PDF Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literature of the Low Countries

Literature of the Low Countries A Short History of Dutch Literature in the Netherlands and Belgium Reinder P. Meijer bron Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries. A short history of Dutch literature in the Netherlands and Belgium. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague / Boston 1978 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/meij019lite01_01/colofon.htm © 2006 dbnl / erven Reinder P. Meijer ii For Edith Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries vii Preface In any definition of terms, Dutch literature must be taken to mean all literature written in Dutch, thus excluding literature in Frisian, even though Friesland is part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, in the same way as literature in Welsh would be excluded from a history of English literature. Similarly, literature in Afrikaans (South African Dutch) falls outside the scope of this book, as Afrikaans from the moment of its birth out of seventeenth-century Dutch grew up independently and must be regarded as a language in its own right. Dutch literature, then, is the literature written in Dutch as spoken in the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the so-called Flemish part of the Kingdom of Belgium, that is the area north of the linguistic frontier which runs east-west through Belgium passing slightly south of Brussels. For the modern period this definition is clear anough, but for former times it needs some explanation. What do we mean, for example, when we use the term ‘Dutch’ for the medieval period? In the Middle Ages there was no standard Dutch language, and when the term ‘Dutch’ is used in a medieval context it is a kind of collective word indicating a number of different but closely related Frankish dialects. -

