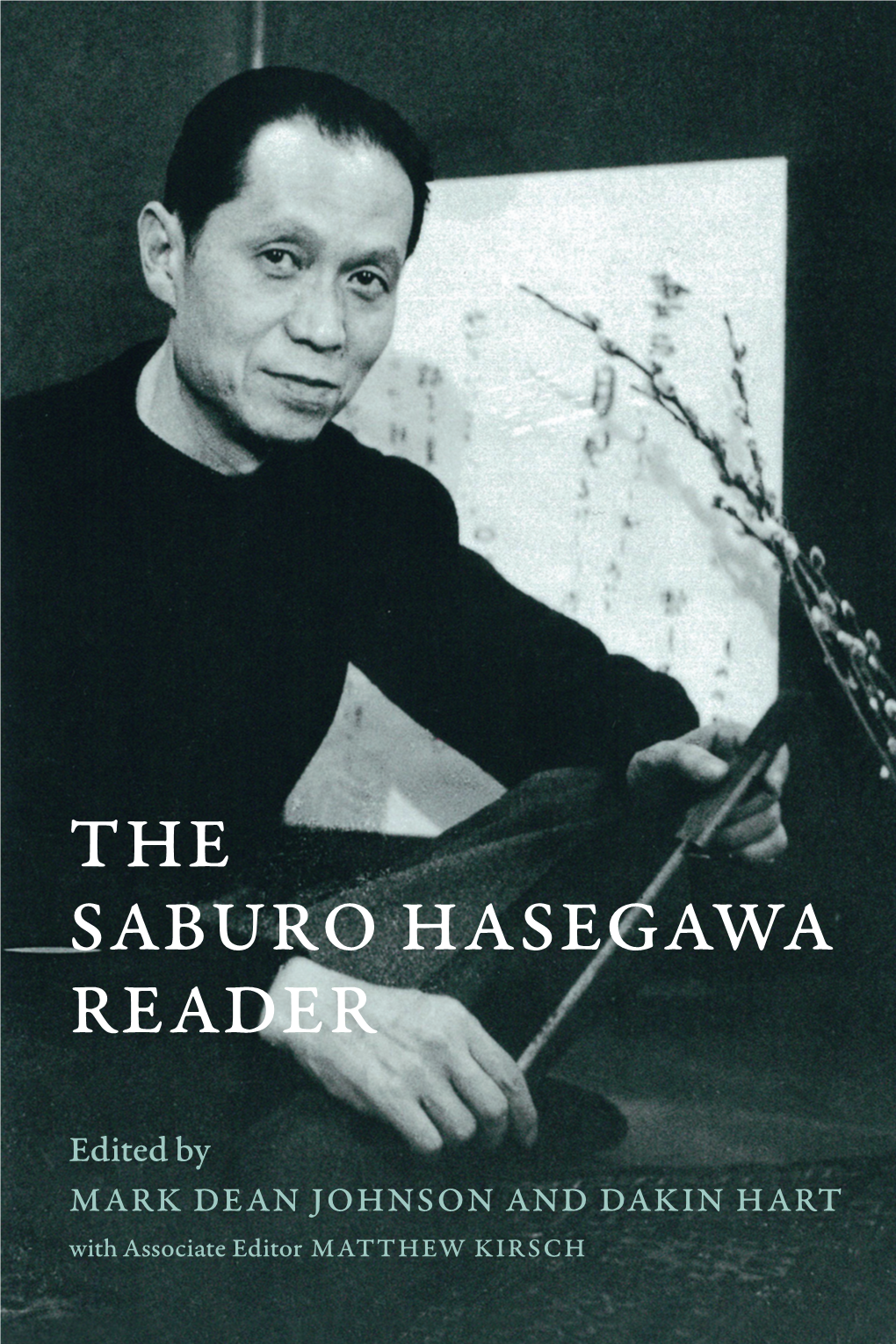

THE SABURO HASEGAWA READER Luminos Is the Open Access Monograph Publishing Program from UC Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of the Victorian and Edwardian Conceptions Of

