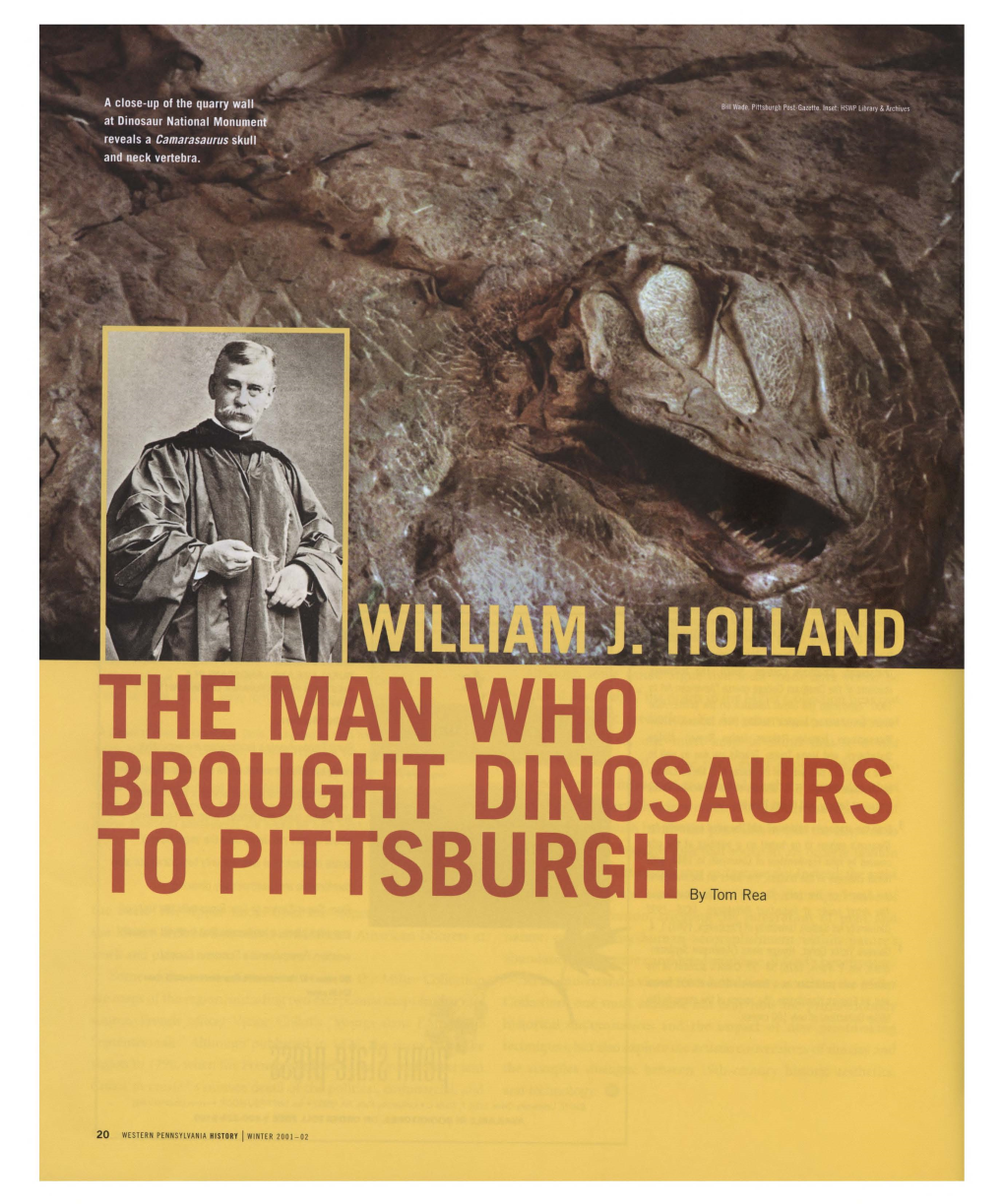

Brought Dinosaurs to Pittsburgh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By HENRY FAIRFIELD OSBORN and CHARL