From Holland and Flanders

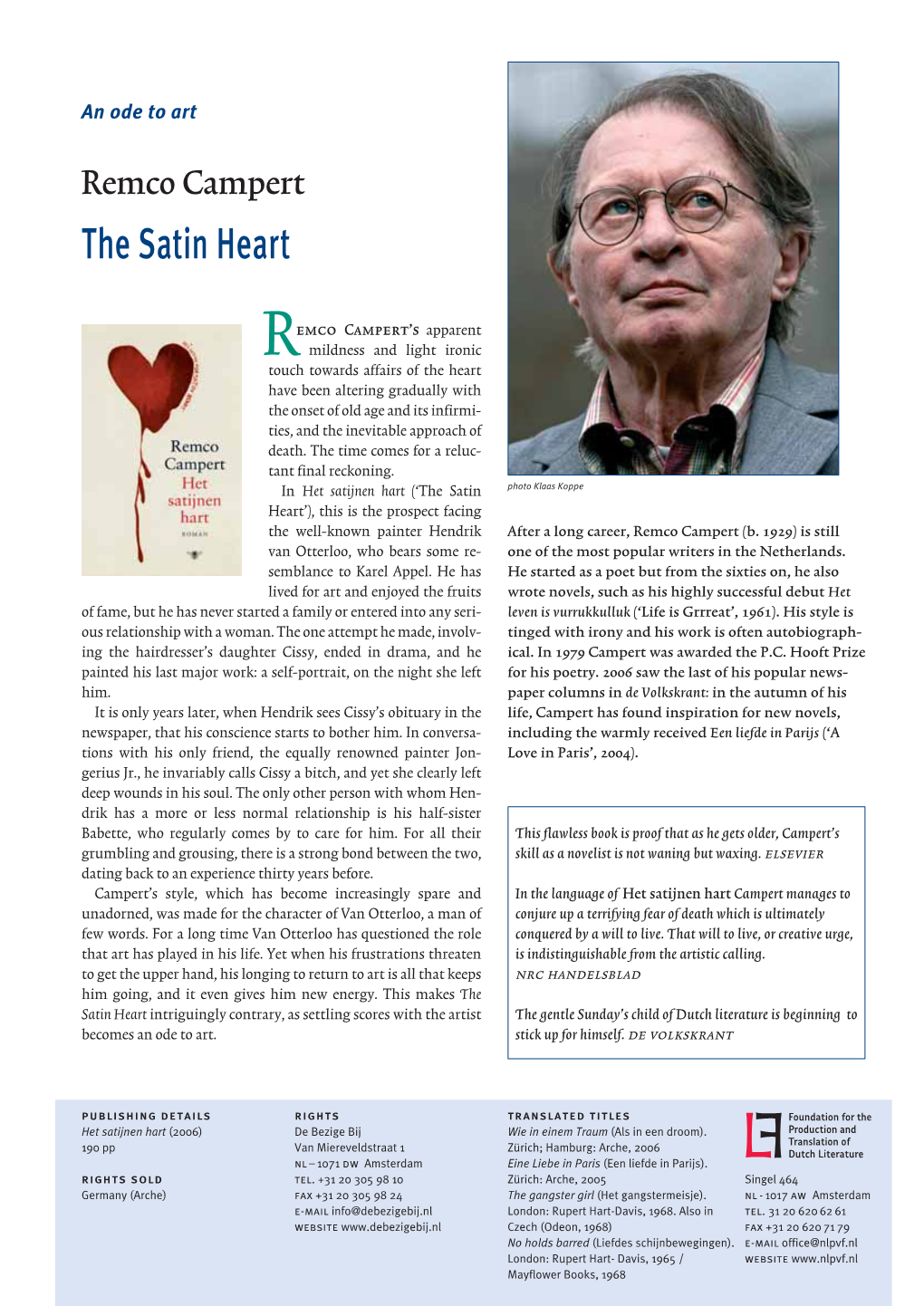

qg no. 15-2 10 Bookautumns 2006 from Holland and Flanders Gerbrand Bakker Remco Campert Dimitri Verhulst Michael Frijda K. Schippers Sana Valiulina Pieter Toussaint Geert Kimpen Elvis Peeters Christiaan Weijts qg 2 A gem of a first novel Gerbrand Bakker It Is Silent Up There erbrand Bakker’s Boven is het stil G4(‘It is silent up there’) is ostensibly a book about the countryside, as seen through the eyes of a farmer, but in the end photo Klaas Koppe it’s about such universal matters as the pos- sibility or impossibility of taking life into Gerbrand Bakker (b. 1962) studied Dutch one’s own hands. language and literature and worked as a It was always the twins, Henk and subtitler for nature films before becoming a Helmer, in that order. When father’s boy, gardener. His previous books include an Henk, died in a car accident, there was no etymological dictionary for children and the way Helmer could continue his studies in juvenile novel Perenbomen bloeien wit (‘Pear Dutch language and literature. He resigned trees bloom white’, 1999), which has been himself to taking over his brother’s role on translated into German. Boven is het stil, his the farm and spending the rest of his days first adult novel, appeared in 2006 and has ‘with his head under a cow’. The announcement ‘I put Father upstairs’ not sold extremely well. The reviews have been only marks the beginning of the novel but also heralds the transformation positive, and the book was awarded the which the main character is to undergo. -

Verses and More: Lola Ridge's Antipodean Poems

ka mate ka ora: a new zealand journal of poetry and poetics Issue 14 July 2016 WAR POEMS for Ka Mate Pekelkist: Some poets’ responses to war. Ricci van Elburg The following poems all refer to the Second World War, specifically as it was experienced in the Netherlands. Brief historical context. At dawn on May 10 1940 German troops invaded the Netherlands from the east in several places. At the same time a large airborne force landed in the western provinces. Their aim was to secure airfields and major bridges over the rivers in the southwest of the country, and to invade the harbour at Rotterdam from the west. After three days of fighting on several local fronts Germany issued an ultimatum on the 14th: surrender or we will bomb Rotterdam like we bombed Guernica and Warsaw. Not stated in those terms of course. While negotiations over details were still being held, the bombers arrived, the centre of Rotterdam was bombed with the result that about 900 people were killed, 25.000 houses were destroyed and fires had started everywhere. Any hesitation about surrendering was cut short by another ultimatum threatening the same treatment for Utrecht, and after that no doubt The Hague and Amsterdam. On May 15 the Netherlands capitulated and became occupied territory, except the southern province of Zeeland, where the French army was for the moment holding its ground. Almost immediately a network of resistance fighters and subversives was started, contacts being made mainly by means of word of mouth or chainmail letters. Part of the ‘small resistance’ was the use of cartoons making fun of the Germans and encouraging civil disobedience. -