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses The Graduate School Spring 2012 Hidden kisses, walled gardens, and angel-kinder: A Study of the Victorian and Edwardian conceptions of motherhood and childhood in Little Women , The Secret Garden , and Peter Pan Leah Marie Kirkpatrick James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019 Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Kirkpatrick, Leah Marie, "Hidden kisses, walled gardens, and angel-kinder: A Study of the Victorian and Edwardian conceptions of motherhood and childhood in Little omeW n, The eS cret Garden, and Peter Pan" (2012). Masters Theses. 253. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/master201019/253 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hidden Kisses, Walled Gardens, and Angel-kinder: a Study of the Victorian and Edwardian Conceptions of Motherhood and Childhood in Little Women, The Secret Garden, and Peter Pan Leah M. Kirkpatrick A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts English May 2012 Table of Contents List of Figures………………………………………………………………..…….....iii Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….....iv Introduction…………………………………………………………………………....1 I: The Invention of Childhood and the History of Children’s Literature…………..….3 II: An Angel in the House: the Victorian and Edwardian Wife and Mother………...27 III: Metaphysical Mothers: Mothers in The Secret Garden and Little Women………56 IV. -

The American Abstract Artists and Their Appropriation of Prehistoric Rock Pictures in 1937

“First Surrealists Were Cavemen”: The American Abstract Artists and Their Appropriation of Prehistoric Rock Pictures in 1937 Elke Seibert How electrifying it must be to discover a world of new, hitherto unseen pictures! Schol- ars and artists have described their awe at encountering the extraordinary paintings of Altamira and Lascaux in rich prose, instilling in us the desire to hunt for other such discoveries.1 But how does art affect art and how does one work of art influence another? In the following, I will argue for a causal relationship between the 1937 exhibition Prehis- toric Rock Pictures in Europe and Africa shown at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the new artistic directions evident in the work of certain New York artists immediately thereafter.2 The title for one review of this exhibition, “First Surrealists Were Cavemen,” expressed the unsettling, alien, mysterious, and provocative quality of these prehistoric paintings waiting to be discovered by American audiences (fig. ).1 3 The title moreover illustrates the extent to which American art criticism continued to misunderstand sur- realist artists and used the term surrealism in a pejorative manner. This essay traces how the group known as the American Abstract Artists (AAA) appropriated prehistoric paintings in the late 1930s. The term employed in the discourse on archaic artists and artistic concepts prior to 1937 was primitivism, a term due not least to John Graham’s System and Dialectics of Art as well as his influential essay “Primitive Art and Picasso,” both published in 1937.4 Within this discourse the art of the Ice Age was conspicuous not only on account of the previously unimagined timespan it traversed but also because of the magical discovery of incipient human creativity. -

Tenth-Century Painting Before Song Taizong's Reign

Tenth-Century Painting before Song Taizong’s Reign: A Macrohistorical View Jonathan Hay 1 285 TENT H CENT URY CHINA AND BEYOND 2 longue durée artistic 3 Formats 286 TENT H-CENT URY PAINT ING BEFORE SONG TAIZONG’S R EIGN Tangchao minghua lu 4 5 It 6 287 TENT H CENT URY CHINA AND BEYOND 7 The Handscroll Lady Guoguo on a Spring Outing Ladies Preparing Newly Woven Silk Pasturing Horses Palace Ban- quet Lofty Scholars Female Transcendents in the Lang Gar- 288 TENT H-CENT URY PAINT ING BEFORE SONG TAIZONG’S R EIGN den Nymph of the Luo River8 9 10 Oxen 11 Examining Books 12 13 Along the River at First Snow 14 15 Waiting for the Ferry 16 The Hanging Scroll 17 18 19 289 TENT H CENT URY CHINA AND BEYOND Sparrows and Flowers of the Four Seasons Spring MountainsAutumn Mountains 20 The Feng and Shan 21 tuzhou 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 290 TENT H-CENT URY PAINT ING BEFORE SONG TAIZONG’S R EIGN 29 30 31 32 Blue Magpie and Thorny Shrubs Xiaoyi Stealing the Lanting Scroll 33 291 TENT H CENT URY CHINA AND BEYOND 34 35 36 Screens 37 38 The Lofty Scholar Liang Boluan 39 Autumn Mountains at Dusk 292 TENT H-CENT URY PAINT ING BEFORE SONG TAIZONG’S R EIGN 40Layered Mountains and Dense Forests41 Reading the Stele by Pitted Rocks 42 It has Court Ladies Pinning Flowers in Their Hair 43 44 The Emperor Minghuang’s Journey to Shu River Boats and a Riverside Mansion 45 46 47tuzhang 48 Villagers Celebrating the Dragonboat Festival 49 Travelers in Snow-Covered Mountains and 50 . -