VoL. 6, 1920 PALAEONTOLOGY: OSBORN AND MOOK IS RECONSTRUCTION OF THE SKELETON OF THE SAUROPOD DINOSAUR CAMARASA URUS COPE (MOROSA URUS MARSH) By HENRY FAIRFIELD OSBORN AND CHARLES CRAIG MOOK AMERICAN MusEUM or NATURAL HISTORY, NEW YORK CITY Read before the Academy, November 11, 1919 The principles of modern research in vertebrate palaeontology are illustrated in the fifteen years' work resulting in the restoration of the massive sauropod dinosaur known as Camarasaurus, the "chambered saurian.." The animal was found near Canyon City, Colorado, in March, 1877. The first bones were described by Cope, August 23, 1877. The first at- tempted restoration was by Ryder, December 21, 1877. The bones analyzed by this research were found probably to belong to six individuals of Camarasaurus mingled with the remains of some carnivorous dinosaurs, all from the summit of the Morrison formation, now regarded as of Jurassic- Cretaceous age. In these two quarries Cope named nine new genera and fourteen new species of dinosaurs, none of which have found their way into. palaeontologic literature, excepting Camarasaurus. Out of these twenty-three names we unravel three genera, namely: One species of Camarasaurus, identical with Morosaurus Marsh. One species of Amphicaclias, close to Diplodocus Marsh. One species of Epanterias, close to Allosaurus Marsh. The working out of the Camarasaurus skeleton results in both the artica ulated restoration and the restoration of the musculature. The following are the principal characters: The neck is very flexible; anterior vertebrae of the back also freely movable; the division between the latter and the relatively rigid posterior dorsals is sharp. -

Library Collections and Services

Library Collections and Services The University of Pittsburgh libraries and collections The University of Pittsburgh is a member of the provide an abundant amount of information and services to the Association of Research Libraries. Through membership in University’s students, faculty, staff, and researchers. In fiscal several Pennsylvania consortia of libraries, which include year 2001, the University's 29 libraries and collections have PALCI, PALINET, and the Oakland Library Consortium, surpassed 4.4 million volumes. Additionally, the collections cooperative borrowing arrangements have been developed with include more than 4.3 million pieces of microforms, 32,500 print other Pennsylvania institutions. Locations of University libraries subscriptions, and 5,400 electronic journals. and collections are as follows: The University Library System (ULS) includes the following libraries and collections: Hillman (main), African American, Buhl University Library System (social work), East Asian, Special Collections, Government Documents, Allegheny Observatory, Archives Service Center, Hillman Library ......... Schenley Drive at Forbes Avenue Center for American Music, Chemistry, Computer Science, Hillman Library (main) .................... All floors Darlington Memorial (American history), Engineering (Bevier African American Library ................. First Floor Library), Frick Fine Arts, Information Sciences, Katz Graduate Buhl Library (social work) ................. First Floor School of Business, Langley (biological sciences, East Asian Library -

John Bell Hatcher.1 Bokn October 11, 1861

568 Obituary—J. B. Hatcher. " Description of a New Genus [Stelidioseris] of Madreporaria from the Sutton Stone of South "Wales": Quart. Journ. Geol. Soc, vol. xlix (1893), pp. 574-578, and pi. xx. " Observations on some British Cretaceous Madreporaria, with the Description of two New Species " : GEOL. MAG., 1899, pp. 298-307. " Description of a Species of Heteraslraa lrom the Lower Rhsetic of Gloucester- shire" : Quart. Journ. Geol. Soc, lix (1903), pp. 403-407, and figs, in text. JOHN BELL HATCHER.1 BOKN OCTOBER 11, 1861. DIED JULY 3, 1904. THE Editor of the Annals of the Carnegie Museum, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, U.S., records with deep regret the death, on July 3rd, 1904, of his trusted associate, Mr. John Bell Hatcher. Mr. Hatcher was born at Cooperstown, Brown County, Illinois, on October 11th, 1861. He was the son of John and Margaret C. Hatcher. The family is Virginian in extraction. In his boyhood his parents removed to Greene County, Iowa, where his father, who with his mother survive him, engaged in agricultural pursuits near the town of Cooper. He received his early education from his father, who in the winter months combined the work of teaching in the schools with labour upon his farm. He also attended the public schools of the neighbourhood. In 1880 he entered Grinnell College, Iowa, where he remained for a short time, and then went to Yale College, where he took the degree of Bachelor in Philosophy, in July, 1884. While a student at Yale his natural fondness for scientific pursuits asserted itself strongly, and he attracted the attention of the late Professor Othniel C. -

