Commercialism, Subsistence, and Competency on the Western Virginia Frontier, 1765--1800

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1997, Volume 92, Issue No. 2

i f of 5^1- 1-3^-7 Summer 1997 MARYLAND Historical Magazine TU THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY Founded 1844 Dennis A. Fiori, Director The Maryland Historical Magazine Robert I. Cottom, Editor Patricia Dockman Anderson, Associate Editor Donna B. Shear, Managing Editor Jeff Goldman, Photographer Angela Anthony, Robin Donaldson Coblentz, Christopher T.George, Jane Gushing Lange, and Robert W. Schoeberlein, Editorial Associates Regional Editors John B. Wiseman, Frostburg State University Jane G. Sween, Montgomery Gounty Historical Society Pegram Johnson III, Accoceek, Maryland Acting as an editorial board, the Publications Committee of the Maryland Historical Society oversees and supports the magazine staff. Members of the committee are: John W. Mitchell, Upper Marlboro; Trustee/Ghair Jean H. Baker, Goucher Gollege James H. Bready, Baltimore Sun Robert J. Brugger, The Johns Hopkins University Press Lois Green Garr, St. Mary's Gity Gommission Toby L. Ditz, The Johns Hopkins University Dennis A. Fiori, Maryland Historical Society, ex-officio David G. Fogle, University of Maryland Jack G. Goellner, Baltimore Averil Kadis, Enoch Pratt Free Library Roland G. McGonnell, Morgan State University Norvell E. Miller III, Baltimore Richard Striner, Washington Gollege John G. Van Osdell, Towson State University Alan R. Walden, WBAL, Baltimore Brian Weese, Bibelot, Inc., Pikesville Members Emeritus John Higham, The Johns Hopkins University Samuel Hopkins, Baltimore Gharles McG. Mathias, Ghevy Ghase The views and conclusions expressed in this magazine are those of the authors. The editors are responsible for the decision to make them public. ISSN 0025-4258 © 1997 by the Maryland Historical Society. Published as a benefit of membership in the Maryland Historical Society in March, June, September, and December. -

West Virginia and Regional History Collection Newsletter Twenty-Year Index, Volume 1-Volume 20, Spring 1985-Spring 2005 Anna M

West Virginia & Regional History Center University Libraries Newsletters 2012 West Virginia and Regional History Collection Newsletter Twenty-Year Index, Volume 1-Volume 20, Spring 1985-Spring 2005 Anna M. Schein Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/wvrhc-newsletters Part of the History Commons West Virginia and Regional History Collection Newsletter Twenty-Year Index Volume 1-Volume 20 Spring 1985-Spring 2005 Compiled by Anna M. Schein Morgantown, WV West Virginia and Regional History Collection West Virginia University Libraries 2012 1 Compiler’s Notes: Scope Note: This index includes articles and photographs only; listings of WVRHC staff, WVU Libraries Visiting Committee members, and selected new accessions have not been indexed. Publication and numbering notes: Vol. 12-v. 13, no. 1 not published. Issues for summer 1985 and fall 1985 lack volume numbering and are called: no. 2 and no.3 respectively. Citation Key: The volume designation ,“v.”, and the issue designation, “no.”, which appear on each issue of the Newsletter have been omitted from the index. 5:2(1989:summer)9 For issues which have a volume number and an issue number, the volume number appears to left of colon; the issue number appears to right of colon; the date of the issue appears in parentheses with the year separated from the season by a colon); the issue page number(s) appear to the right of the date of the issue. 2(1985:summer)1 For issues which lack volume numbering, the issue number appears alone to the left of the date of the issue. Abbreviations: COMER= College of Mineral and Energy Resources, West Virginia University HRS=Historical Records Survey US=United States WV=West Virginia WVRHC=West Virginia and Regional History Collection, West Virginia University Libraries WVU=West Virginia University 2 West Virginia and Regional History Collection Newsletter Index Volume 1-Volume 20 Spring 1985-Spring 2005 Compiled by Anna M. -

Health and History of the North Branch of the Potomac River

Health and History of the North Branch of the Potomac River North Fork Watershed Project/Friends of Blackwater MAY 2009 This report was made possible by a generous donation from the MARPAT Foundation. DRAFT 2 DRAFT TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF TABLES ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 TABLE OF Figures ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................................................ 6 THE UPPER NORTH BRANCH POTOMAC RIVER WATERSHED ................................................................................... 7 PART I ‐ General Information about the North Branch Potomac Watershed ........................................................... 8 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Geography and Geology of the Watershed Area ................................................................................................. 9 Demographics .................................................................................................................................................... 10 Land Use ............................................................................................................................................................ -

