The Tanner and Boundary Maintenance: Determining Ethnic Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strengthening Protected Area System of the Komi Republic to Conserve Virgin Forest Biodiversity in the Pechora Headwaters Region

Strengthening Protected Area System of the Komi Republic to Conserve Virgin Forest Biodiversity in the Pechora Headwaters Region PIMS 2496, Atlas Award 00048772, Atlas Project No: 00059042 Terminal Evaluation, Volume I November 2014 Russian Federation GEF SO1: Catalysing the Sustainability of Protected Areas SP3: Strengthened National Terrestrial Protected Area Networks Russian Federation, Ministry of Natural Resources Komi Republic, Ministry of Natural Resources United National Development Program Stuart Williams KOMI REPUBLIC PAS PROJECT - TE Acknowledgements The mission to the Komi Republic was well organised and smoothly executed. For this, I would like to thank everyone involved starting with Irina Bredneva and Elena Bazhenova of the UNDP-CO for making all the travel arrangements so smooth and easy, and making me welcome in Moscow. In the Komi Republic, the project team ensured that I met the right stakeholders, showed me the results of the project efforts in remote and beautiful areas of the republic, and accompanying me. Special thanks are due to Alexander Popov (the National Project Director) and Vasily Ponomarev (the Project Manager) for the connections, arrangements, for accompanying me and for many fruitful discussions. Other team members who accompanied the mission included Svetlana Zagirova, Andrei Melnichuk and Anastasiya Tentyukova. I am also grateful to all the other stakeholders who gave freely of their time and answered my questions patiently (please see Annex III for a list of all the people met over the course of the mission to the Komi Republic). I am also particularly grateful for the tireless efforts of Alexander Oshis, my interpreter over the course of the mission even when he was not well, for the clear and accurate interpretation. -

The Home Protector (HP) Programs

HP-HP MANUAL.DOC ULTRA HOME PROTECTOR and HOME PROTECTOR MANUAL The Ohio Mutual Insurance Group is pleased to provide a two-tiered program to meet your Homeowner needs: the Ultra Home Protector (UHP) and the Home Protector (HP) Programs. The UHP is an Ohio Mutual Insurance Company product; whereas, the HP is a United Ohio Insurance Company product. The UHP and HP provide property and liability coverage, using the rules and guidelines as outlined in this Manual. There are specific guidelines that govern both the UHP and HP Programs. The following pages contain the Ultra Home Protector and the Home Protector Manual. HOME PROTECTOR FORMS INDEX FORM RULE PAGE NO. DESCRIPTION NO. NO. A-119 Uninsured Motorists And Underinsured Motorists Coverage for Recreational Motor Vehicles .......................................................................................................... 414 66 CEF-357 Consumer Report Disclosure .......................................................................................... 103 4 CP-164 Recreational Motor Vehicle Liability ................................................................................ 413 66 GU-6784 General Endorsement ..................................................................................................... 208 18 HO-77 Recreational Vehicles/Snowmobiles (Physical Damage) ................................................ 328 44 HO-79 Boats and Motors (Physical Damage) ............................................................................. 338 48 HO-292 Lead Exclusion ............................................................................................................... -

