Tourist Mobility at the Destination Toward Protected Areas: the Case-Study of Extremadura

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdfs/ BOE/1938/505/A06178-06181.Pdf (5) Apuntes Históricos De La Universidad De Barcelona (2018)

Revista 2018 DICIEMBRE NÚMERO 12 de Historia de las Vegas Altas —Vegas Altas History Review — Artículos MARINA FATUARTE CORTÉS Reseñando a López Prudencio: “Relieves antiguos” en “Correo de la mañana”, Badajoz, 1925 CRISTIAN GALLEGO MARTÍN-ROMO; ESTEBAN CRUZ HIDALGO Autarquía y condiciones laborales: las reglamentaciones nacionales de trabajo durante el primer franquismo DANIEL CORTÉS GONZÁLEZ Apuntes históricos sobre los Centros de Enseñanza en Don Benito (1885-1977) JESÚS SECO GONZÁLEZ Dimensión social del regadío y la colonización de Vegas Altas Memoria Viva MARÍA JOSÉ SERRANO SUÁREZ Entrevista a Alberto Muñoz Pérez de las Vacas Natushistoria MARÍA INMACULADA FERNÁNDEZ MARTIN; NOELIA RANGEL PRECIADO La Dehesa extremeña. Un recurso didáctico Turismo por... DAVID MARTÍN BERMEJO El Valle de Alagón. Un lugar por descubrir Apartado Literario-Narrativo MARÍA JOSÉ FERNÁNDEZ SÁNCHEZ Viaje a la eternidad FRANCISCO VALDÉS NICOLAU Un delicado y doloroso tema Rincón del Pasado Imágenes para el recuerdo Facsímil: Carta de privilegio del título de Villa a Don Benito (1735) Reseñas Bibliográficas 12 Revista de Historia de las Vegas Altas - Vegas Altas History Review Nº 12 (Diciembre 2018) Una edición del Grupo de Estudios de las Vegas Altas (GEVA) ISSN: 2253-7287 Editada en Don Benito. Disponible online en https://revistadehistoriadelasvegasaltas.com Revista de la Asociación “Torre Isunza” para la Defensa del Patrimonio Histórico y Cultural de Don Benito (http://asociaciontorreisunza.wordpress.com). E-mail de contacto: [email protected] -

Plan Turístico Extremadura 2017-2020

PLAN TURÍSTICO DE EXTREMADURA 2017-2020 Mirador de la memoria. El Torno. Valle del Jerte (Cáceres) 1 PLAN TURÍSTICO 2017 DE EXTREMADURA 2020 2 PLAN TURÍSTICO DE EXTREMADURA 2017-2020 SOCIAL MEDIA turismoextremadura.com @Extremadura_Tur ExtremaduraTurismo Extremadura_Tur Turismo Extremadura Edita: Dirección General de Turismo Consejería de Economía e Infraestructuras Junta de Extremadura 3 PLAN TURÍSTICO 2017 DE EXTREMADURA 2020 4 PLAN TURÍSTICO DE EXTREMADURA 2017-2020 El Plan Turístico de Extremadura 2017-2020, estoy convencido –así lo piensa el sector, así lo piensan los agentes sociales y económicos–, será una herramienta útil para alcanzar las metas que nos hemos propuesto, en la medida en que seamos capaces de sumar esfuerzos para mejorar la calidad, para impulsar la diferenciación y la innovación de nuestros productos y servicios turísticos. La política turística, como cualquier otro sector económico, requiere de tres elementos para actuar sobre él: conocimiento, acuerdo y planificación. Estos son los tres pilares con los que hemos trabajado para este Plan Turístico. Porque en el sector turístico se da una circunstancia singular, la actividad turística se configura a partir de bienes públicos, en muchos casos, sobre recursos territoriales, culturales, ambientales que dependen, en buena medida, de la actuación pública. Por tanto, aquí, más que en ningún otro campo, son necesarias la colaboración interadministrativa y la colaboración público-privada. Estamos ante un sector de futuro que tiene por delante retos como la calidad, la innovación, la accesibilidad y la sostenibilidad. Así, este Plan José Luis Turístico pone el énfasis en acompañar a las empresas para generar empleo, ganar tamaño y competitividad, atender nuevas demandas Navarro e implementar las nuevas tecnologías. -

