Poverty in Small-Scale Fishing Communities in Bangladesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of the Legislature in Upholding the Rule of Law in Bangladesh Md

The Role of the Legislature in Upholding the Rule of Law in Bangladesh Md. Mostafijur Rahman 1 Abstract : In the contemporary global politics the rule of law is considered as the pre-requisite for better democracy, socio-economic development and good govern- ance. It is also essential in the creation and advancement of citizens’ rights of a civilized society and being considered for solving many problems in the developing country. The foremost role of the legislature-as second branch of government to recognise the rights of citizens and to assure the rule of law prevails. In order to achieve this goal the legislature among the pillars of a state should be constructive, effective, functional and meaningful. Although the rule of law is the basic feature of the constitution of Bangladesh the current state of the rule of law is a frustration because, almost in all cases, it does not favour the rights of the common people. Under the circumstances, the existence of the rule of law without an effective parlia- ment is conceivable. The main purpose of this study is to examine to what extent the parliament plays a role in upholding the rule of law in Bangladesh and conclude with pragmatic way forward accordingly. Keywords: Rule of law, principles of law, citizens’ rights, legislature, electoral procedure, legislative process. Introduction The ‘rule of law’ is opposed to ‘rule of man’. The term ‘rule of law’ is derived from the French phrase la Principe de legalite (the princi- ple of legality) which refers to a government based on principles of law and not of men. -

1992-Vol18-No4web.Pdf

Louise Brewster Miller 1900-1992 Bright Hours WOULD LIKE TO again dedicate this It was therefore one of life's precious neth Shewmaker., a Lvremier Webster page to a member of our fly-fishing and unpredictable serendipities when I scholar and history professor at Dart- Icommunity who recently passed married a fly fisherman and (at thirty- mouth College. Read this lively piece away, this time in a personal farewell to two) discovered a new dimension to this and see if you don't agree that Daniel my own angling role model. woman (aged eighty-five) as we stood Webster would have made a grand fish- My grandmother, Louise Brewster shoulder to shoulder in the soft dusk on ing buddy. Miller, died on June 30, 1992 at the age the Battenkill over the course of what I also introduce Gordon Wickstrom of ninety-two in Noroton Heights, Con- was to be the last few summers left to of Boulder, Colorado, who writes en- necticut. Widow of Sparse Grey Hackle us. She was adept, graceful, and above thusiastically about fishing's postwar era (Alfred Waterbury Miller, 1892-i983), all a determined handler of the gleam- and the multitalented Lou Feierabend Aamie, as we called her, learned to fly ing Garrison rod "Garry" had made for and his technically innovative five-strip fish early on in her marriage, figuring it her so many years ago. I was awed and rods. Finallv.i I welcome Maxine Ather- was the only way she was going to see humbled by her skill. ton of Dorset, Vermont, to the pages of anything of her fishing-nuts husband. -

100+ Silent Auction Basket Ideas! Tips: Ask for Donations for the Different Items

100+ Silent Auction Basket Ideas! Tips: Ask for donations for the different items. Split the items up among you & your team members. ***This document will be posted on www.relayforlife.org/scottcountymn.*** 1. Ice Cream Basket - toppings, sundae dishes, vegetable basket, meat thermometer, apron, waffle bowls and cones, sprinkles, ice cream skewers scoop, cherries, Culver’s gift certificate 11. I Love Books Basket - favorite children’s 2. Art Basket - crayons, paints, construction books, book characters, book marks, gift paper, play dough, colored pencils, sidewalk certificate to Barnes & Noble chalk, paint brushes, finger paints, finger paint paper, glitter, markers, scissors, stickers 12. Fishing Tackle Box - tackle box, fishing line, bobbers, lures, fishing weights, fishing net, 3. Movie Night - candy, microwave popcorn, Swedish fish movie gift certificate/ passes, blockbuster/video card, popcorn bowls 13. Wine & Cheese Basket - wine gift certificates, cheese tray/platter, wine glasses, 4. Coffee & Tea Basket - flavored coffees, corkscrew, wine topper, wine guide, wine coffee mugs, creamers, carafe, flavored teas, vacuum, wine charms, decanter, napkins, tea strainer, creamers, biscotti different cheeses 5. Beach Bag - suntan lotion, blanket, towels, 14. Martini Basket - martini glasses, gift beach chairs, sand pails/ shovels, beach ball, certificate for martini mixes, olives, olive picks, underwater camera shaker, napkins, plates, cocktail book 6. Game Night - family game- Go Fish, Uno, 15. Party Baskets (1—Spiderman and 1—Dora) Crazy Eights, regular deck of cards, Old Maids, tablecloth, plates, napkins, silverware, piñata, carrying storage tote disposable camera, balloons, decorations, gift certificate for DQ or bakery cake, gift bags 7. Chocolate Lover’s Basket - hot cocoa, different chocolates, truffles, chocolate 16. -

