RCEWA Case Xx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sara Fox [email protected] Tel +1 212 636 2680

For Immediate Release May 18, 2012 Contact: Sara Fox [email protected] tel +1 212 636 2680 A MASTERPIECE BY ROMANINO, A REDISCOVERED RUBENS, AND A PAIR OF HUBERT ROBERT PAINTINGS LEAD CHRISTIE’S OLD MASTER PAINTINGS SALE, JUNE 6 Sale Includes Several Stunning Works From Museum Collections, Sold To Benefit Acquisitions Funds GIROLAMO ROMANINO (Brescia 1484/87-1560) Christ Carrying the Cross Estimate: $2,500,000-3,500,000 New York — Christie’s is pleased to announce its summer sale in New York of Old Master Paintings on June 6, 2012, at 5 pm, which primarily consists of works from private collections and institutions that are fresh to the market. The star lot is the 16th-century masterpiece of the Italian High Renaissance, Christ Carrying the Cross (estimate: $2,500,000-3,500,000) by Girolamo Romanino; see separate press release. With nearly 100 works by great French, Italian, Flemish, Dutch and British masters of the 15th through the 19th centuries, the sale includes works by Sir Peter Paul Rubens, Hubert Robert, Jan Breughel I, and his brother Pieter Brueghel II, among others. The auction is expected to achieve in excess of $10 million. 1 The sale is highlighted by several important paintings long hidden away in private collections, such as an oil-on-panel sketch for The Adoration of the Magi (pictured right; estimate: $500,000 - $1,000,000), by Sir Peter Paul Rubens (Siegen, Westphalia 1577- 1640 Antwerp). This unpublished panel comes fresh to market from a private Virginia collection, where it had been in one family for three generations. -

Former Wye College, Wye (Wye 3) DRAFT

Former Wye College, Wye (Wye 3) DRAFT Masterplan Consultation Draft March 2018 Prepared on behalf of Telereal Trillium This document has been designed to be printed double sided at A3 (landscape). Church Barn Milton Manor Farm Canterbury Kent. CT4 7PP 01227 456699 www.bdb-design.co.uk [email protected] Former Wye College,Wye (Wye 3) CONTENTS March 2018 01 Introduction Appendices 02 Background a. Extract from Wye Village Design Statement 03 The Design Process b. Planning Policies and Guidance c. Indicative Walking Distance Radius Map 04 Summary of Relevant Planning Policy 05 Stakeholder Consultation 06 Constraints and Opportunities and Planning and Design Principles 07 Heritage and Townscape Context 08 Detailed Site Appraisals 09 Landscape Strategy 10 Urban Design Vision 11 Framework Strategy and Options and Design Evolution 12 Summary of Key Conclusions of Transport Study 13 Summary of Key Conclusions of Drainage Study 14 Masterplan Proposals 15 Implementation FORMER WYE COLLEGE, WYE (WYE 3) : MASTERPLAN INTRODUCTION 01 Project Brief This Masterplan has been prepared to guide the future change of use and redevelopment of the former Wye College Campus at Wye, as shown on the plan on the right. This Masterplan has been prepared in the context of the policies of the Wye Neighbourhood Development Plan 2015–2030, adopted in October 2016; Policy WNP6, mixed development, of the Neighbourhood Plan indicates that development proposals for the Wye 3 site (the planning policy designation for the site in the adopted Tenterden and Rural Sites DPD) should deliver a mix of uses, including education, business, community infrastructure and summer housing, given the scale of the site in relation to the village, such development should be developed in a phased manner in accordance with the Masterplan that has been adopted as a Supplementary Planning Document by Ashford Borough Council. -

November 2012 Newsletter

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 29, No. 2 November 2012 Jan and/or Hubert van Eyck, The Three Marys at the Tomb, c. 1425-1435. Oil on panel. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. In the exhibition “De weg naar Van Eyck,” Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, October 13, 2012 – February 10, 2013. HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President - Stephanie Dickey (2009–2013) Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art Queen’s University Kingston ON K7L 3N6 Canada Vice-President - Amy Golahny (2009–2013) Lycoming College Williamsport, PA 17701 Treasurer - Rebecca Brienen University of Miami Art & Art History Department PO Box 248106 Coral Gables FL 33124-2618 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Contents Board Members President's Message .............................................................. 1 Paul Crenshaw (2012-2016) HNA News ............................................................................1 Wayne Franits (2009-2013) Personalia ............................................................................... 2 Martha Hollander (2012-2016) Exhibitions ............................................................................ 3 Henry Luttikhuizen (2009 and 2010-2014) -

