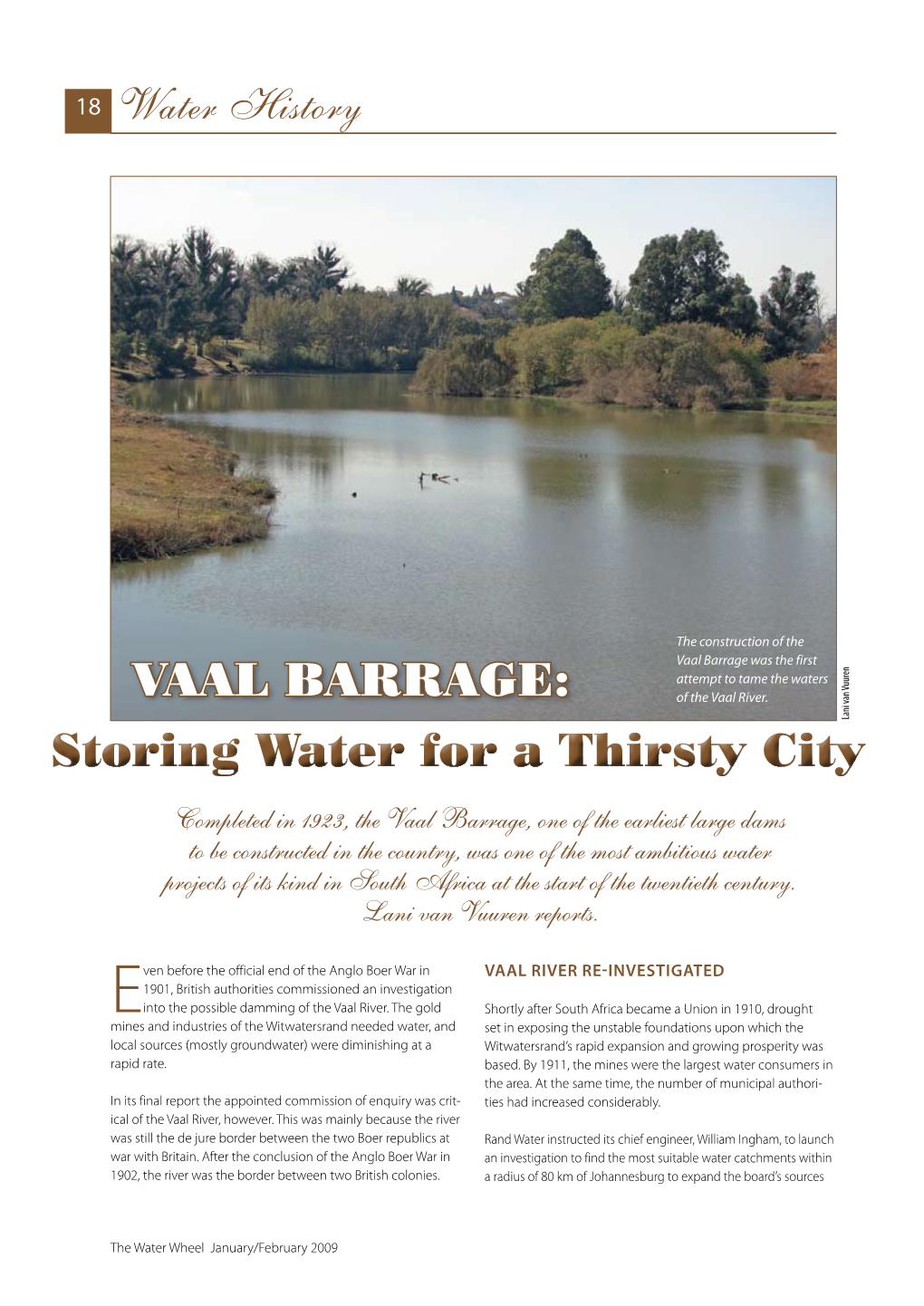

Storing Water for a Thirsty City Vaal Barrage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UPPER VAAL WATER MANAGEMENT AREA (WMA No 8)

