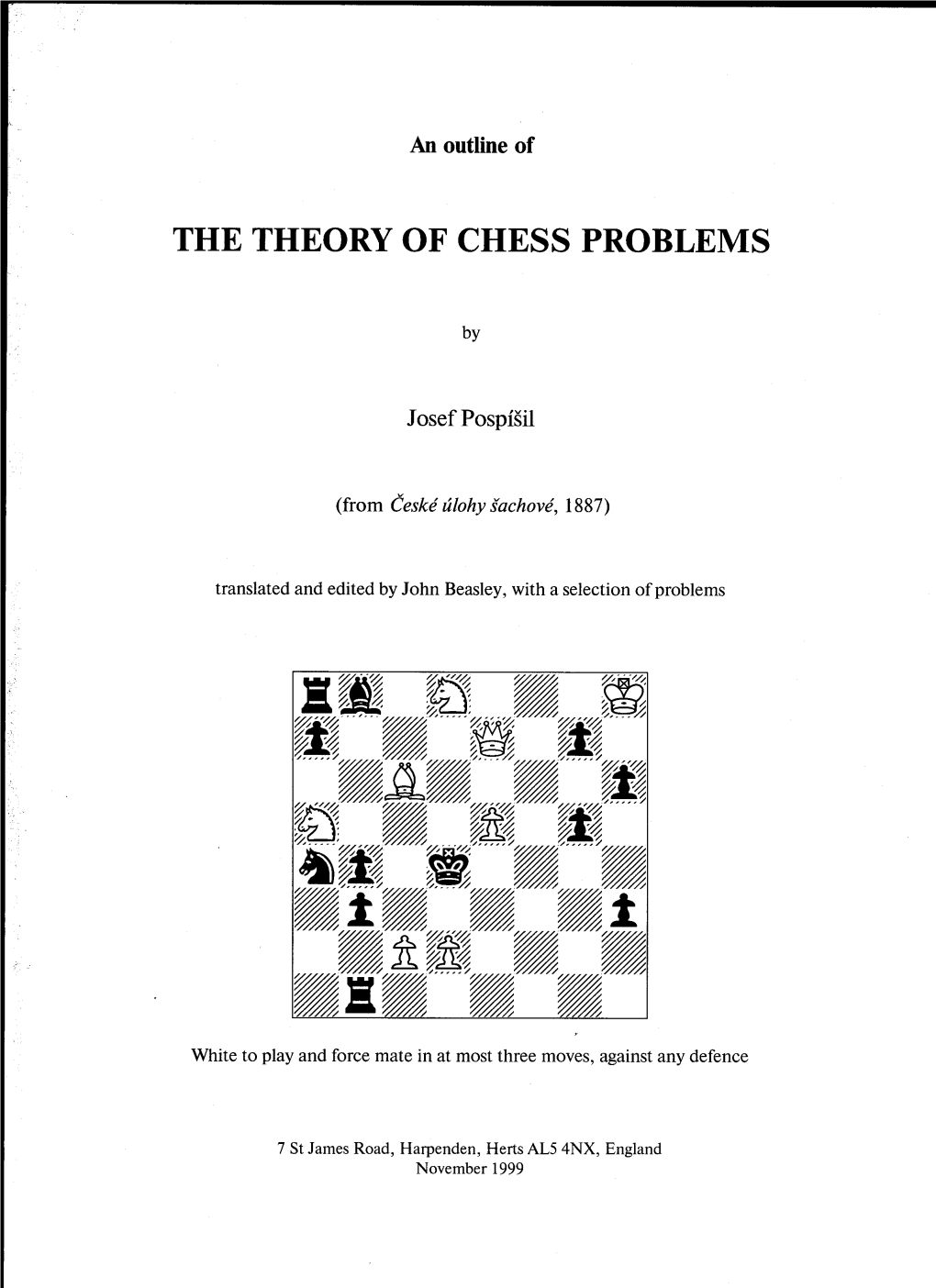

The Theory of Chess Problems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Play Chess

