4 Bird Observer a Bimonthly Journal — to Enhance Understanding, Observation, and Enjoyment of Birds VOL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ipswich Where to Go • What to See • What to Do

FINAL-1 Wed, Jun 21, 2017 8:03:55 PM DESTINATION IPSWICH WHERE TO GO • WHAT TO SEE • WHAT TO DO Nicole Goodhue Boyd Nicole The Salem News PHOTO/ FINAL-1 Wed, Jun 21, 2017 8:03:57 PM S2 • Friday, June 23, 2017 June • Friday, DESTINATION IPSWICH DESTINATION Trust in Our Family Business The Salem News • News Salem The Marcorelle’s Fine Wine, Liquor & Beer Specializing in beverage catering, functions and delivery since 1935. 30 Central Street, Ipswich, MA 01938, Phone: 978-356-5400 Proud retailer of Ipswich Ale Brewery products Visit ipswichalebrewery.com for brewery tour & restaurant hours. FINAL-1 Wed, Jun 21, 2017 8:03:58 PM S3 The Salem News • News Salem The Family Owned & Operated Since 1922 IPSWICH DESTINATION • Send someone flowers, make someone happy • Colorful Hanging Baskets and 23, 2017 June • Friday, colorful flowering plants for all summer beauty • Annuals and Perennials galore • Fun selection of quality succulents & air plants • Walk in cut flower cooler • Creative Floral Arrangements • One of a Kind Gifts & Cards Friend us on www.gordonblooms.com 24 Essex Rd. l Ipswich, MA l 978.356.2955 FINAL-1 Wed, Jun 21, 2017 8:03:58 PM S4 RECREATION • Friday, June 23, 2017 June • Friday, DESTINATION IPSWICH DESTINATION The Salem News • News Salem The File photos The rooftop views from the Great House at the Crane Estate Crane Beach is one of the most popular go-to spots for playing on the sand and in the water. include the “allee” that leads to the Atlantic Ocean. Explore the sprawling waterways and trails Visitors looking to get through the end of October. -

Bird Observer

Bird Observer VOLUME 39, NUMBER 6 DECEMBER 2011 HOT BIRDS October 20, 2011, was the first day of the Nantucket Birding Festival, and it started out with a bang. Jeff Carlson spotted a Magnificent Frigatebird (right) over Nantucket Harbor and Vern Laux nailed this photo. Nantucket Birding Festival, day 2, and Simon Perkins took this photo of a Scissor-tailed Flycatcher (left). Nantucket Birding Festival, day 3, and Peter Trimble took this photograph of a Townsend's Solitaire (right). Hmmm, maybe you should go to the island for that festival next year! Jim Sweeney was scanning the Ruddy Ducks on Manchester Reservoir when he picked out a drake Tufted Duck (left). Erik Nielsen took this photograph on October 23. Turners Falls is one of the best places in the state for migrating waterfowl and on October 26 James P. Smith discovered and photographed a Pink-footed Goose (right) there, only the fourth record for the state. CONTENTS BIRDING THE WRENTHAM DEVELOPMENT CENTER IN WINTER Eric LoPresti 313 STATE OF THE BIRDS: DOCUMENTING CHANGES IN MASSACHUSETTS BIRDLIFE Matt Kamm 320 COMMON EIDER DIE-OFFS ON CAPE COD: AN UPDATE Julie C. Ellis, Sarah Courchesne, and Chris Dwyer 323 GLOVER MORRILL ALLEN: ACCOMPLISHED SCIENTIST, TEACHER, AND FINE HUMAN BEING William E. Davis, Jr. 327 MANAGING CONFLICTS BETWEEN AGGRESSIVE HAWKS AND HUMANS Tom French and Norm Smith 338 FIELD NOTE Addendum to Turkey Vulture Nest Story (June 2011 Issue) Matt Kelly 347 ABOUT BOOKS The Pen is Mightier than the Bin Mark Lynch 348 BIRD SIGHTINGS July/August 2011 355 ABOUT THE COVER: Northern Cardinal William E. -