Los Pteridófitos De Las Villuercas (Cáceres)

Los pteridófitos de Las Villuercas (Cáceres) por S. RIVAS-MARTÍNEZ & M. LADERO Anales Inst. Bot. A. J. Cavanilles, 28: 35-62 (1971) (Pub. 4-IV-1972) Introducción La zona estudiada por nosotros en este trabajo comprende un ma- cizo montañoso, precisamente el central, de los Montes Oretanos. Estas montañas, denominadas también por LAUTEXSACH (1907: 26) Montes de Toledo, están formadas por una serie de alineaciones de sierras cuarcíticas inconexas, cuya cota máxima se halla en la Sierra de Guadalupe, justamente en el Alto de la Villuerca (1.601 m). Los Montes Oretanos o de Toledo, situados en la submeseta meri- dional entre las depresiones de los ríos Tajo y Guadiana, tienen una longitud de unos 340 km. Tienen su punto de arranque en La Mancha (Sierras de los Yébenes y de Herencia), para finalizar más allá de la frontera portuguesa en la Sierra de San Mamede (1.025 m). Desde un punto de vista fitogeográfico Las Villuercas, así como todos los Mon- tes Oretanos, están incluidos en la provincia corológica luso-extrema- durense, que propone RIVAS-MARTÍNEZ (inéd.). En un sentido orográfico escueto, podemos desmembrar la Oreta- na en tres grandes sectores o macizos montañosos. El sector oriental o de los Montes de Toledo en sentido estricto, el central o de Las Vi- lluercas, y el sector occidental o de las Sierras de San Mamede-Mon- tánchez. El sector oriental de la Oretana, separado del central por la Sierra de Altamira (1.316 m), o más estrictamente por la depresión de lo? ríos Guadarranque-Gualija, comprende numerosas sierras, como las de Sevilleja, Hiruela, Fría, Castañar, Los Yébenes, Guadalerzas, Pocito y La Calderina. -

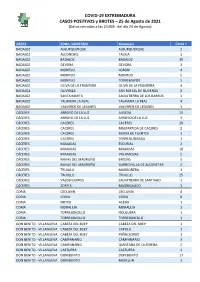

210825 Datos Covid- 19 EXT.Casos+ Y Brotes

COVID-19 EXTREMADURA CASOS POSITIVOS y BROTES – 25 de Agosto de 2021 (Datos cerrados a las 24:00h. del día 24 de Agosto) AREAS ZONA_SANITARIA Municipio Casos + BADAJOZ ALBURQUERQUE ALBURQUERQUE 2 BADAJOZ ALCONCHEL TALIGA 1 BADAJOZ BADAJOZ BADAJOZ 35 BADAJOZ GEVORA GEVORA 1 BADAJOZ MONTIJO LOBON 4 BADAJOZ MONTIJO MONTIJO 5 BADAJOZ MONTIJO TORREMAYOR 5 BADAJOZ OLIVA DE LA FRONTERA OLIVA DE LA FRONTERA 4 BADAJOZ OLIVENZA SAN RAFAEL DE OLIVENZA 2 BADAJOZ SANTA MARTA SALVATIERRA DE LOS BARROS 1 BADAJOZ TALAVERA LA REAL TALAVERA LA REAL 4 BADAJOZ VALVERDE DE LEGANES VALVERDE DE LEGANES 1 CÁCERES ARROYO DE LA LUZ ALISEDA 19 CÁCERES ARROYO DE LA LUZ ARROYO DE LA LUZ 3 CÁCERES CACERES CACERES 20 CÁCERES CACERES MALPARTIDA DE CACERES 2 CÁCERES CACERES SIERRA DE FUENTES 1 CÁCERES CACERES TORREQUEMADA 1 CÁCERES MIAJADAS ESCURIAL 2 CÁCERES MIAJADAS MIAJADAS 10 CÁCERES MIAJADAS VILLAMESIAS 2 CÁCERES NAVAS DEL MADROÑO BROZAS 3 CÁCERES NAVAS DEL MADROÑO GARROVILLAS DE ALCONETAR 2 CÁCERES TRUJILLO MADROÑERA 1 CÁCERES TRUJILLO TRUJILLO 25 CÁCERES VALDEFUENTES SALVATIERRA DE SANTIAGO 1 CÁCERES ZORITA MADRIGALEJO 1 CORIA CECLAVIN CECLAVIN 4 CORIA CORIA CORIA 9 CORIA HOYOS ACEBO 1 CORIA MORALEJA MORALEJA 1 CORIA TORREJONCILLO HOLGUERA 1 CORIA TORREJONCILLO TORREJONCILLO 1 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA CABEZA DEL BUEY CABEZA DEL BUEY 1 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA CABEZA DEL BUEY CAPILLA 1 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA CABEZA DEL BUEY PEÑALSORDO 1 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA CAMPANARIO CAMPANARIO 3 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA CAMPANARIO QUINTANA DE LA SERENA 2 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA CASTUERA CASTUERA 1 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA DON BENITO DON BENITO 17 DON BENITO - VILLANUEVA DON BENITO MEDELLIN 1 COVID-19 EXTREMADURA CASOS POSITIVOS y BROTES – 25 de Agosto de 2021 (Datos cerrados a las 24:00h. -

