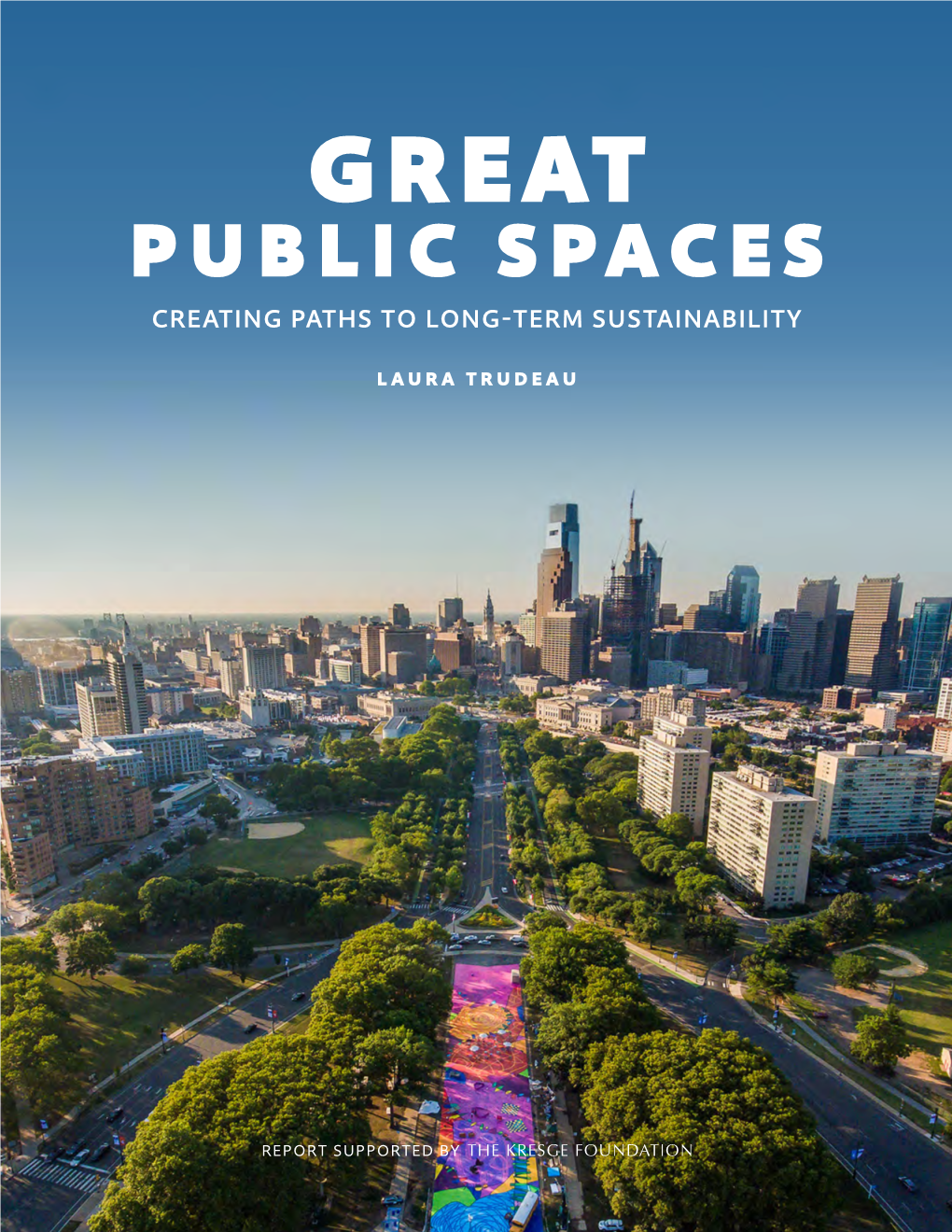

Great Public Spaces: Creating Paths to Long-Term Sustainability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to The

