Biological Conservation 219 (2018) 28–34

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution of Angiosperm Pollen. 7. Nitrogen-Fixing Clade1

Evolution of Angiosperm Pollen. 7. Nitrogen-Fixing Clade1 Authors: Jiang, Wei, He, Hua-Jie, Lu, Lu, Burgess, Kevin S., Wang, Hong, et. al. Source: Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 104(2) : 171-229 Published By: Missouri Botanical Garden Press URL: https://doi.org/10.3417/2019337 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non - commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://bioone.org/journals/Annals-of-the-Missouri-Botanical-Garden on 01 Apr 2020 Terms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use Access provided by Kunming Institute of Botany, CAS Volume 104 Annals Number 2 of the R 2019 Missouri Botanical Garden EVOLUTION OF ANGIOSPERM Wei Jiang,2,3,7 Hua-Jie He,4,7 Lu Lu,2,5 POLLEN. 7. NITROGEN-FIXING Kevin S. Burgess,6 Hong Wang,2* and 2,4 CLADE1 De-Zhu Li * ABSTRACT Nitrogen-fixing symbiosis in root nodules is known in only 10 families, which are distributed among a clade of four orders and delimited as the nitrogen-fixing clade. -

Recchia Sessiliflora (Surianaceae Arn.), Una Especie Nueva De La Cuenca Del Balsas En El Estado De Guerrero, México

Acta Botanica Mexicana 108: 1-9 (2014) RECCHIA SESSILIFLORA (SURIANACEAE ARN.), UNA ESPECIE NUEVA DE LA CUENCA DEL BALSAS EN EL ESTADO DE GUERRERO, MÉXICO ANDRÉS GONZÁLEZ-MURILLO¹, RamIRO CRUZ-DURÁN²,³ Y JAIME JIMÉNEZ-RamÍREZ² ¹Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Facultad de Ciencias, Departamento de Ecología, Delegación Coyoacán, 04510 México, D.F., México. ²Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Facultad de Ciencias, Departamento de Biología Comparada, Delegación Coyoacán, 04510 México, D.F., México. ³Autor para la correspondencia: [email protected] RESUMEN Se describe e ilustra a Recchia sessiliflora (Surianaceae Arn.), una especie nueva de la Cuenca del río Balsas en el estado de Guerrero, México. El nuevo taxon es afín a Recchia connaroides (Loes. & Soler) Standl., pero difiere de ella por tener folíolos más pequeños, que aumentan de tamaño hacia el ápice de la hoja, elípticos a suborbiculares, el raquis con alas evidentes, las inflorescencias en espiga y los pétalos oblanceolados con el ápice irregularmente emarginado. Esta especie se conoce hasta ahora solo de la localidad tipo, creciendo en bosque tropical caducifolio. Se presenta una comparación de las características de las especies afines, un mapa de distribución y una clave dicotómica para el reconocimiento de las especies conocidas del género Recchia Moc. & Sessé ex DC. Palabras clave: Cuenca del río Balsas, Guerrero, México, Recchia, Simaroubaceae, Surianaceae. ABSTRACT A new species from the Balsas Depression in the state of Guerrero, Mexico, Recchia sessiliflora (Surianaceae Arn.), is described and illustrated. This new species is similar to Recchia connaroides (Loes. & Soler) Standl., differing from the latter in having smaller, elliptic to suborbicular leaflets which increase in size towards the apex of the leaf, a rachis which is clearly winged, a spicate inflorescence and flowers with oblanceolate and irregularly 1 Acta Botanica Mexicana 108: 1-9 (2014) emarginate petals. -

Ecology Assessment Report

Final Report R3 Ecological Assessment Report (flora) Lot 22 WV1510 November 2012 Origin Energy Document Number: Q-4200-15-RP-1025 flora ecological assess ment – Lot 22 WV1510 ecosure.com.au i Table of Contents Table of Contents .............................................................................................................................................. ii Glossary ............................................................................................................................................................... iii 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Purpose and Scope ................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Limitations .................................................................................................................................... 4 2 Site Context ............................................................................................................................................... 5 3 Methodology ............................................................................................................................................ 6 3.1 Assessment Personnel ................................................................................................................ 6 3.2 Study Area .................................................................................................................................. -

