, 2013) PUBLICACIONES: (En prensa) - REBOLLO BOTE, J., “La Escuela de Toledo, entre dos mundos (siglos XI-XII)”, en Libro Homenaje al Profesor Juan Antonio Bonachía. Universidad de Valladolid. (2018) - REBOLLO BOTE, J., “En la frontera: el poblamiento islámico de Extremadura antes y después de la Raya con Portugal”, en eHumanista, Minorías en la España medieval y moderna: asimilación, y/o exclusión (siglos XV al XVII), Amrán, R. y Cortijo, A. (eds.), pp. 61-75. (2018) - REBOLLO BOTE, J., y MARÍN, C. “Guías-Historiadores en centros monumentales: Reflexiones sobre Cáceres, Ciudad Patrimonio de la Humanidad”, Cultural Routes and Heritage Toruism and Rural Development, Book of Proceedings (Cáceres, February 27-28, 2018), Publishing House of the Research and Innovation in Education Institute, Czestochowa, pp 17-24. -

Late German Gothic Methods of Vault Design and Their Relationships with Spanish Ribbed Vaults

Late German Gothic Methods of Vault Design and Their Relationships with Spanish Ribbed Vaults Rafael Martín Talaverano, Carmen Pérez de los Ríos, Rosa Senent Domínguez Polytechnic University of Madrid, Spain Despite the differences among the Late Gothic The vault of the Antigua Chapel has two vaults in different European countries in the striking characteristics: the first is the design of 15th century, masons travelled throughout the the vault plan, which is divided in four rectangles, continent, maintaining an ongoing exchange each reproducing a tierceron ribbed vault with among the different lodges. The Spanish case five keystones;2 the second is the aforementioned is particularly significant, as a great number of ribs that intersect in the tas-de-charge. These two masons from Europe arrived to Spain during the charac teristics can also be found in one of the 1440s and 1450s; for instance, Pedro Guas from vaults illustrated in the Codex Miniatus 3. Brittany and the Coeman family from Brussels Research work on Late Gothic vault construc- settled in Toledo, while Juan de Colonia travelled tion is usually restricted to a single country or from Cologne to Burgos. These masters brought region, and no comparative studies have been with them the advanced knowledge and the tech- carried out in order to prove a potential transfer nological improvements used in Their countries, of knowledge. This present paper, which com- which would appear in the vaults created in Spain pares a German-appearing Spanish vault with the from that moment on. This hypothesis is sup- theoretical German vault construction system, is ported by the fact that some Late Gothic vault intended as a starting point for further research models found in central Europe were also used on this field. -

Francij'co Correa De Arauxo New Light on Hij' Career

FranciJ'co Correa de Arauxo New Light on hiJ' career Robert Stevenson Foundations 01 Correa's Fame. Grove's Dicticmary (1954, 11,455), Baker's Biographical Dictionary (1957, page 322), the Higinio Anglés-Joaquín Pena Diccionario de la música Labor (1954, 1,592-593), and Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart (1952, 11, 1691) unite in decreeing Francisco Correa de Arauxo (= Araujo) to have been a brilliant revolutionary who reveled in new dissonances, in calling him one oí the paramount composers of the Spanish baroque, and in rank ing him as by aII odds "the most important organist between Cabezon and Cabanilles". To paraphase Anglés-Pena: Correa de Arauxo was at heart a firebrand who combed the cJassics [Nicholas Wollick 1 = Volcyr (ca. 148O-ca. 1541), Fran cisco Salinas, Francisco de Montanos and Pietro Cerone among theorists; Josquin des Prez, Nicolas Gombert, Cristóbal de Mo rales, Antonio and Hernando Cabezón, Diego del Castillo, Jeró• nimo or Francisco Peraza, and Manuel Rodrigues Coelho among practitioners] searching for exceptional procedures in order to justify his own novelties. In his preface, Correa de Arauxo prom ised to speed along the progress of Spanish organ music by delivering to thc press other treatises, which however he seems never to have had an opportunity to publish. His music com bines originality with geniality. Even though fulIy conversant with prior [Peninsular] composers and eager to imitate them, he so delighted in new and daring discoveries that he stands. at a remove from both his distinguished predecessors and contem poraries. As a result, he takes pride of place as the most revolu tionary and talented organist oí his epoch in Spain .. -

