Emancipation Celebration Full Score

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ellington-Lambert-Richards) 3

1. The Stevedore’s Serenade (Edelstein-Gordon-Ellington) 2. La Dee Doody Doo (Ellington-Lambert-Richards) 3. A Blues Serenade (Parish-Signorelli-Grande-Lytell) 4. Love In Swingtime (Lambert-Richards-Mills) 5. Please Forgive Me (Ellington-Gordon-Mills) 6. Lambeth Walk (Furber-Gay) 7. Prelude To A Kiss (Mills-Gordon-Ellington) 8. Hip Chic (Ellington) 9. Buffet Flat (Ellington) 10. Prelude To A Kiss (Mills-Gordon-Ellington) 11. There’s Something About An Old Love (Mills-Fien-Hudson) 12. The Jeep Is Jumpin’ (Ellington-Hodges) 13. Krum Elbow Blues (Ellington-Hodges) 14. Twits And Twerps (Ellington-Stewart) 15. Mighty Like The Blues (Feather) 16. Jazz Potpourri (Ellington) 17. T. T. On Toast lEllington-Mills) 18. Battle Of Swing (Ellington) 19. Portrait Of The Lion (Ellington) 20. (I Want) Something To Live For (Ellington-Strayhorn) 21. Solid Old Man (Ellington) 22. Cotton Club Stomp (Carney-Hodges-Ellington) 23. Doin’The Voom Voom (Miley-Ellington) 24. Way Low (Ellington) 25. Serenade To Sweden (Ellington) 26. In A Mizz (Johnson-Barnet) 27. I’m Checkin’ Out, Goo’m Bye (Ellington) 28. A Lonely Co-Ed (Ellington) 29. You Can Count On Me (Maxwell-Myrow) 30. Bouncing Buoyancy (Ellington) 31. The Sergeant Was Shy (Ellington) 32. Grievin’ (Strayhorn-Ellington) 33. Little Posey (Ellington) 34. I Never Felt This Way Before (Ellington) 35. Grievin’ (Strayhorn-Ellington) 36. Tootin Through The Roof (Ellington) 37. Weely (A Portrait Of Billy Strayhorn) (Ellington) 38. Killin’ Myself (Ellington) 39. Your Love Has Faded (Ellington) 40. Country Gal (Ellington) 41. Solitude (Ellington-De Lange-Mills) 42. Stormy Weather (Arlen-Köhler) 43. -

John Cornelius Hodges “Johnny” “Rabbit”

1 The ALTOSAX and SOPRANOSAX of JOHN CORNELIUS HODGES “JOHNNY” “RABBIT” Solographers: Jan Evensmo & Ulf Renberg Last update: Aug. 1, 2014, June 5, 2021 2 Born: Cambridge, Massachusetts, July 25, 1906 Died: NYC. May 11, 1970 Introduction: When I joined the Oslo Jazz Circle back in 1950s, there were in fact only three altosaxophonists who really mattered: Benny Carter, Johnny Hodges and Charlie Parker (in alphabetical order). JH’s playing with Duke Ellington, as well as numerous swing recording sessions made an unforgettable impression on me and my friends. It is time to go through his works and organize a solography! Early history: Played drums and piano, then sax at the age of 14; through his sister, he got to know Sidney Bechet, who gave him lessons. He followed Bechet in Willie ‘The Lion’ Smith’s quartet at the Rhythm Club (ca. 1924), then played with Bechet at the Club Basha (1925). Continued to live in Boston during the mid -1920s, travelling to New York for week-end ‘gigs’. Played with Bobby Sawyer (ca. 1925) and Lloyd Scott (ca. 1926), then from late 1926 worked regularly with Chick webb at Paddock Club, Savoy Ballroom, etc. Briefly with Luckey Roberts’ orchestra, then joined Duke Ellington in May 1928. With Duke until March 1951 when formed own small band (ref. John Chilton). Message: No jazz topic has been studied by more people and more systematically than Duke Ellington. So much has been written, culminating with Luciano Massagli & Giovanni M. Volonte: “The New Desor – An updated edition of Duke Ellington’s Story on Records 1924 – 1974”. -