Verbal Irony

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/81993 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-02 and may be subject to change. Verbal irony: Use and effects in written discourse een wetenschappelijke proeve op het gebied van de Letteren Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. mr. S.C.J.J. Kortmann, volgens besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 30 september 2010 om 13.30 uur precies door Christian Frederik Burgers geboren op 8 januari 1983 te Nijmegen Promotores: prof. dr. P.J.M.C. Schellens prof. dr. M.J.P. van Mulken Manuscriptcommissie: prof. dr. J.A.L. Hoeken prof. dr. R.N.W.M. van Hout dr. J.M. Sanders prof. dr. G.J. Steen (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam) prof. dr. A. Verhagen (Universiteit Leiden) Printer: Ipskamp Drukkers, Enschede / Nijmegen ISBN: 9789460049996 Cover image: The cover image is a campaign advertisement used by the Conservative Party in the British General Elections of 2010. The advertisement is republished here with permission of the Conservatives. Preface When you turn towards a typical preface in a dissertation, you usually find words of praise of the PhD candidate for many people who helped him or her in preparing the dissertation. After having written a dissertation myself, I can only agree that the process of this research has not been a solitary one. -

Remco Campert: Al Die Dromen Al Die Jaren

Remco Campert: al die dromen al die jaren Samenstelling: Daan Cartens, Aad Meinderts en Erna Staal bron Daan Cartens, Aad Meinderts en Erna Staal, Remco Campert: al die dromen al die jaren (schrijversprentenboek 46). De Bezige Bij Amsterdam / Letterkundig Museum Den Haag 2000 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/cart002remc01_01/colofon.htm © 2006 dbnl / Daan Cartens, Aad Meinderts & Erna Staal i.s.m. 1 Al die dromen al die jaren steeds weer dat kind op 't platgebrande station het hoge gillen in de kazerne waar je stem die mooie vaas werd stukgetrapt. Samenstelling: Daan Cartens, Aad Meinderts en Erna Staal, Remco Campert: al die dromen al die jaren 6 Remco Campert in zijn werkkamer, Amsterdam, december 1999. Foto Chris Pennarts, Montfoort Samenstelling: Daan Cartens, Aad Meinderts en Erna Staal, Remco Campert: al die dromen al die jaren 7 Voorwoord Over de negentiende-eeuwse domineedichter J.J.L. ten Kate, in zijn tijd niet alleen bij het vrome volk immens populair, merkte Cd. Busken Huet eens op dat deze dichtervorst indien men hem van een toren stiet, zou neerkomen aan gruis van verzen. Niemand zal Remco Campert een dergelijke behandeling toewensen, want als er van één schrijver al heel lang, bijna een halve eeuw, veel gehouden wordt, is het van hem. En om uit eigen beweging bijvoorbeeld van de Waalbrug in Nijmegen te stappen, laat staan om als straf voor misplaatste ambities, zoals Icarus destijds, ten val te worden gebracht, daar is hij de man niet naar. Campert is eerder iemand die in beweging gebracht wil worden door wat hij aan menselijk gedoe waarneemt, met inbegrip van dat van hemzelf, dan een man die hemelbestormende acties onderneemt. -

University of Groningen Mediators As the Subject of Dutch Biography the Year in the Netherlands

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Groningen University of Groningen Mediators as the Subject of Dutch Biography Renders, Hans; Veltman, David Published in: Biography; an interdisciplinary quarterly IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2019 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Renders, H., & Veltman, D. (2019). Mediators as the Subject of Dutch Biography: The Year in the Netherlands. Biography; an interdisciplinary quarterly, 42(1), 96-102. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 13-11-2019 Mediators as the Subject of Dutch Biography: The Year in the Netherlands Hans Renders, David Veltman Biography, Volume 42, Number 1, 2019, pp. 96-102 (Article) Published by University of Hawai'i Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/726553 Access provided at 14 Jun 2019 21:26 GMT from University of Groningen Mediators as the Subject of Dutch Biography The Year in the Netherlands Hans Renders and David Veltman On September 18, 2018, the biannual Dutch Biography Prize was awarded to Onno Blom’s biography of the author Jan Wolkers. -