EVERYMAN CHESS Vladimir Vukovic One of the finest chess books ever written, the Art of Attack has been transcribed into algebraic notation for the first time. In this revised edition of the great classic, the author expounds both the basic principles and the most complex forms of attack on the king, A study of this masterpiece will ado power and bnlliance to any chess enthusiast s play EVERYMAN CHESS www.everymanchess.com published In the UK by Gloucester Publishers pic distributed in the US by the Globe Peouot Press Contents Symbols 4 Preface by John Nunn 5 Introduction 6 1 The attack against the uncastled king 14 2 The attack on the king that has lost the right to castle 28 3 On castling and attacking the castled position in general 51 4 Mating patterns 66 5 Focal-points 80 6 The classic bishop sacrifice 121 7 Ranks, files, and diagonals in the attack on the castled king 142 8 Pieces and pawns in the attack on the castled king 183 9 The attack on the fianchettoed and queenside castling positions 231 10 Defending against the attack on the castled king 247 1 1 The phases of the attack on the castled king 293 12 The attack on the king as an integral part of the game 334 Index of Players 350 Index of Openings 352 Symbols + check # checkmate x capture ! ! brilliant move ! good move !? interesting move ?! dubious move ? bad move ?? blunder Ch championship Ct candidates event OL olympiad 1-0 the game ends in a win for White V2 -V2 the game ends in a draw 0- 1 the game ends in a win for Black (n) nth match game ( D) see next diagram Preface by John Nunn Attacking the enemy king is one of the most exciting parts of chess, but it is also one of the hardest to play accurately. -

The 5Th Belgrade Chess Problems Festival Report by Milan Velimirović the Fifth Successive Festival Took Place from 2Nd to 4Th of May 2008

Mat Plus Review Summer 2008 The 5th Belgrade Chess Problems Festival Report by Milan Velimirović The fifth successive Festival took place from 2nd to 4th of May 2008. As usual a good number of guests from abroad were welcomed: Dinu-Ioan Nicula (ROM), Aleksander Leontyev (RUS), Andrey Selivanov (RUS), Eric Huber (ROM), Fadil Abdurahmanović (BIH), Iļja Ketris (LAT), Ivan Denkovski (MAK), Kostas Prentos (GRE), Michal Dragoun (CZE), Piotr Murdzia (POL), Valery Kopyl with his lovely daughter Valeria (UKR) and Živko Janevski (MAK). You may have noticed the exception from the alphabetical order of that list, but there is a good reason for it: Dinu-Ioan Nicula is the only foreign composer who has attended all five Festivals, and if he comes again next year the organizers could consider the idea of promoting him into an honorary participant. Anyway, all guests have been treated by the home team in a traditionally warm and friendly way. For the record, the participants from Serbia were: Bogoljub Trifunović, Borislav Gađanski, Borislav Ilinčić, Božidar Brujić, Božidar Šoškić, Branislav Đurašević, Darko Šaljić, Dragoljub Đokić, Goran Janković, Goran M. Todorović, Goran Škare, Igor Spirić, Joza Tucakov, Marjan Kovačević, Mihajlo Milanović, Milan Velimirović, Miodrag Radomirović, Mirko Miljanić, Nikola Miljaković, Nikola Petković, Petar Opening speech: Milan Milićević, president Šoškić, Radomir Mićunović, Slobodan of Chess club “Beograd Beopublikum”, Šaletić, Stevan B. Bokan, Tomislav Petrović, accompanied by Marjan Kovačević Vladimir Podinić and Zoran Sibinović. The programme was very busy and here is a brief report of all the events. Friday, May 2nd, 16:00. All participants were allowed to take part in a Machine Gun Solving event. -