Centros De Interpretación, Museos Y Otros Recursos

PUNTOS DE INFORMACIÓN ACREDITADOS DEL PARQUE NACIONAL DE MONFRAGÜE CASAS DE MILLÁN Casa de Cultura de Casas de Millán Tfno.: 927 306 257 CASAS DE MIRAVETE GeoCentro Monfragüe Tfno.: 927 542 530 14 CASATEJADA 7 Bar "La Fragua" Tfno.: 927 547 432 CENTRO NEURÁLGICO DELEITOSA 4 Estación de Servicio “Ventilla del Camionero” Tfno.:927 540 238 13 6 JARAICEJO 1, 2 y 3 Hostal-Restaurante Puerta de Monfragüe Tfno.: 927 336 153 / 695 240 625 HIGUERA 9,10, 11 y 12 Centro Actividades sobre las Abejas y la Biodiversidad Tfno.: 927 198 992 8 5 MALPARTIDA DE PLASENCIA Camping-Bungalows Monfragüe Tfno.: 927 459 233 MIRABEL Bar-Centro Social Tfno.: 630 666 751 ROMANGORDO Centro de Interpretación " La Casa de los Aromas" Tfno.: 664 659 872 SAUCEDILLA Oficina Parque Ornitológico Arrocampo Tfno.: 673 440 008 SERRADILLA Centro Interpretación la Huella del Hombre Tfno.: 927 407 002 Centros de Interpretación, SERREJÓN La Tienda de Serrejón Tfno.: 927 547 720 TORIL museos Centro de Interpretación "Pórtico de Monfragüe" Tfno.: 927 577 191 TORREJÓN EL RUBIO Oficina de Turismo de Torrejón el Rubio Tfno.: 927 455 292 y otros recursos VILLARREAL DE SAN CARLOS Centro de Visitantes del P. N. de Monfragüe Tfno.: 927 199 134 en el Parque Nacional Parque Nacional de Monfragüe 10695 Villarreal de San Carlos (Cáceres) Tel. +34 927 19 91 34 Fax +34 927 19 82 12 www.magrama.gob.es/es/red-parques-nacionales/ www.extremambiente.es de Monfragüe [email protected] Parque Nacional y Reserva de la Biosfera de Monfragüe 0 PRESENTACIÓN 1 C.I. -

Datos Covid-19 De Los Pueblos Y Ciudades De Extremadura

COVID-19 EXTREMADURA CASOS POSITIVOS y BROTES – 20 de Agosto de 2021 (Datos cerrados a las 24:00h. del día 19 de Agosto) AREA ZONA_SANITARIA Municipio Casos + BADAJOZ ALCONCHEL TALIGA 4 BADAJOZ BADAJOZ BADAJOZ 37 BADAJOZ JEREZ DE LOS CABALLEROS JEREZ DE LOS CABALLEROS 1 BADAJOZ MONTIJO MONTIJO 4 BADAJOZ OLIVA DE LA FRONTERA ZAHINOS 2 BADAJOZ PUEBLONUEVO DEL GUADIANA PUEBLONUEVO DEL GUADIANA 3 BADAJOZ SAN VICENTE DE ALCANTARA SAN VICENTE DE ALCANTARA 1 BADAJOZ SANTA MARTA ENTRIN BAJO 2 BADAJOZ SANTA MARTA SANTA MARTA 5 BADAJOZ TALAVERA LA REAL TALAVERA LA REAL 2 BADAJOZ VALVERDE DE LEGANES VALVERDE DE LEGANES 1 CÁCERES ALCUESCAR ARROYOMOLINOS 1 CÁCERES ARROYO DE LA LUZ ALISEDA 14 CÁCERES ARROYO DE LA LUZ ARROYO DE LA LUZ 6 CÁCERES CACERES CACERES 54 CÁCERES CACERES TORREORGAZ 11 CÁCERES CASAR DE CÁCERES CASAR DE CACERES 1 CÁCERES GUADALUPE ALIA 3 CÁCERES GUADALUPE GUADALUPE 1 CÁCERES MIAJADAS MIAJADAS 20 CÁCERES MIAJADAS PIZARRO 1 CÁCERES TRUJILLO JARAICEJO 1 CÁCERES TRUJILLO MADROÑERA 1 CÁCERES TRUJILLO PLASENZUELA 1 CÁCERES TRUJILLO TORRECILLAS DE LA TIESA 4 CÁCERES TRUJILLO TRUJILLO 3 CORIA CORIA CORIA 6 CORIA HOYOS ACEBO 2 CORIA HOYOS VILLAMIEL 2 CORIA VALVERDE DEL FRESNO VALVERDE DEL FRESNO 1 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA CABEZA DEL BUEY CABEZA DEL BUEY 9 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA CAMPANARIO CAMPANARIO 1 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA CAMPANARIO QUINTANA DE LA SERENA 2 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA CASTUERA CASTUERA 2 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA CASTUERA MONTERRUBIO DE LA SERENA 1 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA DON BENITO DON BENITO 18 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA HERRERA DEL DUQUE HELECHOSA DE LOS MONTES 1 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA HERRERA DEL DUQUE HERRERA DEL DUQUE 1 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA NAVALVILLAR DE PELA CASAS DE DON PEDRO 1 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA NAVALVILLAR DE PELA NAVALVILLAR DE PELA 4 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA SANTA AMALIA HERNAN CORTES 1 COVID-19 EXTREMADURA CASOS POSITIVOS y BROTES – 20 de Agosto de 2021 (Datos cerrados a las 24:00h. -

