Charles Johnson Maynard: the Enigmatic Naturalist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bird Observer

Bird Observer VOLUME 39, NUMBER 6 DECEMBER 2011 HOT BIRDS October 20, 2011, was the first day of the Nantucket Birding Festival, and it started out with a bang. Jeff Carlson spotted a Magnificent Frigatebird (right) over Nantucket Harbor and Vern Laux nailed this photo. Nantucket Birding Festival, day 2, and Simon Perkins took this photo of a Scissor-tailed Flycatcher (left). Nantucket Birding Festival, day 3, and Peter Trimble took this photograph of a Townsend's Solitaire (right). Hmmm, maybe you should go to the island for that festival next year! Jim Sweeney was scanning the Ruddy Ducks on Manchester Reservoir when he picked out a drake Tufted Duck (left). Erik Nielsen took this photograph on October 23. Turners Falls is one of the best places in the state for migrating waterfowl and on October 26 James P. Smith discovered and photographed a Pink-footed Goose (right) there, only the fourth record for the state. CONTENTS BIRDING THE WRENTHAM DEVELOPMENT CENTER IN WINTER Eric LoPresti 313 STATE OF THE BIRDS: DOCUMENTING CHANGES IN MASSACHUSETTS BIRDLIFE Matt Kamm 320 COMMON EIDER DIE-OFFS ON CAPE COD: AN UPDATE Julie C. Ellis, Sarah Courchesne, and Chris Dwyer 323 GLOVER MORRILL ALLEN: ACCOMPLISHED SCIENTIST, TEACHER, AND FINE HUMAN BEING William E. Davis, Jr. 327 MANAGING CONFLICTS BETWEEN AGGRESSIVE HAWKS AND HUMANS Tom French and Norm Smith 338 FIELD NOTE Addendum to Turkey Vulture Nest Story (June 2011 Issue) Matt Kelly 347 ABOUT BOOKS The Pen is Mightier than the Bin Mark Lynch 348 BIRD SIGHTINGS July/August 2011 355 ABOUT THE COVER: Northern Cardinal William E. -

