History in Pakistan and the Will to Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Family Motacillidae" with Reference to Pakistan

Journal of Bioresource Management Volume 2 Issue 3 Article 10 Short Report: Description and Distribution of Wagtails "Family Motacillidae" with Reference to Pakistan Nadia Yousuf Bioresource Research Centre, Isalamabad, Pakistan Kainaat William Bioresource Research Centre, Islamabad, Pakistan Madeeha Manzoor Bioresource Research Centre, Islamabad, Pakistan, [email protected] Balqees Khanum Bioresource Research Centre, Islamabad, Pakistan Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/jbm Part of the Biodiversity Commons, and the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Yousuf, N., William, K., Manzoor, M., & Khanum, B. (2015). Short Report: Description and Distribution of Wagtails "Family Motacillidae" with Reference to Pakistan, Journal of Bioresource Management, 2 (3). DOI: 10.35691/JBM.5102.0034 ISSN: 2309-3854 online This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Bioresource Management by an authorized editor of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Short Report: Description and Distribution of Wagtails "Family Motacillidae" with Reference to Pakistan © Copyrights of all the papers published in Journal of Bioresource Management are with its publisher, Center for Bioresource Research (CBR) Islamabad, Pakistan. This permits anyone to copy, redistribute, remix, transmit and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes provided the original work and source is appropriately cited. Journal -

Health Facilities in Thatta- Sindh Province

PAKISTAN: Health facilities in Thatta- Sindh province Matiari Balochistan Type of health facilities "D District headquarter (DHQ) Janghari Tando "T "B Tehsil headquarter (THQ) Allah "H Civil hospital (CH) Hyderabad Yar "R Rural health center (RHC) "B Basic health unit (BHU) Jamshoro "D Civil dispensary (CD) Tando Las Bela Hafiz Road Shah "B Primary Boohar Muhammad Ramzan Secondary "B Khan Haijab Tertiary Malkhani "D "D Karachi Jhirck "R International Boundary MURTAZABAD Tando City "B Jhimpir "B Muhammad Province Boundary Thatta Pir Bux "D Brohi Khan District Boundary Khair Bux Muhammad Teshil Boundary Hylia Leghari"B Pinyal Jokhio Jungshahi "D "B "R Chatto Water Bodies Goth Mungar "B Jokhio Chand Khan Palijo "B "B River "B Noor Arbab Abdul Dhabeeji Muhammad Town Hai Palejo Thatta Gharo Thaheem "D Thatta D "R B B "B "H " "D Map Doc Name: PAK843_Thatta_hfs_L_A3_ "" Gujjo Thatta Shah Ashabi Achar v1_20190307 Town "B Jakhhro Creation Date: 07 March 2019 Badin Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS84 Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1:690,000 Haji Ghulammullah Pir Jo "B Muhammad "B Goth Sodho RAIS ABDUL 0 10 20 30 "B GHANI BAGHIAR Var "B "T Mirpur "R kms ± Bathoro Sindh Map data source(s): Mirpur GAUL, PCO, Logistic Cluster, OCHA. Buhara Sakro "B Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any Thatta opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Ghfbooksouthasia.Pdf