Ana Diéguez-Rodríguez the Artistic Relations Between Flanders and Spain in the 16Th Century: an Approach to the Flemish Painting Trade

ISSN: 2511–7602 Journal for Art Market Studies 2 (2019) Ana Diéguez-Rodríguez The artistic relations between Flanders and Spain in the 16th Century: an approach to the Flemish painting trade ABSTRACT Such commissions were received by important workshops and masters with a higher grade of This paper discusses different ways of trading quality. As the agent, the intermediary had to between Flanders and Spain in relation to take care of the commission from the outset to paintings in the sixteenth century. The impor- the arrival of the painting in Spain. Such duties tance of local fairs as markets providing luxury included the provision of detailed instructions objects is well known both in Flanders and and arrangement of shipping to a final destina- in the Spanish territories. Perhaps less well tion. These agents used to be Spanish natives known is the role of Flemish artists workshops long settled in Flanders, who were fluent in in transmitting new models and compositions, the language and knew the local trade. Unfor- and why these remained in use for longer than tunately, very little correspondence about the others. The article gives examples of strong commissions has been preserved, and it is only networks among painters and merchants the Flemish paintings and altarpieces pre- throughout the century. These agents could served in Spanish chapels and churches which also be artists, or Spanish merchants with ties provide information about their workshop or in Flanders. The artists become dealers; they patron. would typically sell works by their business Last, not least it is necessary to mention the partners not only on the art markets but also Iconoclasm revolt as a reason why many high in their own workshops. -

Dossier Informativo

DOSSIER INFORMATIVO ÍNDICE Extremadura Rutas a Motor: a tu aire y en la mejor compañía .......................................... 3 Un destino seguro este verano con productos para todos los públicos ............................... 4 Turismo itinerante, una tendencia al alza ......................................................................... 8 Perfil del turista ..................................................................................................................... 8 Campings ............................................................................................................................... 9 12 rutas a motor y 11 carreteras paisajísticas .................................................................. 10 Ruta 1. Plasencia, Valle del Jerte y La Vera ......................................................................... 10 Ruta 2. Valle del Ambroz y Tierras de Granadilla ................................................................ 10 Ruta 3. Sierra de Gata y Las Hurdes .................................................................................... 10 Ruta 4. Reserva de la Biosfera de Monfragüe ..................................................................... 11 Ruta 5. Cáceres, Trujillo y entorno ...................................................................................... 11 Ruta 6. Guadalupe y Geoparque Villuercas-Ibores-Jara ..................................................... 12 Ruta 7. Reserva de la Biosfera Tajo Internacional .............................................................. -