Richard B. Primack

Richard B. Primack Department of Biology Boston University Boston, MA 02215 Contact information: Phone: 617-353-2454 Fax: 617-353-6340 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.bu.edu/biology/people/faculty/primack/ Lab Blog: http://primacklab.blogspot.com/ EDUCATION Ph.D. 1976, Duke University, Durham, NC Botany; Advisor: Prof. Janis Antonovics B.A. 1972, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA Biology; magna cum laude; Advisor: Prof. Carroll Wood EMPLOYMENT Boston University Professor (1991–present) Associate Professor (1985–1991) Assistant Professor (1978–1985) Associate Director of Environmental Studies (1996–1998) Faculty Associate: Pardee Center for the Study of the Longer Range Future Biological Conservation, an international journal. Editor (2004–present); Editor-in-Chief (2008-2016). POST-DOCTORAL, RESEARCH, AND SABBATICAL APPOINTMENTS Distinguished Overseas Professor of International Excellence, Northwest Forestry University, Harbin, China. (2014-2017). Visiting Scholar, Concord Museum, Concord, MA (2013) Visiting Professor, Tokyo University, Tokyo, Japan (2006–2007) Visiting Professor for short course, Charles University, Prague (2007) Putnam Fellow, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (2006–2007) Bullard Fellow, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (1999–2000) Visiting Researcher, Sarawak Forest Department, Sarawak, Malaysia (1980–1981, 1985– 1990, 1999-2000) Visiting Professor, University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong (1999) Post-doctoral fellow, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (1980–1981). Advisor: Prof. Peter S. Ashton Post-doctoral fellow, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand (1976–1978). Advisor: Prof. David Lloyd 1 HONORS AND SERVICE Environmentalist of the Year Award. Newton Conservators for efforts to protect the Webster Woods. Newton, MA. (2020). George Mercer Award. Awarded by the Ecological Society of America for excellence in a recent research paper lead by a young scientist. -

Climate Vulnerability Assessment Coastal Properties Trustees of Reservations

Climate Vulnerability Assessment Coastal Properties Trustees of Reservations Prepared For: Trustees of Reservations 200 High Street Boston, MA 02110 Prepared By: Woods Hole Group, Inc. A CLS Group Company 81 Technology Park Drive East Falmouth, MA 02536 October 2017 Climate Vulnerability Assessment Coastal Properties Trustees of Reservations October 2017 Prepared for: Trustees of Reservations 200 High Street Boston, MA 02110 Prepared by: Woods Hole Group 81 Technology Park Drive East Falmouth MA 02536 (508) 540-8080 “This document contains confidential information that is proprietary to the Woods Hole Group, Inc. Neither the entire document nor any of the information contained therein should be disclosed or reproduced in whole or in part, beyond the intended purpose of this submission without the express written consent of the Woods Hole Group, Inc.” Woods Hole Group, Inc. A CLS Group Company EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Conservation managers confront diverse and ever-changing threats to the properties they are charged with maintaining and protecting. Long term planning to sustainably manage and protect diverse assets for a wide range of uses is central to this mission. The Trustees of Reservations (Trustees) manages over 100 special places and 26,000 acres around Massachusetts (Trustees, 2014) . The properties they manage include more than 70 miles of coastline (Trustees, 2014), an area that is subject to climate driven changes in sea level, storm surge and inundation. From the Castle at Castle Hill to popular public beaches, cultural and historical points, rare and endangered species habitats, lighthouses and salt marshes, the Trustees oversee diverse assets. They are charged with managing these properties to conserve habitat, protect cultural resources and provide exciting and diverse educational and recreational activities for visitors. -

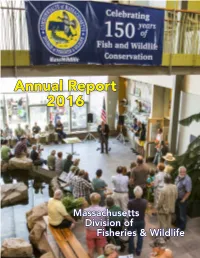

Annual Report 2016

Annual Report 2016 Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife 143 n Saturday June 4, 2016, Mass- OWildlife celebrated its 150th anniversary with an open house at the new Field Headquarters in Westborough. The event featured interactive displays, demonstra- tions, kids crafts, guided nature walks, live animals, and hands-on activities like archery, casting, and simulated target shooting, plus cake and a BBQ, and was attended by 1,000 people! 142 Table of Contents 2 The Board Reports 15 Fisheries 53 Wildlife 71 Private Lands Habitat Management 73 Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program 84 Information & Education 98 Hunter Education 100 District Reports 120 Wildlife Lands 129 Federal Aid 131 Personnel Report 136 Financial Report About the Cover: Mr. George L. Darey, Chairperson of the Fisheries & Wildlife Board, addresses a large crowd at MassWildlife’s 150th anniversary open house held at the division’s new field headquarters in Westborough. Photo by Troy Gipps/MassWildlife Back Cover: Participants in MassWildlife's 150th anniversary open house. Photos by Bill Byrne and Troy Gipps All photos by MassWildlife unless otherwise credited. Printed on Recycled Paper. 1 The Board Reports George L. Darey Chairperson Overview pediment to keeping high-quality staff and encouraging the promotion of section heads from within our own ranks, was The Massachusetts Fisheries and Wildlife Board consists of finally resolved in FY 2016 with across-the-board upgrades seven persons appointed by the Governor to 5-year terms. in Managers’ pay scales. This is a very welcome change, By law, the individuals appointed to the Board are volun- putting MassWildlife’s manager pay on a par with compa- teers, receiving no remuneration for their service to the rable management levels in other scientific state agencies, Commonwealth. -