Synthetic Games

S\TII}IETIC GAh.fES Synthetic Garnes Play a shortest possible game leading tCI ... G. P. Jelliss September 1998 page I S1NTHETIC GAI\{ES CONTENTS Auto-Surrender Chess BCM: British Chess Magazine, Oppo-Cance llati on Che s s CA'. ()hess Amafeur, EP: En Part 1: Introduction . .. .7 5.3 Miscellaneous. .22 Passant, PFCS'; Problemist Fairy 1.1 History.".2 Auto-Coexi s tence Ches s Chess Supplement, UT: Ultimate 1.2 Theon'...3 D3tnamo Chess Thernes, CDL' C. D" I,ocock, GPJ: Gravitational Chess G. P. Jelliss, JA: J. Akenhead. Part 2: 0rthodox Chess . ...5 Madrssi Chess TGP: T. G. Pollard, TRD: 2. I Checknrates.. .5 Series Auto-Tag Chess T. R. Dar,vson. 2.2 Stalernates... S 2.3 Problem Finales. I PART 1 I.I HISTOR,Y 2.4 Multiple Pawns... l0 INTRODUCTIOT{ Much of my information on the 2.,5 Kings and Pawns".. l1 A'synthetic game' is a sequence early history comes from articles 2.6 Other Pattern Play...13 of moves in chess, or in any form by T. R. Dar,vson cited below, of variant chess, or indesd in any Chess Amsteur l9l4 especially. Part 3. Variant Play . ...14 other garne: which simulates the 3.1 Exact Play... 14 moves of a possible, though Fool's Mste 3 .2 Imitative Direct. l 5 usually improbable, actual game? A primitive example of a 3.3 Imitative Oblique.. " l6 and is constructed to show certain synthetic game in orthodox chess 3.4 Maximumming...lT specified events rvith fewest moves. is the 'fool's mate': l.f3l4 e6l5 3.5 Seriesplay ...17 The following notes on history 2.g4 Qh4 mate. -

Capablanca and Res Hevsky

.. IIITI ••• iiiiii1iii ,\ lIubscrip(\on 10 CH I';"" Rl~\'II , ;\V makN' "" Idenl ""lc~ ftu' your own .(:n(:",,,1 "nd 10 mnkc ).:'Ift ~"Io"crl[>· Chrl~lm"8 JOi(1 fol' rlllal;" "5 ,"\d fde"d~ who n"l) now 110"" 10 ~·o'''' f";cnd~ . InIN'~~LCd in c h e~_ u,' who will Ih ,, ~ be g in'" Ill" 0]>- Why nOt JOl down now. 0" the C II ,.j~ 1 "',,~ (li(t 0",10 " 1>O,'I\I"ily 10 Ll·;,\B;-..' Chl)M b)' {ollowi"[t Ihe ['iell"'C [.'0 ... " ()n<:iO$Cd wllh Ihl~ I"~" (). Ihe n""' ~~ and *Id,'""""" (J",dc for i)(,JO''''''' ' '~ "OW ...",,,ill l:' In (,; Hl~SS H I ';\'I I'~\\" _ of )<0"" r,·i"" ... ~ " .. d h: ~ ,,~ "" .. d ,h,·,,, C I-I~;SS l{1,;VI I,,;\\' Thl ~ i~ wIlIClhllll<" )'U" k "ow YOur r"lcnd~ Will np- a ll y our CI",;sl"'''s .,r(:~(' '' I. Wc will I"ke ~""C or II 1"",.'.;I,,ll). EVI)!"}' moUlh Ih'T will 1.>0 r l)n.indll<[ of YOU. 'he d<ll"il~. We will ~ , ,,,., e'l("h ""h,",,"iJ>llon ",i,h I wilt Ih nnk you (or IlH rodnc;n" III"", 10 I h l) 1:"~'Hc"l (;"ri"l~h ri~o""" or theX ."Picture ..I)(O r o rQ uid.·en E !;SII) CIU':Vh "~ ,, II H';\\".crlCl!_ e n;"n(l":"":,;,,, ::,:,:,:,: ~'i,:; ill t ho world ",,01 Iori"o:lnl:' t hem a whOI() yo"r 0:'''''(' CHIU8T.\lAS CAHO to c",,11 you,' rrlcll" •. " of I'l e "~ '''' e lind cnjoym e nt. -