Control of Currant Bush (Carissa Ovata) in Developed Brigalow (Acacia Harpophylla) Country

Tropical Grasslands (1998) Volume 32, 259–263 259 Control of currant bush (Carissa ovata) in developed brigalow (Acacia harpophylla) country P.V. BACK can coalesce to cover large areas that signifi- Queensland Beef Industry Institute, Department cantly reduce pasture production. of Primary Industries, Tropical Beef Centre, Ploughing to control brigalow regrowth Rockhampton, Queensland, Australia (Johnson and Back 1974; Scanlan and Anderson 1981) can control currant bush effectively but is very expensive. A more cost-effective treatment is Abstract needed for areas where currant bush dominates in the absence of brigalow regrowth. This paper reports a study designed to test the effectiveness Currant bush (Carissa ovata) is the major native of 6 mechanical methods and 2 herbicide treat- woody weed invading sown buffel grass pastures ments for controlling currant bush in situations in cleared brigalow (Acacia harpophylla) forests where it is the major weed. in Queensland. Stickraking followed by chisel ploughing is a viable alternative to and is more economical than herbicide treatment and blade Materials and methods ploughing for controlling currant bush. Chisel ploughing following stickraking gives good con- Site trol of currant bush with no detrimental effect on existing buffel grass pasture. Stickraking alone is The experiment was carried out on “Tulloch- not sufficient to control currant bush. Ard”, a commercial cattle grazing property 10 km west of Blackwater in central Queensland (23° 33’ S, 148° 44’ E). The original vegetation Introduction comprised a brigalow — blackbutt (Eucalyptus cambageana) scrub with currant bush present in Currant bush (Carissa ovata) is an erect or the understorey, which was cleared and sown to spreading, intricately branched shrub, 1–2 m tall, buffel grass (Cenchrus ciliaris) in 1988. -

Contributions to the Solution of Phylogenetic Problem in Fabales

Research Article Bartın University International Journal of Natural and Applied Sciences Araştırma Makalesi JONAS, 2(2): 195-206 e-ISSN: 2667-5048 31 Aralık/December, 2019 CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE SOLUTION OF PHYLOGENETIC PROBLEM IN FABALES Deniz Aygören Uluer1*, Rahma Alshamrani 2 1 Ahi Evran University, Cicekdagi Vocational College, Department of Plant and Animal Production, 40700 Cicekdagi, KIRŞEHIR 2 King Abdulaziz University, Department of Biological Sciences, 21589, JEDDAH Abstract Fabales is a cosmopolitan angiosperm order which consists of four families, Leguminosae (Fabaceae), Polygalaceae, Surianaceae and Quillajaceae. The monophyly of the order is supported strongly by several studies, although interfamilial relationships are still poorly resolved and vary between studies; a situation common in higher level phylogenetic studies of ancient, rapid radiations. In this study, we carried out simulation analyses with previously published matK and rbcL regions. The results of our simulation analyses have shown that Fabales phylogeny can be solved and the 5,000 bp fast-evolving data type may be sufficient to resolve the Fabales phylogeny question. In our simulation analyses, while support increased as the sequence length did (up until a certain point), resolution showed mixed results. Interestingly, the accuracy of the phylogenetic trees did not improve with the increase in sequence length. Therefore, this study sounds a note of caution, with respect to interpreting the results of the “more data” approach, because the results have shown that large datasets can easily support an arbitrary root of Fabales. Keywords: Data type, Fabales, phylogeny, sequence length, simulation. 1. Introduction Fabales Bromhead is a cosmopolitan angiosperm order which consists of four families, Leguminosae (Fabaceae) Juss., Polygalaceae Hoffmanns. -