Brains and Intelligence

BRAINS AND INTELLIGENCE The EQ or Encephalization Quotient is a simple way of measuring an animal's intelligence. EQ is the ratio of the brain weight of the animal to the brain weight of a "typical" animal of the same body weight. Assuming that smarter animals have larger brains to body ratios than less intelligent ones, this helps determine the relative intelligence of extinct animals. In general, warm-blooded animals (like mammals) have a higher EQ than cold-blooded ones (like reptiles and fish). Birds and mammals have brains that are about 10 times bigger than those of bony fish, amphibians, and reptiles of the same body size. The Least Intelligent Dinosaurs: The primitive dinosaurs belonging to the group sauropodomorpha (which included Massospondylus, Riojasaurus, and others) were among the least intelligent of the dinosaurs, with an EQ of about 0.05 (Hopson, 1980). Smartest Dinosaurs: The Troodontids (like Troödon) were probably the smartest dinosaurs, followed by the dromaeosaurid dinosaurs (the "raptors," which included Dromeosaurus, Velociraptor, Deinonychus, and others) had the highest EQ among the dinosaurs, about 5.8 (Hopson, 1980). The Encephalization Quotient was developed by the psychologist Harry J. Jerison in the 1970's. J. A. Hopson (a paleontologist from the University of Chicago) did further development of the EQ concept using brain casts of many dinosaurs. Hopson found that theropods (especially Troodontids) had higher EQ's than plant-eating dinosaurs. The lowest EQ's belonged to sauropods, ankylosaurs, and stegosaurids. A SECOND BRAIN? It used to be thought that the large sauropods (like Brachiosaurus and Apatosaurus) and the ornithischian Stegosaurus had a second brain. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 Fossil Excavation, Museums, and Wyoming: American Paleontology, 1870-1915 Marlena Briane Cameron Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES FOSSIL EXCAVATION, MUSEUMS, AND WYOMING: AMERICAN PALEONTOLOGY, 1870-1915 By MARLENA BRIANE CAMERON A Thesis submitted to the Program in the History and Philosophy of Science in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2017 Marlena Cameron defended this thesis on July 17, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: Ronald E. Doel Professor Directing Thesis Michael Ruse Committee Member Kristina Buhrman Committee Member Sandra Varry Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ iv Abstract ............................................................................................................................................v 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................1 2. THE BONE WARS ....................................................................................................................9 -

American Museum 1869-1927

BUILDING THE AMERICAN MUSEUM 1869-1927 "4jr tbt purpose of e%tablifing anb manataining in %aib citp a Eu%eum anb iLbrarp of gIatural biotorr; of encouraging anb bebeloping tde otubp of A"aturalOcience; of abbancting the general kno)alebge of kinbreb %ub;ectt, anb to tiat enb of furniobing popular inotruction." FIFTY1NINTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE TRUSTEES FOR THE YEAR 1927 - THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY IHE CITY OF NEW YORK Issued May 1, 1928 BUILDING THE AMERICAN MUSEUM 1869-1927 PRESIDENT HENRY FAIRFIELD OSBORN And David said to Solomon his son, "Be strong and of good courage, and do it; fear not, nor be dismayed: for the Lord God, even my God, uill be with thee; he will not fail thee, nor forsake thee, until thou hast finished all the work for the service of the house of the Lord."-Chronicles I, XXVIII. In 1869, Albert S. Bickmore, a young naturalist of the State of Maine, projected this great Museum. First advised by Sir Richard Owen, Director of the British Museum, the plans for the building grew by the year 1875 into the titanic dimensions plotted by Frederick Law Olmsted, designer of Central Park. The approaching sixtieth anniversary of our foundation, on April 6, 1929, will witness the construction of fourteen out of the twenty-one building sections planned by Professor Albert S. Bickmore and Mr. Frederick L-aw Olmsted. With strength and courage, the seventieth anniversary, April 6, 1939, will witness the completion of the Museum building according to the plan set forth in this Report. -

Residence Quick Reference

UPMC Hillman Cancer Center Academy Residential Quick Reference This is a quick reference sheet about the relevant information and policies that any students staying in the dorm should know. Some minor specifics may change year to year, such as the dorm or exact curfew hours, but overall policies are consistent. Location: Forbes Hall - https://pc.pitt.edu/housing/halls/forbes.php 3525 Forbes Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Students, Doris Duke, Interns, and Resident advisors will be staying in Forbes Hall. The dorm is located on the west side of the university campus. University Policies: Students in the dorms will be expected to follow all University of Pittsburgh Housing policies, in addition to the policies of the Hillman Academy. A detailed look at the policies can be found here - https://www.pc.pitt.edu/housing/policies.php You can also contact Panther Central for any questions related to Pitt or the dorms. (info below) The most important ones to note are the Guest, Technology, and Substance policies. Transportation: Transportation to and from your lab, keynote addresses, and events will be provided. We hire a private shuttle to take students to and from these required events. Anyone staying in the dorm will have access to the Pitt shuttle but not to the Port Authority (the public transit system in Pittsburgh). Getting transportation aside from these times is up to the resident. Students whose labs are located in the Oakland area are allowed to walk to their lab as they are within a few blocks. Resident Advisors: The dorm will have (usually) 3-5 Resident Advisors who will stay in the dorm with the students. -