GUIDE TO THE If you are looking for a place to live during your time in the D, you have a rich variety of neighborhoods to choose from, each with their own personalities, history, and amenities. Please refer to the below guide, written by our residents, to help you choose the best place to enjoy the city and people! Created by James Jermls VandenBerg MD & The Residents of DRH Neighborhoods Downtown If you want to fully experience the D, then this is the place for you. The city is experiencing a unique renaissance as historic buildings have been renovated, new restaurants and bars continue to flourish, and large scale murals decorate the faces of our skyscrapers. If you enjoy the hustle and bustle of city life and want to celebrate the most resilient city in the country, then you should find yourself here. o Pros: Not only are you in the heart of all the action, more importantly you can get to work in about 5-10 minutes. There’s a wealth of new and historic bars and restaurants in every direction. This includes Campus Martius Park, which is in the center of downtown and converted into a beach bar in the summer and an ice- skating rink in the winter! You are in the center of all the major attractions in the area, including proximity to all professional Detroit sports, landmark buildings/sculptures to explore, and it’s very dog friendly with numerous dog parks. It borders the Detroit River with multiple running trails including the Dequindre Cut. If you like to gamble there are multiple casinos, and if you like feta and moussaka we have Greektown; o Cons: Generally more expensive than other neighborhoods, and almost exclusively apartment-high-rise living (the city is your backyard now). -

Apartment Features

Welcome Bienvenido Chào Mừng Quý Vị 欢迎 Bienvenue Modern Living in New Center Welcome to The Boulevard in Detroit’s New Center, featuring modern rental apartments located in the heart of an international city, in a neighborhood of professional institutions and cultural gems. With its walkability and access to public transportation and major expressways, The Boulevard is home to long-term Detroiters, new residents, and visitors. The Boulevard offers attached parking, ground floor retail and restaurants, and is both family and pet friendly. 01 Apartment Features The Boulevard offers 231 apartments with a variety of studio, 1, and 2 bedrooms layouts featuring: Modern Design Wood Style Flooring Stainless Appliances Dishwasher Air Conditioning Walk In Closets In Home Laundry Private Balconies* *Available in Select Apartments 03 Community Amenities Situated on 1.5 acres in New Center, The Boulevard provides five floors of high-quality residential over ground floor retail. City Views Ground Floor Retail Controlled Access Entry Fitness Center Club Room Lounge Room BBQ Terrace Interior Courtyard Attached Parking* Bike Storage & Repair* Storage Lockers* Pet Friendly *Available to Rent 05 Clairmont Ave In the Neighborhood 2nd Ave 3rd Ave 45 52 51 51 Lothrop St 53 New Center 6 50 Brush St 34 17 57 Anchor Institutions Food & Drink Fisher 55 20 1 Cadillac Place 11 Avalon Café & Biscuit Bar 1 Building 56 4 11 8 2 College for Creative Studies 12 Bucharest Grill 42 14 3 Detroit Medical Center 13 Chartreuse Kitchen & Cocktails 15 21 12 49 4 Henry Ford Hospital -

ITINERARY TSKW Detroit Arts Trip FINAL 18.5.30

FINAL ITINERARY FOR 2018 TSKW ARTS & CULTURE TRIP TO DETROIT Monday 20 August thro Friday 24 August Day 1 – Mon Aug 20 Travel to destination Check in at the Detroit Foundation Hotel, Larned Street, Detroit 313-915-4422 www.detroitfoundationhotel.com 5:45pm Welcome cocktail party and private dinner at Hotel With presentation by Local Art Historian to provide background for our week of Arts & Culture in Detroit Day 2 – Tue Aug 21 Breakfast – on your own 8:45 walk to trolley station at Congress at Woodward to Detroit Institute for the Arts 9:15 Meet with the Executive Director followed by Private guided tour of DIA (Detroit Institute for the Arts) The Detroit Institute of Arts has one of the largest and most significant art collections in the United States. With more than 65,000 artworks that date from the earliest civilizations to the present, the museum offers visitors an encounter with human creativity from all over the world. 11:30am -Lunch at the DIA in Dining Room B www.dia.org 1pm Bus picks up at DIA to take us to Motown Museum Afternoon 1:30pm Tour of The Motown museum Originally the recording studios and residence of Berry Gordy and Motown Records. Information for visitors to the museum, and profiles of the label's featured artists including Stevie Wonder, The Supremes, Jackson 5, and Four Tops. Located in Detroit, Michigan, US www.Motownmuseum.org Take bus back to hotel for freshen up 4:30pm Promptly Bus picks up from hotel to take us to Bay View Yacht Club for Private yacht & dinner trip down Detroit river to view the beautifully renovated River park. -