The Puzzling Side of Chess

TTHHEE PPUUZZZZLLIINNGG SSIIDDEE OOFF CCHHEESSSS Jeff Coakley SMORGASBORD V: December Sweets number 76 December 12, 2014 This week our dessert menu features a selection of six puzzles with a variety of flavours. Try one, or try them all. We hope you find something to your taste. Triple Loyd 40 w________w áwdwdwdwd] àdwdwdwdw] ßwdwdRdwd] ÞdwdwdKdw] Ýwdwdwdwd] ÜdwdwHwGw] Ûwdwdwdwd] ÚdwdwdwdQ] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw Place the black king on the board so that: A. Black is in checkmate. B. Black is in stalemate. C. White has a mate in 1. The types of problems presented in this column have appeared before on The Puzzling Side of Chess. If you are unfamiliar with them, examples with more detailed explanations are available in the archives. The holiday season means lots of travelling from point A to point B. And sometimes a late trip home. Take care. Take a cab. Passing Bishops 02 w________wposition A áwgwgwgwg] àdwdwdwdw] ßwdwdwdwd] Þdwdwdwdw] Ýwdwdwdwd] Üdwdwdwdw] Ûwdwdwdwd] ÚGwGwGwGw] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw w________wposition B áwGwGwGwG] àdwdwdwdw] ßwdwdwdwd] Þdwdwdwdw] Ýwdwdwdwd] Üdwdwdwdw] Ûwdwdwdwd] Úgwgwgwgw] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw Get from A to B in 15 moves. (eight white, seven black) The two sides alternate moves in the usual way. Position B should be reached after White’s eighth turn. The next problem, a miniature helpmate by Italian FM Andrea Malfagia, is from the 2014 Chess Cafe Puzzlers Cup. (See column 75.) It didn’t win a prize, but it was my personal favourite. Helpmate 12 w________w áwdNdwdwd] àdwiwdPdw] ßwdwdwdwd] ÞdwdwdKdw] ÝwdPdw)wd] Üdwdwdwdw] Ûwdwdwdwd] Údwdwdwdw] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw Helpmate in 2 Black moves first and helps White checkmate the black king on White’s second move. -

VARIANT CHESS 8 Page 97

July-December 1992 VARIANT CHESS 8 page 97 @ Copyright. 1992. rssN 0958-8248 Publisher and Editor G. P. Jelliss 99 Bohemia Road Variant Chess St Leonards on Sea TN37 6RJ (rJ.K.) In this issue: Hexagonal Chess, Modern Courier Chess, Escalation, Games Consultant Solutions, Semi-Pieces, Variants Duy, Indexes, New Editor/Publisher. Malcolm Horne Volume 1 complete (issues 1-8, II2 pages, A4 size, unbound): f10. 10B Windsor Square Exmouth EX8 1JU New Varieties of Hexagonal Chess find that we need 8 pawns on the second rank plus by G. P. Jelliss 5 on the third rank. I prefer to add 2 more so that there are 5 pawns on each colour, and the rooks are Various schemes have been proposed for playing more securely blocked in. There is then one pawn in chess on boards on which the cells are hexagons each file except the edge files. A nm being a line of instead of squares. A brief account can be found in cells perpendicular to the base-line. The Oxford Companion to Chess 1984 where games Now how should the pawns move? If they are to by Siegmund Wellisch I9L2, H.D.Baskerville L929, continue to block the files we must allow them only Wladyslaw Glinski L949 and Anthony Patton L975 to move directly forward. This is a fers move. For are mentioned. To these should be added the variety their capture moves we have choices: the other two by H. E. de Vasa described in Joseph Boyer's forward fers moves, or the two forward wazit NouveoLx, Jeux d'Ecltecs Non Orthodoxes 1954 moves, or both. -