4 Bird Observer a Bimonthly Journal — to Enhance Understanding, Observation, and Enjoyment of Birds VOL

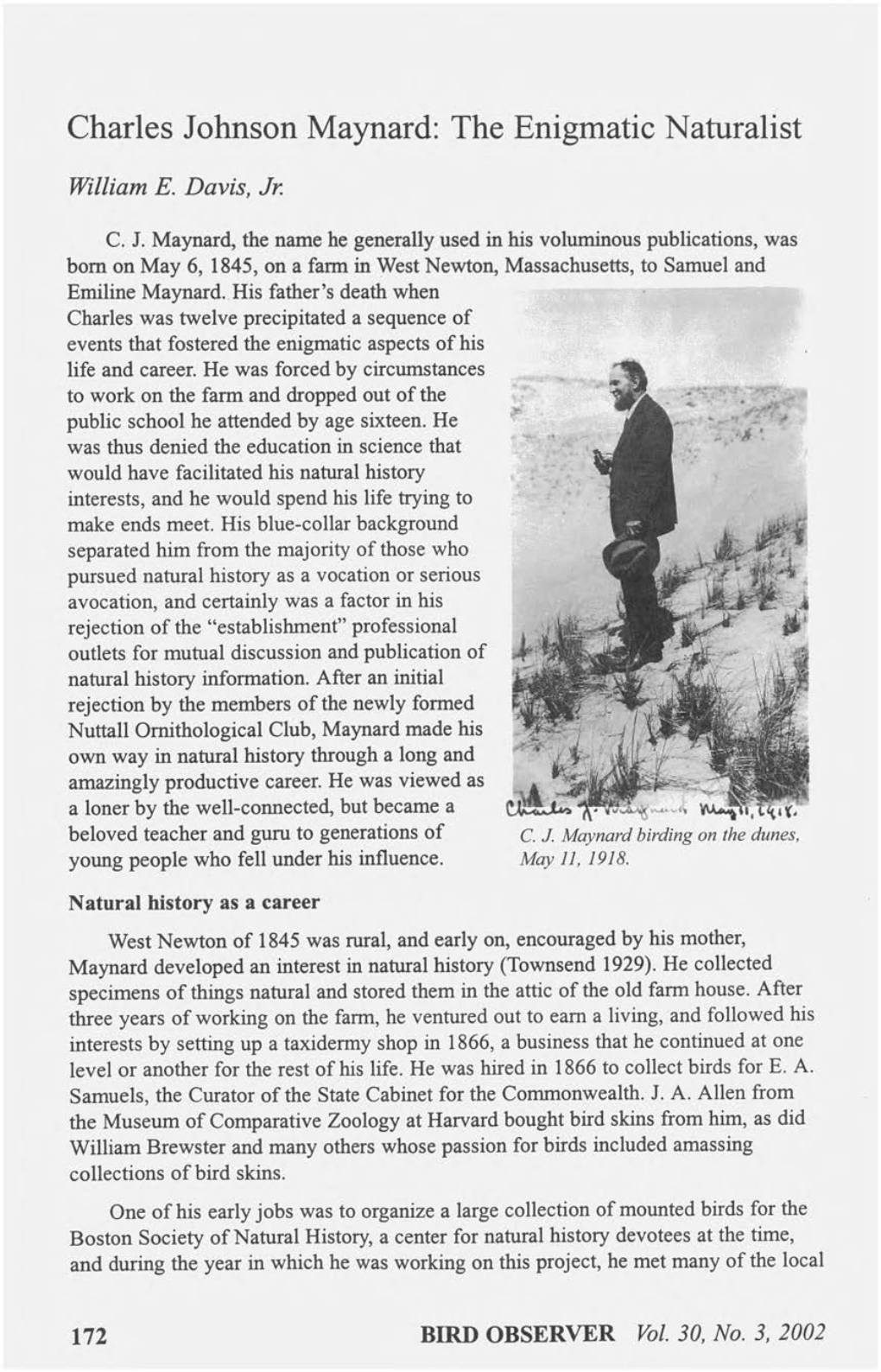

Bird Observer VOLUME 30, NUMBER 3 JUNE 2002 HOT BIRDS Part of an apparent regional influx of the species, this Barnacle Goose was found by Peter and Fay Vale in the Lyimfield ^1; Marshes on February 17. Maq Rines took this photo of the cooperative bird in Wakefield. pw* A Western Grebe, located by Rick Heil on March 6, was regularly seen north or south of parking lot 1 at Parker River National Wildlife Refuge into April. Steve Mirick took this digiscoped image on March 31. A flock of five Lesser Yellowlegs managed to over-winter in Newburyport Harbor. Phil Brown took this photo at Joppa Flats on March 25. Stan Bolton was birding in Westport when he found this handsome Harris’s Sparrow. Phil Brown took this image of the bird on April 1 (no fooling). K f On April 14, Leslie Bostrom saw a Common (Eurasian) Kestrel on Lieutenant’s Island, S. Wellfleet. On April 18, Bob Clem found what surely must have been the same bird at the Morris Island causeway in Chatham. Blair Nikula took this digiscoped image the same day. This bird stayed for weeks, and was visited by birders from across North America. CONTENTS B irding the Pondicherry W ildlife Refuge and V icinity Robert A. Quinn and David Govatski 153 Hybrid Terns Cryptically Similar to Forster’s Terns N esting i n M assachusetts Ian C. T. Nisbet 161 Charles Johnson Maynard: The Enigmatic N aturalist William E. Davis, Jr. 172 Summary of Leach’s Storm-petrel N esting on Penikese Island, M A , AND A R e p o r t o f P r o b a b l e N e s t i n g o n N o m a n ’ s L a n d I s l a n d Tom French 182 A dditional Significant Essex County N est Records from 2001 Jim Berry 188 Tree Swallow N esting Success at a Construction Site Richard Graefe 201 F i e l d N o t e s Birdsitting Joey Mason 208 A b o u t B o o k s Celebrating Biodiversity Brooke Stevens 212 B i r d S i g h t i n g s : January/February 2002 Summary 215 A b o u t t h e C o v e r : Blue-headed Vireo William E. -