Networking in High Society the Duarte Family in Seventeenth-Century Antwerp1

Networking in high society The Duarte family in seventeenth-century Antwerp1 Timothy De Paepe Vleeshuis Museum | Klank van de stad & University of Antwerp At the end of the sixteenth century the Duarte family, who were of Jewish origin, moved from Portugal to Antwerp and it was here that Diego (I) Duarte laid the foundations for a particularly lucrative business in gemstones and jewellery. His son Gaspar (I) and grandson Gaspar (II) were also very successful professionally and became purveyors of fine jewellery to the courts in (among other places) England, France, the Dutch Republic and the Habsburg Empire. Their wealth enabled the Duartes to collect art and make music in their “palace” on the Meir. Their artistic taste and discernment was such that the mansion became a magnet for visitors from all over Western Europe. The arts were a catalyst for the Duartes’ business, but also constituted a universal language that permitted the family to transcend religious and geographical borders. The death of Diego (II) Duarte in 1691 brought to an end the story of the Duartes in Antwerp. The Duartes were possibly the foremost dealers in jewellery and gemstones in Antwerp in the seventeenth century, but they did not achieve that position without a great deal of effort. Thanks to hard work, determination, a love of the arts and a widespread family network, plus the advantage of Antwerp’s geographically central position, these enterprising cosmopolitans managed to overcome religious discrimination and a succession of setbacks. And in the intimacy of their home they brought together the world of business, the arts and diplomacy in an environment that welcomed every discerning visitor, irrespective of his or her religious background. -

C170 Revolution.Pdf

Lot 1 The 1st Gun ever issued to the America Army Brought to America by Lafayette and marked ‘US’ by order of Gen. Washington One of Finest “US” marked Charleville’s in Existence French import “Charleville’ 1766 musket surcharged ‘US’, weapons negotiated by Benjamin Franklin, Silas Deane and Arthur Lee - France became America’s 1st Ally in the war for Independence from England and the Marquis de Lafayette personally delivered the first 200 guns upon his arrival, followed by ship loads of French weapons and soldiers that turned the tide of battle and enabled the Americans to defeat the British Army, as most of Washington’s Army carried these French guns, only a few are known to exist in this Superb condition and marked “US” the 1st gun of the American Army and the gun that won the War. Ex: Don Bryan $27,500 Lot 3 The Earliest American Powder Horn and certainly the Finest in Existence 1730’s depicting Cherokee Indians in Georgia Post Queen Anne War Powder Horn depicting Cherokee Indians as British Allies in Georgia, scalping a settler, gunstock war club, carrying the British Flag, Scotsman with sword. Amazing detail images and magnificently rococo carved powder horn by a master carver depicting his adventures in the southern most outpost in the Brit- Lot 2 King Charles II – 1683 Gold Gilt Indian Peace Medal from the Ford Collection ish Colonies in North America, most notably the Cherokee Warriors depicting their weapons and “Cut-Ears”. Scotsmen where the first and only traders amongst the The King Charles II Royal Medal of Distinction presented to Native American Leaders and others throughout the British Empire. -