Title Call # Category

Title Call # Category 2LDK 42429 Thriller 30 seconds of sisterhood 42159 Documentary A 42455 Documentary A2 42620 Documentary Ai to kibo no machi = Town of love & hope 41124 Documentary Akage = Red lion 42424 Action Akahige = Red beard 34501 Drama Akai hashi no shita no nerui mizu = Warm water under bridge 36299 Comedy Akai tenshi = Red angel 45323 Drama Akarui mirai = Bright future 39767 Drama Akibiyori = Late autumn 47240 Akira 31919 Action Ako-Jo danzetsu = Swords of vengeance 42426 Adventure Akumu tantei = Nightmare detective 48023 Alive 46580 Action All about Lily Chou-Chou 39770 Always zoku san-chôme no yûhi 47161 Drama Anazahevun = Another heaven 37895 Crime Ankokugai no bijo = Underworld beauty 37011 Crime Antonio Gaudí 48050 Aragami = Raging god of battle 46563 Fantasy Arakimentari 42885 Documentary Astro boy (6 separate discs) 46711 Fantasy Atarashii kamisama 41105 Comedy Avatar, the last airbender = Jiang shi shen tong 45457 Adventure Bakuretsu toshi = Burst city 42646 Sci-fi Bakushū = Early summer 38189 Drama Bakuto gaijin butai = Sympathy for the underdog 39728 Crime Banshun = Late spring 43631 Drama Barefoot Gen = Hadashi no Gen 31326, 42410 Drama Batoru rowaiaru = Battle royale 39654, 43107 Action Battle of Okinawa 47785 War Bijitâ Q = Visitor Q 35443 Comedy Biruma no tategoto = Burmese harp 44665 War Blind beast 45334 Blind swordsman 44914 Documentary Blind woman's curse = Kaidan nobori ryu 46186 Blood : Last vampire 33560 Blood, Last vampire 33560 Animation Blue seed = Aokushimitama blue seed 41681-41684 Fantasy Blue submarine -

Changes to the Basic Resident Registration Law ~Foreign

Update 258 Changes to the Basic Resident Registration Law ~Foreign residents will be subject to the Basic Resident Registration Law~ Quotation from Portal Site on Policies for Foreign Residents by Cabinet Office, Government of Japan http://www8.cao.go.jp/teiju-portal/eng/policy/index.html (English) http://www8.cao.go.jp/teiju-portal/port/index.html (Português) http://www8.cao.go.jp/teiju-portal/espa/index.html (Español) Foreign residents will be listed on the Basic Resident Registration With the soaring number of foreign nationals entering and residing in Japan each year, the establishment of a legal system by which munici- The Basic Resident Registration Law which currently does not apply to palities can provide basic public services to both foreign and Japanese foreign nationals will be revised, making it applicable to foreign nationals. residents has become an urgent concern. Consequently, foreign residents will be listed on the Basic Resident Registration along with Japanese residents. The Basic Resident Registration is the compiled residence records arranged by household. In order to address such concern, the law for partial amendments to the Basic Resident Registration Law was enacted at the 171st session of Diet and promulgated on July 15, 2009. This will make the Basic Resident Registration Law applicable to foreign residents and help improve their More convenient for foreign residents convenience and streamline municipalities’ operations. This amendment will come into effect within three years after the promulgation date (exact date is to be determined by the Cabinet). ◦This revision enables municipalities to have a better grasp of the members of multinational households (family composed of Japanese and non- In addition, the bill to abolish the Alien Registration Act and revise Japanese individuals), compared with the current two-tier system that list *concerned immigration laws was passed and enacted at the 171st Diet Japanese members and non-Japanese members of the same family in two session. -

