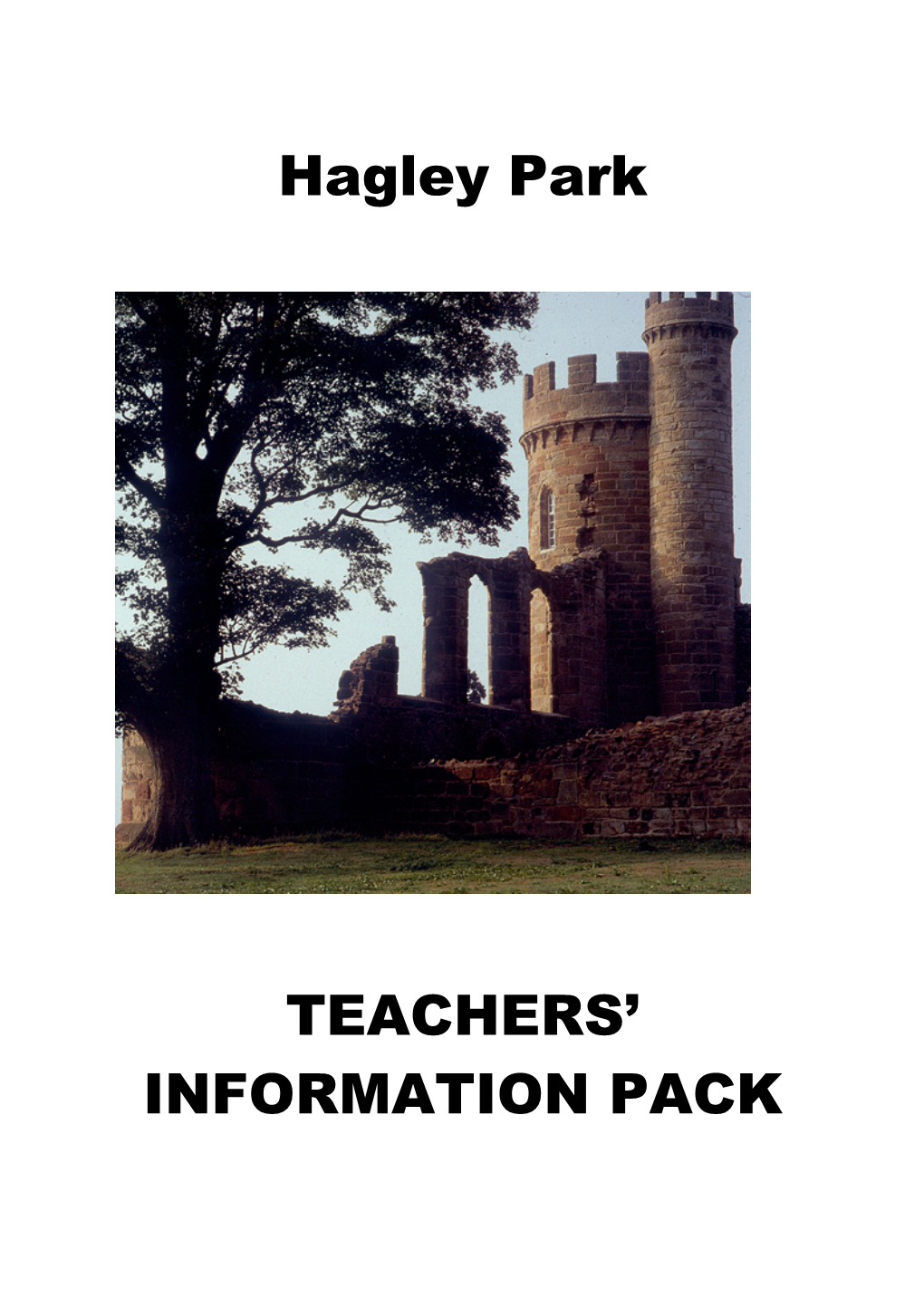

Hagley Park TEACHERS' INFORMATION PACK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Country Urban Park Barometer