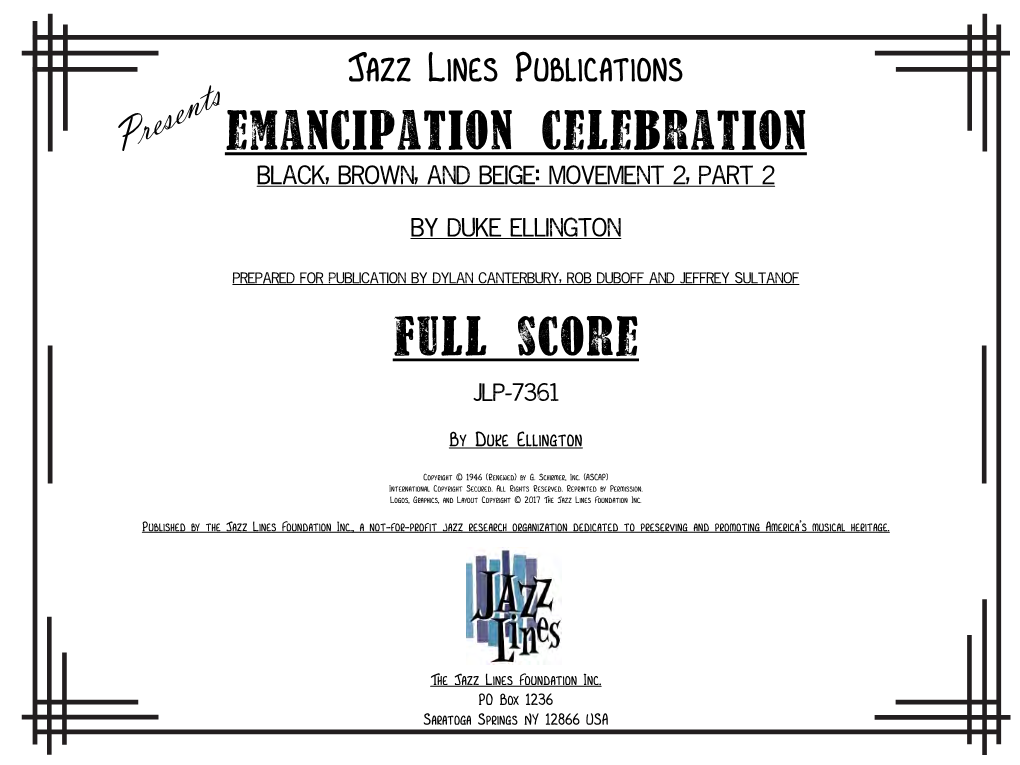

Black, Brown and Beige

Jazz Lines Publications Presents black, brown, and beige by duke ellington prepared for Publication by dylan canterbury, Rob DuBoff, and Jeffrey Sultanof complete full score jlp-7366 By Duke Ellington Copyright © 1946 (Renewed) by G. Schirmer, Inc. (ASCAP) International Copyright Secured. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by Permission. Logos, Graphics, and Layout Copyright © 2017 The Jazz Lines Foundation Inc. Published by the Jazz Lines Foundation Inc., a not-for-profit jazz research organization dedicated to preserving and promoting America’s musical heritage. The Jazz Lines Foundation Inc. PO Box 1236 Saratoga Springs NY 12866 USA duke ellington series black, brown, and beige (1943) Biographies: Edward Kennedy ‘Duke’ Ellington influenced millions of people both around the world and at home. In his fifty-year career he played over 20,000 performances in Europe, Latin America, the Middle East as well as Asia. Simply put, Ellington transcends boundaries and fills the world with a treasure trove of music that renews itself through every generation of fans and music-lovers. His legacy continues to live onward and will endure for generations to come. Wynton Marsalis said it best when he said, “His music sounds like America.” Because of the unmatched artistic heights to which he soared, no one deserves the phrase “beyond category” more than Ellington, for it aptly describes his life as well. When asked what inspired him to write, Ellington replied, “My men and my race are the inspiration of my work. I try to catch the character and mood and feeling of my people.” Duke Ellington is best remembered for the over 3,000 songs that he composed during his lifetime. -