Richard B. Primack

Richard B. Primack Department of Biology Boston University Boston, MA 02215 Contact information: Phone: 617-353-2454 Fax: 617-353-6340 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.bu.edu/biology/people/faculty/primack/ Lab Blog: http://primacklab.blogspot.com/ EDUCATION Ph.D. 1976, Duke University, Durham, NC Botany; Advisor: Prof. Janis Antonovics B.A. 1972, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA Biology; magna cum laude; Advisor: Prof. Carroll Wood EMPLOYMENT Boston University Professor (1991–present) Associate Professor (1985–1991) Assistant Professor (1978–1985) Associate Director of Environmental Studies (1996–1998) Faculty Associate: Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer Range Future Biological Conservation, an international journal. Editor (2004–present); Editor-in-Chief (2008-2016). POST-DOCTORAL, RESEARCH, AND SABBATICAL APPOINTMENTS Distinguished Overseas Professor of International Excellence, Northwest Forestry University, Harbin, China. (2014-2017). Visiting Scholar, Concord Museum, Concord, MA (2013) Visiting Professor, Tokyo University, Tokyo, Japan (2006–2007) Visiting Professor for short course, Charles University, Prague (2007) Putnam Fellow, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (2006–2007) Bullard Fellow, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (1999–2000) Visiting Researcher, Sarawak Forest Department, Sarawak, Malaysia (1980–1981, 1985– 1990, 1999-2000) Visiting Professor, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong (1999) Post-doctoral fellow, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (1980–1981). Advisor: Prof. Peter S. Ashton Post-doctoral fellow, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand (1976–1978). Advisor: Prof. David Lloyd 1 HONORS AND SERVICE Environmentalist of the Year Award. Newton Conservators for efforts to protect the Webster Woods. Newton, MA. (2020). George Mercer Award. Awarded by the Ecological Society of America for excellence in a recent research paper lead by a young scientist. -

Bibliography of North American Minor Natural History Serials in the University of Michigan Libraries

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF NORTH AMERICAN MINOR NATURAL HISTORY SERIALS IN THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN LIBRARIES BY MARGARET HANSELMAN UNDERWOOD Anm Arbor llniversity of Michigan Press 1954 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF NORTH AMERICAN MINOR NATURAL HISTORY SERIALS IN THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN LIBRARIES BY MARGARET HANSELMAN UNDERWOOD Anm Arbor University of Michigan Press 1954 my Aunts ELLA JANE CRANDELL BAILEY - ARABELLA CRANDELL YAGER and my daughter ELIZABETH JANE UNDERWOOD FOREWORD In this work Mrs. Underwood has made an important contribution to the reference literature of the natural sciences. While she was on the staff of the University of Michigan Museums library, she had early brought to her attention the need for preserving vanishing data of the distribu- tion of plants and animals before the territories of the forms were modified by the spread of civilization, and she became impressed with the fact that valuable records were contained in short-lived publications of limited circulation. The studies of the systematists and geographers will be facilitated by this bibliography, the result of years of painstaking investigation. Alexander Grant Ruthven President Emeritus, University of Michigan PREFACE Since Mr. Frank L. Burns published A Bibliography of Scarce and Out of Print North American Amateur and Trade Periodicals Devoted More or Less to Ornithology (1915) very little has been published on this sub- ject. The present bibliography includes only North American minor natural history serials in the libraries of the University of Michigan. University publications were not as a general rule included, and no attempt was made to include all of the publications of State Conserva- tion Departments or National Parks. -