Ayuntamiento De Malpartida De Plasencia Ayuntamiento

2174 8 Febrero 2007 D.O.E.—Número 16 junto a la carretera N-110, y redactada por el Arquitecto D. Las proposiciones jurídico-económicas y las propuestas de Miguel Ángel Caldera Domínguez, con el objetivo de clasificar convenio se presentarán en plica cerrada con la documentación Suelo Urbanizable para uso industrial en una extensión de prevista en los apartados 2 y 3 del art. 119 de la LSOTEX, 68.570 m2, actualmente clasificados como Suelo No Urbanizable acompañadas de la acreditación de constitución de garantía Protegido. provisional del 3 por 100 del coste previsto de las obras de urbanización. El documento aprobado inicialmente se somete a información pública por un mes contándose a partir del siguiente en que Malpartida de Plasencia, a 30 de enero de 2007. El Alcalde. aparezca inserto el anuncio en el Boletín Oficial de la Provincia o en el Diario Oficial de Extremadura, de conformidad con el art. 77.2.2 de la LSOTEX 15/2001 y art. 128 del R.P. 2159/1978. Pudiendo ser consultado por interesados en la Secretaría del Ayuntamiento a efectos de escritos o reclamaciones. De no presen- AYUNTAMIENTO DE SAUCEDILLA tarse reclamaciones en el plazo de exposición pública, el acuerdo hasta entonces inicial se elevará a provisional. ANUNCIO de 3 de enero de 2007 sobre aprobación inicial del Proyecto de Lo que se hace público para general conocimiento. modificación n.º 2 del Proyecto de Jerte, a 25 de enero de 2007. El Secretario. Delimitación de Suelo Urbano (P.D.S.U.). Aprobado inicialmente, en sesión plenaria celebrada el día 29 de diciembre de 2006, el Proyecto de Modificación Puntual n.º 2 del Proyecto de Delimitación de Suelo Urbano (P.D.S.U.) de Saucedilla AYUNTAMIENTO DE MALPARTIDA DE PLASENCIA (Cáceres), redactado por THUBAN, S.L. -

Listas Definitivas De Centros Admitidos Y Excluidos En La Convocatoria Para

Listas definitivas de centros admitidos y excluidos en la convocatoria para la selección de los centros sostenidos con fondos públicos de niveles previos a la universidad de la Comunidad Autónoma de Extremadura que participarán en el Programa Foro Nativos Digitales durante el curso 2015-16 (Instrucción 24/2015, de la Secretaría General de Educación). CENTROS ADMITIDOS Código Actividades Actividades Actividades Modalidad Nombre Localidad Provincia centro de tipo 1 de tipo 2 de tipo 3 CEIP Santiago PRIM01 06000046 Ahillones Badajoz Sí Sí Sí Ramón y Cajal Sí PRIM02 06006942 CRA Extremadura Alconera Badajoz Sí Sí Sí ESO01 06000381 IES Bembézar Azuaga Badajoz Sí Sí Sí ESO02 06005846 IES Miguel Durán Azuaga Badajoz Sí No Sí COL1 60007210 COL. Santo Ángel Badajoz Badajoz Sí No COL. Santa Teresa Sí COL2 06000770 Badajoz Badajoz Sí Sí de Jesús COL3 06001166 COL. San Atón Badajoz Badajoz Sí No No CEIP Ntra. Sra. De PRIM03 06000502 Badajoz Badajoz Sí No Sí la Soledad IES Virgen de ESO03 06006504 Barcarrota Badajoz Sí No No Soterraño Cabeza del ESO04 06001610 IES Muñoz Torrero Badajoz Sí Sí No Buey IES Virgen de Sí ESO05 10000786 Cáceres Cáceres Sí Sí Guadalupe IES Profesor Sí ESO06 10006910 Cáceres Cáceres Sí No Hernández Pacheco Sí ESO07 06002249 IES Ruta de la Plata Calamonte Badajoz Sí Sí IES Bartolomé J. ESO08 06006693 Campanario Badajoz Sí No No Gallardo ESO09 06011111 IES de Castuera Castuera Badajoz Sí Sí Sí CEIP Virgen de la PRIM04 06001944 Cheles Badajoz Sí No No Luz Sí ESO10 06002080 IES Luis Chamizo Don Benito Badajoz Sí Sí Fuente de Sí ESO11 06007727 IES Alba Plata Badajoz Sí No Cantos PRIM05 10007941 CRA Montellano Garciaz Cáceres Sí No No Gévora del Sí ESO12 06007739 IESO Gévora Badajoz Sí Sí Caudillo Herrera del Sí ESO13 06006528 IES Benazaire Badajoz Sí Sí Duque CEIP Fray Juan de Herrera del PRIM06 06002572 Badajoz Sí No No Herrera Duque CEIP Ntra. -