1000 BC 500 BC AD 500 AD 1000 AD 1500 AD 2000 TAXILA Pakistan SANCHI India AJANTA CAVES India PATAN DARBAR SQUARE Nepal SIGIRIYA Sri Lanka POLONNARUWA Sri Lanka NAKO TEMPLES India JAISALMER FORT India KONARAK SUN TEMPLE India HAMPI India THATTA Pakistan UCH MONUMENT COMPLEX Pakistan AGRA FORT India SOUTH ASIA INDIA AND THE OTHER COUNTRIES OF SOUTH ASIA — PAKISTAN, SRI LANKA, BANGLADESH, NEPAL, BHUTAN —HAVE WITNESSED SOME OF THE LONGEST CONTINUOUS CIVILIZATIONS ON THE PLANET. BY THE END OF THE FOURTH CENTURY BC, THE FIRST MAJOR CONSOLIDATED CIVILIZA- TION EMERGED IN INDIA LED BY THE MAURYAN EMPIRE WHICH NEARLY ENCOMPASSED THE ENTIRE SUBCONTINENT. LATER KINGDOMS OF CHERAS, CHOLAS AND PANDYAS SAW THE RISE OF THE FIRST URBAN CENTERS. THE GUPTA KINGDOM BEGAN THE RICH DEVELOPMENT OF BUILT HERITAGE AND THE FIRST MAJOR TEMPLES INCLUDING THE SACRED STUPA AT SANCHI AND EARLY TEMPLES AT LADH KHAN. UNTIL COLONIAL TIMES, ROYAL PATRONAGE OF THE HINDU CULTURE CONSTRUCTED HUNDREDS OF MAJOR MONUMENTS INCLUDING THE IMPRESSIVE ELLORA CAVES, THE KONARAK SUN TEMPLE, AND THE MAGNIFICENT CITY AND TEMPLES OF THE GHF-SUPPORTED HAMPI WORLD HERITAGE SITE. PAKISTAN SHARES IN THE RICH HISTORY OF THE REGION WITH A WEALTH OF CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT AROUND ISLAM, INCLUDING ADVANCED MOSQUE ARCHITECTURE. GHF’S CONSER- VATION OF ASIF KHAN TOMB OF THE JAHANGIR COMPLEX IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN WILL HELP PRESERVE A STUNNING EXAMPLE OF THE GLORIOUS MOGHUL CIVILIZATION WHICH WAS ONCE CENTERED THERE. IN THE MORE REMOTE AREAS OF THE REGION, BHUTAN, SRI LANKA AND NEPAL EACH DEVELOPED A UNIQUE MONUMENTAL FORM OF WORSHIP FOR HINDUISM. THE MOST CHALLENGING ASPECT OF CONSERVATION IS THE PLETHORA OF HERITAGE SITES AND THE LACK OF RESOURCES TO COVER THE COSTS OF CONSERVATION. -

Consolidated List of Hgos (Hajj-2017, 1438

Consolidated List of HGOs (Hajj-2017, 1438 A.H.) as on 21-Jul-2017 SR # ENR # MNZ # HAJJ LICENSE NAME OF COMPANY NAME OFFICE # CELL # IN PAK CELL # IN KSA ADDRESS QUOTA OFFICE NO 5-A,FIRST FLOOR MAKKAH TRADE CENTRE 1 1101/P 3572 1101-3572/P KARWAN AL AHMAD HAJJ SERVICES PVT LTD HAZRAT HUSSAIN 0915-837512 0316-5252528 00966-582299869 95 KARKHANO MARKET PESHAWAR. 2-A FIRST FLOOR MAKKAH TRADE CENTRE,KARKHANO 2 1102/P 3635 1102-3635/P MINHAJ TOURS PVT LTD SPIN GULAB 0915-837508 0346-4646670 00966-555071685 95 MARKET,PESHWAR. UG 93-95 DEANS TRADE CENTER OPP,STATE BANK 3 1103/P 3638 1103-3638/P PIR INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD NAZIA PARVEEN 0915-253025 0333-9040801 00966-559028582 95 PESHAWAR CANTT 4 1104/P 3835 1104-3835/P AL NISMA HAJJ & UMRAH PVT LTD AWAL MIR 0969-512234 0333-9988623 00966-537307571 SANAM GUL MARKEET MAIN LARI ADDA LAKKI MARWAT 80 5 1105/P 3837 1105-3837/P SHOAIB HAJJ AND UMRAH PVT LTD MUHAMMAD SOHAIL 0915-250294 0336-9397290 00966-598835209 UG-151 DEANS TRADE CENTER PESHAWAR CANTT. 95 QURESHI ENTERPRISES MEDICINE PLAZA KATCHERY ROAD 6 1106/P 3842 1106-3842/P JABAL E NOOR TRAVEL & TOURS PVT LTD KHAN AYAZ KHAN 0928-622865 0333-9749394 00966-535808035 95 BANNU 1 JUMA KHAN PLAZA FAKHR-E-ALAM ROAD PESHAWAR 7 1107/P 2615 1107-2615/P AMAN ULLAH HAJJ TRAVEL & TOURS PVT LTD AMAN ULLAH 0915-284096 0300-5900786 00966-543723174 102 CANTT. UG3, PAK BUSINESS CENTER, NEAR AMIN HOTEL, GT ROAD 8 1108/P 2598 1108-2598/P KARWAN E HAMZA PVT LTD MUHAMMAD KAMRAN ZEB 0912-565524 0336-5866085 00966-554299061 186 HASHTNAGRI, PESHAWAR FLAT NO 6B, FAISAL -