What's Free in the D Metro Detroit on a Budget

https://visitdetroit.com/itinerary/whats-free-d-metro-detroit-budget/ What's Free in The D Metro Detroit on a Budget We all know there’s fun in metro Detroit on a budget — Tigers value packs, cheap lawn seats at DTE Energy Music Theatre or happy hour specials at favorites such as Roast, Cliff Bell’s, Ottava Via and La Feria — but what about those days when you want to do something, and you just don’t feel like spending anything? No problem. Our Free in The D tips and to-dos let you leave your worries (and wallets) behind. TAKE YOUR TIME FEATURES DESTINATIONS Entertainment, Sports & Downtown Detroit, Greater Recreation Novi, Macomb, Oakland 1 EASTERN MARKET No trip to The D is complete without spending time at Eastern Market, where every Saturday (since 1891), thousands of people mingle amid six blocks of local goodness. With more than 250 independent vendors and merchants, you’ll find fresh vegetables, fruits, fish, meat, flowers and more. Sometimes you might score a vendor sample or two. Check out our feature story for more great things to do in Eastern Market. https://visitdetroit.com/itinerary/whats-free-d-metro-detroit-budget/ 2 ART, STATUES & OTHER DETROIT FIXTURES If art appreciation in the outdoors is your thing, Detroit has a great group of sculptures and unique art installations on street corners, in front of buildings and as focal points in urban parks. No cost for stopping, staring and admiring, of course. Some of the city’s most iconic must-sees: The Memorial to Joe Louis (The Fist) on Jefferson Avenue Spirit of Detroit on Woodward Avenue Dodge Memorial Fountain in Hart Plaza Larger-than-life tiger statue at Comerica Park Giant Uniroyal Tire along I-94 expressway near Allen Park Less than a buck: Ride the Detroit People Mover and catch the great art at each of the 13 stops. -

Discover Detroit Patch Program Flyer

- 0am= ClI,, am=l&I CJi:» i5 GSSEM Discover Detroit Detroit is the largest city in the state of Michigan and the largest American city on the United States/ Canadian border. Detroit is a major port located on the Detroit River, one of the four major straits that connect the Great Lakes system to the Saint Lawrence Seaway. It has a diverse population and culture. New hotels, scenic and social parks, public transit, bike lands and the walkable riverfront are redefining Detroit. There are so many things to see and do! Food � Have lunch at the Bucharest Grill. � Partake in your own Coney War – who has the better coney: American or Lafayette? � Find a new restaurant in Detroit and write a yelp review. � There are many ethnic restaurants in Detroit, visit one. What is your favorite? Share with a friend or family member. � Participate in Detroit’s Restaurant Week. � What food and drink are home to Detroit? Events � Go to a Special Event in the city: Winter Blast, Auto Show, Greek Independence Day Parade, Belle Isle Grand Prix, River Days, the America’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. � Attend an event at the New Center Park on West Grand Blvd. � Attend the Detroit International Jazz Festival with your family. � See a show at the FOX or Fisher Theater. � Go to a game (Football, Hockey, Baseball, Basketball) or a concert. � Run a marathon or race (could just be a 5K) downtown or volunteer at one in Detroit. Tours � Take a tour of the Parade Company. � Tour the Girl Scouts of Southeastern Michigan Headquarters (schedule with your Troop Support Specialist). -