Santiago Del Campo Una Villa Histórica En La Penillanura

SANTIAGO DEL CAMPO UNA VILLA HISTÓRICA EN LA PENILLANURA CACEREÑA José Antonio Ramos Rubio Óscar de San Macario Sánchez A don Santos Palomero, párroco de Santiago del Campo I.- PRÓGOLO II.- INTRODUCCIÓN III.- EL MEDIO NATURAL IV.- LA HISTORIA V.- OBRAS ARTÍSTICAS 1.- LA IGLESIA PARROQUIAL 2.- LA ERMITA DE LA SOLEDAD 3.- LA ERMITA DE SAN MARCOS 4.- ERMITAS DESAPARECIDAS VI.- LA CULTURA POPULAR 1.- LAS CANDELAS 2.- LA ROMERIA DE SAN MARCOS 3.- FIESTAS DE AGOSTO 4.- EL CRISTO DE LOS NARANJOS I.- PRÓLOGO Nuestra bibliografía artística e histórica ha sido precaria hasta hace bien pocos años. Los datos documentales acopiados por eruditos no tenían, muchas veces, corroboración con las obras a que se referían y faltaban visiones de conjunto que profundizase en el conocimiento de autores, formas y épocas. Especial interés han apostado en el estudio de esta obra por parte de sus autores, José Antonio y Oscar, por ser nuestra población una de las menos estudiadas de la provincia de Cáceres y que cuenta con un importante pasado histórico y un importante elenco de obras artísticas. El libro, es un auténtico alarde de esmerada impresión y profusión de imágenes, junto con un texto lleno de notas anecdóticas, datos de gran interés artístico, y un contenido bien enfocado sobre la historia de Santiago del Campo, llena la laguna, creada por la falta actual de una amplia descripción histórico artística de la población. Todo este acervo, reunido en pocos meses, se caracteriza por el análisis inmediato, el rigor en los datos, su hábil selección y su presentación clara y atrayente por parte de los autores de este libro. -