A Revision of the Ceratopsia Or Horned Dinosaurs

MEMOIRS OF THE PEABODY MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY VOLUME III, 1 A.R1 A REVISION orf tneth< CERATOPSIA OR HORNED DINOSAURS BY RICHARD SWANN LULL STERLING PROFESSOR OF PALEONTOLOGY AND DIRECTOR OF PEABODY MUSEUM, YALE UNIVERSITY LVXET NEW HAVEN, CONN. *933 MEMOIRS OF THE PEABODY MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY YALE UNIVERSITY Volume I. Odontornithes: A Monograph on the Extinct Toothed Birds of North America. By Othniel Charles Marsh. Pp. i-ix, 1-201, pis. 1-34, text figs. 1-40. 1880. To be obtained from the Peabody Museum. Price $3. Volume II. Part 1. Brachiospongidae : A Memoir on a Group of Silurian Sponges. By Charles Emerson Beecher. Pp. 1-28, pis. 1-6, text figs. 1-4. 1889. To be obtained from the Peabody Museum. Price $1. Volume III. Part 1. American Mesozoic Mammalia. By George Gaylord Simp- son. Pp. i-xvi, 1-171, pis. 1-32, text figs. 1-62. 1929. To be obtained from the Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn. Price $5. Part 2. A Remarkable Ground Sloth. By Richard Swann Lull. Pp. i-x, 1-20, pis. 1-9, text figs. 1-3. 1929. To be obtained from the Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn. Price $1. Part 3. A Revision of the Ceratopsia or Horned Dinosaurs. By Richard Swann Lull. Pp. i-xii, 1-175, pis. I-XVII, text figs. 1-42. 1933. To be obtained from the Peabody Museum. Price $5 (bound in cloth), $4 (bound in paper). Part 4. The Merycoidodontidae, an Extinct Group of Ruminant Mammals. By Malcolm Rutherford Thorpe. In preparation. -

The Fighting Pair

THE FIGHTING PAIR ALLOSAURUS VS STEGOSAURUS — Allosaurus “jimmadsoni” and Hesperosaurus (Stegosaurus) mjosi Upper Jurassic Period, Kimmeridgian Stage, 155 million years old Morrison Formation Dana Quarry, Ten Sleep, Washakie County, Wyoming, USA. THE ALLOSAURUS The Official State Fossil of Utah, the Allosaurus was a large theropod carnosaur of the “bird-hipped” Saurischia order that flourished primarily in North America during the Upper Jurassic Period, 155-145 million years In the spring of 2007, at the newly-investigated Dana Quarry in the Morrison Formation of Wyoming, the team from ago. Long recognized in popular culture, it bears the distinction of being Dinosauria International LLC made an exciting discovery: the beautifully preserved femur of the giant carnivorous one of the first dinosaurs to be depicted on the silver screen, the apex Allosaur. As they kept digging, their excitement grew greater; next came toe bones, leg bones, ribs, vertebrae and predator of the 1912 novel and 1925 cinema adaptation of Conan Doyle’s finally a skull: complete, undistorted and, remarkably, with full dentition. It was an incredible find; one of the most The Lost World. classic dinosaurs, virtually complete, articulated and in beautiful condition. But that was not all. When the team got The Allosaurus possessed a large head on a short neck, a broad rib-cage the field jackets back to the preparation lab, they discovered another leg bone beneath the Allosaurus skull… There creating a barrel chest, small three-fingered forelimbs, large powerful hind limbs with hoof-like feet, and a long heavy tail to act as a counter-balance. was another dinosaur in the 150 million year-old rock. -