Taxa of Charles Johnson Maynard and Their Type Specimens

THE CERION (MOLLUSCA: GASTROPODA: PULMONATA: CERIONIDAE) TAXA OF CHARLES JOHNSON MAYNARD AND THEIR TYPE SPECIMENS M. G. HARASEWYCH,' ADAM J. BALDINGER: YOLANDA VILLACAMPA,' AND PAUL GREENHALL' ABSTRACT. Charles Johnson Maynard (1845-1929) INTRODUCTION was a self-educated naturalist, teacher, and dealer in natural histOlY specimens and materials who con The family Cerionidae comprises a ducted extensive field work throughout FIOlida, the group of terrestrial pulmonate gastropods Bahamas, and the Cayman Islands. He published that are endemic to the tropical western prolifically on the fauna, flora, and anthropology of these areas. His publications included descriptions of Atlantic, ranging from southern Florida 248 of the 587 validly proposed species-level taxa throughout the Bahamas, Greater Antilles, within Cerionidae, a family of terrestrial gastropods Cayman Islands, western Virgin Islands, endemic to the islands of the tropical western Atlan and the Dutch Antilles, but are absent in tic. After his death, his collection of Cerionidae was purchased jOintly by tlle Museum of Comparative Zoo Jamaica, the Lesser Antilles, and coastal ology (MCZ) and the United States National Muse· Central and South America. These snails um, with the presumed primmy types remaining at are halophilic, occurring on terrestrial veg the MCZ and the remainder of the collection divided etation' generally witllin 100 m of the between these two museums and a few other insti shore, but occasionally 1 km or more from tutions. In this work, we provide 1) a revised collation of Maynard's publications dealing with Cerionidae, 2) the sea, presumably in areas where salt a chronological listing of species-level taxa proposed spray can reach them from one or more in these works, 3) a determination of the number and directions (Clench, 1957: 121). -

History of the Natural History of Sable Island

Proceedings of the Nova Scotian Institute of Science (2016) Volume 48, Part 2, pp. 351-366 HISTORY OF THE NATURAL HISTORY OF SABLE ISLAND IAN A. MCLAREN* Department of Biology, Dalhousie University Halifax, NS B3H 4J1 Documenting of natural history flourished with exploration of remote parts of North America during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, but the earliest published observations on the biota of Sable Island, along with casual observations in the journals of successive superintendents are vague, and emphasize exploitability. John Gilpin’s 1854 and 1855 visits were the first by a knowledgeable naturalist. His published 1859 “lecture” includes sketchy descriptions of the flora, birds, pinnipeds, and a list of collected marine molluscs. Reflecting growth of ‘cabinet’ natural history in New England, J. W. Maynard in 1868 collected a migrant sparrow in coastal Massachusetts, soon named Ipswich Sparrow and recognized as nesting on Sable Island. This persuaded New York naturalist Jonathan Dwight to visit the island in June-July1894 and produce a substantial monograph on the sparrow. He in turn encouraged Superintendent Bouteiller’s family to send him many bird specimens, some very unusual, now in the American Museum of Natural History. Dominion Botanist John Macoun made the first extensive collection of the island’s plants in 1899, but only wrote a casual account of the biota. He possibly also promoted the futile tree-planting experiment in May 1901 directed by William Saunders, whose son, W. E., published some observations on the island’s birds, and further encouraged the Bouteillers to make and publish systematic bird observations, 1901- 1907. -

Back of Beyond Books, ABAA 83 N

Back of Beyond Books Catalogue No. 15 25th Anniversary 1990 - 2015 1 Back of Beyond Books Rare Book Catalogue No. 15 - August 2015 Back of Beyond Books celebrates our 25th anniversary this year with our largest cata- logue to date. With over 300 items to choose from, we’ve tried to represent the several genres we specialize in yet include a curated potpourri of relevant fun material. The name “Back of Beyond” is taken from Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang. Abbey spent much time in and around Moab. Upon his passing in early 1989, a memorial was held outside Arches National Park and attended by several hundred friends and admirers. At some point during this gathering, the idea of a bookstore to honor Ed’s legacy was germinated. Nine months later the doors opened at 83 N. Main Street in Moab. I purchased the store in August 2004, opening up a rare book corner soon after. In celebration, we proudly announce the publication in facsimile of the manuscript of a speech Ed gave at the University of Montana on April 1, 1985. Dead Horses & Sakred Kows was later published as The Cowboy and His Cow, with numerous changes. The manuscript is filled with Ed’s annotations and deletions and serves as a benchmark to the actual speech Ed presented that night. There are relatively few Abbey manuscripts outside of the University of Arizona Special Collections and we thank Clarke Abbey for this privilege. Brooke Williams has penned an orig- inal essay and Dave Wilder has contributed artwork inspired by Abbey. -