3333333 Black Country Urban Park Barometer April 2013 DRAFT WORK IN PROGRESS Welcome to the Black Country Urban Park Barometer. Transformation of the Environmental Infrastructure is one of the key to drivers identified in the Black Country Strategy for Growth and Competitiveness. The full report looks at the six themes created under the ‘Urban Park’ theme and provides a spatial picture of that theme accompanied with the key assets and opportunities for that theme. Foreword to be provided by Roger Lawrence The Strategic Context Quality of the Black Country environment is one of the four primary objectives of the Black Country Vision that has driven the preparation of the Black Country Strategy for Growth and Competitiveness through the Black Country Study process. The environment is critical to the health and well-being of future residents, workers and visitors to the Black Country. It is also both a major contributor to, and measure of, wider goals for sustainable development and living as well as being significantly important to the economy of the region. The importance and the desire for transforming the Black Country environment has been reinforced through the evidence gathering and analysis of the Black Country Study process as both an aspiration in its own right and as a necessity to achieve economic prosperity. Evidence from the Economic and Housing Studies concluded that ‘the creation of new environments will be crucial for attracting investment from high value-added firms’ and similarly that ‘a high quality healthy environment is a priority for ‘knowledge workers’. The Economic Strategy puts ‘Environmental Transformation’ alongside Education & Skills as the fundamental driver to achieve Black Country economic renaissance and prosperity for its people. -

Things to Do and Places to Go Sept 2020

Things To Do And Places to Go! September 2020 Table of Contents Parks and Nature Reserves ............................................................................................... 3 Arrow Valley Country Park ....................................................................................................... 3 Clent Hills ................................................................................................................................ 3 Cofton Park .............................................................................................................................. 3 Cannon Hill Park ...................................................................................................................... 3 Highbury Park .......................................................................................................................... 3 King’s Heath Park ..................................................................................................................... 4 Lickey Hills ............................................................................................................................... 4 Manor Farm ............................................................................................................................. 4 Martineau Gardens .................................................................................................................. 4 Morton Stanley Park ............................................................................................................... -

The Wedding Brochure

A wedding lasts a day... ...memories last a life time “We would definitely Set in 350 acres of stunning landscaped parkland with spectacular views. recommend the venue for a perfect Hagley Hall with its rich Rococo décor offers a truly splendid and unique wedding” venue for your wedding day. Jude & Julian St John the Baptist Hagley If you are thinking of a church wedding why not consider St John’s church which is located in the grounds of Hagley Hall. Weddings at St John’s are very popular because of the beautiful setting with excellent car parking for your guests. We offer • A Church of England wedding service tailored to your needs • Help with your choice of hymns It may well be possible for you to be • Help with your choice of readings married at St John’s even • A church choir if you live outside the Hagley Parish. • If you wish your family or friends could read or sing a solo • Ringing of the church bells before and after the wedding We look forward to hearing from you. service • Experienced church wardens who can help you on the day In the first instance please contact the • An invite to our annual March “wedding tea” parish office on 01562 886363 or • Two wedding preparation sessions with the Rector email [email protected] • An informal rehearsal opportunity prior to your wedding day • Current costs run from £648 through to £950 - these You can also take a look at our web site: being dependant on your individual needs www.hagleycofe.co.uk The White Hall Enjoy champagne and canapés in the White Hall, with its wonderful arched lobby and scagliola figures of the gods Bacchus, Mercury and Venus. -

Notice of Poll Bromsgrove 2021

NOTICE OF POLL Bromsgrove District Council Election of a County Councillor for Alvechurch Electoral Division Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a County Councillor for Alvechurch Electoral Division will be held on Thursday 6 May 2021, between the hours of 07:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of County Councillors to be elected is one. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Assentors BAILES 397 Birmingham Road, Independent Kilbride Karen M(+) Van Der Plank Alan Bordesley, Redditch, Kathryn(++) Worcestershire, B97 6RH LUCKMAN 40 Mearse Lane, Barnt The Conservative Party Woolridge Henry W(+) Bromage Daniel P(++) Aled Rhys Green, B45 8HL Candidate NICHOLLS 3 Waseley Road, Labour Party Hemingway Oreilly Brett A(++) Simon John Rubery, B45 9TH John L F(+) WHITE (Address in Green Party Ball John R(+) Morgan Kerry A(++) Kevin Bromsgrove) 4. The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Station Ranges of electoral register numbers of Situation of Polling Station Number persons entitled to vote thereat Rowney Green Peace Mem. Hall, Rowney Green Lane, Rowney 1 ALA-1 to ALA-752 Green Beoley Village Hall, Holt End, Beoley 2 ALB-1 to ALB-809 Alvechurch Baptist Church, Red Lion Street, Alvechurch 3 ALC-1 to ALC-756 Alvechurch -