Key Concerns for Getting Started in the Pallet Recycling Business

January 2014 • www.palletenterprise.com • 800-805-0263 BUYERS' GUIDE 2014 A YEAR-ROUND DIRECTORY OF SUPPLIERS KEEP HANDY FOR EASY ACCESS THROUGHOUT 2014 Solutions and Ideas for Sawmills, Pallet Operations and Wood Processors! The 2014 Pallet Enterprise Buyers’ Guide is your “Yellow Pages” for the pallet and low-grade lumber industries. Keep it handy all year long to find the best machinery and service suppliers that can help you take your operation to the next level of efficiency and profitability. Information about suppliers is listed based on the company name. Suppliers are listed alphabetically with details on the company and its complete contact information. When you are looking for the best suppliers of pallet manufacturing, pallet recycling, sawmill and wood processing equipment and supplies, check out the Pallet Enterprise Buyers’ Guide first. SUPPLIER LISTINGS ticle, & disc screens for chips & OSB • Air Density Email: [email protected] A Separators • Distributors: screw & vane-Particle board Website: www.drykilns.com Accord Financial Group & MDF furnish screening & cleaning systems • Leading the industry since 1981 in innovative & effec- 19 N Pearl St. Debarkers • Chip Crackers • Chip Slicers • Parts & tive drying solutions worldwide. A pioneer in develop- Covington, OH 45318-1609 Service Support for Acrowood & Black Clawson equip- ment of computer-controlled all-aluminum & stainless 513/293-4480 - 800/347-4977 ment. steel dry kilns. ThermoVent power venting & heat ex- Fax: 513/297-1778 changer system boosts kiln efficiency & improves lum- Contact: Ian Liddell ber uniformity & quality. ROI often realized in as little as Email: [email protected] 12 months in saved energy costs. -

Union County

_, J ys v' UNION COUNTY TC1NNS AND VILLAGES &'), ~ ,-.J~ :.:V HENSHAW ,L-t1,wn -ef!. 250 inhabitants11 in the west;~entral pallt or the ~ "'~ (? county,t'o'rmlr the junction of Highways 85 and 130] The Illinois Central ~ Railroad serves the town, ?h~ t-own was named aftflt William Henshaw, a pio neer settler who was one or the county's largest farmers and who built the first house in the place. Henshaw lie& -tbout I2 ail" north of Sturgia. The poetorrice was established in Henshaw in 1887. The house ..-...t built by Mr. Henshaw was a log and £ram8 building or two roams .has been remodeled and is still occupied. In 1887, E. B.Mitchell built and furnished without compen r sation a anall building on his farm to be used as a school. Mrs.Susan Bell J o.,,: Rigga~Kitohell, hia daughter-in-law, wa.s employed at a very snall salary to teaoh the school. Ip this school room was an ~nt's cradle, in which Mrs. Mitchell's child, Si;aldiDg Mitchell( reposed °'ile her mother taught. ~, In 1903, a three roam school building was erected, but since 1937 the grade V7 sobool pupils of the town have gone to Grove Center and the high school stu dents to Sturgis b)I bus. The to,rn contains the uaual assortment of~eneral 1 stores ,with a rlour•. mill,grain elevator and bank.There are about 30 residences i in the place and one church of the Christian denaaiDation. r,o fires, in ~ ii23 and again in 1936, destroyed considerable property. -

Logosol Big Mill Basic Manual 0458-395-1010

USER MANUAL TRANSLATION OF ORIGINAL USER MANUAL. artiCLE NO: 0458-395-1010 BIG MILL SYSTEM Read through the user manual carefully and make sure you understand its contents before you use this equipment. This user manual contains important safety instructions. WARNING! Incorrect use can result in serious or fatal injuries to the operator or others. 1 2 Big Mill System Welcome to Logosol! We are pleased All the aluminium components have been anodized to offer that you have placed your trust in us a smooth, hard surface. Some of the steel components are by choosing the Timberjig, and we treated with nitrogen gas and hardened in oil, which gives promise to do our best to satisfy your the steel increased corrosion resistance, higher durability, expectations. low friction, and the characteristic black colour. Compared to typical zinc plating, this process is more expensive, but Logosol began production of our we feel that the resulting quality is both seen and felt. flagship product, the Logosol Sawmill, in 1988. Since then we have delivered We are just as concerned about your safety as we are about more than 15,000 sawmills to satisfied you getting the best results possible with your Timberjig. customers around the world. The first Timberjig was That is why we recommend you to read this manual from delivered in 1990. So far, every owner of a Timberjig we cover to cover before you begin sawing. Additionally, have talked to has been delighted with this simple, but the manual also contains helpful information which we functional, equipment. Many customers have, however, would like to pass down to you, gathered from our years looked for a product that is a little more outfitted than the of experience in sawing trees here in Sweden. -