Cto Extremadura Infantil-Junior Don Benito, 25 - 26/1/2020

CTO EXTREMADURA INFANTIL-JUNIOR DON BENITO, 25 - 26/1/2020 Prueba 22 Fem., 200m Libre 13 - 17 años 26/01/2020 - 10:43 Listado de inscrito REX 1:59.08 FÁTIMA GALLARDO CARAPETO CASTELLON 29/11/2013 MME 17 1:59.14 FÁTIMA GALLARDO CARAPETO X 01/01/2014 MME 16 1:59.08 FÁTIMA GALLARDO CARAPETO X 01/01/2013 MME 15 2:02.63 FÁTIMA GALLARDO CARAPETO X 01/01/2012 MME 14 2:01.94 FÁTIMA GALLARDO CARAPETO X 01/01/2011 MME 13 2:12.80 FÁTIMA GALLARDO CARAPETO X 01/01/2010 MINIMAS 2007 13: 2:40.00 / MÍNIMAS 2003 17: 2:40.00 / MÍNIMAS 2004 16: 2:43.50 / MÍNIMAS 2005 15: 2:48.00 / MÍNIMAS 2006 14: 2:52.00 Introducir conversión: ESP:Conversion Spanish Rules LICENCIA NOMBRE AÑO CLUB M. REAL PISC M. CONV FECHA LUGAR 1 1108394 SANCHEZ-MIRANDA CABANILLAS A.2005 C.N. Don Benito Acuarun 2:09.70 25m S 2:09.70 22/12/2019 CÁCERES 2 1127489 PEDROSA MOLERO Clara 2004 El Perú Cáceres Wellness 2:10.00 25m S 2:10.00 22/12/2019 CÁCERES 3 1089022 MARTIN BECERRA Ana Maria 2003 C.N. Almendralejo 2:10.61 25m S 2:10.61 18/05/2019 CACERES 4 1100670 GARCIA SANTOS Andrea 2004 C.N. Plasencia 2:11.41 25m S 2:11.41 22/12/2019 CÁCERES 5 1140683 DOMINGUEZ HERNANDEZ Aitana 2005 C.N. Plasencia 2:12.61 25m S 2:12.61 05/05/2019 BADAJOZ 6 1089030 MORON ALONSO Beatriz 2004 C.N. -

B.O. DE CÁCERES Página 42 Viernes 9 Octubre 2009

Página 42 Viernes 9 Octubre 2009 - N.º 196 B.O. DE CÁCERES Lo que se hace público, en cumplimiento de lo CAMINOMORISCO preceptuado en el artículo 30 del Reglamento de Acti- vidades Molestas, Insalubres, Nocivas y Peligrosas, Anuncio Decreto 24 14/ 1961, de 30 de noviembre, a fin de que quienes se consideren afectados de algún modo por En cumplimiento de lo establecido en el artículo la actividad de referencia, puedan formular, por escrito, 110.1.f) del Real Decreto 1372/1986, de 26 de noviem- que presentarán en la Secretaría del Ayuntamiento, las bre, del Reglamento de Bienes de las Entidades Loca- observaciones pertinentes, durante el plazo de diez les, y del artículo 86 de la ley 30/1992, de 26 de días hábiles. noviembre, se hace público por plazo de veinte días, a favor de la Junta de Extremadura y para destinarlo a la Almoharín, a 21 de septiembre de 2009.- El Alcalde. construcción de una nueva Base de la Unidad 6315 Medicalizada de Emergencias y Consultorio, el expe- diente de cesión gratuita del bien inmueble solar SERREJÓN situado en C/ Rocandelario 6 (A), para que los intere- sados puedan presentar las alegaciones que estimen Anuncio pertinentes. Por Resolución de la Alcaldía de fecha 5 de octubre En Caminomorisco a 5 de octubre de 2009.- La de 2009 se aprobó la adjudicación provisional del Alcaldesa, M.ª Soledad Gómez Sánchez. contrato de obras de «Instalación alumbrado público 6563 en Serrejón (Cáceres)», lo que se publica a los efectos del artículo 135.3 de la Ley 30/2007, de 30 de octubre, CAMINOMORISCO de Contratos del Sector Público Anuncio 1. -