Katsura Imperial Villa: the Photographs of Ishimoto Yasuhiro

Art in the Garden Katsura Imperial Villa: The Photographs of Ishimoto Yasuhiro Winter 2011 Katsura Imperial Villa: The Photographs of Ishimoto Yasuhiro This exhibition celebrates one of the most exquisite Harry Callahan and Aaron Siskind. He received the magnum opus 1955 exhibition titled The Family of THE MA OF MODERNISM: THE BOX architectural and garden treasures of Japan— Moholy-Nagy Prize awarded to top students of the Man at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. CONSTRUCTIONS OF DANIEL FAGERENG Katsura Imperial Villa in Kyoto—and one of its finest Institute for two consecutive years in 1951 and 1952. The box constructions of Daniel Fagereng were on living photographers, Ishimoto Yasuhiro, whose In 1966, Ishimoto returned again to Japan, where he view in conjunction with the Katsura photography 1953 images of Katsura introduced this unrivalled In 1953, Ishimoto returned to Japan to photograph became a professor at the Tokyo University of Art exhibition. The artist reinterprets the elements and masterpiece to the world. Katsura Detached Palace, and published the and Design. In 1969, he became a Japanese citizen. book, Katsura: Tradition and Creation in Japanese He visited Kyoto again in 1982, re-photographing components of traditional Japanese architecture in Born in San Francisco in 1921, and raised in Japan, Architecture, in 1960 with text by Walter Gropius Katsura in color to capture his own personal these mixed media constructions using light, line, Ishimoto returned to the U.S. at the age of 17 to and Tange Kenzo, two of the greatest architects of the vision of the richer, more complex character of and shadow as compositional elements. -

The Book of Tea

THE BOOK OF TEA KAKUZO OKAKURA ORIGINAL EDITION Prepared by JULIAN TAI Amazing-Green-Tea.com Sussex, United Kingdom Real Tea Directly from the Source www.amazing-green-tea.com Page 1 of 75 Steal This eBook! Well, okay, not quite. But actually, you now own, absolutely free, resale, reprint and redistribution rights to this ebook! This book currently sells at Amazon.com for at least $9.95! What does that really mean? It means that you can sell this ebook for any price you'd like and you keep 100% of the profits...or you can use it as a free bonus and give it away on your site... or you can print out as many copies as you want... or you can send it as a file to your friends and family who might be interested in reading it. It's your choice. Ebook Distribution The only restriction is that you cannot modify the ebook or its contents in any way. The entire ebook must be distributed in full. If you enjoy reading this ebook, please consider sharing it with others, so that they too can start discovering their next great tea! To tell a friend, click http://www.amazing-green-tea.com/share-this-site.html Real Tea Directly from the Source www.amazing-green-tea.com Page 2 of 75 Contents Chapter 1: The Cup of Humanity 4 Chapter 2: The School of Tea 14 Chapter 3: Taoism and Zennism 24 Chapter 4: The Tea Room 36 Chapter 5: Art Appreciation 49 Chapter 6: Flowers 58 Chapter 7: Tea Masters 70 About Amazing Green Tea 75 Real Tea Directly from the Source www.amazing-green-tea.com Page 3 of 75 Chapter 1: The Cup of Humanity Tea began as a medicine and grew into a beverage. -

Why an American Quaker Tutor for the Crown Prince? an Imperial Household's Strategy to Save Emperor Hirohito in Macarthur's