POVERTY and REFORMS in INDIA T. N. Srinivasan1

December 1999 POVERTY AND REFORMS IN INDIA T. N. Srinivasan1 Samuel C. Park, Jr. Professor of Economics Chairman, Department of Economics Yale University 1. Introduction The overarching objective of India's development strategy has always been the eradication of mass poverty. This objective has been articulated in several development plans, ranging from those published in the pre-independence era by individuals and organizations to the nine five year plans, and annual development plans since 1950 (Srinivasan 1999, lecture 3). However actual achievement has been very modest. In year 1997, five decades after independence, a little over a third of India's nearly billion population is estimated to be poor according to India's National Sample Survey (Table 1). It is also clear from the same table that until the late seventies, the national poverty ratio fluctuated with no significant time trend, between a low of 42.63 percent during April-September 1952 to a high of 62 percent July 1966-June 1967, the second of two successive years of severe drought. Then between July 1977-June 1978 and July 1990-June 1991, just prior to the introduction of systemic reforms of the economy following a severe economic crisis, the national poverty ratio declined significantly from 48.36 percent to 35.49 percent. The macroeconomic stabilization measures adopted at the same time as systemic reforms in July 1991 resulted in the stagnation of real GDP in 1991-92 relative to the previous 1I have drawn extensively on the research of Gaurav Datt and Martin Ravallion of the World Bank in writing this note. -

Cricket World Cup Begins Mar 8 Schedule on Page-3

www.Asia Times.US NRI Global Edition Email: [email protected] March 2016 Vol 7, Issue 3 Cricket World Cup begins Mar 8 Schedule on page-3 Indian Team: Pakistan Team: Shahid Afridi (c), Anwar Ali, Ahmed Shehzad MS Dhoni (capt, wk), Shikhar Dhawan, Rohit Mohammad Hafeez Bangladesh Team: Sharma, Virat Kohli, Ajinkya Rahane, Yuvraj Shoaib Malik, Mohammad Irfan Squad: Tamim Iqbal, Soumya Sarkar, Moham- Singh, Suresh Raina, R Ashwin, Ravindra Jadeja, Sharjeel Khan, Wahab Riaz mad Mithun, Shakib Al Hasan, Mushfiqur Ra- Mohammed Shami, Harbhajan Singh, Jasprit Mohammad Nawaz, Muhammad Sami him, Sabbir Rahman, Mashrafe Mortaza (capt), Bumrah, Pawan Negi, Ashish Nehra, Hardik Khalid Latif, Mohammad Amir Mahmudullah Riyad, Nasir Hossain, Nurul Pandya. Umar Akmal, Sarfraz Ahmed, Imad Wasim Hasan, Arafat Sunny, Mustafizur Rahman, Al- Amin Hossain, Taskin Ahmed and Abu Hider. Australia Team: Steven Smith (c), David Warner (vc), Ashton Agar, Nathan Coulter-Nile, James Faulkner, Aaron Finch, John Hastings, Josh Hazlewood, Usman Khawaja, Mitchell Marsh, Glenn Max- well, Peter Nevill (wk), Andrew Tye, Shane Watson, Adam Zampa England: Eoin Morgan (c), Alex Hales, Ja- Asia Times is Globalizing son Roy, Joe Root, Jos Buttler, James Vince, Ben Now appointing Stokes, Moeen Ali, Chris Jordan, Adil Rashid, David Willey, Steven Finn, Reece Topley, Sam Bureau Chiefs to represent Billings, Liam Dawson New Zealand Team: Asia Times in ALL cities Kane Williamson (c), Corey Anderson, Trent Worldwide Boult, Grant Elliott, Martin Guptill, Mitchell McClenaghan, -