A Landscape Architectural Design Approach: the Restoration of the Angel Tower and the Cloister of the Cathedral of Cuenca

ISSN: 0214-8293 21 A landscape architectural design approach: The restoration of the Angel Tower and the Cloister of the Cathedral of Cuenca Joaquín Ibáñez Montoya | Maryan Álvarez-Builla Gómez Polytechnic University of Madrid Abstract This article aims to show the recent evolution of concepts such as Cultural Heritage, by offering a survey of the archi - tectural restoration project methodology of the Cuenca Cathedral. The Charters of Athens , from1931 and 1933, –the bases of modernity – converge today after almost a century of leading separate paths: land planning and cultural inter - pretation, space and time recuperate a meeting point, which should have never been lost. The article basically assesses the potential contemporary projects on heritage constructions can offer when studied as a landscape journey. In order to certify the transformations from the present context, the singular monument of Cuenca Cathedral is taken as a mo - del. Its stone materiality provides a memory of secular morphology and clear technical and social wealth. This model unfolds as a dialogue between Theory and Practice reflected on its conservation works. After thirty years of restoration experience on the building performed by the authors, the two last interventions are thoroughly commented in this ar - ticle revealing a new strategy in the architectural project performance. Keywords : architectural project, cultural heritage, landscape, cathedral, Cuenca. Resumen Este artículo trata de analizar la reciente evolución de los conceptos sobre intervención en el Patrimonio Cultural. Para ello utiliza como modelo el proyecto metodológico aplicado sobre las dos últimas actuaciones efectuadas en la Catedral de Cuenca. La Carta de Atenas , 1931, que estableció las bases de la modernidad sobre las dos trayectorias de espacio y tiempo, concuerdan hoy después de casi un siglo, recuperando su punto de encuentro. -

Guide to the City of Palencia

Spain Palencia CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 TRIPS ROUND THE CITY The cathedral district 4 The sights of Palencia 7 Other places of interest 9 IRELAND TRIPS ROUND THE PROVINCE Dublin The Road to Santiago 10 The Romanesque route 13 From Cerrato to UNITED KINGDOM Tierra de Campos 16 London LEISURE AND SHOWS 19 MAP OF THE PROVINCE 22 USEFUL INFORMATION 24 Paris Ca ntab rian FRANCE Sea n a e c O c ti n a tl A F F PALENCIA Lisbon Madrid PORTUGAL Sea ranean diter SPAIN Me C TURESPAÑA Secretaría de Estado de Comercio y Turismo Ministerio de Economía Ceuta Text: Javier Tomé Translation: Hilary Dyke Melilla Photographs: Turespaña Picture Library Design: PH color, S.A. MOROCCO Printed by: Gaez, S.A. Rabat D. L.: M-28473-2001 NIPO: 380-01-033-6 Printed in Spain First edition OVIEDO 130 Km SAN VICENTE DE LA BARQUERA 76 Km SANTANDER 61 Km Pontón 1290 1609 Escudo San Glorio CANTABRIACorconte 1011 Motorway Peña Prieta 2175 Palombera Emb. del Barriedo Espinilla 1260 Riaño 2536 Piedrasluengas ALTO Ebro ExpresswayPuebla de la Reina Casavegas de Lillo Camasobres CAMPOO National road Emb. de Cardaño Riaño Boca de Reinosa Km LOGROÑO 115 Primary basic network road Huérgano de Arriba San Salvador Valdecebollas Secondary basic network road 2450 de Cantamuda Arija Vidrieros 2136 Salcedillo Local road Emb. de Emb. de Cervatos Soncillo Camporredondo Requejada Brañosera Railway Monteviejo Triollo Pozazal Besande Emb. de 1433 Cervera Barruelo 987 Carrales Road to Santiago Cervera-Ruesga Boñar de Santullán 1020 P State Hotel (Parador) Emb. de 1993 de Pisuerga Velilla Salinas Monument Compuerto Matamorisca La Vecilla Peña P Rueda Sabero del Río Carrión Peña del Fraile Redonda Historical ruins 1835 Aviñante Escalada 2450 Emb.