WHY AN AMERICAN QUAKER TUTOR FOR THE CROWN PRINCE? AN IMPERIAL HOUSEHOLD’S STRATEGY TO SAVE EMPEROR HIROHITO IN MACARTHUR’S JAPAN by Kaoru Hoshino B.A. in East Asian Studies, Wittenberg University, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts University of Pittsburgh 2010 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This thesis was presented by Kaoru Hoshino It was defended on April 2, 2010 and approved by Richard J. Smethurst, PhD, UCIS Research Professor, Department of History Akiko Hashimoto, PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Sociology Clark Van Doren Chilson, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Religious Studies Thesis Director: Richard J. Smethurst, PhD, UCIS Research Professor, Department of History ii Copyright © by Kaoru Hoshino 2010 iii WHY AN AMERICAN QUAKER TUTOR FOR THE CROWN PRINCE? AN IMPERIAL HOUSEHOLD’S STRATEGY TO SAVE EMPEROR HIROHITO IN MACARTHUR’S JAPAN Kaoru Hoshino, M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2010 This thesis examines the motives behind the Japanese imperial household’s decision to invite an American Christian woman, Elizabeth Gray Vining, to the court as tutor to Crown Prince Akihito about one year after the Allied Occupation of Japan began. In the past, the common narrative of scholars and the media has been that the new tutor, Vining, came to the imperial household at the invitation of Emperor Hirohito, who personally asked George Stoddard, head of the United States Education Mission to Japan, to find a tutor for the crown prince. While it may have been true that the emperor directly spoke to Stoddard regarding the need of a new tutor for the prince, the claim that the emperor came up with such a proposal entirely on his own is debatable given his lack of decision-making power, as well as the circumstances surrounding him and the imperial institution at the time of the Occupation. -

Manual De Iroha: Instalaci´On,Inicio, API, Gu´Iasy Resoluci´Onde Problemas Выпуск

Manual de Iroha: instalaci´on,inicio, API, gu´ıasy resoluci´onde problemas Выпуск Comunidad Iroha Hyperledger янв. 26, 2021 Содержание 1 Overview of Iroha 3 1.1 What are the key features of Iroha?................................3 1.2 Where can Iroha be used?......................................3 1.3 How is it different from Bitcoin or Ethereum?..........................3 1.4 How is it different from the rest of Hyperledger frameworks or other permissioned blockchains?4 1.5 How to create applications around Iroha?.............................4 2 С чего начать 5 2.1 Prerequisites.............................................5 2.2 Starting Iroha Node.........................................5 2.3 Try other guides...........................................7 3 Use Case Scenarios 9 3.1 Certificates in Education, Healthcare...............................9 3.2 Cross-Border Asset Transfers.................................... 10 3.3 Financial Applications........................................ 10 3.4 Identity Management........................................ 11 3.5 Supply Chain............................................. 11 3.6 Fund Management.......................................... 12 3.7 Related Research........................................... 12 4 Ключевые концепции 13 4.1 Sections................................................ 13 5 Guides and how-tos 23 5.1 Building Iroha............................................ 23 5.2 Конфигурация........................................... 29 5.3 Deploying Iroha.......................................... -

Hollywood Goes to Tokyo: American Cultural Expansion and Imperial Japan, 1918–1941

HOLLYWOOD GOES TO TOKYO: AMERICAN CULTURAL EXPANSION AND IMPERIAL JAPAN, 1918–1941 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Yuji Tosaka, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. Michael J. Hogan, Adviser Dr. Peter L. Hahn __________________________ Advisor Dr. Mansel G. Blackford Department of History ABSTRACT After World War I, the American film industry achieved international domi- nance and became a principal promoter of American cultural expansion, projecting images of America to the rest of the world. Japan was one of the few countries in which Hollywood lost its market control to the local industry, but its cultural exports were subjected to intense domestic debates over the meaning of Americanization. This dis- sertation examines the interplay of economics, culture, and power in U.S.-Japanese film trade before the Pacific War. Hollywood’s commercial expansion overseas was marked by internal disarray and weak industry-state relationships. Its vision of enlightened cooperation became doomed as American film companies hesitated to share information with one another and the U.S. government, while its trade association and local managers tended to see U.S. officials as potential rivals threatening their positions in foreign fields. The lack of cooperation also was a major trade problem in the Japanese film market. In general, American companies failed to defend or enhance their market position by joining forces with one another and cooperating with U.S. officials until they were forced to withdraw from Japan in December 1941. -