Strengthening of Panchayats in India: Comparing Devolution Across States

Strengthening of Panchayats in India: Comparing Devolution across States Empirical Assessment - 2012-13 April 2013 Sponsored by Ministry of Panchayati Raj Government of India The Indian Institute of Public Administration New Delhi Strengthening of Panchayats in India: Comparing Devolution across States Empirical Assessment - 2012-13 V N Alok The Indian Institute of Public Administration New Delhi Foreword It is the twentieth anniversary of the 73rd Amendment of the Constitution, whereby Panchayats were given constitu- tional status.While the mandatory provisions of the Constitution regarding elections and reservations are adhered to in all States, the devolution of powers and resources to Panchayats from the States has been highly uneven across States. To motivate States to devolve powers and responsibilities to Panchayats and put in place an accountability frame- work, the Ministry of Panchayati Raj, Government of India, ranks States and provides incentives under the Panchayat Empowerment and Accountability Scheme (PEAIS) in accordance with their performance as measured on a Devo- lution Index computed by an independent institution. The Indian Institute of Public Administration (IIPA) has been conducting the study and constructing the index while continuously refining the same for the last four years. In addition to indices on the cumulative performance of States with respect to the devolution of powers and resources to Panchayats, an index on their incremental performance,i.e. initiatives taken during the year, was introduced in the year 2010-11. Since then, States have been awarded for their recent exemplary initiatives in strengthening Panchayats. The Report on"Strengthening of Panchayats in India: Comparing Devolution across States - Empirical Assessment 2012-13" further refines the Devolution Index by adding two more pillars of performance i.e. -

Convention on the Rights of the Child

70+6'& 0#6+105 %4% %QPXGPVKQPQPVJG Distr. 4KIJVUQHVJG%JKN GENERAL CRC/C/65/Add.22 14 March 2003 Original: ENGLISH COMMITTEE ON THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD CONSIDERATION OF REPORTS SUBMITTED BY STATES PARTIES UNDER ARTICLE 44 OF THE CONVENTION Second periodic reports of States parties due in 1997 BANGLADESH* [12 June 2001] * For the initial report submitted by the Government of Bangladesh, see CRC/C/3/Add.38 and 49; for its consideration by the Committee, see documents CRC/C/SR.380-382 and CRC/C/15/Add.74. GE.03-40776 (E) 120503 CRC/C/65/Add.22 page 2 CONTENTS Paragraphs Page I. BACKGROUND ......................................................................... 1 - 5 3 II. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................... 6 - 16 4 A. Land and people .................................................................. 7 - 10 4 B. General legal framework .................................................... 11 - 16 5 III. IMPLEMENTATION OF THE CONVENTION ........................ 17 - 408 6 A. General measures of implementation ................................. 17 - 44 6 B. Definition of the child ......................................................... 45 - 47 13 C. General principles ............................................................... 48 - 68 14 D. Civil rights and freedoms ................................................... 69 - 112 18 E. Family environment and alternative care ........................... 113 - 152 25 F. Basic health and welfare .................................................... -