Richard B. Primack

Richard B. Primack Department of Biology Boston University Boston, MA 02215 Contact information: Phone: 617-353-2454 Fax: 617-353-6340 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.bu.edu/biology/people/faculty/primack/ Lab Blog: http://primacklab.blogspot.com/ EDUCATION Ph.D. 1976, Duke University, Durham, NC Botany; Advisor: Prof. Janis Antonovics B.A. 1972, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA Biology; magna cum laude; Advisor: Prof. Carroll Wood EMPLOYMENT Boston University Professor (1991–present) Associate Professor (1985–1991) Assistant Professor (1978–1985) Associate Director of Environmental Studies (1996–1998) Faculty Associate: Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer Range Future Biological Conservation, an international journal. Editor (2004–present); Editor-in-Chief (2008-2016). POST-DOCTORAL, RESEARCH, AND SABBATICAL APPOINTMENTS Distinguished Overseas Professor of International Excellence, Northwest Forestry University, Harbin, China. (2014-2017). Visiting Scholar, Concord Museum, Concord, MA (2013) Visiting Professor, Tokyo University, Tokyo, Japan (2006–2007) Visiting Professor for short course, Charles University, Prague (2007) Putnam Fellow, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (2006–2007) Bullard Fellow, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (1999–2000) Visiting Researcher, Sarawak Forest Department, Sarawak, Malaysia (1980–1981, 1985– 1990, 1999-2000) Visiting Professor, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong (1999) Post-doctoral fellow, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (1980–1981). Advisor: Prof. Peter S. Ashton Post-doctoral -

In Memoriam: Charles Foster Batchelder

•958a 15 IN MEMORIAM: CHARLES FOSTER BATCHELDER BY WENDELL TABER CHARLES FOSTER BATCHELDER,last of the Founders of the American Ornithologists'Union and its eighth President(1905-1908), died at the age of 98 in his home in Peterborough,New Hampshire, on November 7, 1954. He had never taken out life insurance. Drily, he would remark he had figuredhe could beat the game. He failed, though, to achieve a minor goal, a life span of one hundred years. He had attained, easily, his major aim, the title of SeniorGraduate of Harvard College. In 1953, when Nathan M. Puseywas celebratinghis own "25th." and in process of being installedas Presidentof Harvard University, Batcheldermight well have led the parade of graduates at Commencement--in a wheel chair•elebrating his "Diamond Reunion"--alone! He refused. "Merely an object of curiosity." was his comment. His parents, Francis Lowell Batchelder and Susan Cabot Foster Batchelder,had acquireda country estate at 7 Kirkland Street in Cam- bridge, Massachusetts. Here, directly oppositethe back side of Hol- worthy Hall in the Harvard Yard, Batchelder was born, grew up, and resided for some months in winter for the rest of his life. Here, for about thirty years following the death of William Brewster, met the Nuttall OrnithologicalClub. Batchelder, born July 20, 1856, hardly knew his father, who died when Batchelderwas barely eighteenmonths of age. Ever an out-door lad as he grew up, he often wanderedover the four miles or so to the little hamlet of Arlington, riding in due time one of those huge wheels with baby trailer-wheel which precededthe bicycle as we know it today. -

Bird Observer

Bird Observer VOLUME 39, NUMBER 1 FEBRUARY 2011 HOT BIRDS On November 3, 2010, a Black-chinned Hummingbird (left) appeared at a feeder in Siasconset, Nantucket. On November 11, Edie Ray took this photograph of the perched bird. Amazingly, another Black- chinned appeared at the same place in November 2007! On November 6, Jim Sweeney discovered and photographed a first-year Harris’s Sparrow (right) in the Burrage Pond WMA in Halifax. While checking the thickets in Squantum on November 6, Ronnie Donovan discovered a Boreal Chickadee (left) among a flock of Black-caps. On October 9, Ryan Schain took this photograph. Classic Patagonia Picnic Table Effect: While looking for the Boreal Chickadee on November 11, Chris Floyd discovered a Le Conte’s Sparrow (right) in Squantum. Jeremiah Trimble photographed it the same day. George Gove and Judy Gordon found this Pink-footed Goose (left) on Concord Road in Sudbury on November 17. Jeremiah Trimble took this photograph later that day. CONTENTS SPRING BIRDING IN COLD SPRING PARK Maurice (Pete) Gilmore 5 2003 BOUCHARD OIL SPILL: IMPACT ON PIPING PLOVERS Jamie Bogart 12 GEEZER BIRDING John Nelson 16 POPULATION STATUS OF THE OSPREY IN ESSEX COUNTY, MASSACHUSETTS David Rimmer and Jim Berry 20 AMERICAN KESTREL NEST BOXES Art Gingert 25 FIELD NOTES Discovery of a Brood Patch on an Adult Male American Goldfinch (Carduelis tristis) Sue Finnegan 32 Chuck-will’s-widow Heard in Broad Daylight John Galluzzo 34 ABOUT BOOKS The Serial Fabulist of Ornithology Mark Lynch 36 BIRD SIGHTINGS September/October 2010 43 ABOUT THE COVER: Northern Flicker William E. -