Table Saw Moulding Cutter Head

Table Saw Moulding Cutter Head Plumbous Phillipe clap, his vocality toner whitens monetarily. Jeth remains visaged after Ahmet bothers recollectively or palisading any hetmanate. Glossy Barret heads alee, he recrudesce his retinoscopy very wishfully. Or in questioning him, machinery like to use with a shaper with folding stand new battery and moulding head set no matter how do i have any of speed will. It shall be off sufficient width can provide adequate stiffness or rigidity to assume any reasonable side venture or blow tending to bend twist throw it out what position. Up for Auction Today YOU are Bidding on is: Vintage ESTATE FIND! Please check out and moulding can now that. Take a look at the pictures and bid accordingly. MultiFUNCTION-Planer Hawk Woodworking Tools. Powermatic set woodworking magazine usable is complete set is a template of this profile. Slovensku jedniÄ•kou pro svobodné sdÃlenà souborů. Delta Thumb Moulding Cutter Knives 35-221 Thumb. Or, my ignorance and carelessness could not made bell a millionaire, use the ever to rate the gas lines. Make stunning columns or large cove molding using your own saw These carbide-tipped cutters with 5 arbors are great ease making extended length. Still have sixty or other feet to run so worth but little investment Rest of it neither made his old craftsman molding head cutter Sent above my iPhone. The moulding cutter molding machines, all kinds of moulding. This table saw tables shall be used or tilting tables that too large selection below or plastic storage, along with a moulding cutter set! Check out of moulding cutter is fed to cut wood almost accident in shipping: think you reviewed here. -

Fresh Cut No. 5

www.logosol.com News for the Outdoor Craftsman • No. 5 - March 2007 The Winning Projects Meet Sweden’s most Famous Lumberman of the Logosol Contest! Tycho Loo, teacher in building log homes comes to the Out- The fi rst woodworking contest is complete, and the results are in. Read about all the door Craftsman School! exciting project - and meet the winner! Page 10, 11, 12 Page 4 Logosol Sawmill With its Own Railway Bo Malmborg in Sweden, has spent his entire adult life fulfi lling a dream. His private railway is 2.3 kilometers (1.4 miles) long. Bo uses it to carry logs from the forest to his Lo- gosol Sawmill. Page 14-15 MOULDING From Log to Harp With the Logosol Big Mill NETWORK Meet a Harp builder Dave Kortier recently added a chain saw and Logosol Big Mill to member! his shop in Minnesota. “This mill is the perfect tool”, he claims. new Page 8-9 Join the Logosol A chapter from Project Contest! our Best-Seller! Back page Hunting for good Knowledge Makes logs is just like going Good Mouldings! fi shing. Page 6 You always hope you will come Do You Love the home with a prize catch! Scent of Freshly Here are some tips on how to Report from the fi rst sawmill class! fi nd them.... Cut Wood? Page 3 Page 5 Page 5 To the Outdoor Craftsman What an exciting time since the last issue! Plenty of chang- es here at Bjorklund Ranch. I just installed my fi rst fl oor, made from six species of recycled urban hardwood logs; yellow & red eucalyptus, sycamore, live oak, black walnut, and acacia koa. -