The Development of Duke Ellington's Compositional Style: a Comparative Analysis of Three Selected Works

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Master's Theses Graduate School 2001 THE DEVELOPMENT OF DUKE ELLINGTON'S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THREE SELECTED WORKS Eric S. Strother University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Strother, Eric S., "THE DEVELOPMENT OF DUKE ELLINGTON'S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THREE SELECTED WORKS" (2001). University of Kentucky Master's Theses. 381. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_theses/381 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF THESIS THE DEVELOPMENT OF DUKE ELLINGTON’S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THREE SELECTED WORKS Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington’s compositions are significant to the study of jazz and American music in general. This study examines his compositional style through a comparative analysis of three works from each of his main stylistic periods. The analyses focus on form, instrumentation, texture and harmony, melody, tonality, and rhythm. Each piece is examined on its own and their significant features are compared. Eric S. Strother May 1, 2001 THE DEVELOPMENT OF DUKE ELLINGTON’S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THREE SELECTED WORKS By Eric Scott Strother Richard Domek Director of Thesis Kate Covington Director of Graduate Studies May 1, 2001 RULES FOR THE USE OF THESES Unpublished theses submitted for the Master’s degree and deposited in the University of Kentucky Library are as a rule open for inspection, but are to be used only with due regard to the rights of the authors. -

STANLEY FRANK DANCE (K25-28) He Was Born on 15 September

STANLEY FRANK DANCE (K25-28) He was born on 15 September 1910 in Braintree, Essex. Records were apparently plentiful at Framlingham, so during his time there he was fortunate that the children of local record executives were also in attendance. This gave him the opportunity to hear almost anything that was at hand. By the time he left Framlingham, he and some friends were avid record collectors, going so far as to import titles from the United States that were unavailable in England. By the time of his death, he had been writing about jazz longer than anyone had. He had served as book editor of JazzTimes from 1980 until December 1998, and was still contributing book and record reviews to that publication. At the time of his death he was also still listed as a contributor to Jazz Journal International , where his column "Lightly And Politely" was a feature for many years. He also wrote for The New York Herald- Tribune, The Saturday Review Of Literature and Music Journal, among many other publications. He wrote a number of books : The Jazz Era (1961); The World of Duke Ellington (1970); The Night People with Dicky Wells (1971); The World of Swing (1974); The World of Earl Hines (1977); Duke Ellington in Person: An Intimate Memoir with Mercer Ellington (1978); The World of Count Basie (1980); and Those Swinging Years with Charlie Barnet (1984). When John Hammond began writing for The Gramophone in 1931 he turned everything upside down and Stanley began corresponding with Hammond and they met for the first time during Hammond's trip to England in 1935. -

Guide to the Milt Gabler Papers

Guide to the Milt Gabler Papers NMAH.AC.0849 Paula Larich and Matthew Friedman 2004 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Personal Correspondence, 1945-1993..................................................... 5 Series 2: Writings, 1938 - 1991............................................................................... 7 Series 3: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music,, 1927-1981.................................. 10 Series 4: Personal Financial and Legal Records, 1947-2000............................... -

Duke Ellington 4 Meet the Ellingtonians 9 Additional Resources 15

ellington 101 a beginner’s guide Vital Statistics • One of the greatest composers of the 20th century • Composed nearly 2,000 works, including three-minute instrumental pieces, popular songs, large-scale suites, sacred music, film scores, and a nearly finished opera • Developed an extraordinary group of musicians, many of whom stayed with him for over 50 years • Played more than 20,000 performances over the course of his career • Influenced generations of pianists with his distinctive style and beautiful sound • Embraced the range of American music like no one else • Extended the scope and sound of jazz • Spread the language of jazz around the world ellington 101 a beginner’s guide Table of Contents A Brief Biography of Duke Ellington 4 Meet the Ellingtonians 9 Additional Resources 15 Duke’s artistic development and sustained achievement were among the most spectacular in the history of music. His was a distinctly democratic vision of music in which musicians developed their unique styles by selflessly contributing to the whole band’s sound . Few other artists of the last 100 years have been more successful at capturing humanity’s triumphs and tribulations in their work than this composer, bandleader, and pianist. He codified the sound of America in the 20th century. Wynton Marsalis Artistic Director, Jazz at Lincoln Center Ellington, 1934 I wrote “Black and Tan Fantasy” in a taxi coming down through Central Park on my way to a recording studio. I wrote “Mood Indigo” in 15 minutes. I wrote “Solitude” in 20 minutes in Chicago, standing up against a glass enclosure, waiting for another band to finish recording. -