Report No. Cl36735-1 Michigan Department of Licensing

REPORT NO. CL36735-1 'C' SALES BY DESCENDING SALES PAGE 1 MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF JAN THRU DEC 2017 PERIOD covered" LICENSING & REGULATORY AFFAIRS 01/01/2017 THRU 12/31/2017 LIQUOR CONTROL COMMISSION DATE PRODUCED: 03/08/2018 LICENSE BUS ID CITY NAME OF BUSINESS SALES 01-002944 1885 Grand Rapids THE B.O.B. 752, 977.. 98 01-280984 249412 Detroit LITTLE CAESARS ARENA 693, 284 ,.23 01-250700 239108 Dearborn THE PANTHEION CLUB 532, 028 ..60 01-249170 238177 Detroit LEGENDS DETROIT 504, 695..69 01-005386 3518 Detroit FLOOD'S ■ 488, 822 . 05 01-256665 234992 Detroit STANDBY DETROIT, THE SKIP 459, 768..53 01-074686 129693 Detroit COMERICA PARK COMPLEX AND BALL PARK 447, 909.. 90 01-256954 240691 Detroit THE COLISEUM 425, 835 . 72 01-176176 211480 Southfield .7 BAR GRILL 410, 974.43 01-171141 208056 Walled Lake UPTOWN GRILLE, LLC ■ 410, 096.90 01-205709 190692 Detroit THE PENTHOUSE CLUB 403, 166..39 01-009249 6026 West Bloomfield SHENANDOAH GOLF & COUNTRY CLUB 395, 079..24 01-212753 225737 Ferndale WOODWARD IMPERIAL 381, 516 ..39 01-222359 223327 Royal Oak FIFTH AVENUE 3.76, 272..34 01-244491 236827 Detroit PUNCH BOWL SOCIAL-DETROIT 362, 291.. 41 01-252261 238977 Detroit TOWNHOUSE 336, 972.86 01-230927 232496 Birmingham MARKET NORTH END 331, 212.36 01-192070 223065 Detroit RUB BBQ 330, 264.52 .01-187582 214921 Detroit STARTERS BAR & GRILL AT STUDIO ONE 322, 071.46 01-007005 4566 Detroit NIKKI'S PIZZA 321, 873.10 01-000586 381 Detroit GOLDEN FLEECE 320, 830.50 01-107843 132852 Royal Oak O'TOOLES TAVERN 317, 264.91 01-267109 244173 Southfield DUO -

A Report on Greater Downtown Detroit 2Nd Edition

7.2 A Report on Greater Downtown Detroit SQ MI 2nd Edition CONTRIBUTORS & CONTENTS Advisory Team Keegan Mahoney, Hudson-Webber Foundation Elise Fields, Midtown Detroit Inc. James Fidler, Downtown Detroit Partnership Spencer Olinek, Detroit Economic Growth Corporation Jeanette Pierce, Detroit Experience Factory Amber Gladney, Invest Detroit Contributors Regina Bell, Digerati Jela Ellefson, Eastern Market Corporation Phil Rivera, Detroit Riverfront Conservancy Data Consultant Jeff Bross, Data Driven Detroit Design Megan Deal, Tomorrow Today Photography Andy Kopietz, Good Done Daily Production Management James Fidler & Joseph Gruber, City Form Detroit 2 7.2 SQ MI | A Report on Greater Downtown Detroit | Second Edition 04 Introduction 06 Section One | Overview 08–09 Greater Downtown in Context 10–11 Greater Downtown by Neighborhood 12–25 Downtown, Midtown, Woodbridge, Eastern Market, Lafayette Park, Rivertown, Corktown 26 Section Two | People Demographics 28 Population & Household Size 29–30 Density 31 Age 32–33 Income 34 Race & Ethnicity 35 Foreign-Born Education 36 Young & College-Educated 37 Residence of Young Professionals 39 Families 40 Programs for Young Professionals 41 Anchor Academic Institutions Visitors 42–43 Visitors & Venues 45 Hotels & Occupancy 46 Section Three | Place Vibrancy 48–63 Amenities & Necessities 64–65 Pedestrians & Bicycles Housing 66–69 Units & Occupancy 70–71 Rents 72 Incentives 74 Section Four | Economy & Investment Employment 76 Employment, Employment Sectors & Growth 77 Wages 78–80 Commercial Space 82–91 Real Estate Development 92 Note on Data 94 Sources, Notes & Definitions Contributors & Contents 3 INTRODUCTION 7.2 square miles. That is Greater Downtown Detroit. A slice of Detroit’s 139-square mile geography. A 7.2 square mile collection of neighborhoods: Downtown, Midtown, Woodbridge, Eastern Market, Lafayette Park, Rivertown, and Corktown—and so much more. -