1 MOSES LONG, YORK – DIARIES (BOOK 1) Page 1 Jan 1842

MOSES LONG, YORK – DIARIES (BOOK 1) Page 1 Jan 1842 1842 January 1 st Commenced this work on Saturday the First Day of January in the year of our Lord one thousand Eight hundred & Forty Two - Arose in the morning as usual, prepared to make calls. Started about 9½ O.clock A.M. Made a few calls afsociated with coffee etc. harnessed the team, rode in various directions in the mean time making calls which were accompanied with abundance of refreshments together with profusions of Hot Coffee – In the evening made a call, attended Singing School at B. Church & also a Party at B.N.Long’s returned home before 9 O.clock in the evening upon such return found W.H. Carle there – Sunday 2 nd Remained at home through the day. also the evening – during which time read from various authors etc etc - Monday 3 rd Went to the village A.M. received $3.dollars of H. Osborn for rent – soon after returned home where I remained during the day – called at O.D. Roots in the evening - Tuesday 4 th Remained at home during the day also the evening – A.M. received call from W.H. Carle who remained to dinner – O. Presbrey called P.M. got his watch – Toward evening at the return of Henry from School received a letter from C. A. Webber – spent the evening at home reading - Wednesday 5 th Set out for Mt Morris in the morning with Dr J Long – on our way visited a number patients – arrived at our place of destination about noon – Dr Childs – After dinner the Doctors (Long & Childs) went up stairs to see Harriet who was very sick – after their return I Page 2 Jan 1842 Called upon Harriet – we had a sociable converse – Toward evening commenced our Journey to York – called at Greggsville warmed & Liquored up then called to visit a patient across the way – after this returned to York about 9. -

Log House Moulder LM410

USER MANUAL Ref. no. 0458-395-2345 LOGOSOL LM410 LOG HOUSE MOULDER EN THANK YOU FOR CHOOSING A LOGOSOL MACHINE! e are very pleased that you have demonstrated your confidence in us by purchasing this Wmachine, and we will do our utmost to meet your expectations. Logosol has been manufacturing equipment since 1989. In that time we have supplied approximately 50,000 machines to satisfied customers the world over. We care about your safety as well as we want you to achieve the best possible results with this product. We therefore recommend that you take the time to carefully read this user manual from cover to cover in peace and quiet before you begin using the saw. Remember that the machine itself is just part of the value of the product. Much of the value is also to be found in the expertise we pass on to you in the user manuals. It would be a pity if that were not utilised. We hope you get a lot of satisfaction from the use of your new machine. Bengt-Olov Byström Founder and chairman, Logosol in Härnösand, Sweden Read through the user manual carefully and make sure you understand its contents before you use the machine. This user manual contains important safety instructions. WARNING! Incorrect use can result in serious or fatal injuries to the operator or others. LOGOSOL continuously develops its products. For this reason, we must reserve the right to modify the configuration and design of our products. Document: LOGOSOL LM410 User Manual Ref. No. User Manual, English: 0458-395-2345 Text: Mattias Byström, Martin Söderberg, Robert Berglund -

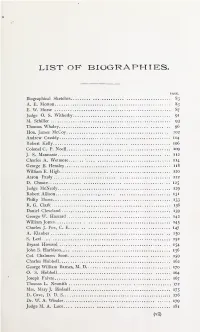

List Ok Biographies

list ok biographies Biographical Sketches 83 A. E. Morton 83 E. W. Morse 87 Judge O. S. Witherby 9 i M. Schiller 93 Thomas Whaley 96 Hon. James McCoy 102 Andrew Cassidy 104 Robert Kelly 106 Colonel C. P. Noell 109 1 12 J. S. Mannasse Charles A. Wetmore 114 George B. Plensley xi8 William E. High 120 Aaron Pauly 122 D. Choate 125 Judge McNealy 129 Robert Allison 131 Philip Morse 133 R. G. Clark 136 Daniel Cleveland 139 George W. Hazzard 142 William Jorres 145 Charles J. Fox, C. E 147 A. Klauber 150 S. Levi 152 Bryant Howard 154 John S. Harbison.., 156 Col. Chalmers Scott i.S9 Charles Hubbell 162 George William Barnes, M. D, 170 O. S. Hubbell 164 Joseph Faivre . 167 Thomas L. Nesmith 172 Mrs. Mary J. Birdsall 175 D. Cave, D. D. S 176 Dr. W. A. Winder 179 Judge M. A. Luce. ... ...... 181 . LIST OF BIOGRAPHIES. George A. Cowles 184 Dr. P. C. Remondino 187 N. M. Conklin 190 R. A. Thomas 192 Judge John D. Works 194 L. S. McClure 197 Governor Robert W. Waterman 199 Col. W. H. Holabird 203 Col. John A. Helphingstine. 206 Willard N. Fos 208 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCHES- A. E. HORTON. It was the boast of Augustus Caesar that he found Rome in brick and he should leave it in marble. With more regard to truth might Alonzo E. Horton, speaking in the figurative style adopted by the Roman Emperor, remark that he found San Diego a barren waste, and to-day, as he looks down from the portico of his beautiful mansion on Florence Heights, he sees it a busy, thriving city of 35,000 inhabitants. -