Second Lahore Biennale: Between the Sun and the Moon Curated by Hoor Al Qasimi Features 20+ New Commissions and Work by More Than 70 International Artists

For Immediate Release 6 January 2020 Second Lahore Biennale: between the sun and the moon Curated by Hoor Al Qasimi Features 20+ New Commissions and Work by More Than 70 International Artists Installed Across Cultural and Heritage Sites Throughout Lahore, Pakistan, from 26 January to 29 February 2020 Lahore, Pakistan—6 January 2020—The Lahore Biennale Foundation today revealed a list of over 70 participating artists for the second edition of the Lahore Biennale (LB02), running from 26 January through 29 February 2020. Curated by Hoor Al Qasimi, Director of the Sharjah Art Foundation in Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, LB02: between the sun and the moon brings a plethora of artistic projects to cultural and heritage sites throughout the city of Lahore including more than 20 new commissions by artists from across the region and around the world, including Alia Farid, Diana Al-Hadid, Hassan Hajjaj, Haroon Mirza, Hajra Waheed and Simone Fattal, among many others. Other participating artists include Anwar Saeed, Rasheed Araeen and the late Madiha Aijaz. With a focus on the Global South, where ongoing social disaffection is being aggravated by climate change, LB02 responds to the cultural and ecological history of Lahore and aims to awaken awareness of humanity’s daunting contemporary predicament. Works presented in LB02 will explore human entanglement with the environment while revisiting traditional understandings of the self and their cosmological underpinnings. Inspiration for this thematic focus is drawn from intellectual and cultural exchange between South and West Asia. “For centuries, inhabitants of these regions oriented themselves with reference to the sun, the moon, and the constellations. -

LAHORE-Ren98c.Pdf

Renewal List S/NO REN# / NAME FATHER'S NAME PRESENT ADDRESS DATE OF ACADEMIC REN DATE BIRTH QUALIFICATION 1 21233 MUHAMMAD M.YOUSAF H#56, ST#2, SIDIQUE COLONY RAVIROAD, 3/1/1960 MATRIC 10/07/2014 RAMZAN LAHORE, PUNJAB 2 26781 MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD H/NO. 30, ST.NO. 6 MADNI ROAD MUSTAFA 10-1-1983 MATRIC 11/07/2014 ASHFAQ HAMZA IQBAL ABAD LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 3 29583 MUHAMMAD SHEIKH KHALID AL-SHEIKH GENERAL STORE GUNJ BUKHSH 26-7-1974 MATRIC 12/07/2014 NADEEM SHEIKH AHMAD PARK NEAR FUJI GAREYA STOP , LAHORE, PUNJAB 4 25380 ZULFIQAR ALI MUHAMMAD H/NO. 5-B ST, NO. 2 MADINA STREET MOH, 10-2-1957 FA 13/07/2014 HUSSAIN MUSLIM GUNJ KACHOO PURA CHAH MIRAN , LAHORE, PUNJAB 5 21277 GHULAM SARWAR MUHAMMAD YASIN H/NO.27,GALI NO.4,SINGH PURA 18/10/1954 F.A 13/07/2014 BAGHBANPURA., LAHORE, PUNJAB 6 36054 AISHA ABDUL ABDUL QUYYAM H/NO. 37 ST NO. 31 KOT KHAWAJA SAEED 19-12- BA 13/7/2014 QUYYAM FAZAL PURA LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 1979 7 21327 MUNAWAR MUHAMMAD LATIF HOWAL SHAFI LADIES CLINICNISHTER TOWN 11/8/1952 MATRIC 13/07/2014 SULTANA DROGH WALA, LAHORE, PUNJAB 8 29370 MUHAMMAD AMIN MUHAMMAD BILAL TAION BHADIA ROAD, LAHORE, PUNJAB 25-3-1966 MATRIC 13/07/2014 SADIQ 9 29077 MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD ST. NO. 3 NAJAM PARK SHADI PURA BUND 9-8-1983 MATRIC 13/07/2014 ABBAS ATAREE TUFAIL QAREE ROAD LAHORE , LAHORE, PUNJAB 10 26461 MIRZA IJAZ BAIG MIRZA MEHMOOD PST COLONY Q 75-H MULTAN ROAD LHR , 22-2-1961 MA 13/07/2014 BAIG LAHORE, PUNJAB 11 32790 AMATUL JAMEEL ABDUL LATIF H/NO. -