Wider. Bigger. Greater

WIDER. BIGGER. GREATER. Neo-Palladian Country Houses as Representations of Power Struggle, Globalization and “Britishness” in the United Kingdom of the 1750s Stefanie Leitner s1782088 - [email protected] Supervisor: Dr. J.G. Roding Second reader: Dr. E. den Hartog MA Arts and Culture 2016/2017 Specialization: Architecture TABLE OF CONTENT 1. Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Theoretical Framework ......................................................................... 2 1.2. Literature Review ................................................................................. 4 2. Node I – Architecture .................................................................................. 8 2.1. General developments compared to the 1720s .................................... 8 2.2. Introduction of the Case Studies .......................................................... 9 2.2.1. Holkham Hall (1734-1764) ........................................................... 11 2.2.2. Hagley Hall (1754-1760)............................................................... 20 2.2.3. Kedleston Hall (1759) ................................................................... 28 3. Node II – Globalization ............................................................................. 38 3.1. Colonization and the British Empire ................................................. 38 3.2. Connection with continental Europe .................................................. 39 3.3. -

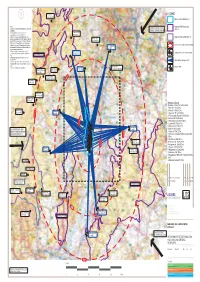

L02-2135-02B-Intervisibilty B

LEGEND Pole Bank 516m AOD (NT) Malvern Hills AONB (Note 3) Notes: Adjacent AONB boundaries LONGER DISTANCE VIEWS 1. Base taken from A-Z Road Maps for Birmingham (Note 3) and Bristol FROM BEYOND BIRMINGHAM 2. Viewpoints have been selected to be Brown Clee Hill representative, and are not definitive 540m AOD 3. Taken from www.shropshirehillsaonb.co.uk Adjacent National Park (Note 7) website, www.cotswoldaonb.com website, Malvern Kinver Edge Hills District Council Local Plan Adopted 12th July 155m AOD (NT) 2006, Forest of Dean District Local Plan Review 30km Distance from spine of Malvern Hills Adopted November 2005, Herefordshire Unitary Clent Hills 280m Development Plan Adopted 23rd March 2007 and AOD (NT) wyevalleyaonb.org.uk website 4. Observer may not nessecarily see all of Titterstone Clee 10 intervening land between viewpoint and Malvern 1 Viewpoint used as visual receptor SHROPSHIRE AONB Hill 500m AOD Hills 14 5. Information obtained from the Malvern Hill Conservators Intervisibility viewing corridor 6. Views outside inner 15km study area graded on Appendix Table 1, but not shown graded on plan L02. M5 alongside 7. Taken from OS Explorer MapOL13. Clows Top Malvern Hills High Vinnals 11 Bromsgrove 100m AOD Harley’s Mountain 231m AOD A 370m AOD 50km 386m AOD Bircher Common 160-280m AOD (NT) Hawthorn Hill 30km 407m AOD Bradnor Hill 391m AOD (NT) Hergest Ridge 426m AOD Malvern Hills (Note 4) 22 peaks including from north to south: A-End Hill 1079ft (329m) 41 Glascwn Hill Westhope B-North Hill 1303ft (397m) 522m AOD Hill 120m C-Sugarloaf -

Hagley & Blakedown Domestic Service

HAGLEY HISTORICAL AND FIELD SOCIETY NO 4 IN A SERIES OF OCCASIONAL PAPERS HAGLEY & BLAKEDOWN IN TI{E 19TTI CENTURY DOMESTIC SERVICE ND SOCIAL BACKGROTIND This Hagley Historical & Field Society Occasional Paper No 4 is the third of the series to use the Census Returns of 1851 and 1881 as source material. Occasional Paper No 1 showed the number of incomers' into Hagley and Blakedown (then part of Hagley) and the consequent increase in new housing. Occasional Paper No 3 dealt with occupations, particularly the workforce in agriculture. industry, crafts/trades and services. The growing number of moneyed inhabitants was noted, especially in Upper Hagley. , Occasional Paper No 4 now closely investigates the large category of Domestic Servants. Family size is also examined, together with Schools, the Churches, and Leisure which formed the social background. As in Occasional Paper No 3, the parish is divided into two sections corresponding with the two Enumeration Districts adopted in the Census Return of l88l . i. e. Enumeration District No 2 (ED2) which included both sides of the Stourbridge Road to what is now thre crossroads, tfre east side of the present Bromsgrove Road to Hall Lane opposite the Lyttelton Arms corner, what is now Hall Lane, Hall Drive, Hagley Hall, the Castle, Birmingham Road/School Lane area, Hagley Hill, Broadmarsh and Wassell Grove, and Enumeration District No 3 (ED3)) which included the west side of Bromsgrove Road to the @,Middlefoot(nowMiddlefield)Lane,LowerHagley,TheBrake' The Birches, Stakenbridge, and Blakedown. In the following text Enumeration District No 2 will be referred to as ED2 and Enurneration District No 3 as ED3. -