Fishing Methods and Gears in Panay Island, Philippines

Fishing Methods and Gears in Panay Island, Philippines 著者 KAWAMURA Gunzo, BAGARINAO Teodora journal or 鹿児島大学水産学部紀要=Memoirs of Faculty of publication title Fisheries Kagoshima University volume 29 page range 81-121 別言語のタイトル フィリピン, パナイ島の漁具漁法 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10232/13182 Mem. Fac. Fish., Kagoshima Univ. Vol.29 pp. 81-121 (1980) Fishing Methods and Gears in Panay Island, Philippines*1 Gunzo Kawamura*2 and Teodora Bagarinao*3 Abstract The authors surveyed the fishing methods and gears in Panay and smaller neighboring islands in the Philippines in September-December 1979 and in March-May 1980. This paper is a report on the fishing methods and gears used in these islands, with special focus on the traditional and primitive ones. The term "fishing" is commonly used to mean the capture of many aquatic animals — fishes, crustaceans, mollusks, coelenterates, echinoderms, sponges, and even birds and mammals. Moreover, the harvesting of algae underwater or from the intertidal zone is often an important job for the fishermen. Fishing method is the manner by which the aquatic organisms are captured or collected; fishing gear is the implement developed for the purpose. Oftentimes, the gear alone is not sufficient and auxiliary instruments have to be used to realize a method. A fishing method can be applied by means of various gears, just as a fishing gear can sometimes be used in the appli cation of several methods. Commonly, only commercial fishing is covered in fisheries reports. Although traditional and primitive fishing is done on a small scale, it is still very important from the viewpoint of supply of animal protein. -

Snakeheadsnepal Pakistan − (Pisces,India Channidae) PACIFIC OCEAN a Biologicalmyanmar Synopsis Vietnam

Mongolia North Korea Afghan- China South Japan istan Korea Iran SnakeheadsNepal Pakistan − (Pisces,India Channidae) PACIFIC OCEAN A BiologicalMyanmar Synopsis Vietnam and Risk Assessment Philippines Thailand Malaysia INDIAN OCEAN Indonesia Indonesia U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1251 SNAKEHEADS (Pisces, Channidae)— A Biological Synopsis and Risk Assessment By Walter R. Courtenay, Jr., and James D. Williams U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1251 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GALE A. NORTON, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES G. GROAT, Director Use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. Copyrighted material reprinted with permission. 2004 For additional information write to: Walter R. Courtenay, Jr. Florida Integrated Science Center U.S. Geological Survey 7920 N.W. 71st Street Gainesville, Florida 32653 For additional copies please contact: U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services Box 25286 Denver, Colorado 80225-0286 Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Walter R. Courtenay, Jr., and James D. Williams Snakeheads (Pisces, Channidae)—A Biological Synopsis and Risk Assessment / by Walter R. Courtenay, Jr., and James D. Williams p. cm. — (U.S. Geological Survey circular ; 1251) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN.0-607-93720 (alk. paper) 1. Snakeheads — Pisces, Channidae— Invasive Species 2. Biological Synopsis and Risk Assessment. Title. II. Series. QL653.N8D64 2004 597.8’09768’89—dc22 CONTENTS Abstract . 1 Introduction . 2 Literature Review and Background Information . 4 Taxonomy and Synonymy . -

1 Poverty, Income Inequality and Growth In

POVERTY, INCOME INEQUALITY AND GROWTH IN BANGLADESH: REVISITED KARL-MARX MD NIAZ MURSHED CHOWDHURY Department of Economics University of Nevada Reno [email protected] MD. MOBARAK HOSSAIN Department of Economics University of Nevada Reno ABSTRACT This study tries to find the relationship among poverty inequality and growth. It also tries to connect the Karl Marx’s thoughts on functional income distribution and inequality in capitalism. Using the Household Income and Expenditure Survey of 2010 and 2016 this study attempt to figure out the relationship among them. In Bangladesh about 24.3% of the population is living under poverty lines and 12.3% of its population is living under the extreme poverty line. The major finding of this study is poverty has reduced significantly from 2000 to 2016, which is more than 100% but in recent time poverty reduction has slowed down. Despite the accelerating economic growth, the income inequality also increasing where the rate of urban inequality exceed the rural income inequality. Slower and unequal household consumption growth makes sloth the rate of poverty reduction. Average annual consumption fell from 1.8% to 1.4% from 2010 to 2016 and poorer households experienced slower consumption growth compared to richer households. KEYWORDS: Bangladesh; Inequality; Poverty; Distribution, GDP growth 1 I. INTRODUCTION Global inequality is the major concern in the recent era, which is rising at an alarming rate. According to recent Oxfam report, 82% of the wealth generated last year went to the richest 1% of the global population, which the 3.7% billion people who make up the poorest half of the world population had no increase in their wealth in another word poorest half of the world got nothing. -