11 Poets from Holland 2 11 Poets from Holland

ederlands N letterenfonds dutch foundation for literature 11 Poets from Holland 2 11 Poets from Holland The Dutch Foundation for Literature / Nederlands Letterenfonds supports writers, translators and Dutch literature in translation Information Travel costs support Dutch Foundation The Foundation’s advisors on poetry, literary The Foundation is able to support a publisher for Literature fiction, quality non-fiction, youth literature and wishing to invite an author for interviews or Nieuwe Prinsengracht 89 1018 VR Amsterdam graphic novels are present each year at promi- public appearances. Literary festivals are Tel. +31 20 520 73 00 nent book fairs, including Frankfurt, London, likewise eligible for support. Additionally, the Fax +31 20 520 73 99 Beijing and Bologna. Poets from Holland, Foundation organizes international literary The Netherlands Books from Holland, Quality Non-Fiction from events in co-operation with local publishers, [email protected] Holland, Children’s Books from Holland and festivals and book fairs. www.letterenfonds.nl Graphic Novelists from Holland recommend Advisor Poetry highlights from each category’s selection. International visitors programme The visitors programme and the annual Individual poets from the Netherlands are also Amsterdam Fellowship offer publishers and featured in separate brochure series: editors the opportunity to acquaint themselves Contemporary Dutch Poets, Zeitgenössische with the publishing business and the literary Niederländische Poesie, and Great Dutch infrastructure of the Netherlands. Poets of the 20th Century. If you would like to receive more information or brochures from this Translators’ House series, please contact Thomas Möhlmann. The Translators’ House offers translators of Thomas Möhlmann [email protected] Dutch literature the opportunity to live and work Over eighty interesting Dutch poets are featured in Amsterdam for a period of time. -

Panorama-Holland-Arabic-2010.Pdf

NLPVF AbuDhabi-10 v10.indd 1 22-02-10 14:02 Singel 464 e [email protected] nl-1017 aw Amsterdam w www.nlpvf.nl t +31(0)20 620 62 61 Bank vsb 86 17 98 066 f +31(0)20 620 71 79 المطبوعات بيت الترجمة كلمة شكر Application form for يسعد المؤسسة الهولندية لدعم اﻹنتاج اﻷدبي إبﻻغ الناشرين اﻻجانب حول نوعية جديدة وناجحة يرحب بيت الترجمة الموجود بامستردام والترجمة أن تقدم شكرها الجزيل الى الوزارة Please fill out this form in capitals and attach a photocopy of your financial support for the من أدب اللغة الهولندية. تنشر المؤسسة 10 كتب بالمترجمين من اللغة الهولندية الى لغة أخرى, الهولندية للتربية والثقافة والعلوم على مساعدتها. .contracts with the copyright holder and with the translator من هولندا والفﻻندر مرتين في السنة وذلك بتعاون ويرغبون من خﻻل ذلك في تحسين مهاراتهم .We would also appreciate a copy of your latest catalogue مع مؤسسة اﻷدب الفلمنكي. اللغوية أو الحفاظ على مستوى معرفتهم بالثقافة Full acknowledgement to the NLPVF for the subsidy must be translation of illustrated إن نوعية الغير الخيالي في هولندا يظهر سنويا الهولندية. يمكن اعتبار بيت الترجمة كقاعدة أساسية printed in the book. For this reason it is important that you apply لمساعدة الناشرين اﻻجانب والمحررين لمواكبة لكل مترجم يأمل في تعميق معرفتة العلمية والذهاب كولفون in good time. children’s books آخر التطورات في نوعية غير الخيال الهولندية. في مشروع الترجمة, فضﻻ عن امكانيات التحدث نشرت المؤسسة الهولندية لدعم اﻹنتاج اﻷدبي Company name هناك منشور سنوي لكتب اﻷطفال في هولندا الذي الى الكتاب اواﻹلتقاء بالناشرين. والترجمة هذا الكتيب بمناسبة مشاركتها في معرض Publisher’s Details يظهر قبل معرض اﻷطفال الدولي للكتاب ببولونيا. -