Report Number: P WMA 08/000/00/0304 DEPARTMENT OF WATER AFFAIRS AND FORESTRY Directorate: National Water Resource Planning IInntteerrnnaall SSttrraatteeggiicc PPeerrssppeeccttiivvee UUppppeerr VVaaaall WWaateterr MMaannaaggeemmeenntt AArreeaa March 2004 Compiled by: W A T E R R E S O U R C E P L A N N I N G A N D C O N S E FC071R V A T I O N WRP Consulting Engineers (Pty) Ltd, Reg. No. 98/16706/07 WRP_FC332 ISP : UPPER VAAL WMA _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Department of Water Affairs and Forestry Directorate National Water Resource Planning INTERNAL STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVE FOR THE UPPER VAAL WATER MANAGEMENT AREA (WMA No 8) APPROVAL Title : Upper Vaal Water Management Area: Internal Strategic Perspective DWAF Report No : P WMA 08/000/00/0304 Consultants : PDNA, WRP Consulting Engineers (Pty) Ltd, WMB and Kwezi-V3 Report Status : Version 1 Version Controller : Mr Walther van der Westhuizen Date : March 2004 Approved for Consultants by: DEPARTMENT OF WATER AFFAIRS AND FORESTRY Directorate National Water Resource Planning Approved for Department of Water Affairs and Forestry by: ISP : UPPER VAAL WMA _________________________________________________________________________________________________________ REFERENCE This report is to be referred to in bibliographies as: Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, South Africa. 2004. Upper Vaal Water Management Area: Internal Strategic Perspective. Prepared by PDNA, WRP Consulting Engineers (Pty) Ltd, WMB and Kwezi-V3 on behalf of the Directorate: National Water Resource Planning. DWAF Report No P WMA 08/000/00/0304. INVITATION TO COMMENT This report will be updated on a regular basis until it is eventually superceded by the Catchment Management Strategy. -

Early History of South Africa

THE EARLY HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES . .3 SOUTH AFRICA: THE EARLY INHABITANTS . .5 THE KHOISAN . .6 The San (Bushmen) . .6 The Khoikhoi (Hottentots) . .8 BLACK SETTLEMENT . .9 THE NGUNI . .9 The Xhosa . .10 The Zulu . .11 The Ndebele . .12 The Swazi . .13 THE SOTHO . .13 The Western Sotho . .14 The Southern Sotho . .14 The Northern Sotho (Bapedi) . .14 THE VENDA . .15 THE MASHANGANA-TSONGA . .15 THE MFECANE/DIFAQANE (Total war) Dingiswayo . .16 Shaka . .16 Dingane . .18 Mzilikazi . .19 Soshangane . .20 Mmantatise . .21 Sikonyela . .21 Moshweshwe . .22 Consequences of the Mfecane/Difaqane . .23 Page 1 EUROPEAN INTERESTS The Portuguese . .24 The British . .24 The Dutch . .25 The French . .25 THE SLAVES . .22 THE TREKBOERS (MIGRATING FARMERS) . .27 EUROPEAN OCCUPATIONS OF THE CAPE British Occupation (1795 - 1803) . .29 Batavian rule 1803 - 1806 . .29 Second British Occupation: 1806 . .31 British Governors . .32 Slagtersnek Rebellion . .32 The British Settlers 1820 . .32 THE GREAT TREK Causes of the Great Trek . .34 Different Trek groups . .35 Trichardt and Van Rensburg . .35 Andries Hendrik Potgieter . .35 Gerrit Maritz . .36 Piet Retief . .36 Piet Uys . .36 Voortrekkers in Zululand and Natal . .37 Voortrekker settlement in the Transvaal . .38 Voortrekker settlement in the Orange Free State . .39 THE DISCOVERY OF DIAMONDS AND GOLD . .41 Page 2 EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES Humankind had its earliest origins in Africa The introduction of iron changed the African and the story of life in South Africa has continent irrevocably and was a large step proven to be a micro-study of life on the forwards in the development of the people. -