Impacts of Land Clearing

Impacts of Land Clearing on Australian Wildlife in Queensland January 2003 WWF Australia Report Authors: Dr Hal Cogger, Professor Hugh Ford, Dr Christopher Johnson, James Holman & Don Butler. Impacts of Land Clearing on Australian Wildlife in Queensland ABOUT THE AUTHORS Dr Hal Cogger Australasian region” by the Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union. He is a WWF Australia Trustee Dr Hal Cogger is a leading Australian herpetologist and former member of WWF’s Scientific Advisory and author of the definitive Reptiles and Amphibians Panel. of Australia. He is a former Deputy Director of the Australian Museum. He has participated on a range of policy and scientific committees, including the Dr Christopher Johnson Commonwealth Biological Diversity Advisory Committee, Chair of the Australian Biological Dr Chris Johnson is an authority on the ecology and Resources Study, and Chair of the Australasian conservation of Australian marsupials. He has done Reptile & Amphibian Specialist Group (IUCN’s extensive research on herbivorous marsupials of Species Survival Commission). He also held a forests and woodlands, including landmark studies of Conjoint Professorship in the Faculty of Science & the behavioural ecology of kangaroos and wombats, Mathematics at the University of Newcastle (1997- the ecology of rat-kangaroos, and the sociobiology of 2001). He is a member of the International possums. He has also worked on large-scale patterns Commission on Zoological Nomenclature and is a in the distribution and abundance of marsupial past Secretary of the Division of Zoology of the species and the biology of extinction. He is a member International Union of Biological Sciences. He is of the Marsupial and Monotreme Specialist Group of currently the John Evans Memorial Fellow at the the IUCN Species Survival Commission, and has Australian Museum. -

The Roles of the Queensland Herbarium and Its Collections

Proceedings of the 7th and 8th Symposia on Collection Building and Natural History Studies in Asia and the Pacific Rim, edited by Y. Tomida et al., National Science Museum Monographs, (34): 73–81, 2006. The Roles of the Queensland Herbarium and Its Collections Rod J. F. Henderson1, Gordon P. Guymer1 and Paul I. Forster1,2 1Queensland Herbarium, Environmental Protection Agency, Brisbane Botanic Gardens, Mt Coot-tha Road, Toowong, Queensland 4066, Australia (2e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract The roles of the Queensland Herbarium (BRI) and its collections are outlined together with a brief historical account of its founding and subsequent development to the present day. Estab- lished in 1855, the Queensland Herbarium now comprises in excess of 700,000 fully databased botan- ical specimens. The Queensland Herbarium was one of the first herbaria worldwide to database its collections starting in the 1970’s. The Queensland Herbarium (BRI) is the centre for botanical re- search and information on Queensland flora and vegetation communities, and for plant biodiversity research in Queensland’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). It is an integral part of the interna- tional network of herbaria, which facilitates research on the Queensland flora by national and interna- tional researchers. The Herbarium is the principal focus for documenting and monitoring Queens- land’s rare and threatened plants and plant communities, vegetation and regional ecosystem surveys, mapping and monitoring, plant names, plant distribution and identification, taxonomic and ecological research on plants and plant communities within the state. Key words: Queensland Herbarium, BRI, Flora. Introduction The Queensland Herbarium (BRI) commenced in 1855, when Walter Hill was appointed Su- perintendent of the Botanic Gardens in Brisbane. -

005056Ba00a7/A71d58ad-4Cba-48B6

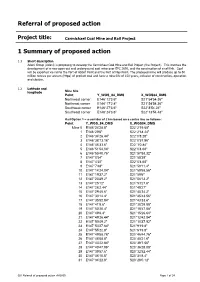

Referral of proposed action Project title: Carmichael Coal Mine and Rail Project 1 Summary of proposed action 1.1 Short description Adani Group (Adani) is proposing to develop the Carmichael Coal Mine and Rail Project (the Project). This involves the development of a new open-cut and underground coal mine over EPC 1690, and the construction of a rail link. Coal will be exported via rail to the Port of Abbot Point and the Port of Hay Point. The proposed mine will produce up to 60 million tonnes per annum (Mtpa) of product coal and have a mine life of 150 years, inclusive of construction, operation and closure. 1.2 Latitude and longitude Mine Site Point Y_WGS_84_DMS X_WGS84_DMS Northwest corner E146°12'3.6" S21°54'54.36" Northeast corner E146°17'2.4" S21°54'54.36" Southwest corner E146°27'3.6" S22°8'54.24" Southeast corner E146°24'3.6" S22°13'54.48" Rail Option 1 – a corridor of 2 km based on a centre line as follows: Point Y_WGS_84_DMS X_WGS84_DMS Mine 0 E146°24'28.8" S22°2'19.68" 1 E146°29'6" S22°2'18.24" 2 E146°34'26.44" S22°0'8.28" 3 E146°38'13.16" S22°0'57.96" 4 E146°46'33.6" S22°1'0.84" 5 E146°51'54.04" S22°0'4.68" 6 E146°55'40.76" S21°57'58.32" 7 E147°0'54" S21°58'39" 8 E147°4'30" S22°0'4.68" 9 E147°7'48" S21°59'11.4" 10 E147°14'24.04" S21°59'58.56" 11 E147°19'37.2" S21°59'6" 12 E147°23'49.2" S21°56'13.2" 13 E147°25'12" S21°53'27.6" 14 E147°26'2.44" S21°48'27" 15 E147°29'45.6" S21°45'34.2" 16 E147°33'14.4" S21°45'43.56" 17 E147°35'52.84" S21°43'33.6" 18 E147°41'9.6" S21°30'29.88" 19 E147°50'20.4" S21°18'47.88" 20 E147°49'8.4" S21°15'26.64" -