Detroit Insider's Map + Guide

DETROIT INSIDER’S MAP + GUIDE EAT, SHOP, STAY + PLAY SEE THE OVERVIEW USING MAP AT THE END OF THIS THE GUIDE GUIDE Detroit Insider's Map + Guide is a THIS IS GREATER resource to help you connect with DOWNTOWN AND KEY NEIGHBORHOOD downtown Detroit and surrounding DESTINATIONS BEYOND THE CENTER neighborhoods. It highlights key DOWNTOWN destinations for business, retail, GREEKTOWN Though only a small part of MEXICANTOWN Detroit’s 139-square-mile geography, this is a collection food and fun. CORKTOWN of neighborhoods in the city RIVERTOWN center and beyond. Like many THIS GUIDE IS Detroit Metro Convention EASTERN MARKET city centers globally, greater BROUGHT TO YOU & Visitors Bureau (DMCVB) MIDTOWN downtown Detroit is a nexus BY DDP & DMCVB is an independent, nonprofit AVENUE OF FASHION of activity — welcoming Downtown Detroit Partnership economic development residents, employees and (DDP) plans, manages and organization. Its mission visitors. Downtown contains supports downtown Detroit is to market and sell the Detroit high-rise and low-rise living, through diverse, resilient metropolitan region to business some of the city’s most storied and economically urban and leisure visitors in order to CONTENTS neighborhoods and many of initiatives. It is a member- maximize economic impact. DDP PROGRAMS + southeast Michigan’s leading based nonprofit working in In collaboration with our RESOURCES 2 educational and medical partnership with corporate, partners, stakeholders and DETROIT EXPERIENCE institutions. Greater downtown philanthropic and government customers, our purpose is to FACTORY TOURS 4 Detroit is the center of the entities to create a vibrant champion the continuous DOWNTOWN 5 city’s business world, home to and world-class urban core improvement of the region our richest cultural, sports and in downtown Detroit. -

