Opening Pandora's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seethings and Seatings

SEETHINGS AND SEATINGS Strategies for Women’s Political Participation in Asia Pacific Researchers: Bernadette Libres (the Philippines), Bermet Stakeeva (Kyrgyzstan), D. Geetha (India), Naeemah Khan (Fiji), Hong Chun Hee (Korea) and Saliha Hassan (Malaysia) Editors: Rashila Ramli, Elisa Tita Lubi and Nurgul Djanaeva A Project of the Task Force on Women’s Participation in Political Processes APWLD COPYRIGHT Copyright © 2005 Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development (APWLD) Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised and encouraged, provided the source is fully acknowledged. ISBN: 974-93775-1-6 Editorial board: Rashila Ramli, Elisa Tita Lubi and Nurgul Djanaeva Concept for design and layout: Nalini Singh and Tomoko Kashiwazaki Copy editors: Haresh Advani and Nalini Singh Cover design and layout: Byheart design Cover batik image: Titi Soentoro Photographs of research subjects: Researchers and research subjects Published by Asia Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development (APWLD) 189/3 Changklan Road, Amphoe Muang, Chiang Mai 50101, Thailand Tel nos :(66) 53 284527, 284856 Fax: (66) 53 280847 Email: [email protected]; website: www.apwld.org CONTENT Acknowledgements...................................................................................................... v Message from Regional Coordinator .....................................................................vii Foreword ..................................................................................................................... -

REPORT on Handicraft Activities in Central Asia: Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan in 2013 Prepared by D.Chochunbaeva, Vice-President of WCC-APR for Central Asia

REPORT on Handicraft activities in Central Asia: Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan in 2013 Prepared by D.Chochunbaeva, Vice-president of WCC-APR for Central Asia Kyrgyzstan: 1. During 2013 there were organized 7 short craft fairs. This craft fairs are organized in Bishkek, capital of Kyrgyzstan, every month. Usually 23-25 Kyrgyz, Uzbek and Tajik craftsmen take part at fairs. Schedule of the craft fairs: Feb 9-10, March 16-17, April 5-6, May 22-25, October 19-20, November 22-23, December 7-8. 2. Since October 2012 to March 2014 CACSARC-kg takes part in implementing of the Project "Advancing women’s economic opportunities in Fergana valley handicraft and textile supply chain" in partnership with the RCE KG (Resource Center of the Development for Sustainable Development in Kyrgyzstan). There were several International Experts on Handicraft Development being involved in the Project activities: WCC-APR Board Members Ms. Manjari Nirula (India) and Mr. Edric Ong (Malaysia) have been providing support in creation of the craft production-marketing chain in Fergana Valley and introducing Central Asian handicrafts to the different markets; Ms. Geraldine Hurez (France) – have been completing and adapting handicraft items “Fergana Valley Collection” for the European market, particularly for the Maison et Objet; Ms. Karen Gibbs (USA, “ByHand” Consulting) – have been developing selecting craft production to be introduced for American market (at New York Gift Fair, Feb 2014). 1) Within Project activities there were 23 trainings on different craft technologies and marketing were provided for more than 225 craftsmen all over Fergana Valley in Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. -

Genetic Diversity of Echinococcus Multilocularis and Echinococcus Granulosus Sensu Lato in Kyrgyzstan: the A2 Haplotype of E