![Frank Driggs Collection of Duke Ellington Photographic Reference Prints [Copy Prints]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8847/frank-driggs-collection-of-duke-ellington-photographic-reference-prints-copy-prints-1348847.webp)

Frank Driggs Collection of Duke Ellington Photographic Reference Prints [Copy Prints]

Frank Driggs Collection of Duke Ellington Photographic Reference Prints [copy prints] NMAH.AC.0389 NMAH Staff 2018 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents note................................................................................................ 2 Biographical/Historical note.............................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 3 Series 1: Band Members......................................................................................... 3 Series 2: Ellington at Piano...................................................................................... 5 Series 3: Candid Shots............................................................................................ 6 Series : Ellington -

Benjamin Francis Webster “Ben” “Frog” “Brute”

1 The TENORSAX of BENJAMIN FRANCIS WEBSTER “BEN” “FROG” “BRUTE” PART 1 (1931 – 1943) Solographer: Jan Evensmo Last update: April 13, 2018 2 Born: Kansas City, Missouri, March 27, 1909 Died: Amsterdam, Holland, Sept. 20, 1973 Introduction: Ben Webster was one of the all-time tenor saxophone greats with a long career of more than forty years. He was a favourite from the very first record with Duke Ellington from the early forties, and his music was always fascinating. I wrote his first solography in 1978 in Jazz Solography Series. Later his music appeared in the various ‘History of Jazz Tenor Saxophone’ volumes, including 1959. Later works will appear in due time on Jazz Archeology. He visited Norway several times, and I never forget when my friend Tor Haug served him fish for dinner! Early history: First studied violin, then piano. Attended Wilberforce College. Played piano in a silent-movie house in Amarillo, Texas. First professional work with Bretho Nelson's Band (out of Enid, Oklahoma), then, still on piano with Dutch Campbell's Band. Received early tuition on saxophone from Budd Johnson. Joined "family" band led by W.H. Young (Lester's father) in Campbell Kirkie, New Mexico, toured with the band for three months and began specialising on sax. With Gene Coy's Band on alto and tenor (early 1930), then on tenor with Jap Allen's Band (summer 1930). With Blanche Calloway from April 1931. Then joined Bennie Moten from Winter 1931-32 until early 1933 (including visit to New York). Then joined Willie Bryant's orchestra. -

Download the TROMBONE of Benny Morton

1 The TROMBONE of HENRY STERLING MORTON “BENNY” Solographers: Jan Evensmo & Ola Rønnow Last update: March 11, 2020 2 Born: NYC. Jan. 31, 1907 Died: NYC. Dec. 28, 1985 Introduction: Benny Morton was the most elegant of the black trombone players of the swing era, his music always had great qualities, and he had only a very few competitors on his instrument. He certainly deserves to be remembered! Early history: Step-father was a violinist. Studied at Textile High School in New York and began ‘gigging’ with school friends. Spent several years on and off with Billy Fowler’s orchestra from 1924. With Fletcher Henderson (1926-28). With Chick Webb (1930-31), then rejoined Fletcher Henderson (March 1931). With Don Redman from 1932 until 1937, joined Count Basie in October 1937. Left Basie in January 1940 to join Joe Sullivan’s band at Café Society. With Teddy Wilson sextet from July 1940 until 1943, then worked in Edmond Hall’s sextet (ref. John Chilton: Who’s Who of Jazz). Message: My co-solographer Ola Rønnow is a professional bass trombone player in the orchestra of the Norwegian National Opera , as well as playing trombone in Christiania 12, a local swing orchestra with a repertoire from the twenties and thirties. He has contributed many of the comments, particularly those which show a profound knowledge of the instrument, and an insight which I can only admire. 3 BENNY MORTON SOLOGRAPHY FLETCHER HENDERSON & HIS ORCHESTRA NYC. May 14, 1926 Russell Smith, Joe Smith, Rex Stewart (tp), Benny Morton (tb), Buster Bailey, Don Redman (cl, as), Coleman Hawkins (cl, ts), Fletcher Henderson (p), Charlie Dixon (bjo), Ralph Escudero (tu), Kaiser Ma rshall (dm). -