Report No. Cl36735-1 Michigan Department of Licensing

\ REPORT NO. CL36735-1 'C' SALES BY DESCENDING SALES PAGE 1 MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF JAN THRU DEC 2018 PERIOD COVERED LICENSING & REGULATORY AFFAIRS 01/01/2018 THRU 12/31/2018 LIQUOR CONTROL COMMISSION DATE PRODUCED: 02/12/2019 LICENSE BUS ID CITY NAME OF BUSINESS SALES 01-002944 1885 Grand Rapids THE B.O.B. 709,931.05 01-280984 249412 Detroit LITTLE CAESARS ARENA 641,911.05 01-250700 239108 Dearborn THE PANTHEION CLUB 627.591.33 01-256665 234992 Detroit STANDBY DETROIT, THE SKIP 532,445.65 01-249170 238177 Detroit LEGENDS DETROIT 532,019.80 01-005386 3518 Detroit FLOOD'S 510,669.05 01-234985 234777 Birmingham 220 MERRILL 510,044.27 01-171141 208056 Walled Lake UPTOWN GRILLE, LLC 439,080.95 01-192070 223065 Detroit RUB BBQ 431.915.22 01-256954 240691 Detroit THE COLISEUM 429,019.71 01-009249 6026 West Bloomfield SHENANDOAH GOLF & COUNTRY CLUB 387,744.44 01-205461 225400 Detroit THE GREEK 387,691.64 01-267109 244173 Southfield DUO RESTAURANT & LOUNGE 379.647.41 01-233240 232272 Detroit SCORES DETROIT 377.941.25 01-000586 381 Detroit GOLDEN FLEECE 362,424.10 01-244491 236827 Detroit PUNCH BOWL SOCIAL-DETROIT 358.965.23 01-230927 232496 Birmingham MARKET NORTH END 350,802.14 01-222359 223327 Royal Oak FIFTH AVENUE 346.233.33 01-074686 129693 Detroit COMERICA PARK COMPLEX AND BALL PARK 341,200.62 01-212753 225737 Ferndale WOODWARD IMPERIAL 336.624.75 01-217142 228018 Ann Arbor LAST WORD ANN ARBOR 310.766.26 01-259437 242326 Detroit 800 PARC, LLC 299,553.00 01-004668 3048 Inkster THE FLIGHT CLUB 298.404.75 01-162396 193177 Ann Arbor GOOD TIME -

Guide to The

GUIDE TO THE If you are looking for a place to live during your time in the D, you have a rich variety of neighborhoods to choose from, each with their own personalities, history, and amenities. Please refer to the below guide, written by our residents, to help you choose the best place to enjoy the city and people! James “Jermls” VandenBerg MD, MSc Neighborhoods: Downtown: If you want to fully experience the D, then this is the place for you. The city is experiencing a unique renaissance as historic buildings have been renovated, new restaurants and bars continue to flourish, and large scale murals decorate the faces of our skyscrapers. If you enjoy the hustle and bustle of city life and want to celebrate the most resilient city in the country, then you should find yourself here. o Pros: Not only are you in the heart of all the action, more importantly you can get to work in about 5-10 minutes. There’s a wealth of new and historic bars and restaurants in every direction. This includes Campus Martius Park, which is in the center of downtown and converted into a beach bar in the summer and an ice- skating rink in the winter! You are in the center of all the major attractions in the area, including proximity to all professional Detroit sports, landmark buildings/sculptures to explore, and it’s very dog friendly with numerous dog parks. It borders the Detroit River with multiple running trails including the Dequindre Cut. If you like to gamble there are multiple casinos, and if you like feta and moussaka we have Greektown; o Cons: Generally more expensive than other neighborhoods, and almost exclusively apartment-high-rise living (the city is your backyard now). -