The Vaal River Inquiry Provisional Report

Final Report of the Gauteng Provincial Inquiry Into the Sewage Problem of the Vaal River 17 February 2021 The Vaal Report Executive Summary The South African Human Rights Commission (‘the Commission’) had been alerted to online and print media reports, published during July and August 2018, reporting that raw sewage, from the Emfuleni Local Municipality (‘the Municipality’)’s Rietspruit Waste Water Care and Management Works situated in Vanderbijlpark, the Leewkuil Waste Water Care and Management Works situated in Vereeniging and other areas within the Municipality, had for weeks and months been leaking into and polluting the Vaal River and the Rietspruit. In addition to the raw sewage polluting major and essential bodies of water, the media reports stated, amongst other things, that: the main sewers in Vanderbijlpark were blocked and that raw sewerage was flowing into people’s yards and properties. In September 2018, in order to test the veracity of the media reports, the Commission’s Gauteng Provincial Office conducted an inspection-in-loco at certain sites within the Emfuleni Municipality, and observed: raw sewage flowing in a small stream that cut across the Emfuleni Golf Estate; two burst sewerage pipes on the banks of the Rietspruit that runs through the Emfuleni Municipal area; defective bio-filters at the Rietspruit Waste Water Treatment Works; a clogged sewerage manhole at the Sharpeville Cemetery and children swimming in, and consuming, polluted waters in the area of a school. Having established a prima facie violation of human rights in the Emfuleni Municipality, regarding the flowing of raw, untreated sewage flowing in the streets, homes, graveyards and also flowing into the Vaal River, the Dam, the Barrage and the Rietspruit (referred to collectively as ‘the Vaal’), and acting within its legislative mandate, the Commission established an Inquiry. -

Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment

Study Name: Orange River Integrated Water Resources Management Plan Report Title: Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment Submitted By: WRP Consulting Engineers, Jeffares and Green, Sechaba Consulting, WCE Pty Ltd, Water Surveys Botswana (Pty) Ltd Authors: A Jeleni, H Mare Date of Issue: November 2007 Distribution: Botswana: DWA: 2 copies (Katai, Setloboko) Lesotho: Commissioner of Water: 2 copies (Ramosoeu, Nthathakane) Namibia: MAWRD: 2 copies (Amakali) South Africa: DWAF: 2 copies (Pyke, van Niekerk) GTZ: 2 copies (Vogel, Mpho) Reports: Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment Review of Surface Hydrology in the Orange River Catchment Flood Management Evaluation of the Orange River Review of Groundwater Resources in the Orange River Catchment Environmental Considerations Pertaining to the Orange River Summary of Water Requirements from the Orange River Water Quality in the Orange River Demographic and Economic Activity in the four Orange Basin States Current Analytical Methods and Technical Capacity of the four Orange Basin States Institutional Structures in the four Orange Basin States Legislation and Legal Issues Surrounding the Orange River Catchment Summary Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 General ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Objective of the study ................................................................................................ -

Labeo Capensis (Orange River Mudfish) Ecological Risk Screening Summary

Orange River Mudfish (Labeo capensis) Ecological Risk Screening Summary U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, 2014 Revised, May and July 2019 Web Version, 9/19/2019 Image: G. A. Boulenger. Public domain. Available: https://archive.org/stream/catalogueoffres01brit/catalogueoffres01brit. (July 2019). 1 Native Range and Status in the United States Native Range From Froese and Pauly (2019): “Africa: within the drainage basin of the Orange-Vaal River system [located in Lesotho, Namibia, and South Africa] to which it is possibly restricted. Hitherto thought to occur in the Limpopo system and in southern Cape watersheds [South Africa] which records may be erroneous.” From Barkhuizen et al. (2017): “Native: Lesotho; Namibia; South Africa (Eastern Cape Province - Introduced, Free State, Gauteng, Mpumalanga, Northern Cape Province, North-West Province)” 1 Status in the United States This species has not been reported as introduced or established in the United States. There is no indication that this species is in trade in the United States. Means of Introductions in the United States This species has not been reported as introduced or established in the United States. Remarks A previous version of this ERSS was published in 2014. 2 Biology and Ecology Taxonomic Hierarchy and Taxonomic Standing From ITIS (2019): “Kingdom Animalia Subkingdom Bilateria Infrakingdom Deuterostomia Phylum Chordata Subphylum Vertebrata Infraphylum Gnathostomata Superclass Actinopterygii Class Teleostei Superorder Ostariophysi Order Cypriniformes Superfamily Cyprinoidea Family Cyprinidae Genus Labeo Species Labeo capensis (Smith, 1841)” From Fricke et al. (2019): “Current status: Valid as Labeo capensis (Smith 1841). Cyprinidae: Labeoninae.” Size, Weight, and Age Range From Froese and Pauly (2019): “Max length : 50.0 cm FL male/unsexed; [de Moor and Bruton 1988]; common length : 45.0 cm FL male/unsexed; [Lévêque and Daget 1984]; max. -