Emmett Berry

1 The TRUMPET of EMMETT BERRY Solographer: Jan Evensmo Last updated: July 18, 2019 2 Born: Macon, Georgia, July 23, 1915 Died: June 22, 1993 Introduction: Emmett Berry was an excellent swing trumpeter but possibly suffered by being overshadowed by the charismatic Roy Eldridge with a related style. It was quite obvious that he should be a candidate for a solography on internet! Early history: Raised in Cleveland, Ohio; began ‘gigging’ with local bands, then joined J. Frank Terry’s Chicago Nightingales in Toledo, Ohio (1932), left Terry in Albany, New York, in 1933and ‘gigged’ mainly in that area during the following three years. Joined Fletcher Henderson in late 1936, and remained until Fletcher disbanded in June 1939. With Horace Henderson until October 1940, briefly with Earl Hines, then with Teddy Wilson’s sextet from May 1941 until July 1942, then joined Raymond Scott at C.B.S. With Lionel Hampton from spring of 1943, week with Teddy Wilson in August 1943, briefly with Don Redman and Benny Carter, then again rejomed Teddy Wilson c. November 1943. With John Kirby Sextet from summer 1944 until January 1945, Eddie Heywood, February until October 1945, then joined Count Basie. Left Basie in 1950. (ref. John Chilton). Message: I met Emmett Berry’s daughter Christina at the National Jazz Museum of Harlem a few years ago, seeking information about her father. I promised her a solography, it has taken some time, but here it is. Hopefully you are happy with this tribute to your father, Christina! 3 EMMETT BERRY SOLOGRAPHY FLETCHER HENDERSON & HIS ORCHESTRA NYC. -

The Choo Choo Jazzers and Similar Groups: a Musical And

The Choo Choo Jazzers and Similar Groups: A Musical and Discographical Reappraisal, Part Two By Bob Hitchens, with revised discographical information compiled and edited by Mark Berresford Correction to the preamble to Part 1 of this listing. The words “the late” in connection with Johnny Parth should be deleted. Happily Johnny is going well at around 85 years of age. My apologies for the mistake and for any upset caused. Bob H. Please see Part One (VJM 175) for index to abbreviations and reference sources. GLADYS MURRAY, Comedienne Acc. By Kansas Five Clementine Smith (vcl, comb and paper) acc by: poss Bubber Miley (t) unknown (tb) Bob Fuller (cl) Louis Hooper (p) Elmer Snowden (bj) New York, c. November 24, 1924 5740-5 EVERYBODY LOVES MY BABY (Williams - Palmer) Regal 9760-A Rust: LM? or BM,BF,LH,ES. B&GR: LM or BM??,BF,LH,ES. Kidd: u/k,BF,LH,u/k. Miley disco: BM,u/k (tb)BF,LH,ES. Rains: BM. May be pseudonym for Josie Miles. (David Evans, notes to Document DOCD5518) Miley disco emphasises that other commentators have missed the trombone. So did I. I don’t think BM is here but Rains implies that the label states Miley (VJM157). I agree with KBR and feel that this is the same team as the 21 Nov Edisons. JOSIE MILES – JAZZ CASPER Josie Miles, Billy Higgins [Jazz Casper] (vcl duet) acc by: Bubber Miley (t) Louis Hooper (p) Elmer Snowden (bj) New York, c. November 24, 1924 5741-1-2 LET'S AGREE TO DISAGREE (Smith - Durante) Ban 1499-A Rust: BM or LM,LH,ES.