Combined Phylogenetic Analyses Reveal Interfamilial Relationships and Patterns of floral Evolution in the Eudicot Order Fabales

Cladistics Cladistics 1 (2012) 1–29 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2012.00392.x Combined phylogenetic analyses reveal interfamilial relationships and patterns of floral evolution in the eudicot order Fabales M. Ange´ lica Belloa,b,c,*, Paula J. Rudallb and Julie A. Hawkinsa aSchool of Biological Sciences, Lyle Tower, the University of Reading, Reading, Berkshire RG6 6BX, UK; bJodrell Laboratory, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3DS, UK; cReal Jardı´n Bota´nico-CSIC, Plaza de Murillo 2, CP 28014 Madrid, Spain Accepted 5 January 2012 Abstract Relationships between the four families placed in the angiosperm order Fabales (Leguminosae, Polygalaceae, Quillajaceae, Surianaceae) were hitherto poorly resolved. We combine published molecular data for the chloroplast regions matK and rbcL with 66 morphological characters surveyed for 73 ingroup and two outgroup species, and use Parsimony and Bayesian approaches to explore matrices with different missing data. All combined analyses using Parsimony recovered the topology Polygalaceae (Leguminosae (Quillajaceae + Surianaceae)). Bayesian analyses with matched morphological and molecular sampling recover the same topology, but analyses based on other data recover a different Bayesian topology: ((Polygalaceae + Leguminosae) (Quillajaceae + Surianaceae)). We explore the evolution of floral characters in the context of the more consistent topology: Polygalaceae (Leguminosae (Quillajaceae + Surianaceae)). This reveals synapomorphies for (Leguminosae (Quillajaceae + Suri- anaceae)) as the presence of free filaments and marginal ⁄ ventral placentation, for (Quillajaceae + Surianaceae) as pentamery and apocarpy, and for Leguminosae the presence of an abaxial median sepal and unicarpellate gynoecium. An octamerous androecium is synapomorphic for Polygalaceae. The development of papilionate flowers, and the evolutionary context in which these phenotypes appeared in Leguminosae and Polygalaceae, shows that the morphologies are convergent rather than synapomorphic within Fabales. -

(Poaceae: Panicoideae) in Thailand

Systematics of Arundinelleae and Andropogoneae, subtribes Chionachninae, Dimeriinae and Germainiinae (Poaceae: Panicoideae) in Thailand Thesis submitted to the University of Dublin, Trinity College for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) by Atchara Teerawatananon 2009 Research conducted under the supervision of Dr. Trevor R. Hodkinson School of Natural Sciences Department of Botany Trinity College University of Dublin, Ireland I Declaration I hereby declare that the contents of this thesis are entirely my own work (except where otherwise stated) and that it has not been previously submitted as an exercise for a degree to this or any other university. I agree that library of the University of Dublin, Trinity College may lend or copy this thesis subject to the source being acknowledged. _______________________ Atchara Teerawatananon II Abstract This thesis has provided a comprehensive taxonomic account of tribe Arundinelleae, and subtribes Chionachninae, Dimeriinae and Germainiinae of the tribe Andropogoneae in Thailand. Complete floristic treatments of these taxa have been completed for the Flora of Thailand project. Keys to genera and species, species descriptions, synonyms, typifications, illustrations, distribution maps and lists of specimens examined, are also presented. Fourteen species and three genera of tribe Arundinelleae, three species and two genera of subtribe Chionachninae, seven species of subtribe Dimeriinae, and twelve species and two genera of Germainiinae, were recorded in Thailand, of which Garnotia ciliata and Jansenella griffithiana were recorded for the first time for Thailand. Three endemic grasses, Arundinella kerrii, A. kokutensis and Dimeria kerrii were described as new species to science. Phylogenetic relationships among major subfamilies in Poaceae and among major tribes within Panicoideae were evaluated using parsimony analysis of plastid DNA regions, trnL-F and atpB- rbcL, and a nuclear ribosomal DNA region, ITS. -