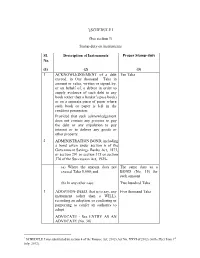

[SCHEDULE I (See Section 3) Stamp Duty on Instruments Sl. No. Description of Instruments Proper Stamp-Duty (1) (2) (3) 1 ACKNOWL

1[SCHEDULE I (See section 3) Stamp duty on instruments Sl. Description of Instruments Proper Stamp-duty No. (1) (2) (3) 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT of a debt Ten Taka exceed, in One thousand Taka in amount or value, written or signed by, or on behalf of, a debtor in order to supply evidence of such debt in any book (other than a banker’s pass book) or on a separate piece of paper where such book or paper is left in the creditors possession: Provided that such acknowledgement does not contain any promise to pay the debt or any stipulation to pay interest or to deliver any goods or other property. 2 ADMINISTRATION BOND, including a bond given under section 6 of the Government Savings Banks Act, 1873, or section 291 or section 375 or section 376 of the Succession Act, 1925- (a) Where the amount does not The same duty as a exceed Taka 5,000; and BOND (No. 15) for such amount (b) In any other case. Two hundred Taka 3 ADOPTION-DEED, that is to say, any Five thousand Taka instrument (other than a WILL), recording an adoption, or conferring or purporting to confer an authority to adopt. ADVOCATE - See ENTRY AS AN ADVOCATE (No. 30) 1 SCHEDULE I was substituted by section 4 of the Finance Act, 2012 (Act No. XXVI of 2012) (with effect from 1st July, 2012). 4 AFFIDAVIT, including an affirmation Two hundred Taka or declaration in the case of persons by law allowed to affirm or declare instead of swearing. EXEMPTIONS Affidavit or declaration in writing when made- (a) As a condition of enlistment under the Army Act, 1952; (b) For the immediate purpose of being field or used in any court or before the officer of any court; or (c) For the sole purpose of enabling any person to receive any pension or charitable allowance. -

Productivity and Constraints of Artisanal Fisher Folks in Some Local Government of Rivers State, Nigeria

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Agriculture and Animal Science Volume 8 ~ Issue 2 (2021) pp: 32-38 ISSN(Online) : 2321-9459 www.questjournals.org Research Paper Productivity and Constraints of Artisanal Fisher folks in Some Local Government of Rivers State, Nigeria George A.D.I1 ;Akinrotimi O.A2*and Nwokoma, U. K3 1.3Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Environment, Faculty of Agriculture, Rivers State University, Nkpolu- Oroworukwo, Port Harcourt, Nigeria 2African Regional Aquaculture Centre/Nigerian Institute for Oceanography and Marine Research, P.M.B 5122, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria *Corresponding author Akinrotimi O.A ABSTRACT: Productivity and constraints of artisanal fisher folks in some local government of Rivers State was carried out. Prepared questionnaires were used to sourced vital information from a total of one hundred and fifty respondents (150) in three communities (Bugunma, Harristown and Obonnoma) in Kalabari Kingdom of Rivers State. The data generated from the study were analyzed, using descriptive statistics, budgetary analysis and regression analysis (ANOVA). The results revealed that 54.6% has their major source of capital from personal saving. The budgetary analysis showed that the gross margin of N3 The ANOVA showed that household size, highest educational qualification and fishing experience has significant impact on the output level of the fishers.0,093 were obtained by fisherman/day. The common catch species of fish are shiny nose (Polynaemidae) 82.3%, Tilapia 80.85%, and Cat fish 80.1%. While the common types of fishing gear used were hook and line 95.0%, Cast net and Scoop net (86.5%), Fishing basket 85.1% and Fishing trap 84.4%.