19Th Century Tragedy, Victory, and Divine Providence As the Foundations of an Afrikaner National Identity

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History Spring 5-7-2011 19th Century Tragedy, Victory, and Divine Providence as the Foundations of an Afrikaner National Identity Kevin W. Hudson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Hudson, Kevin W., "19th Century Tragedy, Victory, and Divine Providence as the Foundations of an Afrikaner National Identity." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2011. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/45 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 19TH CENTURY TRAGEDY, VICTORY, AND DIVINE PROVIDENCE AS THE FOUNDATIONS OF AN AFRIKANER NATIONAL IDENTITY by KEVIN W. HUDSON Under the DireCtion of Dr. Mohammed Hassen Ali and Dr. Jared Poley ABSTRACT Apart from a sense of racial superiority, which was certainly not unique to white Cape colonists, what is clear is that at the turn of the nineteenth century, Afrikaners were a disparate group. Economically, geographically, educationally, and religiously they were by no means united. Hierarchies existed throughout all cross sections of society. There was little political consciousness and no sense of a nation. Yet by the end of the nineteenth century they had developed a distinct sense of nationalism, indeed of a volk [people; ethnicity] ordained by God. The objective of this thesis is to identify and analyze three key historical events, the emotional sentiments evoked by these nationalistic milestones, and the evolution of a unified Afrikaner identity that would ultimately be used to justify the abhorrent system of apartheid. -

Rivers of South Africa Hi Friends

A Newsletter for Manzi’s Water Wise Club Members May 2016 Rivers of South Africa Hi Friends, This month we are exploring our rivers. We may take them for granted but they offer us great services. Rivers provide a home and food to a variety of animals. You will find lots of plants, insects, birds, freshwater animals and land animals near and in a river. You can say rivers are rich with different kinds of living things. These living things play different roles such as cleaning the river and providing food in the river for other animals. Rivers carry water and nutrients and they play an important part in the water cycle. We use rivers for water supply which we use for drinking, in our homes, watering in farms, making products in factories and generating electricity. Sailing, taking goods from one place to another and water sports such as swimming, skiing and fishing happens in most rivers. Have you ever wondered where rivers begin and end? Well friends, rivers begin high in the mountains or hills, or where a natural spring releases water from underground. They usually end by flowing into the ocean, sea or lake. The place where the river enters the ocean, sea or lake is called the mouth of the river. Usually there are lots of different living things there. Some rivers form tributaries of other rivers. A tributary is a stream or river that feeds into a larger stream or river. South Africa has the following major rivers: . Orange River (Lesotho, Free State & Northern Cape Provinces), Limpopo River (Limpopo Province), Vaal River (Mpumalanga, Gauteng, Free State & Northern Cape Provinces), Thukela River reprinted with permission withreprinted (Kwa-Zulu Natal Province), Olifants River – (Mpumalanga & Limpopo Provinces), Vol. -

THE IMPACT of ALGAE and CYANOBACTERIAL BLOOMS on SOUTH-AFRICAN FRESHWATERS Sanet Janse Van Vuuren