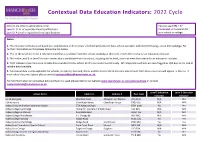

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

County Index, Hosts' Index, and Proposed Progresses

County Index of Visits by the Queen. Hosts’ Index: p.56. Proposed Progresses: p.68. Alleged and Traditional Visits: p.101. Mistaken visits: chronological list: p.103-106. County Index of Visits by the Queen. ‘Proposed progresses’: the section following this Index and Hosts’ Index. Other references are to the main Text. Counties are as they were in Elizabeth’s reign, disregarding later changes. (Knighted): knighted during the Queen’s visit. Proposed visits are in italics. Bedfordshire. Bletsoe: 1566 July 17/20: proposed: Oliver 1st Lord St John. 1578: ‘Proposed progresses’ (letter): Lord St John. Dunstable: 1562: ‘Proposed progresses’. At The Red Lion; owned by Edward Wyngate; inn-keeper Richard Amias: 1568 Aug 9-10; 1572 July 28-29. Eaton Socon, at Bushmead: 1566 July 17/20: proposed: William Gery. Holcot: 1575 June 16/17: dinner: Richard Chernock. Houghton Conquest, at Dame Ellensbury Park (royal): 1570 Aug 21/24: dinner, hunt. Luton: 1575 June 15: dinner: George Rotherham. Northill, via: 1566 July 16. Ridgmont, at Segenhoe: visits to Peter Grey. 1570 Aug 21/24: dinner, hunt. 1575 June 16/17: dinner. Toddington: visits to Henry Cheney. 1564 Sept 4-7 (knighted). 1570 Aug 16-25: now Sir Henry Cheney. (Became Lord Cheney in 1572). 1575 June 15-17: now Lord Cheney. Willington: 1566 July 16-20: John Gostwick. Woburn: owned by Francis Russell, 2nd Earl of Bedford. 1568: ‘Proposed progresses’. 1572 July 29-Aug 1. 1 Berkshire. Aldermaston: 1568 Sept 13-14: William Forster; died 1574. 1572: ‘Proposed progresses’. Visits to Humphrey Forster (son); died 1605. 1592 Aug 19-23 (knighted). -

Caravaggio, Second Revised Edition

CARAVAGGIO second revised edition John T. Spike with the assistance of Michèle K. Spike cd-rom catalogue Note to the Reader 2 Abbreviations 3 How to Use this CD-ROM 3 Autograph Works 6 Other Works Attributed 412 Lost Works 452 Bibliography 510 Exhibition Catalogues 607 Copyright Notice 624 abbeville press publishers new york london Note to the Reader This CD-ROM contains searchable catalogues of all of the known paintings of Caravaggio, including attributed and lost works. In the autograph works are included all paintings which on documentary or stylistic evidence appear to be by, or partly by, the hand of Caravaggio. The attributed works include all paintings that have been associated with Caravaggio’s name in critical writings but which, in the opinion of the present writer, cannot be fully accepted as his, and those of uncertain attribution which he has not been able to examine personally. Some works listed here as copies are regarded as autograph by other authorities. Lost works, whose catalogue numbers are preceded by “L,” are paintings whose current whereabouts are unknown which are ascribed to Caravaggio in seventeenth-century documents, inventories, and in other sources. The catalogue of lost works describes a wide variety of material, including paintings considered copies of lost originals. Entries for untraced paintings include the city where they were identified in either a seventeenth-century source or inventory (“Inv.”). Most of the inventories have been published in the Getty Provenance Index, Los Angeles. Provenance, documents and sources, inventories and selective bibliographies are provided for the paintings by, after, and attributed to Caravaggio. -

RCEWA Case Xx

Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest, note of case hearing on 15 January 2014: A Portrait of Everhard Jabach and family by Charles Le Brun (Case 23, 2013-14) Application 1. The Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest (RCEWA) met on 15 January 2014 to consider an application to export A Portrait of Everhard Jabach and family, by Charles Le Brun. The value shown on the export licence application was £7,300,000 which represented the price agreed through a private sale, subject to the granting of an export licence. The expert adviser had objected to the export of the portrait under the second and third Waverley criteria, on the grounds that it was of outstanding aesthetic importance; and that it was of outstanding significance for the study of group portraiture in Europe in the 17th century. 2. The eight regular RCEWA members present were joined by three independent assessors, acting as temporary members of the Reviewing Committee. 3. The applicant confirmed that the owner understood the circumstances under which an export licence might be refused and that, if the decision on the licence was deferred, the owner would allow the picture to be displayed for fundraising. Expert’s submission 4. The expert adviser had provided a written submission stating that the Portrait of Everhard Jabach and family, by Charles Le Brun was a masterpiece of group portraiture. Everhard Jabach, a wealthy banker from Cologne, had settled in Paris in 1638 and become Cardinal Mazarin’s banker in 1642. -