Indian Warfare, Household Competency, and the Settlement of the Western Virginia Frontier, 1749 to 1794

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2007 Indian warfare, household competency, and the settlement of the western Virginia frontier, 1749 to 1794 John M. Boback West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Boback, John M., "Indian warfare, household competency, and the settlement of the western Virginia frontier, 1749 to 1794" (2007). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 2566. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/2566 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Indian Warfare, Household Competency, and the Settlement of the Western Virginia Frontier, 1749 to 1794 John M. Boback Dissertation submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor -

Chronicles of Border Warfare.” the Modern Title Page and Verso Have Been Relocated to the End of the Text

Project Gutenberg's Chronicles of Border Warfare, by Alexander Scott Withers This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Chronicles of Border Warfare or, a History of the Settlement by the Whites, of North-Western Virginia, and of the Indian Wars and Massacres in that section of the Indian Wars and Massacres in that section of the State Author: Alexander Scott Withers Editor: Reuben Gold Thwaites Release Date: June 26, 2009 [EBook #29244] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CHRONICLES OF BORDER WARFARE *** Produced by Roger Frank, Mark C. Orton and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Transcriber’s Note This is a 1971 reprint edition of the 1895 edition of “Chronicles of Border Warfare.” The modern title page and verso have been relocated to the end of the text. The 1895 edition includes and expands on the original 1831 edition. Throughout this text, the pagination of the original edition is indicated by brackets, such as [54]. Capitalization standards for the time (i.e. “fort Morgan,” “mrs. Pindall,” “Ohio river”) have been preserved. Variable hyphenation has been preserved. Archaic and variable spelling has been preserved. Author’s punctuation style has been preserved. Typographical problems have been corrected as listed in the Transcriber’s Note at the end of the text. -

Rethinking Religion in the Appalachian Mountains

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2014 The Rail and the Cross in West Virginia Timber Country: Rethinking Religion in the Appalachian Mountains Joseph F. Super Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Super, Joseph F., "The Rail and the Cross in West Virginia Timber Country: Rethinking Religion in the Appalachian Mountains" (2014). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6744. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6744 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rail and the Cross in West Virginia Timber Country: Rethinking Religion in the Appalachian Mountains Joseph F. Super Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Kenneth Fones-Wolf, Ph.D., Chair Elizabeth Fones-Wolf, Ph.D. Brian Luskey, Ph.D. Krystal Frazier, Ph.D. Jane Donovan, D. -

Washington County Historical Society

WASHINGTON COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY A PARTIAL HISTORY OF THE GREATHOUSE FAMILY IN AMERICA Author JACK MURRAY GREATHOUSE Number 7 in the Bulletin Series published by the Washington County Historical Society Fayetteville, Arkansas 1954 W. J. Lemke, editor THOSE WHO DO NOT LOOK UPON THEMSELVES AS A LINK CONNECTING THE PAST WITH THE FUTURE DO NOT PERFORM THEIR DUTY TO THE WORLD. (Daniel Webster) A MAN WHO IS NOT PROUD OF HIS ANCESTRY WILL NEVER LEAVE ANYTHING FOR WHICH HIS POSTERITY MAY BE PROUD OF HIM. (Edmund Burke) DEDICATION to ROBERT AMBROSE GREATHOUSE 1826 – 1911 FOREWORD In my youthful days my grandfather, to whom this book is dedicated, was a member of the Populist Party and a great admirer of Tom Watson, its leader. He was also at various times a Whig, a Know Nothing, and a Democrat, but never a Republican. He was a subscriber to Mr. Watson’s magazine and when he visited in my father’s home, one of my allotted tasks was to read to him, from cover to cover, each issue. Invariably he would fall asleep during the process and, when awakened, would always swear by all that is holy that he hadn’t been asleep and that he had heard every word. On one occasion, after nudging him awake and being tired of reading, I asked the question, “Grandpa, what was your Grandpa’s name?” His answer was “Gabriel”. The name Gabriel seems to have stuck in my mind throughout the years. This incident, together with a remark I once heard my father make ( that he was a member of one of the oldest Arkansas families ), was to a great extent the motivating influence which, almost a half century later, prompted me to attempt the compilation of a family history. -