Bibliography of North American Minor Natural History Serials in the University of Michigan Libraries

BIBLIOGRAPHY OF NORTH AMERICAN MINOR NATURAL HISTORY SERIALS IN THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN LIBRARIES BY MARGARET HANSELMAN UNDERWOOD Anm Arbor llniversity of Michigan Press 1954 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF NORTH AMERICAN MINOR NATURAL HISTORY SERIALS IN THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN LIBRARIES BY MARGARET HANSELMAN UNDERWOOD Anm Arbor University of Michigan Press 1954 my Aunts ELLA JANE CRANDELL BAILEY - ARABELLA CRANDELL YAGER and my daughter ELIZABETH JANE UNDERWOOD FOREWORD In this work Mrs. Underwood has made an important contribution to the reference literature of the natural sciences. While she was on the staff of the University of Michigan Museums library, she had early brought to her attention the need for preserving vanishing data of the distribu- tion of plants and animals before the territories of the forms were modified by the spread of civilization, and she became impressed with the fact that valuable records were contained in short-lived publications of limited circulation. The studies of the systematists and geographers will be facilitated by this bibliography, the result of years of painstaking investigation. Alexander Grant Ruthven President Emeritus, University of Michigan PREFACE Since Mr. Frank L. Burns published A Bibliography of Scarce and Out of Print North American Amateur and Trade Periodicals Devoted More or Less to Ornithology (1915) very little has been published on this sub- ject. The present bibliography includes only North American minor natural history serials in the libraries of the University of Michigan. University publications were not as a general rule included, and no attempt was made to include all of the publications of State Conserva- tion Departments or National Parks. -

Massachuse S Bu Erflies

Massachuses Bueries Spring 2015, No. 44 Massachusetts Butteries is the semiannual publication of the Massachusetts Buttery Club, a chapter of the North American Buttery Association. Membership in NABA-MBC brings you American Butteries and Buttery Gardener . If you live in the state of Massachusetts, you also receive Massachusetts Butteries , and our mailings of eld trips, meetings, and NABA Counts in Massachusetts. Out-of-state members of NABA-MBC who wish to receive Massachusetts Butteries may order it from our secretary for $7 per issue, including postage. Regular NABA dues are $35 for an individual, $45 for a fami ly, and $70 outside the United States. Send a check made out to NABA to: NABA, 4 Delaware Road, Morristown, NJ 07960. NABA-MASSACHUSETTS BUTTERFLY CLUB Ofcers President : Howard Hoople, 10 Torr Street, Andover, MA, 01810-4022. (978) 475-7719 [email protected] Vice President-East : Dawn Puliaco, 18 Irene Circle, Ashland, MA, 01721. (508) 881-0936 [email protected] Vice President-West : Tom Gagnon, 175 Ryan Road, Florence, MA, 01062. (413) 584-6353 [email protected] Treasurer : Elise Barry, 45 Keep Avenue, Paxton, MA, 01612-1037. (508) 795-1147 [email protected] Secretary : Barbara Volkle, 400 Hudson Street, Northboro, MA, 01532. (508) 393-9251 [email protected] Staff Editor, Massachusetts Butteries : Bill Benner, 53 Webber Road, West Whately, MA, 01039. (413) 320-4422 [email protected] Records Compiler : Mark Fairbrother, 129 Meadow Road, Montague, MA, 01351-9512. [email protected] Webmaster : Karl Barry, 45 Keep Avenue, Paxton, MA, 01612-1037. (508) 795-1147 [email protected] www.massbutteries.org Massachusetts Butteries No. -