THE IMPACT OF ALGAE AND CYANOBACTERIAL BLOOMS ON SOUTH-AFRICAN FRESHWATERS Sanet Janse van Vuuren Division Botany School of Environmental Sciences and Development North-West University Potchefstroom SOUTH AFRICA ALGAE AND CYANOBACTERIAL BLOOMS IN SOUTH AFRICAN FRESHWATERS Introduction • Availability of fresh water – most limiting factor • Rainfall less than 500 mm/year • One of the 30 driest countries in the world • Only three large rivers Limpopo Vaal Orange http://www.dwaf.gov.za/iwqs/gis_data/river/all.jpg ALGAE AND CYANOBACTERIAL BLOOMS IN SOUTH AFRICAN FRESHWATERS Introduction • Availability of fresh water – most limiting factor • Only three large rivers • Almost 200 dams (man-made): • Limpopo – 27 • Mpumalanga – 23 • KwaZulu Natal – 15 • Gauteng – 4 • North West – 20 • Free State – 30 • Eastern Cape – 29 • Northern Cape – 5 • Western Cape - 45 http://www.dwaf.gov.za/orange/images/web179l.jpg ALGAE AND CYANOBACTERIAL BLOOMS IN SOUTH AFRICAN FRESHWATERS Introduction http://www.dwaf.gov.za/orange/images/web179l.jpg ALGAE AND CYANOBACTERIAL BLOOMS IN SOUTH AFRICAN FRESHWATERS Introduction The Gariep Dam, in the Free State, is the dam with the largest storage capacity (5 500 million m3) ever built in South Africa. Constructed in 1972, it stores water from the Orange River in a 100 km-long dam with a surface area of 374 km2. http://www.dwaf.gov.za/orange/images/web179l.jpg ALGAE AND CYANOBACTERIAL BLOOMS IN SOUTH AFRICAN FRESHWATERS Introduction • Mixed algal assemblage • Research on the Vaal River: – Chlorophyta and Bacillariophyta – -

Water Management at a Large Opencast Strip Coal Mine in South Africa

8th International Congress on Mine Water & the Environment, Johannesburg, South Africa Water management at a large opencast strip coal mine in South Africa D.A. Salmon Principal Engineer, Anglo American Technical Division, Civil Engineering Department PO Box 61587, Marshalltown 2107, South Africa. #$564#%6 Water is a scarce resource in Southern Africa. Potential mining impacts on this resource are crucial to the management of water on the national scale. This paper describes the water management issues and approaches taken by Anglo Coal’s New Vaal Colliery from mine planning through to the full operational stage of the mine. New Vaal Colliery produces up to 15 million sales tons of coal per annum from an opencast strip operation developed adjacent to large residential and industrial areas and to the Vaal Barrage, a strategic surface water resource in Gauteng Province. The mining area also overlies the largest and most utilised aquifer in South Africa, the Transvaal Dolomite. Opencast strip mining takes place in three seams previously mined by underground bord and pillar methods and which were flooded by water treatment effluent prior to re mining. Opencast mining commenced in 1984. This paper describes the geohydrology, water management challenges and the management measures used to overcome the issues of mine flood control, mine drainage, and the prevention of surface and ground water pollution. The hydrology and the geohydrology, the results of water monitoring, pump testing, mine water chemistry determinations, ground water and surface water modeling, prediction of the post mining water scenarios are detailed. In particular, the relationship between three aquifers, river alluvium, Karoo rocks and the Dolomite and the flooded underground workings is described. -