State of Conservation Report by The

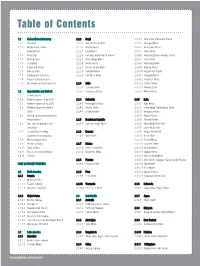

Report on State of Conservation of World Heritage Property Fort & Shalamar Gardens Lahore, Pakistan January, 2019 Government of the Punjab Directorate General of Archaeology Youth Affairs, Sports, Archaeology and Tourism Department Table of Contents Sr. Page Item of Description No. No. 1. Executive Summary 1 2. Introduction 3 3. Part-1. Report on decision WHC/18/42.COM/7B.14 5 4. Part-2. Report on State of Conservation of Lahore Fort 13 5. Report on State of Conservation of Shalamar Gardens 37 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Fort & Shalamar Gardens in Lahore, Pakistan were inscribed on the World Heritage List of monuments in 1981. The state of Conservation of the Fort and Shalamar Gardens were discussed in the 42nd Session of the World Heritage Committee (WHC) in July, 2018 at Manama, Bahrain. In that particular session the Committee took various decisions and requested the State Party to implement them and submit a State of Conservation Report to the World Heritage Centre for its review in the 43rd Session of the World Heritage Committee. The present State of Conservation Report consists of two parts. In the first part, progress on the decisions of the 42nd Session of the WHC has been elaborated and the second part of the report deals with the conservation efforts of the State Party for Lahore Fort and Shalamar Gardens. Regarding implementation of Joint World Heritage Centre/ICOMOS Reactive Monitoring Mission (RMM) recommendations, the State Party convened a series of meetings with all the stakeholders including Federal Department of Archaeology, UNESCO Office Islamabad, President ICOMOS Pakistan, various government departments of the Punjab i.e., Punjab Mass-Transit Authority, Lahore Development Authority, Metropolitan Corporation of Lahore, Zonal Revenue Authorities, Walled City of Lahore Authorities, Technical Committee on Shalamar Gardens and eminent national & international heritage experts and deliberated upon the recommendations of the RMM and way forward for their implementation. -

Trams Der Welt / Trams of the World 2021 Daten / Data © 2021 Peter Sohns Seite / Page 1

www.blickpunktstrab.net – Trams der Welt / Trams of the World 2021 Daten / Data © 2021 Peter Sohns Seite / Page 1 Algeria ... Alger (Algier) ... Metro ... 1435 mm Algeria ... Alger (Algier) ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Algeria ... Constantine ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Algeria ... Oran ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Algeria ... Ouragla ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Algeria ... Sétif ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Algeria ... Sidi Bel Abbès ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Buenos Aires, DF ... Metro ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Buenos Aires, DF - Caballito ... Heritage-Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Buenos Aires, DF - Lacroze (General Urquiza) ... Interurban (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Buenos Aires, DF - Premetro E ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Buenos Aires, DF - Tren de la Costa ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Córdoba, Córdoba ... Trolleybus Argentina ... Mar del Plata, BA ... Heritage-Tram (Electric) ... 900 mm Argentina ... Mendoza, Mendoza ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Mendoza, Mendoza ... Trolleybus Argentina ... Rosario, Santa Fé ... Heritage-Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Argentina ... Rosario, Santa Fé ... Trolleybus Argentina ... Valle Hermoso, Córdoba ... Tram-Museum (Electric) ... 600 mm Armenia ... Yerevan ... Metro ... 1524 mm Armenia ... Yerevan ... Trolleybus Australia ... Adelaide, SA - Glenelg ... Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Australia ... Ballarat, VIC ... Heritage-Tram (Electric) ... 1435 mm Australia ... Bendigo, VIC ... Heritage-Tram -