Calendario Laboral 2021.Qxp M 23/11/20 17:33 Página 1

Calendario Laboral 2021.qxp_M 23/11/20 17:33 Página 1 JUNTA DE EXTREMADURA CALENDARIO LABORAL OFICIAL DE FIESTAS PARA LA Consejería de Educación y Empleo Dirección General de Trabajo COMUNIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE EXTREMADURA AÑO 2021 Y CUADRO HORARIO FIESTAS NACIONALES Y REGIONALES (Decreto 48/2020, de 26 de agosto; D.O.E. nº 170, de 1 de septiembre de 2020) EMPRESA Día 1 de enero: AÑO NUEVO Día 8 de septiembre: DÍA DE EXTREMADURA LOCALIDAD Día 6 de enero: EPIFANÍA DEL SEÑOR Día 12 de octubre: FIESTA NACIONAL DE ESPAÑA Día 19 de marzo: SAN JOSÉ Día 1 de noviembre: TODOS LOS SANTOS ACTIVIDAD N.º TRABAJADORES Día 1 de abril: JUEVES SANTO Día 6 de diciembre: DÍA DE LA CONSTITUCIÓN Día 2 de abril: VIERNES SANTO ESPAÑOLA N.º C.C. DE SEGURIDAD SOCIAL Día 1 de mayo: FIESTA DEL TRABAJO Día 8 de diciembre: INMACULADA CONCEPCIÓN Día 15 de agosto: ASUNCIÓN DE LA VIRGEN Día 25 de diciembre: NATIVIDAD DEL SEÑOR HORARIO DE TRABAJO ENERO FEBRERO MARZO INVIERNO VERANO LMXJVSD LMXJVSD LMXJVSD Desde: Hasta: Desde: Hasta: 1 2 3 1234567 1234567 456 78910 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 LUNES A VIERNES: LUNES A VIERNES: 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Mañana: a Mañana: a 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 29 30 31 Tarde: a Tarde: a ABRIL MAYO JUNIO SÁBADO: a SÁBADO: a LMXJVSD LMXJVSD LMXJVSD DESCANSO: DESCANSO: 123 4 12 123456 567891011 3456789 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 EMPRESAS A TURNOS 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 24 26 27 28 29 30 31 25 26 27 28 29 30 28 29 30 1º JULIO AGOSTO SEPTIEMBRE 2º LMXJVSD LMXJVSD LMXJVSD 3º 1234 1 12345 567891011 2345678 678 9101112 , a de de 2021. -

Censo-Sociedades-Caceres-2015

SOCIEDADES CÁCERES Localidad Denominación ACEUCHE LA COMUNITARIA AHIGAL AHIGAL ALAGON DEL RIO ALAGON DEL RIO ALCANTARA ALCANTARA ALCOLLARIN SANTA CATALINA ALCUESCAR NTRA. SRA. DEL ROSARIO ALDEA MORET ALDEA MORET ALDEACENTENERA EL HALCON ALDEANUEVA DE LA VERA LA MILAGROSA ALIA ALIA ALMARAZ ALMARAZ ARROYO DE LA LUZ VIRGEN DE LA LUZ ARROYOMOLINOS DE LA VERA SAN ROQUE ARROYOMOLINOS DE MONTANCHEZ SAN SEBASTIAN BELVIS DE MONROY EL BERROCAL BERROCALEJO PEÑAFLOR BERZOCANA SAN FULGENCIO Y CABALLERIAS BOHONAL DE IBOR SAN BARTOLOME BROZAS BROZAS CABEZUELA DEL VALLE CABEZUELA DEL VALLE CABRERO SAN MIGUEL CAÑAVERAL LA PERDIZ ROJA CARCABOSO SAN JOVITA CARRASCALEJO RISCO DEL PRADO CASAR DE CACERES VIRGEN DEL PRADO CASAS DE BELVIS LA JARILLA CASAS DE MILLAN LA SOLANA CASATEJADA CAMPO ARAÑUELO CECLAVIN LA NECESARIA CEDILLO CEDILLO CUACOS DE YUSTE YUSTE DELEITOSA LA BREÑA EL GORDO EL PENDON EL TORNO EL TORNO ELJAS EL REBOLLAR ESCURIAL LAS FIÑAS FRESNEDOSO DE IBOR CAMPEROS DEL HELECHAL GARCIAZ DEHESA BOYAL GARGANTA LA OLLA SAN LORENZO GARVIN DE LA JARA LA GARVINA GUADALUPE GUADALUPE GUIJO DE CORIA LOS ARROYOS GUIJO DE SANTA BARBARA REFUGIO VIRGEN DE LAS NIEVES HERGUIJUELA LA UNION HERVAS HERVAS IBAHERNANDO EL IMPERIO JARAIZ DE LA VERA LA DEHESA JARANDILLA DE LA VERA CERROPINO JERTE JERTE LA CUMBRE EL GAMONAL LOGROSAN SAN MATEO LOSAR DE LA VERA EL ENCANTO MADRIGALEJO SAN JUAN BAUTISTA MAJADAS DEL TIETAR EL MAJAEÑO MALPARTIDA DE CACERES LA ZAFRILLA MALPARTIDA DE PLASENCIA MALPARTIDA Y CHINATO MESAS DE IBOR COMUNIDAD MIAJADAS SAN ISIDRO MILLANES DE LA MATA -