Remco Campert

Prijs der Nederlandse Letteren Informationen zum autor Autoe Frank Hockx Aantal pagina’s 1 van 12 Remco Campert Zur Biografie Remco Wouter Campert wurde am 28. Juli 1929 in Den Haag als Sohn des Schriftstellers Jan Campert und der Schauspielerin Joekie Broedelet geboren. Drei Jahre nach seiner Geburt trennten sich die Eltern, woraufhin er bis zu seinem zwölften Lebensjahr abwechselnd bei seinem Vater, seiner Mutter und seinen Großeltern lebte. 1941 zog seine Mutter mit ihm nach Amsterdam; ein Jahr später wurde er bei einer Familie in Epe untergebracht. Dort hörte er 1943, dass sein Vater (der Verfasser des in den Niederlanden sehr bekannten Gedichts „De Achttien Dooden“ über die ersten niederländischen Widerstandskämpfer) im Konzentrationslager Neuengamme gestorben war. 2005 wurde Campert mit dem Bericht konfrontiert, dass die Todesursache seines Vaters nicht Erschöpfung gewesen sei. Stattdessen sei er von Mitgefangenen ermordet worden, da er einige Schicksalsgenossen bei der Lagerleitung verraten habe. Eine nähere Untersuchung konnte die Beschuldigung entkräften und zeichnete das Bild eines Jan Campert, der zwar – um Geld zu verdienen – Artikel für pro-deutsche Blättern geschrieben hatte, der jedoch auch im Widerstand aktiv war. Nach dem Krieg, im September 1945, kehrten Remco Campert und seine Mutter wieder nach Amsterdam zurück, wo er das Gymnasium besuchte. In der Schulzeitung hatte er eine eigene Rubrik und lieferte zudem einen Comicstrip. Im Laufe der Jahre ließ er sich jedoch immer weniger in der Schule blicken. Er verbrachte seine Zeit im Kino (wo er sich zuweilen vier Filme am Tag anschaute), in Jazzclubs und Kneipen. Nach dem großen Entschluss, Schriftsteller zu werden, ging er verfrüht von der Schule ab. -

University of Groningen Mediators As the Subject of Dutch Biography the Year in the Netherlands

University of Groningen Mediators as the Subject of Dutch Biography Renders, Hans; Veltman, David Published in: Biography; an interdisciplinary quarterly DOI: 10.1353/bio.2019.0015 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2019 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Renders, H., & Veltman, D. (2019). Mediators as the Subject of Dutch Biography: The Year in the Netherlands. Biography; an interdisciplinary quarterly, 42(1), 96-102. https://doi.org/10.1353/bio.2019.0015 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. -

Nederlandse & Vertaalde Fictie

nederlandse & vertaalde fictie | non-fictie 24 Nir Baram, Aan het einde van de nacht 66 John Barton, De Bijbel 6 Kees van Beijnum, 23 seconden 2 Onno Blom, De jonge Rembrandt 36 Daan Borrel, Jaar van het nieuwe verhaal 50 Pieter Boskma, Van de zoon en de zee 90 Jan Caeyers, Beethoven 70 Remco Campert, Katten en Katers 10 Roberto Camurri, De menselijke maat 28 Bart Chabot, mijn vaders hand 102 Paolo Cognetti, De acht bergen (mp) 88 Rachel Cusk, Coventry 80 J.A. Deelder, Hardgin 32 Mohamed El Bachiri met David Van Reybrouck, De odyssee van Mohamed 72 Urs Faes, Tijd tussen de jaren 76 Jean Genet, Dagboek van een dief 64 Alicja Gescinska, Intussen komen mensen om 103 Paolo Giordano, De hemel verslinden (mp) 20 Elisa Hermanides & Ruben Koops, Ahmed Aboutaleb 98 Willem Frederik Hermans, Volledige Werken 19 52 Delphine Lecompte, Vrolijke verwoesting 38 Ron Meerhof, Opstelten 54 Jens Meijen, Xenomorf 92 Daniel Mendelsohn, Pijn en genot 82 Edna O’Brien, Meisje 74 Shane O’Mara, Lopen 16 Ann Patchett, Het Hollandse huis 56 Hagar Peeters, De schrijver is een alleenstaande moeder 86 Willem Schinkel, Politieke stenogrammen 92 W.G. Sebald, Austerlitz, Duizelingen, De ringen van Saturnus en De emigrés 42 Marten Toonder, Het geheim van Marten Toonder 58 Peter Verhelst, Zon 60 Timur Vermes, De hongerigen en de verzadigden 78 Lawrence Weschler, En hoe gaat het met u, dokter Sacks? 48 Tommy Wieringa, De heilige Rita (mp) 14 Tommy Wieringa, Onmetelijke liefde 100 Jan Wolkers, Amstelglorie en Het litteken van de dood In De jonge Rembrandt laat de veelgeprezen biograaf Onno Blom zien hoe Rembrandt in het vroegzeventiende-eeuwse Leiden tot wasdom kwam – en vertelt zo het prachtige verhaal van een stad en haar beroemdste zoon. -