Fighting on Different Fronts | DAWN.COM

10/31/12 Fighting on different fronts | DAWN.COM Dawn.com Dawn Urdu DawnNews TV ePaper Herald CityFM89 Events Dawn Relief Wednesday 31st October 2012 | Zilhaj 14, 1433 HEADLINES Karachi law and order case: SC resumes hearing Search Dawn.com Pakistan Fighting on different fronts Asif Noorani | 2 days ago 0 Tw eet 16 Like 30 9 Yasmeen Lari Yasmeen Lari poses quite a challenge to any writer who attempts to profile her. She is dynamic, energetic and totally committed to her projects. As someone who has followed her career for two decades, I have been highly impressed with her dedication to many causes that she has espoused but wasn’t aware of her meticulous attention to details until, earlier this month, when I saw her at work at the World Heritage Site, the necropolis in Makli, where under her stewardship The Heritage Foundation (THF) of Pakistan is involved in salvaging some tombs. THF had earlier documented as many as 400 tombs and isolated graves. That afternoon I saw Lari spending the better part of an hour examining the work that is being done by specially trained staff members. She looked intently at almost all the bricks that are being fixed back in the dilapidated wall of a 500-year-old tomb. Her unflinching dedication to her work is a trait she seems to have inherited from her father. Lari, who was just a toddler when her father was the Deputy Commissioner of Lahore at the time of Partition, recalls that he had dual responsibilities – to shield the Hindus and Sikhs in Lahore and at the same time to provide food and shelter to the Muslim refugees who had under dangerous circumstances managed to cross the newly created border. -

Gendered 'Landscape': Jahanara Begum's Patronage, Piety and Self

DISSERTATION Titel der Dissertation ―Gendered ‗Landscapes‘: Jahan Ara Begum‘s (1614-1681) Patronage, Piety and Self-Representation in 17th C Mughal India‖ Band 1 von 1 Verfasser Afshan Bokhari angestrebter akademischer Grad Doktor der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) Wien, 2009 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 092315 Dissertationsgebiet lt. Studienblatt: Kunstgeschichte Betreuerin/Betreuer: Univ. Prof. Dr. Ebba Koch TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page 0 Table of Contents 1-2 Curriculum Vitae 3-5 Acknowledgements 6-7 Abstract 8 List of Illustration 9-12 Introduction 13-24 Figures 313-358 Bibliography 359-372 Chapter One: 25-113 The Presence and Paradigm of The „Absent‟ Timurid-Mughal Female 1.1 Recent and Past Historiographies: Ruby Lal, Ignaz Goldziher, Leslie Pierce, Stephen Blake 1.2 Biographical Sketches: Timurid and Mughal Female Precedents: Domesticity and Politics 1.2.1 Timurid Women (14th-15th century) 1.2.2 Mughal Women (16th – 17th century) 1.2.3 Nur Jahan (1577-1645): A Prescient Feminist or Nemesis? 1.2.4 Jahan Ara Begum (1614-1681): Establishing Precedents and Political Propriety 1.2.5 The Body Politic: The Political and Commercial Negotiations of Jahan Ara‘s Well-Being 1.2.6 Imbuing the Poetic Landscape: Jahan Ara‘s Recovery 1.3 Conclusion Chapter Two: 114-191 „Visions‟ of Timurid Legacy: Jahan Ara Begum‟s Piety and „Self- Representation‟ 2.1 Risala-i-Sahibiyāh: Legacy-Building ‗Political‘ Piety and Sufi Realization 2.2 Galvanizing State to Household: Pietistic Imperatives Dynastic Legitimacy 2.3 Sufism, Its Gendered Dimensions and Jahan -