PLOS NEGLECTED TROPICAL DISEASES RESEARCH ARTICLE Genetic diversity of Echinococcus multilocularis and Echinococcus granulosus sensu lato in Kyrgyzstan: The A2 haplotype of E. multilocularis is the predominant variant infecting humans 1☯ 1☯ 2 Cristian A. Alvarez RojasID *, Philipp A. Kronenberg , Sezdbek Aitbaev , Rakhatbek a1111111111 A. Omorov2, Kubanychbek K. Abdykerimov3, Giulia Paternoster3, Beat MuÈ llhaupt4, a1111111111 Paul Torgerson3, Peter Deplazes1 a1111111111 a1111111111 1 Institute of Parasitology, Vetsuisse and Medical Faculty, University of ZuÈrich, ZuÈrich, Switzerland, 2 City Clinical Hospital #1, Surgical Department, Faculty of Surgery of the Kyrgyz State Medical Academy, Bishkek, a1111111111 Kyrgyzstan, 3 Section of Epidemiology, Vetsuisse Faculty, University of ZuÈrich, ZuÈrich, Switzerland, 4 Clinics of Hepatology and Gastroenterology, University Hospital of ZuÈrich, ZuÈrich, Switzerland ☯ These authors contributed equally to this work. * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Citation: Alvarez Rojas CA, Kronenberg PA, Aitbaev S, Omorov RA, Abdykerimov KK, Paternoster G, et Abstract al. (2020) Genetic diversity of Echinococcus multilocularis and Echinococcus granulosus sensu Alveolar and cystic echinococcosis (AE, CE) caused by E. multilocularis and E. granulosus lato in Kyrgyzstan: The A2 haplotype of E. s.l., respectively, are considered emerging zoonotic diseases in Kyrgyzstan with some of multilocularis is the predominant variant infecting the world highest regional incidences. Little is known regarding the molecular variability of humans. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 14(5): e0008242. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008242 both species in Kyrgyzstan. In this study we provide molecular data from a total of 72 para- site isolates derived from humans (52 AE and 20 CE patients) and 43 samples from dogs Editor: Adriano Casulli, Istituto Superiore Di Sanita, ITALY (23 infected with E. -

Detailed Climate Change Assessment

Climate Change and Disaster Resilient Water Resources Sector Project (RRP KGZ 51081-002) DETAILED CLIMATE CHANGE ASSESSMENT Table of contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 I. COUNTRY BACKGROUND AND ITS CLIMATE 3 A. BACKGROUND 3 B. THE CLIMATE OF KYRGYZSTAN 4 C. CURRENT CLIMATE VARIABILITY AND CLIMATE CHANGE 6 II. BRIEF INTRODUCTION OF GLOBAL CLIMATE MODELS USED IN THIS CVRA STUDY 16 A. MODEL GENERATED CLIMATE DATA 16 B. DATA ANALYSIS TOOLS 20 C. DATA AND CHOICE OF METRICS 21 D. VALIDATION OF GLOBAL CLIMATE MODELS TO BASELINE OBSERVED (CRU, UK) CLIMATOLOGY 22 E. KYRGYZSTAN CLIMATE CHANGE ISSUES, POLICIES AND INVESTMENTS 28 III. CLIMATE CHANGE PROJECTIONS AND EXTREMES 29 A. KYRGYZSTAN’S MEAN CLIMATE & SEASONAL VARIABILITY –KEY ISSUES 29 B. SIMULATION OF FUTURE CLIMATE OF KYRGYZSTAN & SELECTED OBLASTS 31 C. UNCERTAINTIES IN FUTURE PROJECTIONS 69 D. SUMMARY - KEY FINDINGS ON CLIMATE CHANGE SCENARIOS 69 IV. IMPLICATIONS OF PROJECTED CHANGES IN CLIMATE ON THE RISKS AT PROPOSED SUB-PROJECT LEVEL AND ASSOCIATED VULNERABILITIES 72 A. THE SHORT-LISTED SUB-PROJECT: INTRODUCTION 72 B. CLIMATE RISK SCREENING AND VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT OF THE SHORT-LISTED SUB-PROJECT 73 V. CLIMATE CHANGE & DISASTER RISK FRAMEWORK FOR CLIMATE RESILIENCE 89 A. MAINSTREAMING FRAMEWORK FOR CCA AND DRR 89 B. POTENTIAL ADAPTATION RESPONSES / STRATEGIES 90 C. REHABILITATION OF EXISTING HYDROMET MONITORING NETWORK AND REQUIREMENTS OF ADDITIONAL WEATHER STATIONS IN KYRGYZ REPUBLIC 97 Tables TABLE 1: AVERAGE MONTHLY TEMPERATURES AND PRECIPITATION - BISHKEK 5 TABLE 2: AVERAGE MONTHLY -