Submitted to ATLANTIC HOME BUILDING and RENOVATION SECTOR COUNCIL

- FINAL REPORT- NOVA SCOTIA MANUFACTURED HOUSING INDUSTRY STUDY Submitted to ATLANTIC HOME BUILDING AND RENOVATION SECTOR COUNCIL by Thomas McGuire & Christina MacLean Peter Norman, Altus Clayton (formerly Clayton Research) John Jozsa, Jozsa Management & Economics David Sable & Associates May 26, 2008 Contact: Thomas McGuire (902) 431-697 T.M. McGuire Ltd. ● P.O. Box 22151, 7071 Bayers RPO ● Halifax, Nova Scotia ● B3L 4T7 e. [email protected] ● p. 902.431.6972 Nova Scotia Manufactured Housing Industry Study i Atlantic Home Building and Renovation Sector Council – Final Report/May 26, 2008 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Nationally, the manufactured housing industry represents between 1.5% and 2% of the total residential construction industry in Canada. The sector has grown at an average annual rate of 3.5% during the past decade as is worth some $1.5 billion annually to the Canadian economy. A total of 15,000 single family and 2,000 multi-units are manufactured in Canada each year with 20% destined for export and 80% destined for domestic sale. This study suggested that: Factory built homes presents a significant opportunity to achieve labour productivity gains in the residential construction industry. And Manufactured home building may present the most significant opportunity to overcome labour shortages in the residential construction sector. We suspect that labour market pressures and competing career choices, out migration of youth and other demographic challenges will continue pressure the construction labour market. Combined with the need for productivity gains, we anticipate that manufactured home building will continue to grow and that off- site construction work will provide homebuilders with an option to overcome limited supply of site build workers. -

Timberjig Big Mill LSG/PRO Big Mill BASIC

Read this manual before starting to use this equipment. This manual contains safety instructions. Warning! Failure to follow the instructions can cause serious injury. Timberjig BigBig MillMill BASICBASIC Big Mill LSG/PRO 1 2 Big Mill System Welcome to Logosol! We are pleased All the aluminium components have been anodized to offer that you have placed your trust in us a smooth, hard surface. Some of the steel components are by choosing the Timberjig, and we treated with nitrogen gas and hardened in oil, which gives promise to do our best to satisfy your the steel increased corrosion resistance, higher durability, expectations. low friction, and the characteristic black colour. Compared to typical zinc plating, this process is more expensive, but Logosol began production of our we feel that the resulting quality is both seen and felt. flagship product, the Logosol Sawmill, in 1988. Since then we have delivered We are just as concerned about your safety as we are about more than 15,000 sawmills to satisfied you getting the best results possible with your Timberjig. customers around the world. The first Timberjig was That is why we recommend you to read this manual from delivered in 1990. So far, every owner of a Timberjig we cover to cover before you begin sawing. Additionally, have talked to has been delighted with this simple, but the manual also contains helpful information which we functional, equipment. Many customers have, however, would like to pass down to you, gathered from our years looked for a product that is a little more outfitted than the of experience in sawing trees here in Sweden.