Tara P. Marden, B.A., M.S. Senior Project Manager/Coastal Geologist

Tara P. Marden, B.A., M.S. Senior Project Manager/Coastal Geologist EXPERTISE Ms. Marden has 22 years of experience in the areas of coastal geology and coastal process evaluation. During the past five years, her focus at Woods Hole Group has been managing and implementing regional dredging and beach nourishment programs for local municipalities and private homeowners, often forging effective public‐private partnerships. Ms. Marden works closely with the clients, regulators and contractors to ensure that every facet of the project, from the initial site assessment through design and permitting and ultimately construction, is successfully and seamlessly Education implemented. Ms. Marden is also involved in long‐term monitoring for many 1999 – M.S. Geology of these projects. UNC at Wilmington During her tenure at Woods Hole Group, Ms. Marden has specialized in many projects related to tidal inlet and sediment transport processes, sand resource 1996 – B.A. Geology investigations for beach nourishment as well as design, permitting (local, Northeastern University state, and federal) and construction oversight for a myriad of coastal structure and bio‐engineered projects. She is experienced with all facets of Professional Affiliations environmental impact analyses, ranging from the collection of field data to Municipal Vulnerability engineering design, alternatives analyses, and design for mitigation. Ms. Preparedness Certified Marden also has experience in the use of GIS technology to display and Provider (MA MVP analyze spatially‐related data for coastal and marine mapping projects. Program) American Shore and Beach QUALIFICATION SUMMARY Preservation Association (ASBPA) 22 years experience in coastal and geologic processes evaluation. Specializes in managing and implementing multi‐faceted dredging and Publications & Presentations beach nourishment programs for local municipalities and private 50 homeowners. -

Taxa of Charles Johnson Maynard and Their Type Specimens

THE CERION (MOLLUSCA: GASTROPODA: PULMONATA: CERIONIDAE) TAXA OF CHARLES JOHNSON MAYNARD AND THEIR TYPE SPECIMENS M. G. HARASEWYCH,' ADAM J. BALDINGER: YOLANDA VILLACAMPA,' AND PAUL GREENHALL' ABSTRACT. Charles Johnson Maynard (1845-1929) INTRODUCTION was a self-educated naturalist, teacher, and dealer in natural histOlY specimens and materials who con The family Cerionidae comprises a ducted extensive field work throughout FIOlida, the group of terrestrial pulmonate gastropods Bahamas, and the Cayman Islands. He published that are endemic to the tropical western prolifically on the fauna, flora, and anthropology of these areas. His publications included descriptions of Atlantic, ranging from southern Florida 248 of the 587 validly proposed species-level taxa throughout the Bahamas, Greater Antilles, within Cerionidae, a family of terrestrial gastropods Cayman Islands, western Virgin Islands, endemic to the islands of the tropical western Atlan and the Dutch Antilles, but are absent in tic. After his death, his collection of Cerionidae was purchased jOintly by tlle Museum of Comparative Zoo Jamaica, the Lesser Antilles, and coastal ology (MCZ) and the United States National Muse· Central and South America. These snails um, with the presumed primmy types remaining at are halophilic, occurring on terrestrial veg the MCZ and the remainder of the collection divided etation' generally witllin 100 m of the between these two museums and a few other insti shore, but occasionally 1 km or more from tutions. In this work, we provide 1) a revised collation of Maynard's publications dealing with Cerionidae, 2) the sea, presumably in areas where salt a chronological listing of species-level taxa proposed spray can reach them from one or more in these works, 3) a determination of the number and directions (Clench, 1957: 121). -