Vebraalto.Com

The Guildford Wychbury Fields Hagley DY9 0QF Price £499,950 In a picturesque setting at the foot of Clent Hills, our exclusive Wychbury Fields development of two, three, four and five bedroom homes enjoy an open outlook, with some offering views towards the Malvern Hills. Generous in space and scope, as well as boasting high specification throughout, these light and airy homes benefit from a wealth of local amenities and respected schools. While the commuting and entertaining appeal of Birmingham is only a short 15-mile drive away. Commuting from this desirable semi-rural retreat is just as convenient. Whether the office, family or school run calls, you can be there in next to no time, with access to Junction 3 of the M5 located about six miles away from Hagley taking you straight to the city centre. Or you can take advantage of the direct trains from Hagley station to Birmingham Moor Street in around 34 minutes, as well as to Worcester, Solihull and Cheltenham. Regular buses also run to Stourbridge via A491 and Kidderminster on the A456. The sought-after village of Hagley can be found just to the south of Stourbridge on the Worcestershire border. An affluent and leafy residential suburb, it’s also home to a lovely choice of independent shops, country pubs and fashionable eateries. Famous for glass production, Stourbridge offers a wealth of banks, high street stores and supermarkets including Waitrose, together with popular bars and restaurants. While Merry Hill Shopping Centre in Dudley is about seven miles away and the city buzz of Birmingham is a little further. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOURTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 . 737-4215/842-6353 EXHBITION FACT SHEET Title; THE TREASURE HOUSES OF BRITAIN: FIVE HUNDRED YEARS OF PRIVATE PATRONAGE AND ART COLLECTING Patrons: Their Royal Highnesses The Prince and Princess of Wales Dates; November 3, 1985 through March 16, 1986, exactly one week later than previously announced. (This exhibition will not travel. Loans from houses open to view are expected to remain in place until the late summer of 1985 and to be returned before many of the houses open for their visitors in the spring of 1986.) Credits; This exhibition is made possible by a generous grant from the Ford Motor Company. The exhibition was organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, in collaboration v\n.th the British Council and is supported by indemnities from Her Majesty's Treasury and the U.S. Federal Council on the Arts and Humanities. Further British assistance was supplied by the National Trust and the Historic Houses Association. History of the exhibition; The suggestion that the National Gallery of Art consider holding a major exhibition devoted to British art was made by the British Council in 1979. J. Carter Brown, Director of the National Gallery, responded with the idea of an exhibition on the British Country House as a "vessel of civilization," bringing together works of art illustrating the extraordinary achievement of collecting and patronage throughout Britain over the past five hundred years. As this concept carried with it the additional, contemporary advantage of stimulating greater interest in and support of those houses open to public viewing, it was enthusiastically endorsed by the late Lord Howard of Henderskelfe, then-Chairman of the Historic Houses Association, Julian Andrews, Director of the Fine Arts Department of the British Council, and Lord Gibson, Chairman of the National Trust. -