Global Report Global Metro Projects 2020.Qxp

Table of Contents 1.1 Global Metrorail industry 2.2.2 Brazil 2.3.4.2 Changchun Urban Rail Transit 1.1.1 Overview 2.2.2.1 Belo Horizonte Metro 2.3.4.3 Chengdu Metro 1.1.2 Network and Station 2.2.2.2 Brasília Metro 2.3.4.4 Guangzhou Metro Development 2.2.2.3 Cariri Metro 2.3.4.5 Hefei Metro 1.1.3 Ridership 2.2.2.4 Fortaleza Rapid Transit Project 2.3.4.6 Hong Kong Mass Railway Transit 1.1.3 Rolling stock 2.2.2.5 Porto Alegre Metro 2.3.4.7 Jinan Metro 1.1.4 Signalling 2.2.2.6 Recife Metro 2.3.4.8 Nanchang Metro 1.1.5 Power and Tracks 2.2.2.7 Rio de Janeiro Metro 2.3.4.9 Nanjing Metro 1.1.6 Fare systems 2.2.2.8 Salvador Metro 2.3.4.10 Ningbo Rail Transit 1.1.7 Funding and financing 2.2.2.9 São Paulo Metro 2.3.4.11 Shanghai Metro 1.1.8 Project delivery models 2.3.4.12 Shenzhen Metro 1.1.9 Key trends and developments 2.2.3 Chile 2.3.4.13 Suzhou Metro 2.2.3.1 Santiago Metro 2.3.4.14 Ürümqi Metro 1.2 Opportunities and Outlook 2.2.3.2 Valparaiso Metro 2.3.4.15 Wuhan Metro 1.2.1 Growth drivers 1.2.2 Network expansion by 2025 2.2.4 Colombia 2.3.5 India 1.2.3 Network expansion by 2030 2.2.4.1 Barranquilla Metro 2.3.5.1 Agra Metro 1.2.4 Network expansion beyond 2.2.4.2 Bogotá Metro 2.3.5.2 Ahmedabad-Gandhinagar Metro 2030 2.2.4.3 Medellín Metro 2.3.5.3 Bengaluru Metro 1.2.5 Rolling stock procurement and 2.3.5.4 Bhopal Metro refurbishment 2.2.5 Dominican Republic 2.3.5.5 Chennai Metro 1.2.6 Fare system upgrades and 2.2.5.1 Santo Domingo Metro 2.3.5.6 Hyderabad Metro Rail innovation 2.3.5.7 Jaipur Metro Rail 1.2.7 Signalling technology 2.2.6 Ecuador -

Ajoka Theatre As an Icon of Liberal Humanist Values

Review of Education, Administration and Law (REAL) Vol. 4, (1) 2021, 279-286 Ajoka Theatre as an Icon of Liberal Humanist Values a b c d Ambreen Bibi, Saimaan Ashfaq, Qazi Muhammad Saeed Ullah, Naseem Abbas a PhD Scholar / Associate Lecturer, Department of English, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan Email: [email protected] b Associate Lecturer, Department of English, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan Email: [email protected] c Associate Lecturer, Department of English, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan. Email: [email protected] d Visiting Lecturer, Department of English, BZU, Multan, Pakistan Email: [email protected] ARTICLE DETAILS ABSTRACT History: There are multiple ways of transferring human values, cultures and Accepted 23 March 2021 history from one generation to another. Literature, Art, Paintings and Available Online March 2021 Theatrical performances are the real reflection of any civilization. In the history of subcontinent, theatres played a vital role in promoting the Keywords: Pakistani and Indian history; Mughal culture and traditions. Pakistani Ajoka Theatre, Liberal theatre, “Ajoka” played significant role to propagate positive, Humanism, Performance, humanitarian and liberal humanist values. This research aims to Culture, Dictatorship investigate the transformation in the history of Pakistani theatre specifically the “Ajoka” theatre that was established under the JEL Classification: government of military dictatorship in Pakistan in the late nineteenth L82 century. It was not a compromising time for the celebration of liberal humanist values in Pakistan as the country was under the rules of military dictatorship. The present study is intended to explore the DOI: 10.47067/real.v4i1.135 dissemination of liberal humanist values in the plays and performances of “Ajoka” theatre.