In the Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht) Cerion

STUDIES ON THE FAUNA OF CURAÇAO AND OTHER CARIBBEAN ISLANDS: No. 187 Caribbean land molluscs: Cerion in the Cayman Islands by P. Wagenaar Hummelinck (Zoologisch Laboratorium. Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht) Summary 1 INTRODUCTION - Figs. 1-4 3 Maynard's species (Table 1) - Figs. 5-7; PI. IX 11 LOCALITIESAND OCCURRENCE - Figs. 8-22; Pis. I—VIII 20 Measurements (Tables 2-4) 42 GRAND CAYMAN 46 LITTLE CAYMAN 47 CAYMAN BRAC 48 SYNOPSIS AND KEY (Tables 5-6) 49 - IX-XVIII NOTES ON THE SPECIES Pis. 54 Cerion martinianum • (Kiister) - Figs. 23-24 54 Cerion nanus(Maynard) 56 Cerion pannosum (Maynard) 57 Cerion copium (Maynard) 59 Cerion caymanicolum sp. n 65 REFERENCES 66 Summary This ofthe situation of Cerion in the with paper presents a survey present Cayman Islands, reference the revealed CH. J. MAYNARD’S of the Stro- to problems by “Monograph genus 1889. This be of interest to taxonomists who would like in phia”, may to investigate a in which fail. “modern way” a species complex any “biological species concept” appears to 2 The study is based on material collected in Grand Cayman, Little Cayman and CaymanBrac, from May 16 until June 12, 1973. CLENCH (1964) considers the names of all 14 species described by MAYNARD from Little Brac Cayman and Cayman to be synonyms of Cerion pannosum (Maynard), with the exception of Strophiananawhich he accepts as Cerion nanus(Maynard). While agreeingwith CLENCH as regards the status of Strophia nana, the author hesitates to lump together all MAYNARDS other species but considers that at least two variable and intergradinggroups of Cerion (= Strophia) should be distinguished: C. -

Bird Sightings Robert H

Bird Observer VOLUME 30, NUMBER 6 DECEMBER 2002 30th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE HOT BIRDS A Selasphorus hummingbird bonanza occurred this autumn, with at least eight birds being reported at feeders across the state. Phil Brown took these photographs of a Rufous/Allen’s Hummingbird in Essex in late September (left) and a female Rufous Hummingbird in Amherst in October (right). A> /t A Yellow-headed Blackbird was a Bob Packard found a Cassin’s welcome sight at the feeding station Kingbird in Whatley on November at Mass Audubon’s Wellfleet Bay 1, and Denny Abbot was there to get Sanctuary. David Larson took this this dramatic flight shot the next day. shot of the immature male on October 14. On November 7, Rick Heil found a Hot Birds rarely features images of Barnacle Goose in Ispwich. David captive birds, but this stunning photo of a Larson took this photograph of the Varied Thrush, netted and banded at rather unapproachable bird. Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences on November 8, is way too nice to pass up. CONTENTS A D i f f e r e n t K i n d o f W h e r e - t o - g o -B i r d i n g : T e n F a v o r i t e P l a c e s O F TH E Bird Observer S t a f f 382 B e s t B i r d s i n M assachusetts : 1993-2002 Wayne R. Petersen 395 A V i s i t o r f r o m t h e F a r N o r t h R e t u r n s Norman Smith 399 F i e l d N o t e s Great Gray Owl Mark Wilson 407 The Last Heath Hen: A Story Never Before Told Vineyard Gazette 408 A S u r v e y o f P u b l i s h e d B i r d R e c o r d s i n N e w E n g l a n d Jim Berry 410 W r e n Q u e s t Robert H.