Romanticism and the Portrait

Diploma Lecture Series 2013 Revolution to Romanticism: European Art and Culture 1750-1850 Romanticism and the portrait Dr Christopher Allen 23/24 October 2013 Lecture summary: It would be tempting, but facile, to contrast the spontaneity, energy and individuality of the Romantic portrait with the artificiality and formality of earlier ones. In reality portraits have reflected or embodied complex and subtle ideas of what makes an individual from the time of the rediscovery of the art in the Renaissance. But how portraits are painted changes in step with evolving conceptions of what constitutes our character, of how character relates to social role, and how individuals interact with their fellows. In other words, an understanding of the history of portraiture really requires some appreciation of the physiological, psychological, epistemological and even political beliefs of the relevant periods. Thus Renaissance portraiture rests fundamentally on the humoral theory of physiology and psychology, eighteenth century portraits reflect the interest in empiricist psychology, and romantic portraits embody a new sense of the individual as a dynamic and often solitary agent in the worlds of nature and of human history. Slide list: Hyacinthe Rigaud, Portrait of Philippe de Courcillon, Marquis de Dangeau, 1702, oil on canvas, 162 x 150 cm, Versailles, Musée National du Chateau Eugène Delacroix, Frédéric Chopin, 1838; oil on canvas, 45.7 x 37.5 cm; Paris, Louvre Hyacinthe Rigaud, Portrait of Everhard Jabach, 1688, oil on canvas, 58.5 x 47 cm; Cologne, Wallraff-Richartz Museum Ingres, Portrait of Monsieur Bertin, 1832, oil on canvas, 116 x 95 cm; Paris, Louvre Leonardo da Vinci, Presumed self-portrait at about 29 from the unfinished Adoration of the Magi c. -

Wye College, Wye, Kent

WYE COLLEGE, WYE, KENT March 2017 NGR: 6055 1469 Conditions of Release This document has been prepared for the titled project, or named part thereof, and should not be relied on or used for any other project without an independent check being carried out as to its suitability and prior written authority of Canterbury Archaeological Trust Ltd being obtained. Canterbury Archaeological Trust Ltd accepts no responsibility or liability for this document to any party other than the person by whom it was commissioned. This document has been produced for the purpose of assessment and evaluation only. To the extent that this report is based on information supplied by other parties, Canterbury Archaeological Trust Ltd accepts no liability for any loss or damage suffered by the client, whether contractual or otherwise, stemming from any conclusions based on data supplied by parties other than Canterbury Archaeological Trust Ltd and used by Canterbury Archaeological Trust Ltd in preparing this report. This report must not be altered, truncated, précised or added to except by way of addendum and/or errata authorized and executed by Canterbury Archaeological Trust Ltd. All rights, including translation, reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of Canterbury Archaeological Trust Limited Canterbury Archaeological Trust Ltd 92a Broad Street, Canterbury, Kent, CT1 2LU Tel +44 (0)1227 462062 Fax +44 (0)1227 784724 email: [email protected] www.canterburytrust.co.uk CONTENTS 1 ..... INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ -

Weekly List of Planning Consultations 24.06.2021

CONSERVATION CASES PROCESSED BY THE GARDENS TRUST 24.06.2021 This is a list of all the conservation consultations that The Gardens Trust has logged as receiving over the past week, consisting mainly, but not entirely, of planning applications. When assessing this list to see which cases CGTs may wish to engage with, it should be remembered that the GT will only be looking at a very small minority. SITE COUNTY SENT BY REFERENCE GT REF DATE GR PROPOSAL RESPONSE RECEIVED AD BY E ENGLAND Battlesden Park Bedfordshire Central CB/21/02605/VOC E21/0525 24/06/2021 II PLANNING APPLICATION Variation of 14/07/2021 Bedfordshire http://www.centralbedfo Conditions 2 and 22 of planning DC rdshire.gov.uk/planning- permission CB/16/01389/FULL register Installation of a single wind turbine with a maximum tip height of 143.5m (hub height 100m; rotor diameter of 87.0m), substation, hardstanding area, access track, underground cabling and associated infrastructure. The variation is to increase the rotor diameter of the wind turbine from 87.0m to 115.0m. This will also marginally increase the maximum turbine tip height from 143.5m to 147.0m. Land off A5 Checkley Wood Farm Watling Street Leighton Buzzard, LU7 9LG. MISCELLANEOUS Moggerhanger Park Bedfordshire Central CB/21/02832/FULL E21/0534 24/06/2021 II PLANNING APPLICATION (Re- 15/07/2021 Bedfordshire http://www.centralbedfo submission of planning permission DC rdshire.gov.uk/planning- CB/20/04680/FULL) To change size and register shape of horse exercise/ménage area from 20 by 40 metres to 30 by 40 metres and rotated 90 degrees from current approved position for private noncommercial use.