Scanned Using Book Scancenter 5022

The RUTGERS ART REVIEW Published Annually by the Students of the Graduate Program in Art History at Rutgers university Spring 1984 Volume V II Corporate Matching Funds Martin Eidclberg Carrier Corporation Foundation. Inc. Mrs. Helmut von Erffa Citicorp Dino Philip Galiano Seth A. Gopin Lifetime Benefactor Daria K. Gorman Henfield Foundation Mary C. Gray Nathaniel Gurien Benefactors Marion Husid In memory of Mary Bartlett Linda R. Idetberger Cowdrey Nancy M. KatzolT John and Katherine Kenfield Patrons Mr. and Mrs. Sanford Kirschenbaum In memory of Frank S. Allmuth, Julia M. Lappegaard Class of 1920 Cynthia and David Lawrence Mr. and Mrs. John L. Ayer Patricia I..eightcn Olga and Oev Berendsen Deborah Leuchovius Robert P. and Marcelle Bergman Marion and Allan Maiilin Dianne M. Green Ricky A. Malkin Frima and Larry Hofrichter Tod A. Marder Robert S. Peckar Joan Marter Paul S. Sheikewiiz, M.D. Thomas Mohle Jeffrey Wechsler Roberto A. Moya Scott E. Pringle Supporters Eliot Rowlands Carol and Jerry Alterman Anita Sagarese Randi Joan Alterman John M. Schwebke Richard Derr John Beldon Scott Archer St. Clair Harvey Mr. and Mrs. Eugene Seitz William E. Havemeyer Marie A. Somma Dr. Robert Kaita and Ms. Chiu-Tze Jack and Helga Spector Lin James H. Stubblebine Mr. and Mrs. Edward J. Linky Richard and Miriam Wallman Mr. and Mrs. James McLachlan Harvey and Judith Waterman Barbara and Howard Mitnick Michael F. Weber Elizabeth M. Thompson Sarah B. Wilk Lorraine Zito*Durand Friends Department of Art History, University of Ann Conover, Inc. Delaware Keith Asszony The Pennsylvania State University, Renee and Matthew Baigell Department of Art History William and Elizabeth Bauer The Graduate School-New Brunswick, Naomi Boretz Rutgers University Phillip Dennis Cate Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum Zeau C. -

The Making of Modern Japan

The Making of Modern Japan The MAKING of MODERN JAPAN Marius B. Jansen the belknap press of harvard university press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Copyright © 2000 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Third printing, 2002 First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2002 Book design by Marianne Perlak Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jansen, Marius B. The making of modern Japan / Marius B. Jansen. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-674-00334-9 (cloth) isbn 0-674-00991-6 (pbk.) 1. Japan—History—Tokugawa period, 1600–1868. 2. Japan—History—Meiji period, 1868– I. Title. ds871.j35 2000 952′.025—dc21 00-041352 CONTENTS Preface xiii Acknowledgments xvii Note on Names and Romanization xviii 1. SEKIGAHARA 1 1. The Sengoku Background 2 2. The New Sengoku Daimyo 8 3. The Unifiers: Oda Nobunaga 11 4. Toyotomi Hideyoshi 17 5. Azuchi-Momoyama Culture 24 6. The Spoils of Sekigahara: Tokugawa Ieyasu 29 2. THE TOKUGAWA STATE 32 1. Taking Control 33 2. Ranking the Daimyo 37 3. The Structure of the Tokugawa Bakufu 43 4. The Domains (han) 49 5. Center and Periphery: Bakufu-Han Relations 54 6. The Tokugawa “State” 60 3. FOREIGN RELATIONS 63 1. The Setting 64 2. Relations with Korea 68 3. The Countries of the West 72 4. To the Seclusion Decrees 75 5. The Dutch at Nagasaki 80 6. Relations with China 85 7. The Question of the “Closed Country” 91 vi Contents 4. STATUS GROUPS 96 1. The Imperial Court 97 2.