HPCC Committees

February 2016 Community Council Newsletter IN THIS ISSUE: A Letter from Highland Park 1 the President January Meeting 2 Minutes No Limits for Women - 3 Pittsburgh for CEDAW Pennsylvania to Eliminate Vehicle 4 Registration Stickers in 2017 Restoring “Dippy” the 5 Dinosaur The Maltese Falcon 75th 6 Anniversary Event The Cub Scouts Make 6 a Difference Joseph Tambellini Rated One of 6 the 100 Best Restaurants in America Around 7 St. Andrew’s In case there is any confusion, the OLEA is not open yet. DPW has made great progress this winter and while the fencing may look complete, they are still waiting on several panels to arrive so they can complete construction. There is some temporary chain link fence in place to keep the area closed, but it might be 6-8 weeks before the additional fencing arrives. There are also gaps under some of the fence that still need to be Walking the Neighborhood addressed as smaller dogs may be able to escape through them. With the house tour planned for May 7th, the Saturday of Mother’s Day weekend, the HPCC To keep people from using the OLEA before it is House Tour Committee has been meeting every made safe for both you and your pets, DPW has Sunday morning to plan the event and spend temporarily padlocked the gate. time walking around the neighborhood looking at houses for the tour. During our walks, we have In the short time that people were using it met many wonderful neighbors and continue to before the gates were locked, it became evident be amazed at the friendliness and generosity of that the high traffic areas need some sort of our community. -

In South Kensington, C. 1850-1900

JEWELS OF THE NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM: GENDERED AESTHETICS IN SOUTH KENSINGTON, C. 1850-1900 PANDORA KATHLEEN CRUISE SYPEREK PH.D. HISTORY OF ART UCL 2 I, PANDORA KATHLEEN CRUISE SYPEREK confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. ______________________________________________ 3 ABSTRACT Several collections of brilliant objects were put on display following the opening of the British Museum (Natural History) in South Kensington in 1881. These objects resemble jewels both in their exquisite lustre and in their hybrid status between nature and culture, science and art. This thesis asks how these jewel-like hybrids – including shiny preserved beetles, iridescent taxidermised hummingbirds, translucent glass jellyfish as well as crystals and minerals themselves – functioned outside of normative gender expectations of Victorian museums and scientific culture. Such displays’ dazzling spectacles refract the linear expectations of earlier natural history taxonomies and confound the narrative of evolutionary habitat dioramas. As such, they challenge the hierarchies underlying both orders and their implications for gender, race and class. Objects on display are compared with relevant cultural phenomena including museum architecture, natural history illustration, literature, commercial display, decorative art and dress, and evaluated in light of issues such as transgressive animal sexualities, the performativity of objects, technologies of visualisation and contemporary aesthetic and evolutionary theory. Feminist theory in the history of science and new materialist philosophy by Donna Haraway, Elizabeth Grosz, Karen Barad and Rosi Braidotti inform analysis into how objects on display complicate nature/culture binaries in the museum of natural history. -

Letters to Andrew Carnegie ∂

Letters to Andrew Carnegie ∂ A CENTURY OF PURPOSE, PROGRESS, AND HOPE Letters to Andrew Carnegie ∂ A CENTURY OF PURPOSE, PROGRESS, AND HOPE Copyright © 2019 Carnegie Corporation of New York 437 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10022 Letters to Andrew Carnegie ∂ A CENTURY OF PURPOSE, PROGRESS, AND HOPE CARNEGIE CORPORATION OF NEW YORK 2019 CONTENTS vii Preface 1 Introduction 7 Carnegie Hall 1891 13 Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh 1895 19 Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh 1895 27 Carnegie Mellon University 1900 35 Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland 1901 41 Carnegie Institution for Science 1902 49 Carnegie Foundation 1903 | Peace Palace 1913 57 Carnegie Hero Fund Commission 1904 61 Carnegie Dunfermline Trust 1903 | Carnegie Hero Fund Trust 1908 67 Carnegie Rescuers Foundation (Switzerland) 1911 73 Carnegiestiftelsen 1911 77 Fondazione Carnegie per gli Atti di Eroismo 1911 81 Stichting Carnegie Heldenfonds 1911 85 Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching 1905 93 Carnegie Endowment for International Peace 1910 99 Carnegie Corporation of New York 1911 109 Carnegie UK Trust 1913 117 Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs 1914 125 TIAA 1918 131 Carnegie Family 135 Acknowledgments PREFACE In 1935, Carnegie Corporation of New York published the Andrew Carnegie Centenary, a compilation of speeches given by the leaders of Carnegie institutions, family, and close associates on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Andrew Carnegie’s birth. Among the many notable contributors in that first volume were Mrs. Louise Carnegie; Nicholas Murray Butler, president of both the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and Columbia University; and Walter Damrosch, the conductor of the New York Symphony Orchestra whose vision inspired the building of Carnegie Hall.