BA Country Report of Kyrgyzstan Part 1 Macro Level

Informal Governance and Corruption – Transcending the Principal Agent and Collective Action Paradigms Kyrgyzstan Country Report Part 1 Macro Level Aksana Ismailbekova | July 2018 Basel Institute on Governance Steinenring 60 | 4051 Basel, Switzerland | +41 61 205 55 11 [email protected] | www.baselgovernance.org BASEL INSTITUTE ON GOVERNANCE This research has been funded by the UK government's Department for International Development (DFID) and the British Academy through the British Academy/DFID Anti-Corruption Evidence Programme. However, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the British Academy or DFID. Dr Aksana Ismailbekova, Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Advokatenweg 36 06114 Halle (Saale), Germany, [email protected] 1 BASEL INSTITUTE ON GOVERNANCE Table of contents Abstract 3 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Informal Governance and Corruption: Rationale and project background 4 1.2 Informal governance in Kyrgyzstan 4 1.3 Conceptual approach 6 1.4 Research design and methods 6 2 Informal governance and the lineage associations: 1991–2005 7 2.1 Askar Akaev and the transition to Post-Soviet governance regime 7 2.2 Co-optation: Political family networks 8 2.3 Control: social sanctions, demonstrative punishment and selective law enforcement 11 2.4 Camouflage: the illusion of inclusive democracy and charitable contributions 13 2.5 The Tulip Revolution and the collapse of the Akaev networks 13 3 Epoch of Bakiev from 2005–2010 14 3.1 Network re-accommodation in the aftermath of the Tulip Revolution -

United Nations ___Economic Commission for Europe Use of Clean, Renewable And/Or Alternative Energy Technologies In

1 UNITED NATIONS _____________ ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE SUSTAINABLE ENERGY DIVISION USE OF CLEAN, RENEWABLE AND/OR ALTERNATIVE ENERGY TECHNOLOGIES IN RURAL DISTRICTS OF KYRGYZSTAN Shamil Dikambaev Bishkek 2015 2 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 1. Assessment of proposed decisions for autonomous and network access to power services in rural and remote districts of Kyrgyzstan ...................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. General description of power generation and consumption ............................................................ 5 in Kyrgyzstan ................................................................................................................................................. 5 1.2. Issues of power supply to rural and remote districts of Kyrgyzstan .................................................... 10 1.3. Assessment of using renewable power technologies for rural districts of Kyrgyzstan in the current conditions .................................................................................................................................................... 20 2. Assessment of political measures, advanced practices and business models for support of rendering sustainable power services in the rural areas of Kyrgyzstan ...................................................................... 26 3. -

Reasserting Hegemony in Central Asia: Russian Policy in Post-2010 Kyrgyzstan

Comillas Journal of International Relations | nº 03 | 058-080 [2015] [ISSN 2386-5776] 58 DOI: cir.i03.y2015.005 REASSERTING HEGEMONY IN CENTRAL ASIA: RUSSIAN POLICY IN POST-2010 KYRGYZSTAN Reafirmar la hegemonía en Asia Central: las políticas rusas en Kirguistán tras 2010 David Lewis Department of Political Science Autor University of Exeter E-mail: [email protected] While there has been considerable international focus on Russia’s assertive foreign policies in Ukraine and the southern Caucasus, Moscow’s increasing influence in the former Soviet states Abstract of Central Asia has received much less attention. A shift in policy after 2010 has been particu- larly successful in the development of a much stronger Russian relationship with Kyrgyzstan, a state that had previously developed a moderately pro-Western foreign policy, and which plays a key strategic role in the region. Kyrgyzstan has downgraded security and political ties with Western states, joined the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), and developed closer security ties in the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO). This article analyses these policy shifts and characterises the new Russian stance as “hegemonic”, indicating both Rus- sian military, political and economic dominance in the relationship but also significant popular support in Kyrgyzstan for closer ties with Moscow. Russian policy has relied on an integrated approach to foreign policy that includes initiatives in the fields of security, economy and poli- tics, and also forms of “soft power” and cultural influence. The case of Kyrgyzstan suggests that analysing Russian policy within the framework of hegemony is a useful way to discuss both the potential for increased influence and the significant constraints faced by Russian policy-makers in the Eurasian region. -