El Valle Del Jerte Navaconcejo: Estudio De Los Instrumentos De Protección

EL VALLE DEL JERTE NAVACONCEJO: ESTUDIO DE LOS INSTRUMENTOS DE PROTECCIÓN CONJUNTOS HISTÓRICOS Y PAISAJES CULTURALES II Prof: José Luis García Grinda MÁSTER UNIVERSITARIO EN CONSERVACIÓN Y CURSO 2017 – 2018 RESTAURACIÓN DEL PATRIMONIO ARQUITECTÓNICO Isabel Segovia Campos ESCUELA TÉCNICA SUPERIOR DE ARQUITECTURA DE MADRID CONJUNTOS HISTÓRICOS Y PAISAJES CULTURALES II MÁSTER UNIVERSITARIO EN CONSERVACIÓN Y El Valle del Jerte. Navaconcejo. RESTAURACIÓN DEL PATRIMONIO ARQUITECTÓNICO CURSO 2017 - 2018 ESCUELA TÉCNICA SUPERIOR DE ARQUITECTURA DE MADRID ÍNDICE OBJETO DE ESTUDIO ESTADO DE LA CUESTIÓN 1. INTRODUCCIÓN 1.1. Situación 1.2. Sinopsis Histórica 1.3. Breve caracterización 2. PATRIMONIO ARQUITECTÓNICO 2.1. Elementos declarados BIC 2.2. Elementos catalogados por la Junta de Extremadura 3. REVISIÓN DE LA NORMATIVA 3.1. Normativa vigente: NN.SS., 1997 3.2. Normativa no aprobada: PGM 2011 3.3. Normativa en trámite: PGM, 2017 4. OBSERVACIONES Y PROPUESTAS DE MEJORA CONCLUSIONES BIBLIOGRAFÍA Página 2 | 52 CONJUNTOS HISTÓRICOS Y PAISAJES CULTURALES II MÁSTER UNIVERSITARIO EN CONSERVACIÓN Y El Valle del Jerte. Navaconcejo. RESTAURACIÓN DEL PATRIMONIO ARQUITECTÓNICO CURSO 2017 - 2018 ESCUELA TÉCNICA SUPERIOR DE ARQUITECTURA DE MADRID OBJETO DE ESTUDIO El presente trabajo pretende analizar la normativa que afecta a la vivienda tradicional del Municipio de Navaconcejo, situado en el Valle del Jerte, al norte de la provincia de Cáceres (Extremadura). En general, el Valle del Jerte se caracteriza por su elevado número de construcciones vernáculas, sin embargo, esta se encuentra en peligro pues las nuevas construcciones resultan más atractivas para la población, dejando desocupadas estas viviendas, que son la expresión de una sociedad y un modo de vida adaptado a un emplazamiento particular. -