13 Supplement Awards.Fm

No. 173 – Vol. XIV – July 2008 Supplement Awards Kozatska Shakhivnitsa 2005 . 194 Moscow Town 2006 . 195 C.M. Bent MT (2007) . 199 Iuri Akobia 70 JT 2007 . 203 Olimpiya Dunyasi 2006. 215 Hero Towns Match no. 5 (2005) . 220 Československy šach 2005-2006. 222 König & Turm 2005 . 230 Meleghegyi MT (2005) . 231 Šachova Skladba 2005-2006 . 235 Kozatska Shakhivnitsa 2005 Provisional/definitive published: Kozatska Shakhivnitsa 4-5(26-27) 2006. Judge: Vitaly Shevchenko (Zaporozhe, Ukraine). Type: informal international. Theme: none. Confirmation: no mention. Report: 4 studies by 4 composers, from Italy and Ukraine. No 16460 P. Rossi & M. Campioli No 16461 Franco Bertoli (Italy). 1.Sg3+ Kh2 XIIIIIIIIYprize 2.Se2+ Kh1 3.Sg3+ Kg1 4.Ke2 a2 5.Be5 Kh2 9k+-sN-+-+0 6.Se4+ Kh3 7.Sf2+ Kh4 8.Bf6+ Kg3 9.Be5+ Kh4 10.Bf6+ Kxh5 11.Sh3 Kg4 12.Sg1 b3 9+-zP-+-+-0 13.Kxd2 a3 14.Kc1 draws. 9-+P+-+-+0 HH: 5…b3 cooks, e.g. 6.h6 a1Q 7.Bxa1 Kh2 9+-+-+-+L0 8.Bd4 b2 9.h7 d1Q+ 10.Kxd1 b1Q+. 9-+-mK-+-+0 No 16462 F. Kapustin 9+-+-+-+-0 commendation 9-+-+pzp-+0 XIIIIIIIIYdedicated to V. Shevchenko 9sn-+-+-+l0 9-+-+-+-+0 d4a8 0044.22 5/5 Win BTM 9+-+p+-+p0 No 16460 Pietro Rossi & Marco Campioli 9-+-+-+-+0 (Italy). 1...Sb3+ 2.Kd3 Be4+ 3.Kxe2 Bf5 9+-+-+-+-0 4.Be8 Sd4+ 5.Kxf2 Sxc6 6.Sxc6 Kb7 7.Sd4 9-+-+-+-+0 Bd3 8.Bb5/i Bg6 9.Se6 wins. 9zP-+-+-+-0 i) “The triumph of domination!” 9P+K+-+-+0 No 16461 F. -

ORIGINAL PROBLEMS, Edited by Zoran Gavrilovski #2 / JUDGE: DRAGAN STOJNIĆ (SERBIA) 1879 Karol Mlynka Bratislava (Slovakia) 1880

ORIGINAL PROBLEMS, edited by Zoran Gavrilovski 1879 K. Mlynka 188 2 M. Basisty & 1885 K. Mlynka D D A. Vasilenko #2 / JUDGE : DRAGAN STOJNI Ć (S ERBIA ) 1.c8 ? (2. d8#) 1. Tc1? A (zz) kd4! x 1... t:f7+ 2. T:f7# 1.f7? (zugzwang) d4! 1...kd2 2.Td:c7 C kd3 3.Td1# 1879 Karol Mlynka 1880 Gerhard Maleika 2. H.M. 1881 Sergey Tkachenko 1... tg8 2.f:g8 S# 1...d:e4 2. D:e5# A 1.d6? B (2.d:c7#) c6! Bratislava (Slovakia) Gütersloh (Germany) Slavutich (Ukraine) 1... t:h7! 1... l~ 2.f8 D(T)# 1. TTTh6! (zugzwang) 1... k:e4 2. Lg6# 1...kd2 2.d:c7+ ke1 3. Tc1# A 1... t:f7+ 2.g:f7# 1. Dd2? (zugzwang) le2! 1... kd4 2.Td:c7 C kd3 3.Td5# 1... tg8 2.g7# 1...d:e4, d4 2. Df4# 1. TTTd:c7! (zugzwang) l 1... th7 2.g:h7# 1.. ~ 2.g4# 1... kd2 2. Tc1 kd3 3. Td1# k L 1... t:g6 2.f8 D(T)# 1... :e4 2. g6# k k T 1...e:f6 2. Sd6# 1... d4 2.d6 d3 3. d5# t -cross, change of 1. SSSf3! (2. D:e5# A) Salazar theme doubled, change P mates, promotions, - 1... k:e4 2. Dc2# of functions, and changed plus battery mates. (Author) 1...e:f6/d4 2. Sd6#/ T:e5# transferred continuations in three 1880 G. Maleika Changed mates. (Z.G.) phases of a miniature. (Author) 1.e6! (zugzwang) v v v 1883 Z. Gavrilovski 1886 I. -