Messages, Images and Media Channels Promoting Youth Radicalization in Kyrgyzstan

ANALYTICAL REPORT Action Research within the framework of the project “Social media for deradicalization in Kyrgyzstan: A model for Central Asia” Messages, images and media channels promoting youth radicalization in Kyrgyzstan Author and Main researcher: Inga Sikorskaya Edited by: Ikbalzhan Mirsaiitov and Mirgul Karimova ANALYTICAL REPORT ON ACTION RESEARCH Messages, images and media channels promoting youth radicalization in Kyrgyzstan January 2017 Author and Main researcher: Inga Sikorskaya Edited by: Ikbalzhan Mirsaiitov and Mirgul Karimova 1 Disclaimer: The opinions, views and conclusions expressed herein do not necessarily coincide with the views of Search for Common Ground, US State Department and other organizations. This is non- academic action research. Copyright©2017 Search for Common Ground 74 Erkindik Boulevard, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan 720045 Phone: +996 (312) 622-777 Fax: +996 (312) 622-777 www.sfcg.org Cover art: jimharold.com | Cover design: Mirgul Karimova When using and reproducing any materials published in this report, the source (Search for Common Ground) must be acknowledged. 2 Content Research Summary ……..…………….………………………………………….…………………………………………………4 Main findings …..……………………….………………………………………………………….…....…………………5 Recommendations for a “soft” approach to counter-radicalization …………….….….….……….…...9 Research goals, approaches, and data of respondents …..……………………….….….…………………….10 Analysis and trends ……………………….……..……………………………………………….………..………….……….…13 Methods and stages of recruitment …………………………………………………………………………………………………………14 -

Decentralization and Local Self Government

United Nations Development Programme Kyrgyz Republic Project Proposal Project title: Strengthening disaster response and risk assessment capacities in the Kyrgyz Republic and facilitating a regional dialogue for cooperation CP/UNDAF Outcome(s):1 By 2016, Disaster Risk Management framework in compliance with international standards, especially the Hyogo Framework of Action. Expected Output(s): Output 1. Risk assessment and monitoring capabilities of Crisis Management Centers enhanced for better socio-economic development programming. Output 2. National early warning capacities strengthened through developing infrastructure, rapid risk analysis, and information dissemination capacities Output 3. National response capacities strengthened through upgrading infrastructure of Emergency Rescue Facilities Output 4. Regional cooperation advocated for increasing dialogue and cooperation in disaster risk reduction Implementing partners: United Nations Development Programme Responsible parties: Ministries: Ministry of Emergency Situations, Ministry of Health Care, Central Asian Center for Disaster Response and Risk Reduction Local level partners: local state administrations, local self- governments, Civil Protection Commissions. Brief Description Within the framework of UNDAF 2005-2011 UNDP has made important contributions in disaster prevention and recovery through mainstreaming disaster risk management into decentralized policy- making (as recommended by a mid-term outcome evaluation) and in strengthening disaster response and coordination frameworks. -