The Boulevard 2911 WEST GRAND BOULEVARD, DETROIT

The Boulevard 2911 WEST GRAND BOULEVARD, DETROIT RETAIL SPACE AVAILABLE FOR LEASE PLATFORM LEASING & BROKERAGE 2 THE BOULEVARD THE PLATFORM 3 The Boulevard 2911 WEST GRAND BOULEVARD, DETROIT The Boulevard is a newly constructed mixed-use development at the corner of West Grand Boulevard and Third Avenue in New Center. Ideally located in a neighborhood of professional institutions and cultural gems, The Boulevard is walking distance to Henry Ford Hospital, Fisher Building, several large office buildings, two universities and is less than two blocks from QLine streetcar and MoGo electric bike stations. The Boulevard is also less than a mile from major area expressways. The six-story building is highly visible with its modern design and varied use of brick, metal and glass. First floor retail spaces feature large window walls to engage and invite the community inside. A discreet attached parking structure services residents, visitors and retailers. Stage of Development NEIGHBORHOOD PROJECT TYPE TOTAL RETAIL New Center Residential & Retail 17,500 SF ADDRESS TOTAL SIZE AVAILABLE RETAIL 2911 W. Grand Boulevard 207,000 SF 8,395 SF DATE COMPLETE RESIDENTIAL PARKING Fall 2019 231 Units 330 Spaces in structure [email protected] theplatform.city THE UP DN GATE 4 THE BOULEVARD THE PLATFORM 5 330 PARKING SPACES IN ATTACHEDRETAIL/RESIDENTIAL STRUCTURE PARKING 82 SPACES FD FD FD FD ORANGETHEORY BEYOND STEAVAILABLE 120 STEAVAILABLE 115 STE 112 STE 110 BEYOND JUICE RETAIL RETAIL AVAILABLE RETAIL AVAILABLE RETAIL COMERICA 3RD AVE. ORANGE THEORY FITNESS SALESRESIDENTIAL CENTER CANOPY, DN COMERICA FITNESS3,797 SF 2,300 SF UP JUICE2,011 SF 2,1532,153 SFSF 1,649~1,750 SF SF 2,018~1,850 SFSF 2,5752,575 SF SF 3,500 SF ABOVE LEASING ELEV OFFICEE103 RESIDENT ENTRY CANOPY, CANOPY, ABOVE CANOPY, ABOVE ABOVE W. -

VISIT DETROIT MAGAZINE Multiple Copy Discounts Are Available

THE ULTIMATE GUIDE FOR EVERYTHING TO SEE AND DO IN THE D APRIL-SEPTEMBER 2020 SUMMER & For additional video content, P. 46 open your camera app, point it at the A SHOW QR CODE and tap The North American the notification. International Auto Show says hello to Detroit this June. SPRING & SUMMER 2020 / APRIL-SEPTEMBER CONTENTS Where Do Those In The Know Go? 38 EXPLORE THE BIRTHPLACE OF THE MODEL T 46 THE FORD PIQUETTE AVENUE MUSEUM Hello, Auto Show. • Conveniently located in the heart of Milwaukee Junction HOURS Meet Summer. inside Detroit’s New Center Wednesday to Sunday:10 am – 4 pm (Closed Monday and Tuesday) FROM THE CHAIRMAN 2 The Bricks THE ULTIMATE GUIDE FOR EVERYTHING TO SEE AND DO IN THE D 22 VISIT DETROIT • Steps from Woodward Avenue and the QLine Commuter Pizzeria Optional guided tours: 10 am | 12 pm | 2 pm ONLINE 5 Rail System Closed: Jan. 1 | Easter | July 4 | SOUVENIRS 112 APRIL-SEPTEMBER 2020 SUMMER & For additional video content, P. 46 open your camera Thanksgiving Day | December 24, 25, 31 app, point it at the A SHOW QR CODE and tap the notification. • Free parking NAIAS 2020 • TRENDSETTERS’ GUIDE TO DETROIT The North American International Auto Show says hello to Detroit Private and group tours are available year- this June. • Over 60 Early Automobiles on Display EXPERIENCE 7 round. Call 313-872-8759 for reservations. THE D 8 • Hands-on Exhibits ITINERARIES 32 ADMISSION REASONS TO LOVE THE D 36 SPRING & SUMMER SPRING & SUMMER 2020 RECOGNITION Adults: $15 | Seniors (65+): $10 HIGHLIGHTS TO DO 53 • A dedicated site within the MotorCities National Heritage Veterans: $10 | Students (with ID): $10 Youth (5-17): $5 | Children (4 & Under): Free APRIL-SEPTEMBER EVENTS 54 About the cover RECURRING EVENTS 66 WHERE DO THOSE Area, 1996 Group Tours (10 minimum): $10 each For the first time in LOOKING AHEAD 67 IN THE KNOW GO? 38 its 100-year history, Blue Star Museum • U.S.