Historic Properties Survey Plan January 2014

TOWN OF ESSEX Historic Properties Survey Plan January 2014 Prepared for the Essex Historical Commission Wendy Frontiero, Preservation Consultant Public Archaeology Laboratory, Inc. TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page Introduction 4 Overview of the Town of Essex 5 Essex Historical Commission 6 Components of Historic Preservation Planning 7 Preservation Planning Recommendations for Essex 13 Archaeological Summary 16 APPENDICES A Directory of Historic Properties Recommended for Further Survey B Prioritized List of Properties Recommended for Further Survey C Bibliography and References for Further Research D Preservation Planning Resources E Reconnaissance Survey Town Report for Essex. Massachusetts Historical Commission, 1985. F Essex Reconnaissance Report; Essex County Landscape Inventory; Massachusetts Heritage Landscape Inventory Program. Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation and Essex National Heritage Commission, 2005. Town of Essex - Historic Properties Survey Plan page 2 2014 1884 map of Essex (George H. Walker & Co.) Town of Essex - Historic Properties Survey Plan page 3 2014 INTRODUCTION This Historic Properties Survey Plan has been prepared for, and in cooperation with, the Essex Historical Commission. The Plan provides a guide for future updates and expansion of the town's existing inventory of cultural resources. It also recommends future survey-based activities to enhance the recognition, appreciation, and protection of historic properties in the town. Town of Essex - Historic Properties Survey Plan page 4 2014 OVERVIEW OF THE TOWN OF ESSEX The Town of Essex is located in the northeast portion of Essex County, situated on the Atlantic coast around the Essex River. Its population of just over 3,500 occupies an area of 15.9 square miles. -

North of Boston 2010-2011 Visitor Guide

Where to Eat, Stay, Shop & Play PLUS: FOUR SEASONS OF FUN GUIDE TO OUTDOOR ACTIVITIES ART, HISTORY & CULTURE LOCAL FARMERS MARKETS PULL OUT REGIONAL MAP 4 FOUR SEASONS OF FUN No matter the season, the 34 cities and towns of Essex County offer plenty for visitors and locals alike. So when is the best time to come? How about… now!. 14 EXPERIENCE THE GREAT OUTDOORS Discover the splendor of the North of Boston region by land The North of Boston Convention & Visitors or sea. Find sand-sational beaches and prime paths and parks Bureau proudly represents the thirty four for outdoor recreation. cities and towns of Essex County as a tourism destination. 15 BEST NORTH SHORE Beaches Amesbury, Andover, Beverly, Boxford, Danvers, Essex, Georgetown, Gloucester, 18 GUIDE to OUTDOOR ActiVITIES Groveland, Hamilton, Haverhill, Ipswich, Lawrence, Lynnfield, Lynn, 20 WHERE TO EAT AND SHOP Manchester, Marblehead, Merrimac, Essex County is home to some of the best restaurants and Methuen, Middleton, Nahant, Newbury, shops in the state. Here you’ll find unique shops, vibrant Newburyport, North Andover, Peabody, downtowns, and signature New England fare. Rockport, Rowley, Salem, Salisbury, Saugus, Swampscott, Topsfield, Wenham, West LOCAL FARMERS MARKETS Newbury 23 North of Boston CVB NORTH OF BOSTON EVENTS 10 State Street, Suite 309, 24 There are exhibits, festivals, sports & recreation, concerts, Newburyport, MA 01950 theatrical performances, and special dining events year round. 800-742-5306, 978-225-1559 Here are some highlights. Cover photo by Dale Blank: Family enters the boardwalk in the dunes and heads to the 26 ART & HISTORY INTERTWINE annual Sand Blast at scenic Crane Beach. -

History of the Natural History of Sable Island

Proceedings of the Nova Scotian Institute of Science (2016) Volume 48, Part 2, pp. 351-366 HISTORY OF THE NATURAL HISTORY OF SABLE ISLAND IAN A. MCLAREN* Department of Biology, Dalhousie University Halifax, NS B3H 4J1 Documenting of natural history flourished with exploration of remote parts of North America during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, but the earliest published observations on the biota of Sable Island, along with casual observations in the journals of successive superintendents are vague, and emphasize exploitability. John Gilpin’s 1854 and 1855 visits were the first by a knowledgeable naturalist. His published 1859 “lecture” includes sketchy descriptions of the flora, birds, pinnipeds, and a list of collected marine molluscs. Reflecting growth of ‘cabinet’ natural history in New England, J. W. Maynard in 1868 collected a migrant sparrow in coastal Massachusetts, soon named Ipswich Sparrow and recognized as nesting on Sable Island. This persuaded New York naturalist Jonathan Dwight to visit the island in June-July1894 and produce a substantial monograph on the sparrow. He in turn encouraged Superintendent Bouteiller’s family to send him many bird specimens, some very unusual, now in the American Museum of Natural History. Dominion Botanist John Macoun made the first extensive collection of the island’s plants in 1899, but only wrote a casual account of the biota. He possibly also promoted the futile tree-planting experiment in May 1901 directed by William Saunders, whose son, W. E., published some observations on the island’s birds, and further encouraged the Bouteillers to make and publish systematic bird observations, 1901- 1907.