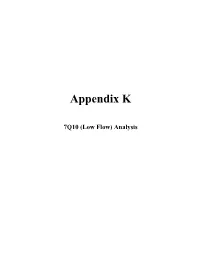

7Q10 Analysis Chart for Report

Appendix K 7Q10 (Low Flow) Analysis Appendix K: 7Q10 Analysis 7Q10 MINUS AVERAGE DAILY 7Q10 DAILY DAILY MAXIMUM 7Q10 IN MINUS MAXIMUM REPORTED DECIMAL DECIMAL FACILITY NAME COUNTY POTENTIAL 7Q10 GALLONS COMMENT AVERAGE SOURCE POTENTIAL FLOW LATITUDE LONGITUDE TO PER DAY DAILY TO FROM WITHDRAW FLOW WITHDRAW SURVEY AGGREGATES QUARRY RANDOLPH 80,809 2.2870 1,478,024 1,397,215 TYGART RIVER 38.92666667 -79.90861111 ALBRIGHT POWER STATION PRESTON 248,300,000 22.5000 14,541,120 -233,758,880 1,813 14,539,307 CHEAT RIVER 39.48944444 -79.63611111 GREENBRIER RIVER AT ALDERSON WATER TREATMENT PLANT GREENBRIER 900000 12.0630 7,795,979 6,895,979 ALDERSON WV Incorrect lat. ALEX ENERGY SURFACE MINES NICHOLAS 410,400 0.0030 1,939 -408,461 and long.? TWENTY MILE CREEK 38.30027778 -81.02027778 ROBINSON FORK OF ALEX ENERGY SURFACE MINES NICHOLAS 410,400 0.0050 3,231 -407,169 42,815 -39,584 TWENTY MILE CREEK 38.32166667 -80.98194444 AMERICAN FIBER RESOURCES MARION 8,640,000 340.0000 219,732,480 211,092,480 MONONGAHELA RIVER 39.52472222 -80.12777778 EAST FORK TWELVEPOLE ARGUS ENERGY, KIAH CREEK OPERATION WAYNE 396,000 0.1920 124,084 -271,916 69,523 54,561 CREEK 38.02777778 -82.29055556 ARMSTRONG PSD FAYETTE 216,632 1,890.0000 1,221,454,080 1,221,237,448 KANAWHA RIVER BANDMILL PREPARATION PLANT LOGAN 63,000 0.1600 103,404 40,404 RUM CREEK 37.81138889 -81.87111111 BAYER CROPSCIENCE LP, INSTITUTE PLANT KANAWHA 411,120,000 1,980.0000 1,279,618,560 868,498,560 KANAWHA RIVER 38.38 -81.78 BAYER CROPSCIENCE LP, INSTITUTE PLANT KANAWHA 411,120,000 1,980.0000 1,279,618,560 -

West Virginia Resources

Family History Sources in West Virginia the Mountain State Resources West Virginia History The part of Virginia that would later became West Virginia was unknown to the adventurers who settled Jamestown in 1607. With the exception of a few scattered frontier outposts and even fewer permanent settlements, the area remained Native American hunting and battlegrounds until well into the 1700s. While eastern tidewater counties of Virginia were settled by English aristocrats and their descendants, pioneers in western Virginia were generally perceived as a ragtag group from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and other parts of Virginia. The 1790 census lists more than 55,000 residents, of whom about 15,000 were of German descent. English immigrants and their descendants settled in Greenbrier, Library of Congress, “…Miners going into mine 7 A.M Boy beginning New, Kanawha, and Monongahela valleys, career as “picker,” color digital print from black and white negative. while Scots-Irish settlers made their homes in less accessible areas. Less than one percent of the population in 1790 was enslaved. After the Civil War, African Americans from Southern states moved into West Virginia seeking work in the railroads, mines, and industry. When Virginia seceded from the Union in 1861 at the start of the Civil War, the majority of those in western parts of the state opposed secession. A series of conventions were held, beginning in 1861, to determine western Virginia's fate. In order to become a new state, approval was required by the states concerned and Congress. The Virginia state government was reorganized on the grounds that the Secession Convention, convened without the consent of the people was invalid and secessionists were no longer entitled to office. -