Application Dossier for the Proposed Black Country Global Geopark

Application Dossier For the Proposed Black Country Global Geopark Page 7 Application Dossier For the Proposed Black Country Global Geopark A5 Application contact person The application contact person is Graham Worton. He can be contacted at the address given below. Dudley Museum and Art Gallery Telephone ; 0044 (0) 1384 815575 St James Road Fax; 0044 (0) 1384 815576 Dudley West Midlands Email; [email protected] England DY1 1HP Web Presence http://www.dudley.gov.uk/see-and-do/museums/dudley-museum-art-gallery/ http://www.blackcountrygeopark.org.uk/ and http://geologymatters.org.uk/ B. Geological Heritage B1 General geological description of the proposed Geopark The Black Country is situated in the centre of England adjacent to the city of Birmingham in the West Midlands (Figure. 1 page 2) .The current proposed geopark headquarters is Dudley Museum and Art Gallery which has the office of the geopark coordinator and hosts spectacular geological collections of local fossils. The geological galleries were opened by Charles Lapworth (founder of the Ordovician System) in 1912 and the museum carries out annual programmes of geological activities, exhibitions and events (see accompanying supporting information disc for additional detail). The museum now hosts a Black Country Geopark Project information point where the latest information about activities in the geopark area and information to support a visit to the geopark can be found. Figure. 7 A view across Stone Street Square Dudley to the Geopark Headquarters at Dudley Museum and Art Gallery For its size, the Black Country has some of the most diverse geology anywhere in the world. -

Guide to Resources in the Archive Self Service Area

Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service www.worcestershire.gov.uk/waas Guide to Resources in the Archive Self Service Area 1 Contents 1. Introduction to the resources in the Self Service Area .............................................................. 3 2. Table of Resources ........................................................................................................................ 4 3. 'See Under' List ............................................................................................................................. 23 4. Glossary of Terms ........................................................................................................................ 33 2 1. Introduction to the resources in the Self Service Area The following is a guide to the types of records we hold and the areas we may cover within the Self Service Area of the Worcestershire Archive and Archaeology Service. The Self Service Area has the same opening hours as the Hive: 8.30am to 10pm 7 days a week. You are welcome to browse and use these resources during these times, and an additional guide called 'Guide to the Self Service Archive Area' has been developed to help. This is available in the area or on our website free of charge, but if you would like to purchase your own copy of our guides please speak to a member of staff or see our website for our current contact details. If you feel you would like support to use the area you can book on to one of our workshops 'First Steps in Family History' or 'First Steps in Local History'. For more information on these sessions, and others that we hold, please pick up a leaflet or see our Events Guide at www.worcestershire.gov.uk/waas. About the Guide This guide is aimed as a very general overview and is not intended to be an exhaustive list of resources. -

Landscape Value Study Report June 2019 CPRE Worcestershire

Clent & Lickey Hills Landscape Value Study Report June 2019 CPRE Worcestershire Clent and Lickey Hills Area Landscape Value Study June 2019 Prepared by Carly Tinkler CMLI and CFP for CPRE Worcestershire Clent & Lickey Hills Landscape Value Study Report June 2019 CPRE Worcestershire Clent and Lickey Hills Area Landscape Value Study Technical Report Prepared for CPRE Worcestershire June 2019 Carly Tinkler BA CMLI FRSA MIALE Community First Partnership Landscape, Environmental and Colour Consultancy The Coach House 46 Jamaica Road Malvern 143-145 Worcester Road WR14 1TU Hagley, Worcestershire [email protected] DY9 0NW 07711 538854 [email protected] 01562 887884 Clent & Lickey Hills Landscape Value Study Report June 2019 CPRE Worcestershire Document Version Control Version Date Author Comment Draft V1 14.06.2019 CL / CT Issued to CPREW for comment Draft V1 02.07.2019 CL / CT Minor edits Final 08.07.2019 CL / CT Final version issued to CPREW for publication Clent & Lickey Hills Landscape Value Study Report June 2019 CPRE Worcestershire Contents Page number Acronyms 1 Introduction 1 2 Landscape Value 4 3 Method, Process and Approach 15 4 Landscape Baseline 21 5 Landscape Value Study Results 81 6 Conclusions and Recommendations 116 Appendices Appendix A: Figures Appendix B: Landscape Value Study Criteria Figures Figure 1: Study Area Figure 2: Landscape Value Study Zones Figure 3: Former Landscape Protection Areas Figure 4: Landscape Baseline - NCAs and LCTs Figure 5: Landscape Baseline - Physical Environment Figure 6: Landscape Baseline - Heritage Figure 7: Landscape Baseline - Historic Landscape Character Figure 8: Landscape Baseline - Biodiversity Figure 9: Landscape Baseline - Recreation and Access Figure 10: Key Features - Hotspots Figure 11: Valued Landscape Areas All Ordnance Survey mapping used in this report is © Ordnance Survey Crown 2019.