Synoptic Overview of Exotic Acacia, Senegalia and Vachellia (Caesalpinioideae, Mimosoid Clade, Fabaceae) in Egypt

plants Article Synoptic Overview of Exotic Acacia, Senegalia and Vachellia (Caesalpinioideae, Mimosoid Clade, Fabaceae) in Egypt Rania A. Hassan * and Rim S. Hamdy Botany and Microbiology Department, Faculty of Science, Cairo University, Giza 12613, Egypt; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: For the first time, an updated checklist of Acacia, Senegalia and Vachellia species in Egypt is provided, focusing on the exotic species. Taking into consideration the retypification of genus Acacia ratified at the Melbourne International Botanical Congress (IBC, 2011), a process of reclassification has taken place worldwide in recent years. The review of Acacia and its segregates in Egypt became necessary in light of the available information cited in classical works during the last century. In Egypt, various taxa formerly placed in Acacia s.l., have been transferred to Acacia s.s., Acaciella, Senegalia, Parasenegalia and Vachellia. The present study is a contribution towards clarifying the nomenclatural status of all recorded species of Acacia and its segregate genera. This study recorded 144 taxa (125 species and 19 infraspecific taxa). Only 14 taxa (four species and 10 infraspecific taxa) are indigenous to Egypt (included now under Senegalia and Vachellia). The other 130 taxa had been introduced to Egypt during the last century. Out of the 130 taxa, 79 taxa have been recorded in literature. The focus of this study is the remaining 51 exotic taxa that have been traced as living species in Egyptian gardens or as herbarium specimens in Egyptian herbaria. The studied exotic taxa are accommodated under Acacia s.s. (24 taxa), Senegalia (14 taxa) and Vachellia (13 taxa). -

Supporting Information

Supporting Information Christin et al. 10.1073/pnas.1216777110 SI Materials and Methods blades were then embedded in resin (JB-4; Polysciences), Phylogenetic Inference. A previously published 545-taxa dataset of following the manufacturer’s instructions. Five-micrometer the grasses based on the plastid markers rbcL, ndhF,andtrnK-matK thick cross-sections of the embedded leaf fragments were cut (1) was expanded and used for phylogenetic inference. For species with a microtome and stained with saturated cresyl violet sampled for anatomical cross-sections but not included in the acetate (CVA). Some samples were fixed in formalin-pro- published dataset, the markers ndhF and/or trnK-matK were either pionic acid-alcohol (FPA), embedded in paraffin, sectioned at retrieved from GenBank when available or were newly sequenced 10 μm, and stained with a safranin O-orange G series (11) as from extracted genomic DNA with the method and primers de- described in (12). All slides were made permanent and are scribed previously (1, 2). These new sequences were aligned to the available on request. dataset, excluding the regions that were too variable as described previously (1). The final dataset totaled 604 taxa and was used for Anatomical Measurements. All C3 grasses possess a double BS, with “ phylogenetic inference as implemented in the software Bayesian the outer layer derived from ground meristem to form a paren- ” Evolutionary Analysis by Sampling Trees (BEAST) (3). chyma sheath, and the internal layer derived from the vascular “ ” The phylogenetic tree was inferred under a general time-re- procambium to form a mestome sheath (13). Many C4 grasses versible substitution model with a gamma-shape parameter and also possess these two BS layers, with one of them specialized in “ ” a proportion of invariants (GTR+G+I).