No. 83 (Vol.VI) MAY 1986 PURE KNOWLEDGE Donald

No. 83 (Vol.VI) MAY 1986 PURE KNOWLEDGE Donald Michie Donald Michie is Director of Research at The Turing Institute, Glasgow. Thought, as every schoolboy knows, tually packaging, distributing and comes in two varieties, pure and im- marketing every kind of useful pure. Parents, clergy, teachers and knowledge. In these respects the others strive to instruct him in the challenge facing the knowledge engi- first, while all the time suspecting neer resembles that which confronted the presence of the second. So too those chemists of the last century with the special kind of knowledge who aspired to analyse the nature of to which EG readers are dedicated: biological compounds with a view to only truths which are pure, whole- developing, extracting, refining, syn- some and complete win a place. thesising, measuring and eventually In the practical Grandmaster's very (after a century or so as it turned different world approximate evalu- out) packaging, distributing and tions are found at every turn, lines marketing every kind of useful orga- may be recommended as "probably" nic compound. Today we take the sound, adjudications based on com- pharmaceutical industry for granted, mon sense rather than proof can be just as tomorrow, I believe, we will accepted, and questions of optimali- 1 take the automated knowledge in- ty or uniqueness of variations are dustry for granted. seen as academic distractions. How In this issue EG's editor John Roy- different from the EG world where croft comments or? some early fin- we find only elegance and certainty. dings in a marathon experiment on Whatever falls short, however infini- which he and Dr Alen Shapiro and tesimally, has no place at all. -

Chess Problems Made Easy

CHESS PROBLEMS MADE EASY HOW TO SOLVE – HOW TO COMPOSE by T. TAVERNER Chess Editor, “Daily News” With 250 illustrations by the author & famous composers An Electronic Edition Anders Thulin, Malmö · 2005-04-30 INTRODUCTION Chess Problem composing and solving have a charm peculiarly their own. Whether they add to or take from a player’s capacity for the game is a matter of opinion as to which all that need be said is that it depends upon the nature of the interest awakened, the opportunities available, and, ultimately, the relative amount of time devoted to each side of the game. The advantage of the Problem Art is that it may be entered into with- out the limitations attaching to the personal presence of an opponent, that it broadcasts what has well been called “the poetry of Chess” for the benefit of thousands who would otherwise be beyond the reach of its intellectual uplift, and that it throws open the door of entertainment and interest at times when actual play with an opponent over the board may be out of the question. Assuming that the reader is a lover of Chess and that his inclination turns towards problems, of which he seeks to acquire a working knowl- edge, our aim is the elementary one of setting him in the way of con- structing and solving them. The two processes are allied. In learning how a problem is created the student is bound to perceive how he may best approach the solution of others; in disentangling the complexities produced by good composers he acquires a constructive knowledge and ability of his own. -