Juan Rebollo Bote

JUAN REBOLLO BOTE SITUACIÓN ACTUAL Investigador predoctoral. Departamento de Historia Antigua y Medieval de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la Universidad de Valladolid (2015 – actualidad). Tesis doctoral: “Entre lo islámico y lo castellano: las comunidades mudéjares en las fronteras de la Corona de Castilla. La región de Extremadura”. Programa de doctorado: “Europa y el mundo atlántico: Poder, cultura y sociedad”. Instituto Universitario de Historia Simancas – Universidad de Valladolid. Miembro del proyecto de investigación: "Estudio de los espacios rituales mudéjares en la Castilla medieval: Mezquitas y cementerios islámicos en una sociedad cristiana" (MINECO HAR2017-83004-P) (actualidad – 2020). Guía oficial de turismo de la Junta de Extremadura (2016-actualidad). Miembro cofundador del colectivo Guías-Historiadores de Extremadura (2016-actualidad). FORMACIÓN ACADÉMICA Licenciado en Historia (Universidad de Salamanca, 2012) Máster interuniversitario en Historia Medieval de Castilla y León (Universidad de Salamanca – Universidad de Valladolid, 2013) PUBLICACIONES: (En prensa) - REBOLLO BOTE, J., “La Escuela de Toledo, entre dos mundos (siglos XI-XII)”, en Libro Homenaje al Profesor Juan Antonio Bonachía. Universidad de Valladolid. (2018) - REBOLLO BOTE, J., “En la frontera: el poblamiento islámico de Extremadura antes y después de la Raya con Portugal”, en eHumanista, Minorías en la España medieval y moderna: asimilación, y/o exclusión (siglos XV al XVII), Amrán, R. y Cortijo, A. (eds.), pp. 61-75. (2018) - REBOLLO BOTE, J., y MARÍN, C. “Guías-Historiadores en centros monumentales: Reflexiones sobre Cáceres, Ciudad Patrimonio de la Humanidad”, Cultural Routes and Heritage Toruism and Rural Development, Book of Proceedings (Cáceres, February 27-28, 2018), Publishing House of the Research and Innovation in Education Institute, Czestochowa, pp 17-24. -

Mancomunidades Integrales De La Provincia De Cáceres

MANCOMUNIDADES INTEGRALES DE LA PROVINCIA DE CÁCERES La dr Mancomunidades integrales illa Casares de las Hurdes r Campo Arañuelo Nuñomoral o d Comarca de Trujillo a e Robledillo de Gata u Caminomorisco q n Z ra a La Vera f La Pesga r Descargamaría o z in a La Garganta P Casar de Palomero d Ab Baños de Montemayor e a d Las Hurdes G í o Mohedas de Granadilla a T n Torrecilla de los Angeles o r s A Cadalso ervá r s a H n c e s Gata Palomero n a r a e Torre de Don Miguel lj a v F b Cerezo La Granja a Riberos del Tajo E d l o Hernán Pérez Gargantilla J c i e e Santa Cruz de Paniagua l a l d a r s a t r San Martín de Trevejo e Guijo de Granadilla e e Santibáñez el AltoVillanueva de la Sierra A d l Cabezuela del Valle V h Rivera de Fresnedosa r ie J m i a Talaveruela de la Vera Hoyos a e g r lla Villasbuenas de Gata ill l v i a l V Santibáñez el Bajo a Navaconcejo Guijo de Santa Bárbara Madrigal de la Vera a Villa del Campo l e V A d Perales del Puerto ce Villar de Plasencia Rebollar Viandar de la Vera Sierra de Gata Pozuelo de Zarzón itu Aldeanueva de la Vera a na Cabezabellosa l Losar de la Vera v G El Torno a e n u u Oliva de Plasencia r C o Garganta la Olla Valverde de la Vera n ij i a a Sierra de Montánchez o l l Casas del Castañar P l z i a d Valdeobispo Cilleros V Huélaga d e Guijo de Galisteo Barrado Jarandilla de la Vera a i j ll C Cuacos de YusteRobledillo de la Vera e a Montehermoso Sierra de San Pedro l o Carcaboso a r r ia Arroyomolinos de la VeraTorremenga o o e Gargüera de la Vera Collado de la Vera M Casas de Don Gómez t Plasencia