Boekenweek: Schrijversvrienden ••• Interview Met Tom Lanoye •••

lezen1-2012:Opmaak 1 16-02-2012 23:19 Page 3 J A A R G A N G 7 N U M M E R 1 2 0 1 2 E E N U I T G A V E V A N S T I C H T I N G L E Z E N PRENTENBOEKENMAKERS GAAN DIGITAAL BOEKENWEEK: SCHRIJVERSVRIENDEN ••• INTERVIEW MET TOM LANOYE ••• DIGITALE PRENTENBOEKEN ••• DE OPMARS VAN HET TOEGANKELIJKE KINDER- BOEK ••• FLOORTJE ZWIGTMAN ONTMOET MEG ROSOFF ••• LEESGEDRAG BOVEN- BOUWSCHOLIEREN ••• KINDERBOEKENSCHRIJVERS VOOR VOLWASSENEN ••• SCHOOLBIBLIOTHEKEN ••• EEN KIJKJE IN HET ATELIER VAN ALEX DE WOLF lezen1-2012:Opmaak 1 16-02-2012 23:19 Page 4 A G E N D A 8 maart Bekendmaking longlist Dioraphte Jongeren- 14 april Nationale Leesvertelwedstrijd voor dove 23 mei Slotmanifestatie VERS, www.versgedicht.nl literatuur Prijs, www.jongerenliteratuurprijs.org kinderen, www.fodok.nl 31 mei Uitreiking Gouden Strop, 12 maart Uitreiking De Inktaap, www.inktaap.nl 19 april Uitreiking Dioraphte Jongerenliteratuur Prijs, www.degoudenstrop.nl 14-24 maart Boekenweek, thema: ‘Vriendschap en www.jongerenliteratuurprijs.org juni Maand van het Spannende Boek, andere ongemakken’, www.boekenweek.nl 22 april Finale Kinderen en Poëzie, www.maandvanhetspannendeboek.nl 14-24 maart Week van het Christelijke boek, www.poeziepaleis.nl juni Uitreiking C. Buddingh’ prijs voor nieuwe Neder- www.bcbplein.nl 23-28 april Week van het luisterboek, landstalige poëzie, www.poetry.nl 20 maart Lezen Centraal, lezen in het vmbo, www.weekvanhetluisterboek.nl 2 juni Finale landelijke dichtwedstrijd Doe Maar wat maakt het verschil? www.lezencentraal.nl half mei Bekendmaking Prentenboek van het jaar, Dicht Maar, www.poeziepaleis.nl 21 maart Boekenweek Live! 2012, www.denationalevoorleesdagen.nl 6 juni Bekendmaking winnaar Nederlandse Kinderjury, www.boekenweek.nl 7 mei Uitreiking Libris Literatuurprijs, www.kinderjury.nl 28 maart Bekendmaking shortlist Dioraphte Jongeren- www.librisliteratuurprijs.nl 11 juni Bekendmaking Zilveren Griffels literatuur Prijs, www.jongerenliteratuurprijs.org 9-20 mei Annie M.G.