In Western Maryland

• Free in store consultation • We recommend quantities needed and suggest varieties for your budget • Largest selection of Beer, Craft Beer, Kegs, Wine, Liquor, and Cigars in the area • We accept returns* and free delivery • Large quantity discounts on your favorite brands • Large variety of gifts available for your wedding party McHenry Beverage Shoppe 24465 Garrett Hwy., McHenry, MD 21541 301-387-5518 1-800-495-5518 www.mchenrybeverageshoppe.com Wedding Cakes, Pies, Cupcakes, Cookies, and special occasion cakes are available from Mountain Flour Bakery 24586 Garrett Hwy., McHenry, MD 21541 301-387-4075 240-442-5354 www.mountainflourbakery.com *Spirit returns can only be accepted if product is unfit for consumption, beverages that have been chilled cannot be accepted for returns. Products pruchased in error can be returned. M O U N T A I N D I S C O V E R I E S 3 Winter Hours: Rt. 219 – McHenry, Maryland – Deep Creek Lake Arcade Open Year Round Go Carts & Mini Golf September thru May: Friday, Saturday, Sunday Available Weather Permitting Summer Hours: 7 Days a Week SEE WEBSITE FOR HOURS 301-387-6268 deepcreekfunland.com 4 M O U N T A I N D I S C O V E R I E S ® MountainFALL/ W INTERDiscoveries 2019 In This Issue Lefty Grove Park Completed ..........................................5 Mountain Discoveries is a FREE publication printed twice yearly – Spring/Summer and 52nd Annual Autumn Glory Festival .............................. 6 Fall/Winter. Mountain Discoveries is focused on the Western Maryland region including Air Force One & Air Force Two ”SAM Fox” Travel .......10 neighboring Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Virginia. -

First Baptist Church Barnett Hospital and Nursing School

Surveyed Sites A number of sites with significance to the African American experience in Cabell County were identified through research and interaction with local residents and other informants. These sites are described in the following paragraphs. This is not an all-inclusive list of important African American sites, as further research should be undertaken to reveal other buildings and landscapes that have impacted the African American experience in the county. The general locations of the sites examined in greater detail are indicated on Figure 13. Barboursville Colored School 1125 Huntington Avenue, Barboursville. The town of Barboursville served as Cabell County’s seat of government prior to its removal to the expanding city of Huntington in 1887. Barboursville and Guyandotte were both early communities in the county. The Barboursville Colored School serves as a physical reminder of the segregated educational practices of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Description. The former Barboursville Colored School is located at 1125 Huntington Avenue, Barboursville, West Virginia (Figure 14). The Cabell County Assessor’s Office indicates that the structure was constructed circa 1900. The former school building, oriented to the east, is currently utilized as a residence. The single-story, one-bay (d), frame, hip-roof building exhibits a number of alterations that have taken place over the years, although its basic schoolhouse form is still recognizable (Figure 15). The central, single-leaf entry is filled with a replacement metal, single-light door. The area immediately surrounding the entry, which may have had sidelights, has been encased in vinyl siding. The entry is sheltered by a hip-roof porch supported by replacement metal columns. -

Final Environmental Assessment for Dam Modifications on the West Fork River Harrison County, West Virginia

Final Environmental Assessment for Dam Modifications on the West Fork River Harrison County, West Virginia REPORT PREPARED BY: USDA NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION SERVICE IN COOPERATION WITH U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE FOR THE: City of Clarksburg, WV - Clarksburg Water Board November 2010 November 2010 2 FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR DAM MODIFICATIONS ON THE WEST FORK RIVER Harrison County, West Virginia West Virginia Second Congressional District Responsible Federal Agency: United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service Local Sponsor: Clarksburg Water Board Cooperating Agency: US Fish and Wildlife Service Project Location: Harrison County, West Virginia For More Information: State Conservationist USDA – Natural Resources Conservation Service 75 High Street, Room 301 Morgantown, WV 26505 Phone: (304) 284-7540 Fax: (304) 284-4839 or Project Leader West Virginia Field Office U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 694 Beverly Pike Elkins, WV 26241 Phone: 304 636 6586 Fax: (304) 636 7824 Environmental Assessment Designation: FINAL Abstract: This Final Environmental Assessment describes the anticipated effects of removing three obsolete run- of-the-river water supply dams and modification of a fourth dam with an aquatic life passage structure in the West Fork River. This project proposes to restore, to the greatest extent possible, the aquatic and ecological integrity of at least forty miles of the West Fork River and many more miles of adjoining tributaries. This project has the potential to restore more suitable habitat for as many as twenty-five species of freshwater mussels including two federally listed species. Liability to the dam’s owners, the Clarksburg Water Board, will be substantially reduced with implementation of the recommended alternative.