Public Opinion Survey Residents of Kyrgyzstan

Public Opinion Survey Residents of Kyrgyzstan November 22 - December 4, 2018 Detailed Methodology • The survey was conducted by Dr. Rasa Alisauskiene of the public and market research company Baltic Surveys/The Gallup Organization on behalf of the International Republican Institute. The field work was carried out by SIAR Research and Consulting. • Data was collected throughout Kyrgyzstan on November 22 - December 4, 2018 through face-to-face interviews at respondents’ homes. • The sample consisted of 1,500 permanent residents of Kyrgyzstan aged 18 and older and eligible to vote. • A multistage probability sampling method was used, employing the random route and Kish Method for respondents’ selection procedures. • Stage one: All districts of Kyrgyzstan were grouped into seven regions plus Bishkek. Each region of Kyrgyzstan was surveyed. • Stage two: Settlements were selected at random. The number of selected settlements in each region was proportional to the share of population living in a particular type of the settlement in that region. • Stage three: Primary sampling units were described. • Demographic differences between the achieved sample and published census data are linked to migration patterns, with the population of Kyrgyzstani citizens working and residing abroad being disproportionately young and male. In an effort to stabilize sample distributions over time, IRI introduced a weighting scheme to this data which it will continue to use in the future. Due to this improvement in the methodology, shifts between this survey and the November 2017 survey (and prior) may appear larger than the actual change. For example, trends on internet usage reflect our adjustment to census-reported age and gender demographics. -

FROM 03.2010 to 12.2013 Programme

DELIVERY AS ONE (DAO) MPTF OFFICE GENERIC FINALPROGRAMME1 NARRATIVE REPORT REPORTING PERIOD: FROM 03.2010 TO 12.2013 Country, Locality(s), Priority Area(s) / Strategic Programme Title & Project Number Results2 Programme Title: Cross-border natural resources and Country: Kyrgyzstan conflict3 Localities: Batken, Leylek, Alabuka districts of Kyrgyzstan Programme Number (if applicable) 00046725 Isfara and Rasulov districts of Tajikistan 4 MPTF Office Project Reference Number: 00074593 Kasansai district of Uzbekistan Thematic Area: Crisis Prevention & Recovery Priority area/ strategic results: Risk Reduction/ Risk Management Participating Organization(s) Implementing Partners Organizations that have received direct funding from the Office of President of the Kyrgyz Republic MPTF Office under this programme Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kyrgyz Republic Oblast Administration of Jalalabad and Batken United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) District administration of Batken, Leylek, Alabuka, Isfara, United Nations Volunteers (UNV) Bobojon-Gafurov, Spitamen, Dzhabbor-Rasulov Local Self Governments (LSGs) in Osh (Nookat, Uzgen, Kara-Kulja districts), Jalal-Abad (Ala-Buka district), and Batken Provinces; Aksai, Samarkandek, Ak-Tatyr, Kara-Bak municipalities, Batken district, Batken Province Kulunda, Sumbula, Jany-Jer municipalities of Leylek district, Batken Province Oblast administration of Sugd Province, Tajikistan State Administrations of Isfara and Rasulov districts of Tajikistan Histevarz, Vorukh, Chorkukh, Ovchi, Lyakkon -

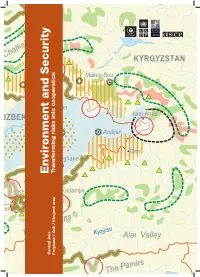

Environment and Security Thematic Issues for Possible ENVSEC Action

���������������������������������� Environment and Security / 1 �� ��� �� �� �� ������� ��� ���������� ��������� �� ��� �� ���������� �� � ���������� �������� �� ��������� �� �� �������� � �� �������� ������� ���������� ���������� �� �������� ��� �� ������� � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �� �� � � � ��� � �������� � � �������� � �������� ��������� Transforming risks into cooperation Transforming ������� and Security Environment ������� ������ ���������� �������� ������ � ����� ��� ��� ���� � ��� ������������ ��������� ��������� ��������� Central Asia / Osh Khujand area Ferghana � ����� ����� ���������� ��� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 2 / Environment and Security The United Nations Development Programme is the UN´s Global Development Network, advocating for change and connecting countries to knowledge, experience and resources to help people build a better life. It operates in 166 countries, working with them on responses to global and national development challenges. As they develop local capacity, the countries draw on the UNDP people and its wide range of partners. The UNDP network links and co-ordinates global and national efforts to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. The United Nations Environment Programme, as the world’s leading intergovernmental environmental organization, is the authoritative source of knowledge on the current state of,