The Games and Puzzles Journal, #8+9

rssN 0267 -36 9X o+o Incorporatind C HE SSIC S 4r9 G A N{ E S Issues8&gcombined t7 ry Nov 1988 - Feb 1989 {_} g O Copyright reserved P .f-/ Z-/ L E G-f.JELLISS, gg Bohemia Road St Leonards on Sea, TN37 6RJ J o U R_ F{ A T- Subscription t6 per year. GAME T.R.DAWSON INVENTION CENTENARY COMPETITION NIGHTRIDER 1989 - p. 119 TOURNEY - p. L?4 1987-88 POLY- AWARD OMINOES FOR CHESS pp. I22-L25 COMPOSITIONS p. 130 Contents II7 Circular Board Tangram, Hexominoes 13? WHATIS IN A GAME 118 Zines & Mags T26 CHESS VARIANTS 138 NUMEROLOGY & Various Board Games ProgressiV€r Mutation DIGITOLOGY Questions I2O CARD PLAY L28 NEWS & REVIEWS L4L LIBRARY RESEARCH Soccer as a Card Game I29 CHESS SOLUTIONS I42 GEOMETRY NOTES 2(5)SJe , Car(d) Park 130 AWARD 1987-88 143 TOURS & PATHS I22 DISSECTIONS T32 CHESS PROBLEMS I44 WORDS & LETTERS Pentominoes, Geometric 134 REVIEWS -SurveY of I47 Cryptic Crossword Jigsawsr Super-Domino Chess Problem Periodicals 148 MATHEMATICAL ART page 118 THE GAMES AND PUZZLES JOURNAL issue 8+9 ZINES & MAGS Tlte Games and Puzzles Journal. Apologies for the late appearance of this issue. Itve attowuetoworkonmyotherproJects,suchastheChessays. Actual publication date for this issue is 23 April 1989. I hope to catch up by issue L2 at least. Games Monthly. My prediction that this magazine looked like a stayer could not have been ilffii6fr$ITToloed after only four issues. Nominally it is being incorporated into Games International, but this appears to be only a commercial deal, allowing the latter to take over the formerrs subscription list and distribution network, not a combining of editorial input. -

EDITED B Y KASHDAN APRIL, T

, • WHITE MATES IN THREE MOVES By FRANK M. TEED EDITED B Y I . KASHDAN IN THIS ISSUE, KI NG WANDERINGS _ _ _ - _ - - - _ _ _ _ _ IRVING- CHERNEV WHY WE PLAY CHESS _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ BARNIE F. WINKELMAN PROBLEM REVIEW -- -- - - - - - - _ _ _ - OTTO WURZBURG APRIL,, t 933 - - - MONTHLY 25 cts. - - - ANNUALLY $2. .50 • 'Jhe REVIEW • I. KASHDAN. Editor in Chief I. A. HOROWITZ. OTTO WURZBURG, Problem Editor • } A ssociutc Editors FRED REINFELD, BERTRAM KADISH, Art D irector FRITZ BRIEGER. 8usineu Manager - - ..---' = . - .'-=-· - --c - 0----'- - -- - =. ==-== ~-- .-, -===-~--==c=~""==oo=~==="_~ .. ~. VOL. I No.4 Published M onthly APRIL. 1933 - --_- _ --0-- --=0--"=-- --. ----"'~'-". --~---,-- =- '-=== ---_.- N EWS OF THE M ONTH · - - - 2 KING WANDERINGS • - • • - 4 L IVING C H ESS . - - - - - - 6 GAME STUDY - - - - - - - - - - • 7 CURIOUS CHESS FACTS • • - - • 9 H ELPFUL HINTS - - - · - - -- -- • 10 W HY W E P LAY CHESS - . I I GAME D E PARTMENT - - - . - . 13 ANALYTICAL COMMENT - . - - - 22 M ISTAKES OF THE MASTERS - - - - - 24 E ND- GAME ANALYSIS - - • • 26 BooK REVIEW • • - - - - 27 P ROBLEM REVIEW - - - • • - - • 30 ~-- --_.- Publ!shed monthly by C h es.~ Review Yearly subscription in the United Sta te s $2 .50 60- 10 Roosevelt Avenue, W oodside , N . Y. Elsewhere $3.00 - - - - Single Copy 25 cents Telephone HAvemeyer 9-3828 Copyri ght 1933 b y Chess Review CONTRIBUTING EDITORS, IRVING CHERNEV --- - - - - - - - -- ARTHUR W . DAKE REUBEN PINE - - -- - - - - -- - - DONALD M ACMURRAY 8ARN IE F. W IN KELMAN _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ LESTER W . BRAND \ 2 THE CHESS REVIEW APRIL. 1933 • This is a stirring and worthy cause.