Main Pollutants in the Vaal River Barrage Over the Past 20 Years

SEASONAL RAINFALL INFLUENCES ON MAIN POLLUTANTS IN THE VAAL RIVER BARRAGE RESERVOIR: A TEMPORAL- SPATIAL PERSPECTIVE By ESTIE OCHSE MINOR DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree MAGISTER ARTIUM In ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT In the FACULTY OF HUMANITIES at the UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG Supervisor: Prof. J.T. Harmse 2007 Page i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the following persons for their help and encouragement: o My husband Stefan for his patience and tremendous help during the whole process; o My mother for her ongoing support; o Prof. Harmse for his guidance; and o Mr. F. van Wyk, Head: Catchment Management of Rand Water for providing the water quality monitoring data. Page - ii - ABSTRACT South Africa is situated within a semi-arid part of the world which is characterised by high seasonal variability in terms of rainfall and runoff, with high evaporation rates. This causes streamflow to be relatively low for most of the year, with seasonal sporadic high flows. Further stress is applied to the water resource through population growth, increased urbanisation and industrial activities. The study area is considered to be the most populated of the Upper Vaal Water Management Area (WMA), which is the most important WMA in terms of economic productivity in South Africa. This research report focused on assessing the temporal and spatial variations of pollution between four different sampling points located in the Vaal Barrage Reservoir, which is located in the heart of the Upper Vaal WMA. The Vaal River Barrage Reservoir forms a 64 kilometres long water body with an estimated total storage capacity of 63 million litres of water. -

Johannesburg – City on a Watershed

Urban water supply JOHANNESBURG – City on a watershed 18 The Water Wheel May/June 2011 Urban water supply Johannesburg’s location is both its gift and also a metaphorical one – changing sprang up to house the thousands of its curse – close to the gold, but far from from a water-secure to a possibly people seeking their fortune. water insecure city. Originally, water was drawn from water. Article by Petro Kotzé. the Fordsburgspruit, as well as from SMALL BEGINNINGS a spring at the eastern end of Com- ohannesburg’s location is both missioner Street, near the present its gift and its curse. On the one ohannesburg is situated on a day End Street, called Natalspruit. hand, the gold-bearing reef that Jdivide between the Vaal River Another water point was a spring at Jis the reason for its existence has catchment (the Vaal itself being a the site of the present Johannesburg shaped it into the economic heart- tributary of the Orange River) and general hospital in Parktown. With land of the country. On the other the Limpopo River catchment. On the expansion of mining activities, hand, it is one of the few cities in the one side, water runs down the Vaal industrial development, pollution world not located close to one of the and the Orange towards the Atlantic, and population growth, the demand most important resources necessary while on the other side water drains for potable water grew. Soon, the to sustain its growth: water. towards the Indian Ocean via the rivulets and boreholes were inade- Indeed, where other major cities Limpopo River system. -

The Current Limited Impact of Witwatersrand Gold-Mine Residues on Water Pollution in the Vaal River System by D.D

J. S. At,. Inst. Min. Metal/., vol. 86, no. 12. Dec. 1986. pp. 481-504. The current limited impact of Witwatersrand gold-mine residues on water pollution in the Vaal River system by D.D. MARSDEN* SYNOPSIS This paper discusses the concentrations of sulphides and total sulphur in widely spread regions around mine residue deposits, from which rain-water run-off can enter the Vaal River system. Analyses of borehole samples from several deposits are used to establish typical sulphur head grades. It is shown that a high percentage of all the oxidizable, and hence leachable and pollution-<:ausing, sulphur has already been removed. When the residues were fresh, water that came from the deposits was highly polluted, but the dissolved solids from these residues are today of very minor significance. The data are supported by analyses of the drainage streams. SAMEVATTING Hierdie referaat bespreek die sulfied- en totale swaelkonsentrasie in wydverspreide gebiede om mynresiduafsettings vanwaar afloopreenwater in die Vaalrivierstelsel kan beland. Ontledings van boorgatmonsters van verskeie afset- tings word gebruik om tipiese toevoergrade vir swael te bepaal. Daar word getoon dat 'n hoe persentasie van al die oksideerbare en dus uitloogbare swael wat besoedeling veroor- saak, reeds verwyder is. Toe die residu's vars was, was die water wat van die afsettings gekom het, erg besoedel, maar die opgeloste vaste stowwe afkomstig van hierdie residu's is tans van baie min belang. Die data word gestaaf deur ontledings van die dreineerstrome. Introduction As mining activity on the Witwatersrand increased dustrial Research undertook an extensive survey of the from the turn of the century, so did the contamination Witwatersrand catchment area of the Vaal River.